Managing Airports: a Test of the New Public Management

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Liste Anerkannter Prüfer/Examiner Gemäß Part-FCL

Austro Control Österreichische Gesellschaft für Zivilluftfahrt mbH Wagramer Straße 19 A-1220 Wien Liste anerkannter Prüfer/Examiner gemäß Part-FCL „Diese Liste gibt den Stand zum Veröffentlichungsdatum wieder! Nach diesem Termin könnten weitere Ausbildungserlaubnisse erteilt sein, welche zur nächsten Veröffentlichung eingepflegt werden.“ "This list shows the status as of the publication date! After this date further privileges could be issued, which will be included in the next publication." Name Authorisation-Nr. Authorisation Gültig bis Kontaktadresse Tel-Nr. / Mobil / Fax / E-Mail Name Authorisation-no Authorisation Valid until Contact address tel-no/mobile/fax/e-mail Aberham Gerhard AT.FCL.6977.TRE TRE B777/787 31.12.2022 Austrian Airlines M: +43/5/176666641 Office Park 2 E: [email protected] A-1300 Flughafen Wien Ager Lis-Marie AT.FCL.11712.TRE TRE BD-700, TRE G7500 31.12.2021 Stumpergasse 29/1/22 M: +43/664/8561208 A-1060 Wien E: [email protected] Aichinger Gerlinde AT.FCL.11294.CRE.FE CRE SEP(land), CRE TMG, FE(A) 31.10.2022 blue danube flying M: +43/664/4087555 Obere Donaulände 63 E: [email protected] A-4020 Linz Aigner Peter AT.FCL.5795.CRE.FE.FIE.IRE.TRE CRE SEP(land), FE(A), FIE(A), IRE(A), TRE 28.02.2022 Starflight GmbH M: +43/699/18150000 C510, SEN Flugplatz E: [email protected] A-2540 Bad Vöslau Aigner Roland AT.FCL.5712.TRE TRE EMB170 30.09.2022 Austrian Airlines Office Park 2 A-1300 Flughafen Wien Akinjobi Ayo AT.FCL.39352.SFE SFE C680, SFE G-V 30.09.2023 FlightSafety International Farnborough -

IFFR Flyer July07.Indd

THE ROTARY Flyer - World Bulletin INTERNATIONAL FELLOWSHIP OF FLYING ROTARIANS WORLD PRESIDENT SECRETARY-TREASURER BULLETIN EDITOR BRIAN SOUTER ROY MARSDEN ROSS EWING 5 Baxter Way 33 Kurupae Road 8 Haddon Lane Karori Harewood Wellington 6012 Taupo 3330 Christchurch 8051 New Zealand New Zealand New Zealand Phone: +64 4 476-7910 Phone: +64 7 378-2673 Phone: +64 3 360-2400 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] From the International President GREETINGS to all. at least one prospective member What a wonderful introduction or IFFR member to attend their to my new role as President first fly-in or fly-about and share to be able to participate in what we all enjoy in the year the Scandinavian fly-about in ahead. Like most beers, there are June. Thank you, Bo, and all no bad fly-ins but some may be your helpers and to my flying better than others. chauffeur for the occasion, Talking of fly-about’s, it was Audun Johnsen – they are really pleasing to me – as it was such wonderful memories that no doubt to Bo Johnsson – to Jeannette and I can savor in the see the dynamics of the decision Brian Souter of New Zealand (right) takes over from his predecessor, Angus Clark. years to come. We really enjoyed making process to postpone the meeting many wonderful people flight from Fagernes to Sindal the delay enabled some to enjoy on our first visit to Scandinavia. for a day. My thanks to Alan tramping the hills behind our Fellowship is the reason we all Grady from Australia, Angus Storefjell Hotel. -

NM Monthly Network Operations Report - Analysis – March 2018 TLP: GREEN Page 1

Monthly Network Operations Report Analysis – March 2018 NM Monthly Network Operations Report - Analysis – March 2018 TLP: GREEN Page 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS 2 NOTICE 2 1. TOTAL TRAFFIC 3 2. ATFM DELAY AND ATTRIBUTIONS 6 3. EN-ROUTE ATFM DELAYS 7 En-Route ATFM Delay per Location 7 En-Route ATFM Delay per Delay Group 8 En-Route ATFM Delay per Flight 9 En-Route ATFM Delay Year-To-Date 10 4. AIRPORT/TMA ATFM DELAYS 11 Airport/TMA ATFM Delay per Location 11 Airport/TMA ATFM Delay per Delay Groups 11 Airport/TMA ATFM Delay per Flight 12 Airport/TMA ATFM Delay Year-To-Date 12 5. DAILY EVOLUTION 12 6. ALL AIR TRANSPORT DELAYS (SOURCE: CODA) 13 7. ATFM SLOT ADHERENCE 14 8. SIGNIFICANT EVENTS AND ISSUES 14 Planned Events 14 ACC 14 Airports 15 Disruptions 15 9. NM ADDED VALUE 16 NOTICE Traffic and Delay Comparisons All traffic and delay comparisons are between report month and equivalent month of previous year, unless otherwise stated. Graphics All graphs in chapter 3 and chapter 4 are in average minutes of ATFM delay per day, unless otherwise stated. NM Area All figures presented in this report are for the geographical area that is within Network Manager’s responsibility (NM area). For further information on the NM Area go to the Reporting Assumptions and Descriptions document available on the EUROCONTROL website at http://www.eurocontrol.int/articles/network-operations-monitoring-and-reporting. Regulation Reason Groupings The table below shows the colour coding used in the report charts. EN-ROUTE CAPACITY (ATC) AIRPORT CAPACITY (ATC) EN-ROUTE STAFFING (ATC) AIRPORT STAFFING (ATC) EN-ROUTE DISRUPTIONS (ATC) AIRPORT DISRUPTIONS (ATC) EN-ROUTE CAPACITY AIRPORT CAPACITY EN-ROUTE DISRUPTIONS AIRPORT DISRUPTIONS EN-ROUTE EVENTS AIRPORT EVENTS EN-ROUTE WEATHER AIRPORT WEATHER For further information on the regulation reason groupings, go to the Reporting Assumptions and Descriptions document available on the EUROCONTROL website at http://www.eurocontrol.int/articles/network-operations-monitoring-and-reporting. -

Review of the Aviation Fuel Markets in Jersey and Guernsey Redacted

Review of the aviation fuel markets in Jersey and Guernsey Redacted version Document No: CICRA 14/58 November 2014 Guernsey Competition and Regulatory Authority Jersey Competition Regulatory Authority Suites B1 & B2, Hirzel Court, 2nd Floor Salisbury House, St Peter Port, Guernsey, GY1 2NH 1-9 Union Street, St Helier, Jersey, JE2 3RF Tel: +44 (0)1481 711120 Tel: +44 (0)1534 514990 Web: www.cicra.gg Web: www.cicra.je 1 Contents EXECUTIVE OVERVIEW & SUMMARY OF RECOMMENDATIONS……………………………………………1 1. INTRODUCTION…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….6 2. BACKGROUND……………………………………………………………….………………………………………………………6 3. VOLUMES & PRICES………………………………………………………………………………………………………………6 4. COST ANALYSIS……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………14 5. BARRIERS TO ENTRY………………………………..………………………………………………………………………….18 6. CONCLUSIONS…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….19 7. RECOMMENDATIONS………………………………….………………………………………………………………………20 Annex 1 Terms of Reference Annex 2 Detailed Netback analysis of fuel products Annex 3 Previous Reports Annex 4 FRAND – Fair Reasonable and Non-Discriminatory terms 2 Executive Overview This review of the supply of aviation fuel in Jersey and Guernsey was conducted by the Channel Islands Competition and Regulatory Authorities (CICRA) in response to a request from the Minister for Economic Development in Jersey and the Commerce and Employment Board in Guernsey1. Background At the time of the review, FSCI (Fuel Supplies CI Limited) was the sole supplier of aviation fuel at Jersey and Guernsey airports. However since the beginning of September, there have been significant changes to the fuel supply arrangements at Jersey Airport. Prior to this change, FSCI operated the airport fuel facilities at each airport, and was the single importer, retailer and distributor of aviation fuel in Jersey and Guernsey. Two grades of aviation fuel are used in the Channel Islands; Jet A1 (also known as kerosine/kerosene) used by jet or turbo-prop aircraft, and Avgas (also known as gasoline) used for private or light aircraft. -

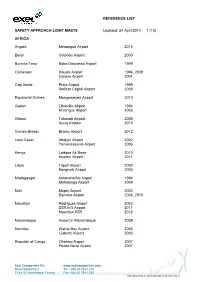

Reference List Safety Approach Light Masts

REFERENCE LIST SAFETY APPROACH LIGHT MASTS Updated: 24 April 2014 1 (10) AFRICA Angola Menongue Airport 2013 Benin Cotonou Airport 2000 Burkina Faso Bobo Diaulasso Airport 1999 Cameroon Douala Airport 1994, 2009 Garoua Airport 2001 Cap Verde Praia Airport 1999 Amilcar Capral Airport 2008 Equatorial Guinea Mongomeyen Airport 2010 Gabon Libreville Airport 1994 M’vengue Airport 2003 Ghana Takoradi Airport 2008 Accra Kotoka 2013 Guinea-Bissau Bissau Airport 2012 Ivory Coast Abidjan Airport 2002 Yamoussoukro Airport 2006 Kenya Laikipia Air Base 2010 Kisumu Airport 2011 Libya Tripoli Airport 2002 Benghazi Airport 2005 Madagasgar Antananarivo Airport 1994 Mahajanga Airport 2009 Mali Moptu Airport 2002 Bamako Airport 2004, 2010 Mauritius Rodrigues Airport 2002 SSR Int’l Airport 2011 Mauritius SSR 2012 Mozambique Airport in Mozambique 2008 Namibia Walvis Bay Airport 2005 Lüderitz Airport 2005 Republic of Congo Ollombo Airport 2007 Pointe Noire Airport 2007 Exel Composites Plc www.exelcomposites.com Muovilaaksontie 2 Tel. +358 20 754 1200 FI-82110 Heinävaara, Finland Fax +358 20 754 1330 This information is confidential unless otherwise stated REFERENCE LIST SAFETY APPROACH LIGHT MASTS Updated: 24 April 2014 2 (10) Brazzaville Airport 2008, 2010, 2013 Rwanda Kigali-Kamombe International Airport 2004 South Africa Kruger Mpumalanga Airport 2002 King Shaka Airport, Durban 2009 Lanseria Int’l Airport 2013 St. Helena Airport 2013 Sudan Merowe Airport 2007 Tansania Dar Es Salaam Airport 2009 Tunisia Tunis–Carthage International Airport 2011 ASIA China -

"Airports" (PDF)

Specialist services for the airport life cycle Let's talk aeronautics Specialist services for the airport life cycle AERTEC provides specialist Aviation consultancy and design services to a wealth of Aviation- sector clients, including airport operators, construction firms, service providers, airlines, government agencies, investors, and financial aeronautics institutions. Our company also provides consultancy services and solutions development for Airport Technological Systems. Adolfo Suárez Madrid-Barajas Airport Spain Let's talk Let's M A D We create value for Aviation clients Consultancy through integrated Conception services and independent specialist advice Operations Development Operational Planning assessment & Design Airport Technology #Airports Our Services Feasibility studies Airport solutions for landside/airside and analysis Studies and plans ¬ Policy and sector studies ¬ Airport masterplanning ¬ Air transport market studies ¬ Feasibility studies ¬ Traffic forecasting ¬ Airport planning studies ¬ Business advisory ¬ Aeronautical safety studies ¬ Transaction support ¬ Design of flight procedures and Consultancy and due diligence airspace compatibility studies ¬ Obstacle limitation surface studies ¬ Operational safety studies ¬ Capacity studies: airside and landside Brussels South Charleroi Airport Planning & Design ¬ Aircraft flow simulations (AirTop/Simmod/AeroTURN) C R L Belgium ¬ Passenger flow simulations (AirTop/CAST) ¬ Aircraft noise contour studies (AEDT) ¬ Airport planning application Airfields ¬ Preliminary plans, -

St. Louis Lambert International Airport Request for Qualifications Gateway Airport Partners Response

St. Louis Lambert International Airport Request for Qualifications Gateway Airport Partners Response 01 November 2019 Confidential [email protected] 2020-01-16 15:20:50 +0000 Strategic Advisor NOTICE: The Data on pages of this proposal identified by an asterisk (*) contains technical or financial information constituting trade secrets. The proposer requests that such information be used only for the evaluation of the proposal, but understands that any disclosure will be limited to the extent that the City considers proper under the law. If the City enters into an agreement with this proposer, the City shall have the right to use or disclose such information as provided in the agreement, unless otherwise obligated by law. STRICTLY CONFIDENTIAL This text does not print STRICTLY CONFIDENTIAL Cover Page Registration of Qualifications: Proposed Long-Term Lease of St. Louis Lambert International Airport Ontario Teachers’ Pension Plan Board (“OTPP”), Ontario Airports Investments Limited (“OAIL”) and Copenhagen Airports International (“CAI”) (together the “Team”), along with our strategic real estate advisor Cadillac Fairview (“CF”) are pleased to submit this response to the Request for Qualifications for the proposed long-term lease to operate St. Louis Lambert International Airport (“STL”). STL represents an exciting opportunity for the team to lease a world-class airport asset. We believe that our team offers a compelling proposition for the City of St. Louis based on our unrivalled global experience in the stewardship of airports and other infrastructure assets. OTPP has invested in airport assets since 2001, and has the distinct advantage of its wholly-owned specialized airport investment manager OAIL, who has been working closely with OTPP since 2011. -

Jennifer Miller Contact Core Skills Qualifications Likes

WEB & CREATIVE DESIGN JENNIFER MILLER & PROJECT MANAGEMENT CV CONTACT CORE SKILLS QUALIFICATIONS LIKES AND INTERESTS 160a High Street Adobe Photoshop GNVQ Art & Design Art and design Maldon Adobe Illustrator Braintree College Painting Essex Adobe inDesign 2000 - 2002 Glass CM9 5BA Microsoft office Textiles Adobe inDesign Digital 0787 403 9052 Joomla Adobe Illustrator Wordpress Adobe Photoshop Sailing [email protected] CSS Exeter College 2012 - Instruction HTML - Racing Portfolio: Windsurfing www.d-eye.co.uk/portfolio Presenting / Pitching Paddleboarding Logo design Brand guidelines Dancing, singing & acting Website wireframing & responsive design - Pantomine Project management for web development - Musicals and design - Wedding Band Singer Concept generation & development Market research Client training Experience in Server administration (Linux) Mysql Vtiger CRMs WEB & CREATIVE DESIGN JENNIFER MILLER & PROJECT MANAGEMENT CV CAREER HISTORY PROFILE BRANDS WORKED ON Design Eye Jennifer Miller. Designer, with a life long enthusiasm and passion for Design. Gatwick Airport, Birmingham Airport, 2013 - 2018 Southampton Airport, Glasgow Airport, For the past 6 years I have been working as a website and creative Cardiff Airport, Newquay Airport Clystnet Web Development designer and as project manager with many top UK companies. Aberdeen Airport, London Southend Airport 2013 - 2018 Specialising in websites, branding and web development. Belfast International Airport, Belfast City Airport, Exeter Airport, Broadclyst Primary School Working both independently with clients as well as with other Designers, Leeds Airport, Derry Airport 2013 - 2017 Creative Directors and Account Executives in working up concepts and Guernsey Airport, Jersey Airport, visuals, amending and progressing designs. I have an approachable, easy Rezcomm CRM, Rezcomm B2B website, The Cornerstone Teaching Academy manner and am confident at presenting my work. -

Australia Bahrain Brazil International Stores Address List

Last updated 03 March 2020 International Stores Address List Australia Location Address Melbourne Airport, T2 Airside CTN Melbourne Airport, T2 Landside Melbourne Airport, T2 Pier Melbourne Airport, T2 Pier D WHSmith Melbourne Airport, T3 Landside Mezzanine Melbourne Airport VIC 3045, Melbourne Airport, T3 Airside Pier Australia Melbourne Airport, T4 Landside Melbourne Airport, T4 Pier G Melbourne Airport, T4 Airside Melbourne Airport, T4 Pier F Southern Cross Station, Ground Floor WHSmith, Southern Cross Station, Adderley Street, Southern Cross Station, First Floor Docklands, VIC 3008 Sydney International Airport, T1 Arrivals Unit 1 Sydney International Airport, T1 Arrivals Unit 2 Sydney International Airport, T1 Pier B WHSmith, Sydney International Airport, T1 Pier B Satellite Sydney International Airport, Sydney International Airport, T1 Pier A Sydney, NSW2020 Sydney International Airport, T1 Pier C Sydney International Airport, T1 Pier C Satellite Sydney International Airport, T1 Landside W H Smith, Tenancy 4/5, Lower Ground Floor, Morven Brown Building, Middle Kensington Campus, University of New South Wales, The Quad The University of NSW, UNSW Sydney, NSW, 2052, Australia W H Smith, Ground Floor, The Quadrangle, Middle Kensington Campus, The University of NSW, University of New South Wales, Morvern Brown UNSW Sydney, NSW, 2052, Australia Adelaide International Airport, Arrivals WHSmith Express, Arrivals Area, Adelaide Airport, 1 James Schofield Dr, SA 5950, Australia Blacktown Hospital (2 WHSmith Units) Blacktown Hospital, Blacktown Road, Blacktown NSW 2148. Liverpool Hospital, WHSmith Express Liverpool Hospital, Corner of Elizabeth and Goulburn Streets, LIVERPOOL NSW 2170 Fresh Plus Hornsby Hospital Hornsby Ku-ring-gai Hospital, Palmerston Road, HORNSBY NSW 2077 Fresh Plus Port Macquarie Hospital Macquarie Hospital, Wrights Road, Port Macquarie, NSW 2444, Australia Fresh Plus Kempsey Hospital Kempsey Hospital, 119 River Street, Kempsey, NSW 2440, Australia Fresh Plus Blacktown Hospital Blacktown Hospital, Blacktown Road, Blacktown NSW 2148. -

Annual Report

ANNUAL REPORT 2015 GUERNSEY AIRPORT ANNUAL REPORT - 2015 Contents Executive Summary 3 Introduction 5 Review of 2015 6 o Guernsey Passenger & Aircraft Statistics 6 o Major Incidents 7 o Pavements Project Update 8 o Management & General Highlights 8 Appendices 10 o 1). Financial Details 10 o 2). Organisation Structure 12 o 3). Acknowledgements & Contact Details 12 2 GUERNSEY AIRPORT ANNUAL REPORT - 2015 1). Executive Summary 2015 was a year of consolidation and a restoration of ‘business as usual ’ at Guernsey Airport, following a few years of significant change. 2014 had seen a major upheaval of carriers and routes and some impacts of those continued in our statistics through Q1 2015, at least until we passed the annual anniversary of these changes in March. This period of consolidation also enabled us to embark on other projects that had taken a lower priority, including the launch of our new website, publication of our Business Plan for the period 2015 – 2025 and a full emergency exercise which was held in November 2015 after a short delay while project works were underway. Significant events of the year included: Other keyOverall events passenger in the year numbers are summarised throughout below, the withyear moreremained detail remarkably following in cons thisis report.tent, albeit slightly down (-0.4%) on 2014. Passenger movements to and from the UK achieved a new high point last year with 80% of our passengers moving to and from the UK. Aircraft movements decreased over the year with fewer, fuller and larger aircraft operating in 2015 than in 2014. Total aircraft movements for the year 2015 were 7% lower than in 2014, and 20% less than in 2013, marking in stark terms the move to larger fleet sizes over the past 24 months. -

Isle of Man Airport

Manx Marine Environmental Assessment Infrastructure Isle of Man Airport Aerial image of Isle of Man Airport, with Derbyhaven Bay. Photo: Department of Infrastructure (2011). Chapter 6.4 October 2018 (2nd edition) Lead author: Ann Reynolds - Department of Infrastructure MMEA Chapter 6.4 – Isle of Man Airport Manx Marine Environmental Assessment Second Edition: October 2018 © Isle of Man Government, all rights reserved This document was produced as part of the Manx Marine Environmental Assessment, a Government project with external-stakeholder input, funded and facilitated by the Department of Infrastructure, Department for Enterprise and the Department of Environment, Food and Agriculture. This document is downloadable from the Department of Infrastructure website at: https://www.gov.im/about-the-government/departments/infrastructure/harbours- information/territorial-seas/manx-marine-environmental-assessment/ MMEA Contact: Manx Marine Environmental Assessment Fisheries Directorate Department of Environment, Food and Agriculture Thie Slieau Whallian Foxdale Road St John’s Isle of Man IM4 3AS Email: [email protected] Tel: 01624 685857 Suggested Citation: Reynolds A. 2018. Isle of Man Airport. In: Manx Marine Environmental Assessment (2nd Ed.). Isle of Man Government. 17 pp. Contributors to 1st edition: Paul Clarkson - Department of Infrastructure Sarah Corlett - Department of Infrastructure Laura Hanley* – formerly Department of Environment, Food and Agriculture Disclaimer: The Isle of Man Government has facilitated the compilation of this document, to provide baseline information on the Manx marine environment. Information has been provided by various Government Officers, marine experts, local organisations and industry, often in a voluntary capacity or outside their usual work remit. Advice should always be sought from relevant contacts where queries arise. -

How to Get Around the Isle of Man Public Transport

How to get around the Isle of Man Public Transport Let public transport take the strain while at the Isle of Man TT. Travel on the extensive bus network or hop on board the Victorian rail network, you’ll find getting around the island easy and cost-effective. Buses The island has an extensive bus network - Bus Vannin - which serves the whole of the island on a regular basis including the Isle of Man airport and the Sea Terminal in Douglas. An increased late night bus service operates on Friday and Saturday evenings which serves all the main towns. Buy a multi-journey ticket which will help you travel around the island. The 3, 5 or 7 day Explorer ticket allows unlimited travel on all scheduled railway services, the Douglas Horse Trams and most bus services. Tip : The bus service goes around the TT course from Douglas to Ramsey when the road is open, there is no access once the road is closed. No bus service travels along the mountain section from Ramsey to Douglas, but you can access the bungalow area using the mountain railway. Railway The Isle of Man boasts three heritage railways – the Manx Electric Railway, Steam Railway and Snaefell Mountain Railway – which will transport you to your chosen destination in style. The Electric railway travels from Douglas to Ramsey via Laxey, where you can also join the Snaefell Mountain Railway. You can take the Steam Railway from Douglas to Port Erin with stops in Castletown, Port St Mary amongst others. Tip: The Electric trams are not affected by the TT course being closed.