Oic-50-1-2016

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

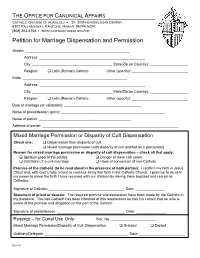

Petition for Marriage Permission Or Dispensation

Form M2 Revised 9/2009 DIOCESE OF SPOKANE PETITION FOR MARRIAGE PERMISSION OR DISPENSATION GROOM BRIDE Name Name Address Address City, State City, State Date of Birth Date of Birth RELIGION Catholic Catholic Parish: Parish: Place: Place: Baptized non-Catholic Baptized non-Catholic Denomination: Denomination: Unbaptized Unbaptized Scheduled date and place for marriage: The following dispensation and permissions may be granted by the pastor for marriages celebrated within the territory his parish. Otherwise, the petition is submitted to the Local Ordinary. A. Disparity of Cult (C. 1086, a Catholic and a non-baptized person). See reverse side. B. Mixed Religion (and, if necessary, disparity of cult, C. 1124). See reverse side. C. Natural obligations from a prior union (C. 1071 3°). Marriage is permitted only when the pastor or competent authority is sure that these obligations are being fulfilled. D. Permission to marry when conditions are attached to a declaration of nullity—granted only if these stipulations have been fulfilled. (Cf. C. 1684) By virtue of the faculties granted to pastors of the Diocese of Spokane, I hereby grant the above indicated permissions/dispensation. Pastor: Date: (This document is retained in the prenuptial file) See p. 2 of this form for dispensations and permissions reserved to the Local Ordinary (Diocesan bishop, Vicar General or their delegate). Page 1 of 2 Form M2 In cases of Mixed Religion (Catholic and a baptized non-Catholic) or Disparity of Cult, the Catholic party is to make the following promise in writing or orally: “I reaffirm my faith in Jesus Christ and, with God’s help, intend to continue living that faith in the Catholic Church. -

Seventh Pastoral Letter of Catholic

SEVENTH Pastoral Letter PASTORAL LETTER TO PRIESTS “As the Father hath sent me, even so send I you.” (John 20:21) Feast of the Dormition, 15 August 2004 INTRODUCTION To our beloved sons and brothers, the priests, “Grace, mercy, and peace, from God our Father and Jesus Christ our Lord.” (1 Timothy 1: 2) We greet you with the salutation of the Apostle Paul to his disciple, Timothy, feeling with him that we always have need of the “mercy and peace of God,” just as we always have need of renewal in the understanding of our faith and priesthood, which binds us in a peculiar way to “God our Father and Jesus Christ our Lord.” We renew our faith, so as to become ever more ready to accept our priesthood, and assume our mission in our society. The Rabweh Meeting We held our twelfth annual meeting at Rabweh (Lebanon), from 27 to 31 October 2002, welcomed by our brother H.B. Gregorios III, Patriarch of Antioch, of Alexandria and of Jerusalem for the Melkite Greek Catholics. We studied together the nature of the priesthood, its holiness and everything to do with our priests, confided to our care and dear to our heart. Following on from that meeting, we address this letter to you, dear priests, to express to all celibate and married clergy, our esteem and gratitude for your efforts to make the Word and Love of God present in our Churches and societies. Object of the letter “We thank God at every moment for you,” dear priests, who are working in the vineyard of the Lord in all our eparchies in the Middle East, in the countries of the Gulf and in the distant countries of emigration. -

Who Are Christians in the Middle East?

Who Are Christians in the Middle East? Seven Churches, each bearing a great and ancient history with Patriarch, who chose as his patriarchal seat the monastery at unique liturgical traditions and culture, comprise the Catho- Bzommar, Lebanon. After a brief relocation to Constantinople, lic Church in the Middle East. Each of these Churches is in the Patriarch of Cilicia of Armenian Catholics returned his seat full communion with Rome, but six with an Eastern tradition to Bzommar, with his residence and offices in Beirut, Lebanon. are sui iuris, or self-governing, and have their own Patriarchs. The Chaldean Catholic Church has almost 500,000 mem- All these Churches are Arabic-speaking and immersed in Ar- bers, with about 60 percent residing in the Middle East. The abic culture. Chaldeans are historically concentrated in Iraq as they came The Maronite Catholic Church is the largest of the East- from the Assyrian Church of the East. In 1552, a group of As- ern Catholic Churches in the Middle East at around 3 million syrian bishops decided to seek union with Rome. Although members. It has a strong presence in Lebanon, with smaller Pope Julius III proclaimed Patriarch Simon VIII Patriarch “of communities in Syria, Jordan, Cyprus, and the Holy Land. the Chaldeans,” pro- and anti-Catholic parties struggled with- However, slightly over half its members have emigrated from in the Assyrian Church of the East until 1830, when another the Middle East to countries such as Argentina, Brazil, Aus- Chaldean Patriarch was appointed. The Patriarch of Babylon of tralia, Mexico, Canada, and the United States. -

SC for March 30.Qxd

SC for March 30.qxd 4/1/2008 9:35 AM Page 1 Sooner Catholic Serving the People of the Archdiocese of Oklahoma City Volume 35, Number 6 * March 30, 2008 Benedictines, Archbishop Holy Week 2008 Agree to Changes In Parish Roles SHAWNEE — The Benedictine monks of St. Gregory’s Abbey in Shawnee will soon entrust the parishes under their care in Pottawatomie and Seminole counties to the pastoral leadership of the Archdiocese of Oklahoma City. The Most Reverend Eusebius Beltran, Archbishop of Oklahoma City, and the Rt. Reverend Lawrence Stasyszen, O.S.B., Abbot of St. Gregory’s Abbey, announced the shift in parish administration at a meeting with parish representatives held at Saint Benedict Parish in Shawnee on March 15. Archbishop Beltran hosted the meeting in order to share information with parish repre- sentatives and to answer questions regarding the immediate effects of the change. During the meeting, Archbishop Beltran noted that “the Catholic Church is structured along geographical lines so that every Catholic person and institution is under the jurisdiction of the local bishop. This area is called a diocese or archdiocese. Through the spiritual direction of the bishop or archbishop and extended through smaller areas (parishes), the faith is transmitted, celebrated and grows. Therefore, the Archdiocese of Oklahoma City will be responsible for appointing pastors to the area formerly served by the Benedictine Monks of Shawnee.” Congregations at Saint Cecilia Church in Maud, Saint Vincent de Paul Church in McLoud, Immaculate Conception Church in Seminole, Saint Benedict Church in Shawnee, Saint Joseph Church in Wewoka and Saint Mary Church in Wanette will be affected by the change in administration. -

Christian-Muslim Relations in a Future Iraq: Recent Media Comment

Christian-Muslim relations in a future Iraq: Recent media comment This is the first of a monthly series on an aspect of Christian-Muslim relationships. Reports in this series will firstly seek to provide a factual digest of news reports or other published information on the subject under discussion. They will also include a brief conclusion – which will contain the element of evaluation. Structure of following information. Basic information regarding the situation of Christians in Iraq Precis of major article in The Tablet March 15 2003 Information from Iraqi diaspora sources Information based on comment/direct news etc of Christians in Iraq/Middle East Possible difficulties relating to Western Christian Conclusions There is both a substantial – and also historic – Christian community in Iraq. A reasonable estimate seems to be perhaps 750,000 out of a total population of approximately 24 million. There are also considerable numbers of Christians of Iraqi origin living outside the country (in some cases for generations). Detroit,in the US, is a particular base. What is the attitude of the Iraqi Christian community to the war and what does the future hold for them? They have received a reasonable amount of attention in the news media in recent weeks – and the following comments are based on that as well as an extended conversation with a senior Christian Iraqi currently resident in the United Kingdom. Basic information regarding the situation of Christians in Iraq (drawn from published information, and conversations) The ‘core community’ of Iraqi Christians are the Chaldean Catholics. (? 500,000). The spiritual ancestors of this community were members of the ancient Church of the East (who did not accept the Council of Ephesus and were then designated as ‘Nestorians’). -

Chancery Training Day – Notes

DIOCESE OF BRENTWOOD Chancery Training Day CHANCERY OFFICE Wednesday, 11th March 2020 Chancery Training Day Wednesday, 11th March 2020 Agenda: 1030: Coffee and Arrivals 1100: Welcome and Notices 1110: Preparing for Marriages I 1150: BREAK 1200: Preparing for Marriages II 1230: Parochial Registers and Archives 1300: Questions 1315: LUNCH 1400: Preparing for RCIA 1430: END Session One: Preparing for Marriages Paperwork basics: o The paperwork for marriage is to be done in the parish in which at least one of the parties resides. If the parties live separately they can choose to do the paperwork in either parish, not both (unless it is a one party application). Given that some (if not most) couples co-habit before marriage this means that independent of where the parties plan to marry, the paperwork needs to be done in the home parish. o Problems arise when those not regularly practicing don’t realise there is paperwork to be completed in the home parish and, if they are marrying outside the home parish/diocese, the cleric who is marrying them doesn’t mention anything. Perhaps parishes will consider a biennial announcement/notice to remind couples and families of this. o The Chancery Office will not process marriage papers sent in more than six months in advance of the wedding date. In the peak season it may not be possible to process papers sent in fewer than six to eight weeks before the wedding date. Please contact us in advance of sending in these papers. Please note that this does not mean that parishes shouldn’t start the paperwork more than six months before the wedding date. -

The Chaldean Americans: Changing Conceptions of Ethnic Identity

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 223 740 UD 022 551 , AUTHOR Sengstock, Mary C. TITLE The Chaldean Americans: Changing Conceptions of Ethnic Identity. First Edition. INSTITUTION Center for Migration Studies, Inc., Staten Island, N.Y. REPORT NO ISBN-0-913256-43-9 PUB DATE 82 NOTE // 184p.; Some research supported by_a Faculty , Grant-In-Aid from Wayne State University. Not available in paper copy due to institution's 'restrictions. AVAILABLE FROM Center for Migration Studies, Inc., 209Flagg Place, . Staten Island, NY 10304 ($9.95)., ,PUB TYPE llooks (010) EDRS PRI'CE MF01 Plus Postage. PC Not Available from EDRS. _DESCRIPTORS(' *Acculturation; *Adjustment (to Environment); Catholics; Church Role; *Cultural Influences; Ethnic Groups;'*Ethnicity; Family Striicture; Group Unity; *Immigrants; Nationalism; Political Influences; , Public Policy; Religious Cultural Groups; Small Businesses; Social Structure; *Socioeconomic Influences s IDENTIFIERS *Chaldean Americans; Iraqis ABSTRACT Chaldean Americans in\ Detroit, Michigan, a growing community of Roman Catholic immigrants from Iraq, are thefocus of this study. A description is given of theDetroit Chaldean community centers around three key institutions, namelythe church, the family, and the ethnic occupation or communityeconomic-enterprise, and of how these institutions have beenaffected by the migration experience and by contact with the new culture. An analysis ofthe social setting of migration-examines religious and economicdeterminants of migration to America, migration effects on the_Detroitcommunity, and Chaldeane relationships with other socialgroeps in Detroit. An exploration of Chaldeans' adaptation to their new settingconsiders' assimilation and acculturation pr cesses, changes insocial structure and values, creation of a balance etween old country patterns and new practices, and the developmentof an ethnic identity and a sense of nationalism. -

SEIA NEWSLETTER on the Eastern Churches and Ecumenism

SEIA NEWSLETTER On the Eastern Churches and Ecumenism _______________________________________________________________________________________ Number 182: November 30, 2010 Washington, DC The Feast of Saint Andrew at sues a strong summons to all those who by HIS IS THE ADDRESS GIVEN BY ECU - The Ecumenical Patriarchate God’s grace and through the gift of Baptism MENICAL PATRIARCH BARTHOLO - have accepted that message of salvation to TMEW AT THE CONCLUSION OF THE renew their fidelity to the Apostolic teach- LITURGY COMMEMORATING SAINT S IS TRADITIONAL FOR THE EAST F ing and to become tireless heralds of faith ANDREW ON NOVEMBER 30: OF ST. ANDREW , A HOLY SEE in Christ through their words and the wit- Your Eminence, Cardinal Kurt Koch, ADELEGATION , LED BY CARDINAL ness of their lives. with your honorable entourage, KURT KOCH , PRESIDENT OF THE PONTIFI - In modern times, this summons is as representing His Holiness the Bishop of CAL COUNCIL FOR PROMOTING CHRISTIAN urgent as ever and it applies to all Chris- senior Rome and our beloved brother in the UNITY , HAS TRAVELLED TO ISTANBUL TO tians. In a world marked by growing inter- Lord, Pope Benedict, and the Church that PARTICIPATE IN THE CELEBRATIONS for the dependence and solidarity, we are called to he leads, saint, patron of the Ecumenical Patriarchate proclaim with renewed conviction the truth It is with great joy that we greet your of Constantinople. Every year the Patriar- of the Gospel and to present the Risen Lord presence at the Thronal Feast of our Most chate sends a delegation to Rome for the as the answer to the deepest questions and Holy Church of Constantinople and express Feast of Sts. -

THE RUSSIAN ORTHODOX CHURCH Department for External Church Relations

THE RUSSIAN ORTHODOX CHURCH Department for External Church Relations DECR chairman expresses condolences to the Chaldean Catholic Patriarch of Babylon over demise of his predecessor Metropolitan Hilarion of Volokolamsk, chairman of the Moscow Patriarchate’s Department for External Church Relations, sent the following condolences to His Beatitude Mar Louis Raphaël I Sako over the demise of his predecessor, His Beatitude Patriarch Emeritus Emmanuel III Cardinal Delly: Your Beatitude: Please accept my sincere condolences over the demise of your predecessor, Mar Emmanuel III Delly, Patriarch Emeritus of Babylon. The Lord has judged His Beatitude to lead the Chaldean Catholic Church at the exceptionally hard time for Iraq. In the years of his office, His Beatitude Patriarch Emmanuel witnessed military intervention which inflicted destruction and was followed by the murderous war and massive exodus of Christians from the Middle East – the land of their predecessors with ancient history that has been preserving Biblical spirit. His Beatitude remained firm in his faith in God’s Providence, kept up love of the people and his kind, truly Christian attitude to any human person irrespective of his political views, cultural traditions, national or religious background. He gained confidence and profound respect of many contemporaries. May the Lord grant him eternal memory! With sincere condolences and brotherly love in Christ, /+ Hilarion/ Metropolitan of Volokolamsk Chairman Department for External Church Relations Moscow Patriarchate Source: https://mospat.ru/en/news/51571/ Powered by TCPDF (www.tcpdf.org). -

1 Summary English Edition N. 530 January

Englliish Ediitiion n. 530 January - Aprriill 2008 Summary The Paths of our Mission 1 The Paths of our Mission Dear Confreres, 2 In this Paschal Season, we are illuminated by the Light of Official News Items the Resurrection, a Light which makes us into witnesses to the 4 Risen One. Like the holy women, we are told to leave the tombs Latin America and – our tombs – and to go to Galilee… the Galilee of the nations Caribbean Scholasticate where we are awaited. The mystery of the Resurrection is also a 5 mystery of Mission: the Holy Spirit sends us out to all nations… 75th Anniversary SMM in Congo RD From January to September this year, the General 7 Council is on “mission”, to the “Galilee” of the Congregation; 75th Anniversary SMM in they are going out to all nations… Madagascar 8 Father General, after his visit to the Congo in January, 50th Anniversary of the went to Great Britain to perfect his use of the English language. «Lourdes in Litchfield» We cannot give too much encouragement to the younger ones Shrine (USA) among us to spare nothing in the effort to learn other languages, 9 a necessary condition for internationality… At the end of April, SMM Web Sites he will be in Haiti. During the Summer, he will be going for a 10 long visit to Indonesia, though it will be short enough when we With the Christians of Iraq consider the size of this immense country and the number of confreres… 10 Association of Mary, Father Don LaSalle has left for the United States, Queen of All Hearts in Canada, the Philippines and India; and he is making Slovakia preparations to return to Uganda, Kenya, Malawi and Peru. -

Dispensation-Form.Pdf

THE OFFICE FOR CANONICAL AFFAIRS CATHOLIC DIOCESE OF HONOLULU ST. STEPHEN DIOCESAN CENTER 6301 PALI HIGHWAY, KĀNE'OHE, HAWAI'I 96744-5224 [808] 203-6766 WWW.CATHOLICHAWAII.ORG/CIC Petition for Marriage Dispensation and Permission Groom: ____________________________________________________ Address: _____________________________________________________ City: ________________________________________ State/Zip (or Country): ___________________ Religion: Latin (Roman) Catholic Other (specify): ____________________________ Bride: ____________________________________________________ Address: _____________________________________________________ City: ________________________________________ State/Zip (or Country): ___________________ Religion: Latin (Roman) Catholic Other (specify): ____________________________ Date of marriage (or validation): _______________________________________ Name of priest/deacon (print): ____________________________________________________ Name of parish: ______________________________________________ Address of parish: ____________________________________________________________________ Mixed Marriage Permission or Disparity of Cult Dispensation Check one: Dispensation from disparity of cult Mixed marriage permission (with disparity of cult granted as a precaution) Reason for mixed marriage permission or disparity of cult dispensation – check all that apply: Spiritual good of the parties Danger of mere civil union Validation of a civil marriage Hope of conversion of non-Catholic Promise of the Catholic (to -

Abstract Title of Dissertation: NEGOTIATING the PLACE OF

Abstract Title of Dissertation: NEGOTIATING THE PLACE OF ASSYRIANS IN MODERN IRAQ, 1960–1988 Alda Benjamen, Doctor of Philosophy, 2015 Dissertation Directed by: Professor Peter Wien Department of History This dissertation deals with the social, intellectual, cultural, and political history of the Assyrians under changing regimes from the 1960s to the 1980s. It examines the place of Assyrians in relation to a state that was increasing in strength and influence, and locates their interactions within socio-political movements that were generally associated with the Iraqi opposition. It analyzes the ways in which Assyrians contextualized themselves in their society and negotiated for social, cultural, and political rights both from the state and from the movements with which they were affiliated. Assyrians began migrating to urban Iraqi centers in the second half of the twentieth century, and in the process became more integrated into their societies. But their native towns and villages in northern Iraq continued to occupy an important place in their communal identity, while interactions between rural and urban Assyrians were ongoing. Although substantially integrated in Iraqi society, Assyrians continued to retain aspects of the transnational character of their community. Transnational interactions between Iraqi Assyrians and Assyrians in neighboring countries and the diaspora are therefore another important phenomenon examined in this dissertation. Finally, the role of Assyrian women in these movements, and their portrayal by intellectuals,