The Ballad of Larachmhor

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Liturgical Services in the Parish

RC Diocese Argyll & Isles – Arisaig & Morar Missions: Parish Services __________________________________________ Charity Reg. No. SC002876. BIRTHDAY: Lisa MacDonald 01.02 ............................................................ Ad multos annos! st th ® Weekday Services (1 February – 6 February) Catholic Rough Bounds Video Streamed Mass on Parish Facebook. Public Masses: You need to book your attendance on Sunday in advance! Weekday: you have to leave your contact details at the door Parish newsletter Monday ..................................................................................................................................... Morar, 10am www.catholicroughbounds.org Requiem Mass of Christina MacPherson RIP FACEBOOK.COM/CATHOLICROUGHBOUNDS Tuesday The Presentation of the Lord ....................................................................................... Arisaig, 10am Requiem Mass of Theresa MacKenzie RIP Parish of St. Mary’s, Arisaig & St. Donnan’s, Isle of Eigg Wednesday ............................................................................................................................... Morar, 10am Eilidh MacDonald – Birthday Mass Parish of Our Lady of Perpetual Succour & St Cumin’s, Morar Thursday St Thomas Aquinas .................................................................................................... Arisaig, 10am St. Patrick’s, Mallaig & St. Columba’s, Isle of Canna Isabel MacDonald RIP Friday ....................................................................................................................................... -

FORT WILLIAM to MALLAIG Experience the Breathtaking Beauty of the Scottish Western Highlands Aboard the World-Famous Jacobite Steam Train and Its Vintage Carriages

West Coast Railways Presents FAMOUS STEAM TRAIN 2021 Season FORT WILLIAM TO MALLAIG Experience the breathtaking beauty of the Scottish Western Highlands aboard the World-famous Jacobite Steam Train and its vintage carriages. “The World’s Greatest Railway Journey” THE JOURNEY Fort William to Mallaig Described as the greatest railway journey in the world, this 84 mile round trip takes you past a list of impressive extremes. Starting at the highest mountain in Britain, Ben Nevis, it visits Britain’s most westerly mainland railway station, Arisaig; passes close by the deepest freshwater loch in Britain, Loch Morar and the shortest river in Britain, River Morar, finally arriving next to the deepest seawater loch in Europe, Loch Nevis! The Train stops en route to Mallaig at the village of Glenfinnan. Beyond Glenfinnan are the beautiful villages of Lochailort, Arisaig, Morar and Mallaig. You may alight at Arisaig by request to the guard. From here, on a clear summer’s day, you can see the “Small Isles” of Rum, Eigg, Muck, Canna and the southern tip of Skye. The train continues on from here passing Morar and the silvery beaches used in the films “Highlander” and “Local Hero”. Come and join us and find out why! THE ROAD TO THE ISLES Following Harry Potter.... West Coast Railways, operators of ‘The Jacobite,’ provided the steam engine and carriages for the ‘Hogwarts Express’ as seen in ‘Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone’ and others in this wonderful series of films. Some of the carriages of ‘The Jacobite’ are similar to those used in the ‘Harry Potter’ films. -

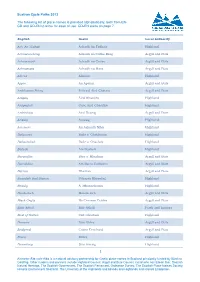

Sustran Cycle Paths 2013

Sustran Cycle Paths 2013 The following list of place-names is provided alphabetically, both from EN- GD and GD-EN to allow for ease of use. GD-EN starts on page 7. English Gaelic Local Authority Ach' An Todhair Achadh An Todhair Highland Achnacreebeag Achadh na Crithe Beag Argyll and Bute Achnacroish Achadh na Croise Argyll and Bute Achnamara Achadh na Mara Argyll and Bute Alness Alanais Highland Appin An Apainn Argyll and Bute Ardchattan Priory Priòraid Àird Chatain Argyll and Bute Ardgay Àird Ghaoithe Highland Ardgayhill Cnoc Àird Ghaoithe Highland Ardrishaig Àird Driseig Argyll and Bute Arisaig Àrasaig Highland Aviemore An Aghaidh Mhòr Highland Balgowan Baile a' Ghobhainn Highland Ballachulish Baile a' Chaolais Highland Balloch Am Bealach Highland Baravullin Bàrr a' Mhuilinn Argyll and Bute Barcaldine Am Barra Calltainn Argyll and Bute Barran Bharran Argyll and Bute Beasdale Rail Station Stèisean Bhiasdail Highland Beauly A' Mhanachainn Highland Benderloch Meadarloch Argyll and Bute Black Crofts Na Croitean Dubha Argyll and Bute Blair Atholl Blàr Athall Perth and kinross Boat of Garten Coit Ghartain Highland Bonawe Bun Obha Argyll and Bute Bridgend Ceann Drochaid Argyll and Bute Brora Brùra Highland Bunarkaig Bun Airceig Highland 1 Ainmean-Àite na h-Alba is a national advisory partnership for Gaelic place-names in Scotland principally funded by Bòrd na Gaidhlig. Other funders and partners include Highland Council, Argyll and Bute Council, Comhairle nan Eilean Siar, Scottish Natural Heritage, The Scottish Government, The Scottish Parliament, Ordnance Survey, The Scottish Place-Names Society, Historic Environment Scotland, The University of the Highlands and Islands and Highlands and Islands Enterprise. -

Kinneddar Lodges, Back of Keppoch

KINNEDDAR LODGES, BACK OF KEPPOCH £195,000 (GUIDE PRICE) Kinneddar Lodges are a collection of three well-presented holiday cottages: Loch Lomond, Loch Ness and Loch Morar. The lodges are located on a private site and situated at the Back of Keppoch, Arisaig. The site enjoys sea views towards Skye and close to local amenities in Arisaig and Mallaig. Property Summary Kinneddar Lodges boast a number of features such as:- • Exceptional sea views towards Skye • Ideal lifestyle / business opportunity • Private setting • Fort William (34 miles); Glasgow (142 miles) In addition to the lodges there is a storage shed. In all, the site extends to 0.34 acres (0.138 hectares) For Sale As a Whole KINNEDDAR LODGES BACK OF KEPPOCH ARISAIG, PH39 4NS £195,000 (GUIDE PRICE) Situation Accommodation Located close to Arisaig, a popular village on the West Coast Loch Morar of Scotland along the famous Road to the Isles. The Road • Open plan Kitchen, Dining and Living Room. to the Isles links Fort William and Mallaig (situated 35 and • One Double Bedroom. 8 miles from the site respectively). From Mallaig, there is a • One Twin Bedroom LIVING AREA BATHROOM BEDROOM daily ferry on to the Small Isles, Isle of Skye and the Knoydart • Showeroom with WC Peninsula. Kinneddar Lodges offer an ideal lifestyle Sunroom opportunity, being well placed for those looking to enjoy • living on the West Coast, an area renowned for outdoor Loch Ness and Loch Lomond activities such as walking, fishing, sailing, cycling, climbing • Open plan Kitchen, Dining and Living Room. - and all in stunning scenery that allows one to enjoy the • One Double Bedroom. -

Strategic Housing Investment Plan

Agenda 7 Item Report LA/5/21 No HIGHLAND COUNCIL Committee: Lochaber Committee Date: 18 January 2021 Report Title: Strategic Housing Investment Plan Report By: Executive Chief Officer - Infrastructure and Environment 1. PURPOSE/EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1.1 This report invites consideration of the Highland’s draft Strategic Housing Investment Plan (SHIP), which sets out proposals for affordable housing investment during 2021–2026, as reported to Economy and Infrastructure Committee at the meeting held on 4 November 2020. 1.2 The report also updates members on the 2020/21 affordable housing programme within Lochaber. 2. RECOMMENDATIONS 2.1 Members are asked to: • consider the Highland’s draft Strategic Housing Investment Plan and provide comments for further consideration by Economy and Infrastructure Committee; and • note the progress within the developments highlighted within section 5 of this report and included as appendix 1 of the report. 3. IMPLICATIONS 3.1 Resource - The Council House Build proposals contained within SHIP will be progressed in line with the current agreed funding mechanisms of the Scottish Government Grant, City Region Deal investment, Landbank subsidy and Prudential Borrowing. 3.2 Legal - no significant legal issues. 3.3 Community (Equality, Poverty and Rural) - This report will assist in the delivery of affordable housing in rural areas. 3.4 Climate Change/Carbon Clever – Neutral impact. 3.5 Risk - Normal development risks on individual projects 3.6 Gaelic - No impact. 4. BACKGROUND 4.1 Strategic Housing Investment Plans (SHIPs) are developed in line with Scottish Government guidance which sets a submission date of mid-December 20. The draft SHIP was agreed by E&I Committee at the meeting held on 4 November 2020 on the basis that there would be consideration of any subsequent comments received from Area Committees. -

505 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

505 bus time schedule & line map 505 Lochailort View In Website Mode The 505 bus line (Lochailort) has 2 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Lochailort: 7:10 AM (2) Mallaig: 5:40 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 505 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 505 bus arriving. Direction: Lochailort 505 bus Time Schedule 14 stops Lochailort Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday Not Operational Monday 7:10 AM King's Way, Mallaig U5364, Scotland Tuesday 7:10 AM Ard Mhor, Mallaig Wednesday 7:10 AM Blaven View, Scotland Thursday 7:10 AM Fire Station, Mallaig Friday 7:10 AM Loch Nevis Terrace, Scotland Saturday Not Operational Cameron Avenue, Mallaig Boatyard, Mallaig East Bay, Scotland 505 bus Info High School, Mallaig Direction: Lochailort Stops: 14 Primary School, Morar Trip Duration: 39 min Columba Road, Scotland Line Summary: King's Way, Mallaig, Ard Mhor, Mallaig, Fire Station, Mallaig, Cameron Avenue, Station, Morar Mallaig, Boatyard, Mallaig, High School, Mallaig, Primary School, Morar, Station, Morar, Primary Primary School, Arisaig School, Arisaig, Post O∆ce, Arisaig, Clanranald Place, Arisaig, Road End, Arisaig, Station, Beasdale, Post O∆ce, Arisaig Hotel, Lochailort Clanranald Place, Arisaig B8008, Scotland Road End, Arisaig Station, Beasdale Hotel, Lochailort Direction: Mallaig 505 bus Time Schedule 41 stops Mallaig Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday Not Operational Monday 5:40 PM Fort William Bus Station, Fort William Macfarlane Way, Fort William Tuesday 5:40 PM Leisure Centre, -

A'chleit (Argyll), A' Chleit

Iain Mac an Tàilleir 2003 1 A'Chleit (Argyll), A' Chleit. "The mouth of the Lednock", an obscure "The cliff or rock", from Norse. name. Abban (Inverness), An t-Àban. Aberlemno (Angus), Obar Leamhnach. “The backwater” or “small stream”. "The mouth of the elm stream". Abbey St Bathans (Berwick). Aberlour (Banff), Obar Lobhair. "The abbey of Baoithean". The surname "The mouth of the noisy or talkative stream". MacGylboythin, "son of the devotee of Aberlour Church and parish respectively are Baoithean", appeared in Dumfries in the 13th Cill Drostain and Sgìre Dhrostain, "the century, but has since died out. church and parish of Drostan". Abbotsinch (Renfrew). Abernethy (Inverness, Perth), Obar Neithich. "The abbot's meadow", from English/Gaelic, "The mouth of the Nethy", a river name on lands once belonging to Paisley Abbey. suggesting cleanliness. Aberarder (Inverness), Obar Àrdair. Aberscross (Sutherland), Abarsgaig. "The mouth of the Arder", from àrd and "Muddy strip of land". dobhar. Abersky (Inverness), Abairsgigh. Aberargie (Perth), Obar Fhargaidh. "Muddy place". "The mouth of the angry river", from fearg. Abertarff (Inverness), Obar Thairbh. Aberbothrie (Perth). "The mouth of the bull river". Rivers and "The mouth of the deaf stream", from bodhar, stream were often named after animals. “deaf”, suggesting a silent stream. Aberuchill (Perth), Obar Rùchaill. Abercairney (Perth). Although local Gaelic speakers understood "The mouth of the Cairney", a river name this name to mean "mouth of the red flood", from càrnach, meaning “stony”. from Obar Ruadh Thuil, older evidence Aberchalder (Inverness), Obar Chaladair. points to this name containing coille, "The mouth of the hard water", from caled "wood", with similarities to Orchill. -

West Highland and Islands LDP Examination

Planning and Environmental Appeals Division Telephone: 01324 696455 Fax: 01324 696444 E-mail: [email protected] Mr T Stott Highland Council Sent By E-mail Our ref: LDP-270-6 10 May 2019 Dear Mr Stott PROPOSED WEST HIGHLAND AND ISLANDS LOCAL DEVELOPMENT PLAN THE TOWN AND COUNTRY PLANNING (DEVELOPMENT PLANNING) (SCOTLAND) REGULATIONS 2008 SUBMISSION OF THE REPORT OF THE EXAMINATION We refer to our appointment by the Scottish Ministers to conduct the examination of the above proposed plan. Having satisfied ourselves that the planning authority’s consultation and engagement exercises conformed with their participation statement, our examination of the proposed plan commenced on 7 August 2018. We have completed the examination and now submit our report. In our examination, we considered all 28 issues arising from unresolved representations identified by yourselves to the Proposed Local Development Plan. In each case we have taken account of the original representations, as well as your summaries of the representations and your responses to such, and we have set out our conclusions and recommendations in relation to each issue in our report. We undertook a comprehensive series of unaccompanied site inspections. In addition we made six further information requests from the council and representees and the responses to these have been taken into account in making our findings. We did not require to hold any hearing or inquiry sessions. Strategic environmental assessment We have reviewed the environmental report which accompanies the proposed plan. This provides an assessment of the vision and spatial strategy and policies including alternative approaches as well as an assessment of site allocations and alternative sites. -

The Eastern Post, 1868-1870 Compiled by Detlev Mares, Institute of History, Darmstadt University of Technology

Notes from: The Eastern Post, 1868-1870 compiled by Detlev Mares, Institute of History, Darmstadt University of Technology (published on Saturday) 1868-10-18: EP 001 Election Addresses by E. Beales, Samuda, H. Labouchere, Ayrton, John Holms, etc. <Kopie> 1868-10-18: EP 001 Election Intelligence Tower Hamlets: proposed coalition between Beales and Ayrton; meeting by Beales, Davis in chair; Newton not withdrawing his candidature, wants working men to be represented; Hackney: Lieut.-Colonel Dickson gets support of Irish Reform League; canvas by Samuda; Chelsea: meeting with Odger, Lloyd Jones in chair; meeting with Dilke, T. Stedman in chair; Sheffield: address by Roebuck; Southampton: Russell Gurney and P. M. Hoare; Wolverhampton: address by C. Pl Villiers; Nottingham: address by Bernal Osborne on the other Liberal candidates: Rev. Peter Clayden, Merriman ("was one of the most able and disinterested lawyers in London, and a disinterested lawyer was a great curiosity - ... have to attend to his business first and his working men afterwards"), Seely; Osborne himself in difference from Seely "not a large employer of labour", but "a farmer on a small scale"; Frome: resolution of thanks by Thomas Hughes MP for the outgoing MP Rawlinson <Kopie> 1868-10-18: EP 004 (Commentary) Flag-Rant on Conservatism <Kopie> 1868-10-18: EP 004 (Commentary) Mr. Gladstone <Kopie> 2 1868-10-18: EP 004 (Commentary) The Middlesex Election on Henry Labouchere <Kopie> 1868-10-18: EP 004 (Commentary) To Our Readers on Irish Church <Kopie> 1868-10-18: EP 004 The Revolution in Spain <Kopie> 1868-10-18: EP 006 Mr. Gladstone at Warrington election speeches by Gladstone and H. -

Winter 2016 Newsletter

WINTER 2016 NEW AFFORDABLE HOMES IN LOCHABER The Association is delighted that our Development programme has begun to pay dividends for the people of Lochaber. During the summer, 3 homes for affordable social rent were completed in Kilchoan with families moving in at the end of August. The homes were designed by Fort William architects,Kearney Donald Partnership, and built at a cost of £381,865 by S&K MacDonald Homes Ltd. Curlew Place in Lochyside, slightly later than anticipated, welcomed its new residents, on 21st November 2016. This new development consists of 8 homes for affordable social rent and 2 homes available to buy under the LIFT shared equity scheme and was built at a cost of just over £1 million. These homes were designed by D. Kelly Design of Fort William and constructed by Spean Bridge contractor, R.E.Campbell Joinery Ltd. Funding for both of these projects came from the Scottish Government and Lochaber Housing Association with private finance provided by Charities Aid Foundation (CAF) Bank PLEASE NOTE To welcome our new tenants the Association placed all the Our offices will be addresses for the 2 developments closed on Friday 23rd into a draw and selected a home in December at 4.00pm each development. The winning and re-open on recipients were then presented with Thursday 5th January a hamper. at 10am. Pictured to the left are Mr & Mrs To report an Frame from Canach Cottages, emergency repair Kilchoan and pictured above is Mrs Telephone J Smissen-Smith from Curlew Place in Lochyside, receiving their hampers from Irene Cameron their 0845 038 0027 Housing Officer. -

Arisaig: Morar Sands HL 005 204 16 December 2009

Scottish Sanitary Survey Project Restricted Sanitary Survey Report Arisaig: Morar Sands HL 005 204 16 December 2009 Cefas SSS R0803 Final 211209 Report Distribution – Arisaig: Morar Sands Date Name Agency* Linda Galbraith Scottish Government Judith White Scottish Government Ewan Gillespie SEPA Douglas Sinclair SEPA Stephan Walker Scottish Water Alex Adrian Crown Estate Alan Yates Highland Council Stephen Lewis OC sampling officer John Grieve Harvester** (Loch Leven Shellfish) * Distribution of both draft and final reports to relevant agency personnel is undertaken by FSAS. ** Distribution of draft and final reports to harvesters in undertaken by the relevant local authority. i Cefas SSS R0803 Final 211209 Acknowledgements We are thankful to the following persons and agencies who provided assistance and information used in the following report: Highland Council - Lochaber John Grieve, Loch Leven Shellfish Rob Grieve, Loch Leven Shellfish James Malarkey, Loch Leven Shellfish SEPA Registry Office Dingwall Scottish Water Dr. Alan Lilly, Macaulay Land Research Institute ii Cefas SSS R0803 Final 211209 Table of Contents 1. Area Overview ................................................................................................. 1 1.1 Land Cover ............................................................................................... 2 1.2 Human Population .................................................................................... 2 2. Fishery............................................................................................................ -

Bee-Hive“, 1864-1876 Compiled by Detlev Mares, Institute of History, Darmstadt University of Technology

1 Index to the „Bee-Hive“, 1864-1876 compiled by Detlev Mares, Institute of History, Darmstadt University of Technology 1864-04-23: BH 001 Garibaldi's Forced Departure from England <Kopie> 1864-04-23: BH 001 many reports on Garibaldi-Visit <Kopie> 1864-04-23: BH 001 National Reform Conference <Kopie> 1864-04-23: BH 001 Working Men's Shakespeare Celebration <Kopie> 1864-06-04: BH 001 Public meetings in the Parks letter by Beales on right of public meeting 1864-06-04: BH 001 The Trades Newspaper Company (Limited) annual report by Potter, clash with Odger; Medland (painter), Mildred (carpenter), Wright, Vize, Dell, Connolly, Shaw, Dunning, Garland, Odger, Margrath, Troup, Graham, Battenbury, Hancock, Murray 1864-06-11: BH 001 Metropolitan Trades' Hall meeting at rooms of Universal League, 18 Greek Street, of friendly, trades, co-op, and working men's clubs delegates; rooms let gratuitously for the purpose to establish Central Working Men's Hall in London; 2 plans: Hartwell (ed. BH): for company under Limited Liability Act H. Solly: for company registered under Industrial Societies Act Weston (Joiner) chair, Odgers, Trimlett (Friends of Freedom Society of Carpenters), Hammett (City Ladies' Shoemakers), Edgar (St. James Co-operative Society) 1864-06-11: BH 001 Summary of the Week. Domestic ... Beales has prepared a legal paper proving right of people to meet in public parks, read to Right of Public Meeting Defence Cttee 1864-06-25: BH 001 General Garibaldi <Kopie> 2 1864-06-25: BH 001 Hearts of Oak Reform Movement W. Allen, sec. of the reform movement, in chair 1864-06-25: BH 001 Manhood Suffrage.