ISO/IEC JTC1/SC2/WG2 N3194 L2/06-Xxx

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Unicode Request for Cyrillic Modifier Letters Superscript Modifiers

Unicode request for Cyrillic modifier letters L2/21-107 Kirk Miller, [email protected] 2021 June 07 This is a request for spacing superscript and subscript Cyrillic characters. It has been favorably reviewed by Sebastian Kempgen (University of Bamberg) and others at the Commission for Computer Supported Processing of Medieval Slavonic Manuscripts and Early Printed Books. Cyrillic-based phonetic transcription uses superscript modifier letters in a manner analogous to the IPA. This convention is widespread, found in both academic publication and standard dictionaries. Transcription of pronunciations into Cyrillic is the norm for monolingual dictionaries, and Cyrillic rather than IPA is often found in linguistic descriptions as well, as seen in the illustrations below for Slavic dialectology, Yugur (Yellow Uyghur) and Evenki. The Great Russian Encyclopedia states that Cyrillic notation is more common in Russian studies than is IPA (‘Transkripcija’, Bol’šaja rossijskaja ènciplopedija, Russian Ministry of Culture, 2005–2019). Unicode currently encodes only three modifier Cyrillic letters: U+A69C ⟨ꚜ⟩ and U+A69D ⟨ꚝ⟩, intended for descriptions of Baltic languages in Latin script but ubiquitous for Slavic languages in Cyrillic script, and U+1D78 ⟨ᵸ⟩, used for nasalized vowels, for example in descriptions of Chechen. The requested spacing modifier letters cannot be substituted by the encoded combining diacritics because (a) some authors contrast them, and (b) they themselves need to be able to take combining diacritics, including diacritics that go under the modifier letter, as in ⟨ᶟ̭̈⟩BA . (See next section and e.g. Figure 18. ) In addition, some linguists make a distinction between spacing superscript letters, used for phonetic detail as in the IPA tradition, and spacing subscript letters, used to denote phonological concepts such as archiphonemes. -

+1. Introduction 2. Cyrillic Letter Rumanian Yn

MAIN.HTM 10/13/2006 06:42 PM +1. INTRODUCTION These are comments to "Additional Cyrillic Characters In Unicode: A Preliminary Proposal". I'm examining each section of that document, as well as adding some extra notes (marked "+" in titles). Below I use standard Russian Cyrillic characters; please be sure that you have appropriate fonts installed. If everything is OK, the following two lines must look similarly (encoding CP-1251): (sample Cyrillic letters) АабВЕеЗКкМНОопРрСсТуХхЧЬ (Latin letters and digits) Aa6BEe3KkMHOonPpCcTyXx4b 2. CYRILLIC LETTER RUMANIAN YN In the late Cyrillic semi-uncial Rumanian/Moldavian editions, the shape of YN was very similar to inverted PSI, see the following sample from the Ноул Тестамент (New Testament) of 1818, Neamt/Нямец, folio 542 v.: file:///Users/everson/Documents/Eudora%20Folder/Attachments%20Folder/Addons/MAIN.HTM Page 1 of 28 MAIN.HTM 10/13/2006 06:42 PM Here you can see YN and PSI in both upper- and lowercase forms. Note that the upper part of YN is not a sharp arrowhead, but something horizontally cut even with kind of serif (in the uppercase form). Thus, the shape of the letter in modern-style fonts (like Times or Arial) may look somewhat similar to Cyrillic "Л"/"л" with the central vertical stem looking like in lowercase "ф" drawn from the middle of upper horizontal line downwards, with regular serif at the bottom (horizontal, not slanted): Compare also with the proposed shape of PSI (Section 36). 3. CYRILLIC LETTER IOTIFIED A file:///Users/everson/Documents/Eudora%20Folder/Attachments%20Folder/Addons/MAIN.HTM Page 2 of 28 MAIN.HTM 10/13/2006 06:42 PM I support the idea that "IA" must be separated from "Я". -

Coc Man Obin Oyubu Iyii Akinaglobal Oncology,THE MEME, Kede Botswana Oncology Global Outreach (BOTSOGO). © 11/2017 Global Onco

CarolynTaylor: Global Focus on Cancer Global Focus CarolynTaylor: CANCA KEDE YIN Coc man obin oyubu iyii akinaGlobal Oncology,THE MEME, kede Botswana Oncology Global Outreach (BOTSOGO). © 11/2017 Global Oncology, Inc. All Rights Reserved. APENY IKOM TWO KANCA APENY AME ITWERO BEDO KEDE Buk man miyi ingeyo ngo amyero igen ka itye kede two kanca kede kaa itye inwongo yat ame lyenyo ikom two kanca onyo mac ame neko kudi me kanca. » Kanca obedo ngo? » Kwon kanca apapat obedo mene nie? Kanca obedo two ame miyo jami onyo kudi Kanca ame makako awang mac, kanca me del aber me komi dongo oyot oyot akati kit ame kom, kanca me remo ducu obedo kwon kanca. myero dong kede, ka pe inwongo kony me yat onyo mac ame neko gii oko romo miyi nwongo goro adwong tiutwal me kom. » Bedo inget jo ame tye kede kanca romo miyi peko? Eyo, bedo inget dano onyo jo ame tye kede » Ibino nwongo yat awene? kanca pe kede peko moro. Kanca pe obedo two Dakatali bino miyi ngeyo awene ame ibino ame kobo onyo onwongoikom dano ame tye mito cako yat me ckanca iye. ilanget wa. Pwod iromo rwate kede dako onyo icoo ame tye kede kanca ibutu ento tii kede opira me gengo yin nwongo kwo okene acalo two jonyo. Apeny piri: CANCA KEDE YIN 1 © 11/2017 Global Oncology, Inc. All Rights Reserved APENY IKOM YAT ME KANCA IV yat me kanca Yat kanca me amwonya mwonya » Yat me kanca obeo yat ango? » Onyo yat me kanca dang tye kede peki ame kelo ka icako tic kede? Man obedo yat ame otiyo kede me cango nyo dwoko ping kero atwo kanca. -

(English-Kreyol Dictionary). Educa Vision Inc., 7130

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 401 713 FL 023 664 AUTHOR Vilsaint, Fequiere TITLE Diksyone Angle Kreyol (English-Kreyol Dictionary). PUB DATE 91 NOTE 294p. AVAILABLE FROM Educa Vision Inc., 7130 Cove Place, Temple Terrace, FL 33617. PUB TYPE Reference Materials Vocabularies /Classifications /Dictionaries (134) LANGUAGE English; Haitian Creole EDRS PRICE MFO1 /PC12 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Alphabets; Comparative Analysis; English; *Haitian Creole; *Phoneme Grapheme Correspondence; *Pronunciation; Uncommonly Taught Languages; *Vocabulary IDENTIFIERS *Bilingual Dictionaries ABSTRACT The English-to-Haitian Creole (HC) dictionary defines about 10,000 English words in common usage, and was intended to help improve communication between HC native speakers and the English-speaking community. An introduction, in both English and HC, details the origins and sources for the dictionary. Two additional preliminary sections provide information on HC phonetics and the alphabet and notes on pronunciation. The dictionary entries are arranged alphabetically. (MSE) *********************************************************************** Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made from the original document. *********************************************************************** DIKSIONt 7f-ngigxrzyd Vilsaint tick VISION U.S. DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION Office of Educational Research and Improvement EDU ATIONAL RESOURCES INFORMATION "PERMISSION TO REPRODUCE THIS CENTER (ERIC) MATERIAL HAS BEEN GRANTED BY This document has been reproduced as received from the person or organization originating it. \hkavt Minor changes have been made to improve reproduction quality. BEST COPY AVAILABLE Points of view or opinions stated in this document do not necessarily represent TO THE EDUCATIONAL RESOURCES official OERI position or policy. INFORMATION CENTER (ERIC)." 2 DIKSYCAlik 74)25fg _wczyd Vilsaint EDW. 'VDRON Diksyone Angle-Kreyal F. Vilsaint 1992 2 Copyright e 1991 by Fequiere Vilsaint All rights reserved. -

Old Cyrillic in Unicode*

Old Cyrillic in Unicode* Ivan A Derzhanski Institute for Mathematics and Computer Science, Bulgarian Academy of Sciences [email protected] The current version of the Unicode Standard acknowledges the existence of a pre- modern version of the Cyrillic script, but its support thereof is limited to assigning code points to several obsolete letters. Meanwhile mediæval Cyrillic manuscripts and some early printed books feature a plethora of letter shapes, ligatures, diacritic and punctuation marks that want proper representation. (In addition, contemporary editions of mediæval texts employ a variety of annotation signs.) As generally with scripts that predate printing, an obvious problem is the abundance of functional, chronological, regional and decorative variant shapes, the precise details of whose distribution are often unknown. The present contents of the block will need to be interpreted with Old Cyrillic in mind, and decisions to be made as to which remaining characters should be implemented via Unicode’s mechanism of variation selection, as ligatures in the typeface, or as code points in the Private space or the standard Cyrillic block. I discuss the initial stage of this work. The Unicode Standard (Unicode 4.0.1) makes a controversial statement: The historical form of the Cyrillic alphabet is treated as a font style variation of modern Cyrillic because the historical forms are relatively close to the modern appearance, and because some of them are still in modern use in languages other than Russian (for example, U+0406 “I” CYRILLIC CAPITAL LETTER I is used in modern Ukrainian and Byelorussian). Some of the letters in this range were used in modern typefaces in Russian and Bulgarian. -

1. Introduction

ISO/IEC JTC1/SC2/WG2 N4162 Universal Multiple-Octet Coded Character Set International Organization for Standardization Organisation Internationale de Normalisation Международная организация по стандартизации Doc Type: Working Group Document Title: Revised proposal to encode Latin letters used in the Former Soviet Union Authors: Nurlan Joomagueldinov, Karl Pentzlin, Ilya Yevlampiev Status: Expert Contribution Action: For consideration by JTC1/SC2/WG2 and UTC Date: 2012-01-29 Supersedes: L2/11-360, WG2 N4162 – Two characters were added for Komi-Permyak (LATIN CAPITAL/SMALL LETTER ZE WITH DESCENDER). – The LATIN SMALL LETTER CAUCASIAN LONG S was disunified from U+017F LATIN SMALL LETTER LONG S (see the remark in the list of proposed characters at U+AB89). – Some issues raised in L2/11-422 are addressed in the text (especially, section 2.1.1 "Descender vs. cedilla" was added). Terminology used in this document: "Descender" refers to the specially formed appendage on letters like the one in the already encoded letter U+A790 LATIN CAPITAL LETTER N WITH DESCENDER. "Typographical descender" refers to the part of a letter below the baseline, thus resembling the term "descender" as used in typography. 1. Introduction In the wake of the October Revolution of 1917 in Russia, alphabetization of the people living in the then formed Soviet Union became an important point of the political agenda. At that time, some languages spoken in the Soviet Union had no standardized orthography at all, while others (especially in areas where the Islam was the predominant religion) used the Arabic script. As most of these orthographies did not reflect the phonetics of these languages very well, and as the Arabic script was considered unnecessarily difficult by some due to its structure, for most of the non-Slavic languages it was decided to design new orthographies from scratch. -

5892 Cisco Category: Standards Track August 2010 ISSN: 2070-1721

Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF) P. Faltstrom, Ed. Request for Comments: 5892 Cisco Category: Standards Track August 2010 ISSN: 2070-1721 The Unicode Code Points and Internationalized Domain Names for Applications (IDNA) Abstract This document specifies rules for deciding whether a code point, considered in isolation or in context, is a candidate for inclusion in an Internationalized Domain Name (IDN). It is part of the specification of Internationalizing Domain Names in Applications 2008 (IDNA2008). Status of This Memo This is an Internet Standards Track document. This document is a product of the Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF). It represents the consensus of the IETF community. It has received public review and has been approved for publication by the Internet Engineering Steering Group (IESG). Further information on Internet Standards is available in Section 2 of RFC 5741. Information about the current status of this document, any errata, and how to provide feedback on it may be obtained at http://www.rfc-editor.org/info/rfc5892. Copyright Notice Copyright (c) 2010 IETF Trust and the persons identified as the document authors. All rights reserved. This document is subject to BCP 78 and the IETF Trust's Legal Provisions Relating to IETF Documents (http://trustee.ietf.org/license-info) in effect on the date of publication of this document. Please review these documents carefully, as they describe your rights and restrictions with respect to this document. Code Components extracted from this document must include Simplified BSD License text as described in Section 4.e of the Trust Legal Provisions and are provided without warranty as described in the Simplified BSD License. -

Kyrillische Schrift Für Den Computer

Hanna-Chris Gast Kyrillische Schrift für den Computer Benennung der Buchstaben, Vergleich der Transkriptionen in Bibliotheken und Standesämtern, Auflistung der Unicodes sowie Tastaturbelegung für Windows XP Inhalt Seite Vorwort ................................................................................................................................................ 2 1 Kyrillische Schriftzeichen mit Benennung................................................................................... 3 1.1 Die Buchstaben im Russischen mit Schreibschrift und Aussprache.................................. 3 1.2 Kyrillische Schriftzeichen anderer slawischer Sprachen.................................................... 9 1.3 Veraltete kyrillische Schriftzeichen .................................................................................... 10 1.4 Die gebräuchlichen Sonderzeichen ..................................................................................... 11 2 Transliterationen und Transkriptionen (Umschriften) .......................................................... 13 2.1 Begriffe zum Thema Transkription/Transliteration/Umschrift ...................................... 13 2.2 Normen und Vorschriften für Bibliotheken und Standesämter....................................... 15 2.3 Tabellarische Übersicht der Umschriften aus dem Russischen ....................................... 21 2.4 Transliterationen veralteter kyrillischer Buchstaben ....................................................... 25 2.5 Transliterationen bei anderen slawischen -

AIX Globalization

AIX Version 7.1 AIX globalization IBM Note Before using this information and the product it supports, read the information in “Notices” on page 233 . This edition applies to AIX Version 7.1 and to all subsequent releases and modifications until otherwise indicated in new editions. © Copyright International Business Machines Corporation 2010, 2018. US Government Users Restricted Rights – Use, duplication or disclosure restricted by GSA ADP Schedule Contract with IBM Corp. Contents About this document............................................................................................vii Highlighting.................................................................................................................................................vii Case-sensitivity in AIX................................................................................................................................vii ISO 9000.....................................................................................................................................................vii AIX globalization...................................................................................................1 What's new...................................................................................................................................................1 Separation of messages from programs..................................................................................................... 1 Conversion between code sets............................................................................................................. -

Universal Multiple-Octet Coded Character Set (UCS) —

ISO/IEC JTC1 SC2/WG2 N2845 all Final Proposed Draft Amendment (FPDAM) 1 ISO/IEC 10646:2003/Amd.1:2004 (E) Information technology — Universal Multiple-Octet Coded Character Set (UCS) — AMENDMENT 1: Glagolitic, Coptic, Georgian and other characters In the definition of Graphic character (formerly sub- Page 1, Clause 1 Scope clause 4.20, now 4.22), insert “or a format character” In the note, update the Unicode Standard version after “control function”. from 4.0 to 4.1. Page 2, Clause 3 Normative references Page 14, Clause 19 Characters in bidirectional context Update the reference to the Unicode Bidirectional Algorithm and the Unicode Normalization Forms as Add ‘Mirrored’ before ‘Character’ in clause title and follows: replace the text of the clause by the following: Unicode Standard Annex, UAX#9, The Unicode Bidi- A class of character has special significance in the rectional Algorithm, Version 4.1.0, [date TBD]. context of bidirectional text. The interpretation and rendering of any of these characters depend on the Unicode Standard Annex, UAX#15, Unicode Nor- state related to the symmetric swapping characters malization Forms, Version 4.1.0, [date TBD]. (see clause F.2.2) and on the direction of the char- acter being rendered that are in effect at the point in the CC-data-element where the coded representa- Page 2, Clause Terms and definitions tion of the character appears. The list of these char- Insert the following text as sub-clause 4.1 and Note; acters is provided in Annex E.1. update all following sub-clause numbers accord- NOTE – That list also represents all characters which have ingly. -

1 Symbols (2286)

1 Symbols (2286) USV Symbol Macro(s) Description 0009 \textHT <control> 000A \textLF <control> 000D \textCR <control> 0022 ” \textquotedbl QUOTATION MARK 0023 # \texthash NUMBER SIGN \textnumbersign 0024 $ \textdollar DOLLAR SIGN 0025 % \textpercent PERCENT SIGN 0026 & \textampersand AMPERSAND 0027 ’ \textquotesingle APOSTROPHE 0028 ( \textparenleft LEFT PARENTHESIS 0029 ) \textparenright RIGHT PARENTHESIS 002A * \textasteriskcentered ASTERISK 002B + \textMVPlus PLUS SIGN 002C , \textMVComma COMMA 002D - \textMVMinus HYPHEN-MINUS 002E . \textMVPeriod FULL STOP 002F / \textMVDivision SOLIDUS 0030 0 \textMVZero DIGIT ZERO 0031 1 \textMVOne DIGIT ONE 0032 2 \textMVTwo DIGIT TWO 0033 3 \textMVThree DIGIT THREE 0034 4 \textMVFour DIGIT FOUR 0035 5 \textMVFive DIGIT FIVE 0036 6 \textMVSix DIGIT SIX 0037 7 \textMVSeven DIGIT SEVEN 0038 8 \textMVEight DIGIT EIGHT 0039 9 \textMVNine DIGIT NINE 003C < \textless LESS-THAN SIGN 003D = \textequals EQUALS SIGN 003E > \textgreater GREATER-THAN SIGN 0040 @ \textMVAt COMMERCIAL AT 005C \ \textbackslash REVERSE SOLIDUS 005E ^ \textasciicircum CIRCUMFLEX ACCENT 005F _ \textunderscore LOW LINE 0060 ‘ \textasciigrave GRAVE ACCENT 0067 g \textg LATIN SMALL LETTER G 007B { \textbraceleft LEFT CURLY BRACKET 007C | \textbar VERTICAL LINE 007D } \textbraceright RIGHT CURLY BRACKET 007E ~ \textasciitilde TILDE 00A0 \nobreakspace NO-BREAK SPACE 00A1 ¡ \textexclamdown INVERTED EXCLAMATION MARK 00A2 ¢ \textcent CENT SIGN 00A3 £ \textsterling POUND SIGN 00A4 ¤ \textcurrency CURRENCY SIGN 00A5 ¥ \textyen YEN SIGN 00A6 -

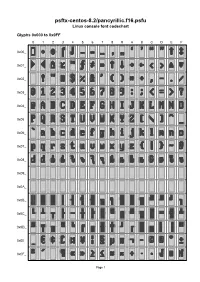

Psftx-Centos-8.2/Pancyrillic.F16.Psfu Linux Console Font Codechart

psftx-centos-8.2/pancyrillic.f16.psfu Linux console font codechart Glyphs 0x000 to 0x0FF 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 A B C D E F 0x00_ 0x01_ 0x02_ 0x03_ 0x04_ 0x05_ 0x06_ 0x07_ 0x08_ 0x09_ 0x0A_ 0x0B_ 0x0C_ 0x0D_ 0x0E_ 0x0F_ Page 1 Glyphs 0x100 to 0x1FF 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 A B C D E F 0x10_ 0x11_ 0x12_ 0x13_ 0x14_ 0x15_ 0x16_ 0x17_ 0x18_ 0x19_ 0x1A_ 0x1B_ 0x1C_ 0x1D_ 0x1E_ 0x1F_ Page 2 Font information 0x018 U+2191 UPWARDS ARROW Filename: psftx-centos-8.2/pancyrillic.f16.psfu 0x019 U+2193 DOWNWARDS ARROW PSF version: 1 0x01A U+2192 RIGHTWARDS ARROW Glyph size: 8 × 16 pixels Glyph count: 512 0x01B U+2190 LEFTWARDS ARROW Unicode font: Yes (mapping table present) 0x01C U+2039 SINGLE LEFT-POINTING ANGLE QUOTATION MARK Unicode mappings 0x01D U+2040 CHARACTER TIE 0x000 U+FFFD REPLACEMENT CHARACTER 0x01E U+25B2 BLACK UP-POINTING 0x001 U+2022 BULLET TRIANGLE 0x01F U+25BC BLACK DOWN-POINTING 0x002 U+25C6 BLACK DIAMOND, TRIANGLE U+2666 BLACK DIAMOND SUIT 0x020 U+0020 SPACE 0x003 U+2320 TOP HALF INTEGRAL 0x021 U+0021 EXCLAMATION MARK 0x004 U+2321 BOTTOM HALF INTEGRAL 0x022 U+0022 QUOTATION MARK 0x005 U+2013 EN DASH 0x023 U+0023 NUMBER SIGN 0x006 U+2014 EM DASH 0x024 U+0024 DOLLAR SIGN 0x007 U+2026 HORIZONTAL ELLIPSIS 0x025 U+0025 PERCENT SIGN 0x008 U+201A SINGLE LOW-9 QUOTATION MARK 0x026 U+0026 AMPERSAND 0x009 U+201E DOUBLE LOW-9 0x027 U+0027 APOSTROPHE QUOTATION MARK 0x00A U+2018 LEFT SINGLE QUOTATION 0x028 U+0028 LEFT PARENTHESIS MARK 0x029 U+0029 RIGHT PARENTHESIS 0x00B U+2019 RIGHT SINGLE QUOTATION MARK 0x02A U+002A ASTERISK 0x00C U+201C LEFT DOUBLE