Larval Problems and Perspectives in Life

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Atlas of the Copepods (Class Crustacea: Subclass Copepoda: Orders Calanoida, Cyclopoida, and Harpacticoida)

Taxonomic Atlas of the Copepods (Class Crustacea: Subclass Copepoda: Orders Calanoida, Cyclopoida, and Harpacticoida) Recorded at the Old Woman Creek National Estuarine Research Reserve and State Nature Preserve, Ohio by Jakob A. Boehler and Kenneth A. Krieger National Center for Water Quality Research Heidelberg University Tiffin, Ohio, USA 44883 August 2012 Atlas of the Copepods, (Class Crustacea: Subclass Copepoda) Recorded at the Old Woman Creek National Estuarine Research Reserve and State Nature Preserve, Ohio Acknowledgments The authors are grateful for the funding for this project provided by Dr. David Klarer, Old Woman Creek National Estuarine Research Reserve. We appreciate the critical reviews of a draft of this atlas provided by David Klarer and Dr. Janet Reid. This work was funded under contract to Heidelberg University by the Ohio Department of Natural Resources. This publication was supported in part by Grant Number H50/CCH524266 from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The Old Woman Creek National Estuarine Research Reserve in Ohio is part of the National Estuarine Research Reserve System (NERRS), established by Section 315 of the Coastal Zone Management Act, as amended. Additional information about the system can be obtained from the Estuarine Reserves Division, Office of Ocean and Coastal Resource Management, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, U.S. Department of Commerce, 1305 East West Highway – N/ORM5, Silver Spring, MD 20910. Financial support for this publication was provided by a grant under the Federal Coastal Zone Management Act, administered by the Office of Ocean and Coastal Resource Management, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Silver Spring, MD. -

Oceanography and Marine Biology an Annual Review Volume 56

Oceanography and Marine Biology An Annual Review Volume 56 S.J. Hawkins, A.J. Evans, A.C. Dale, L.B. Firth & I.P. Smith First Published 2018 ISBN 978-1-138-31862-5 (hbk) ISBN 978-0-429-45445-5 (ebk) Chapter 5 Impacts and Environmental Risks of Oil Spills on Marine Invertebrates, Algae and Seagrass: A Global Review from an Australian Perspective John K. Keesing, Adam Gartner, Mark Westera, Graham J. Edgar, Joanne Myers, Nick J. Hardman-Mountford & Mark Bailey (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0) Oceanography and Marine Biology: An Annual Review, 2018, 56, 2-61 © S. J. Hawkins, A. J. Evans, A. C. Dale, L. B. Firth, and I. P. Smith, Editors Taylor & Francis IMPACTS AND ENVIRONMENTAL RISKS OF OIL SPILLS ON MARINE INVERTEBRATES, ALGAE AND SEAGRASS: A GLOBAL REVIEW FROM AN AUSTRALIAN PERSPECTIVE JOHN K. KEESING1,2*, ADAM GARTNER3, MARK WESTERA3, GRAHAM J. EDGAR4,5, JOANNE MYERS1, NICK J. HARDMAN-MOUNTFORD1,2 & MARK BAILEY3 1CSIRO Oceans and Atmosphere, Indian Ocean Marine Research Centre, M097, 35 Stirling Highway, Crawley, 6009, Australia 2University of Western Australia Oceans Institute, Indian Ocean Marine Research Centre, M097, 35 Stirling Highway, Crawley, 6009, Australia 3BMT Pty Ltd, PO Box 462, Wembley, 6913, Australia 4Aquenal Pty Ltd, 244 Summerleas Rd, Kingston, 7050, Australia 5Institute for Marine and Antarctic Studies, University of Tasmania, Private Bag 49, Hobart, 7001, Australia *Corresponding author: John K. Keesing e-mail: [email protected] Abstract Marine invertebrates and macrophytes are sensitive to the toxic effects of oil. Depending on the intensity, duration and circumstances of the exposure, they can suffer high levels of initial mortality together with prolonged sublethal effects that can act at individual, population and community levels. -

A New Type of Plankton Food Web Functioning in Coastal Waters Revealed by Coupling Monte Carlo Markov Chain Linear Inverse Metho

A new type of plankton food web functioning in coastal waters revealed by coupling Monte Carlo Markov Chain Linear Inverse method and Ecological Network Analysis Marouan Meddeb, Nathalie Niquil, Boutheina Grami, Kaouther Mejri, Matilda Haraldsson, Aurélie Chaalali, Olivier Pringault, Asma Sakka Hlaili To cite this version: Marouan Meddeb, Nathalie Niquil, Boutheina Grami, Kaouther Mejri, Matilda Haraldsson, et al.. A new type of plankton food web functioning in coastal waters revealed by coupling Monte Carlo Markov Chain Linear Inverse method and Ecological Network Analysis. Ecological Indicators, Elsevier, 2019, 104, pp.67-85. 10.1016/j.ecolind.2019.04.077. hal-02146355 HAL Id: hal-02146355 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02146355 Submitted on 3 Jun 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. 1 A new type of plankton food web functioning in coastal waters revealed by coupling 2 Monte Carlo Markov Chain Linear Inverse method and Ecological Network Analysis 3 4 5 Marouan Meddeba,b*, Nathalie Niquilc, Boutheïna Gramia,d, Kaouther Mejria,b, Matilda 6 Haraldssonc, Aurélie Chaalalic,e,f, Olivier Pringaultg, Asma Sakka Hlailia,b 7 8 aUniversité de Carthage, Faculté des Sciences de Bizerte, Laboratoire de phytoplanctonologie 9 7021 Zarzouna, Bizerte, Tunisie. -

Reported Siphonostomatoid Copepods Parasitic on Marine Fishes of Southern Africa

REPORTED SIPHONOSTOMATOID COPEPODS PARASITIC ON MARINE FISHES OF SOUTHERN AFRICA BY SUSAN M. DIPPENAAR1) School of Molecular and Life Sciences, University of Limpopo, Private Bag X1106, Sovenga 0727, South Africa ABSTRACT Worldwide there are more than 12000 species of copepods known, of which 4224 are symbiotic. Most of the symbiotic species belong to two orders, Poecilostomatoida (1771 species) and Siphonos- tomatoida (1840 species). The order Siphonostomatoida currently consists of 40 families that are mostly marine and infect invertebrates as well as vertebrates. In a report on the status of the marine biodiversity of South Africa, parasitic invertebrates were highlighted as taxa about which very little is known. A list was compiled of all the records of siphonostomatoids of marine fishes from southern African waters (from northern Angola along the Atlantic Ocean to northern Mozambique along the Indian Ocean, including the west coast of Madagascar and the Mozambique channel). Quite a few controversial reports exist that are discussed. The number of species recorded from southern African waters comprises a mere 9% of the known species. RÉSUMÉ Dans le monde, il y a plus de 12000 espèces de Copépodes connus, dont 4224 sont des symbiotes. La plupart de ces espèces symbiotes appartiennent à deux ordres, les Poecilostomatoida (1771 espèces) et les Siphonostomatoida (1840 espèces). L’ordre des Siphonostomatoida comprend actuellement 40 familles, qui sont pour la plupart marines, et qui infectent des invertébrés aussi bien que des vertébrés. Dans un rapport sur l’état de la biodiversité marine en Afrique du Sud, les invertébrés parasites ont été remarqués comme étant très peu connus. -

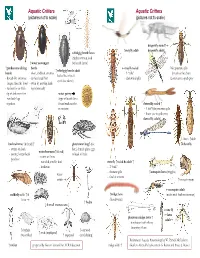

Aquatic Critters Aquatic Critters (Pictures Not to Scale) (Pictures Not to Scale)

Aquatic Critters Aquatic Critters (pictures not to scale) (pictures not to scale) dragonfly naiad↑ ↑ mayfly adult dragonfly adult↓ whirligig beetle larva (fairly common look ↑ water scavenger for beetle larvae) ↑ predaceous diving beetle mayfly naiad No apparent gills ↑ whirligig beetle adult beetle - short, clubbed antenna - 3 “tails” (breathes thru butt) - looks like it has 4 - thread-like antennae - surface head first - abdominal gills Lower jaw to grab prey eyes! (see above) longer than the head - swim by moving hind - surface for air with legs alternately tip of abdomen first water penny -row bklback legs (fbll(type of beetle larva together found under rocks damselfly naiad ↑ in streams - 3 leaf’-like posterior gills - lower jaw to grab prey damselfly adult↓ ←larva ↑adult backswimmer (& head) ↑ giant water bug↑ (toe dobsonfly - swims on back biter) female glues eggs water boatman↑(&head) - pointy, longer beak to back of male - swims on front -predator - rounded, smaller beak stonefly ↑naiad & adult ↑ -herbivore - 2 “tails” - thoracic gills ↑mosquito larva (wiggler) water - find in streams strider ↑mosquito pupa mosquito adult caddisfly adult ↑ & ↑midge larva (males with feather antennae) larva (bloodworm) ↑ hydra ↓ 4 small crustaceans ↓ crane fly ←larva phantom midge larva ↑ adult→ - translucent with silvery bflbuoyancy floats ↑ daphnia ↑ ostracod ↑ scud (amphipod) (water flea) ↑ copepod (seed shrimp) References: Aquatic Entomology by W. Patrick McCafferty ↑ rotifer prepared by Gwen Heistand for ACR Education midge adult ↑ Guide to Microlife by Kenneth G. Rainis and Bruce J. Russel 28 How do Aquatic Critters Get Their Air? Creeks are a lotic (flowing) systems as opposed to lentic (standing, i.e, pond) system. Look for … BREATHING IN AN AQUATIC ENVIRONMENT 1. -

Order HARPACTICOIDA Manual Versión Española

Revista IDE@ - SEA, nº 91B (30-06-2015): 1–12. ISSN 2386-7183 1 Ibero Diversidad Entomológica @ccesible www.sea-entomologia.org/IDE@ Class: Maxillopoda: Copepoda Order HARPACTICOIDA Manual Versión española CLASS MAXILLOPODA: SUBCLASS COPEPODA: Order Harpacticoida Maria José Caramujo CE3C – Centre for Ecology, Evolution and Environmental Changes, Faculdade de Ciências, Universidade de Lisboa, 1749-016 Lisboa, Portugal. [email protected] 1. Brief definition of the group and main diagnosing characters The Harpacticoida is one of the orders of the subclass Copepoda, and includes mainly free-living epibenthic aquatic organisms, although many species have successfully exploited other habitats, including semi-terrestial habitats and have established symbiotic relationships with other metazoans. Harpacticoids have a size range between 0.2 and 2.5 mm and have a podoplean morphology. This morphology is char- acterized by a body formed by several articulated segments, metameres or somites that form two separate regions; the anterior prosome and the posterior urosome. The division between the urosome and prosome may be present as a constriction in the more cylindric shaped harpacticoid families (e.g. Ectinosomatidae) or may be very pronounced in other familes (e.g. Tisbidae). The adults retain the central eye of the larval stages, with the exception of some underground species that lack visual organs. The harpacticoids have shorter first antennae, and relatively wider urosome than the copepods from other orders. The basic body plan of harpacticoids is more adapted to life in the benthic environment than in the pelagic environment i.e. they are more vermiform in shape than other copepods. Harpacticoida is a very diverse group of copepods both in terms of morphological diversity and in the species-richness of some of the families. -

Visceral and Cutaneous Larva Migrans PAUL C

Visceral and Cutaneous Larva Migrans PAUL C. BEAVER, Ph.D. AMONG ANIMALS in general there is a In the development of our concepts of larva II. wide variety of parasitic infections in migrans there have been four major steps. The which larval stages migrate through and some¬ first, of course, was the discovery by Kirby- times later reside in the tissues of the host with¬ Smith and his associates some 30 years ago of out developing into fully mature adults. When nematode larvae in the skin of patients with such parasites are found in human hosts, the creeping eruption in Jacksonville, Fla. (6). infection may be referred to as larva migrans This was followed immediately by experi¬ although definition of this term is becoming mental proof by numerous workers that the increasingly difficult. The organisms impli¬ larvae of A. braziliense readily penetrate the cated in infections of this type include certain human skin and produce severe, typical creep¬ species of arthropods, flatworms, and nema¬ ing eruption. todes, but more especially the nematodes. From a practical point of view these demon¬ As generally used, the term larva migrans strations were perhaps too conclusive in that refers particularly to the migration of dog and they encouraged the impression that A. brazil¬ cat hookworm larvae in the human skin (cu¬ iense was the only cause of creeping eruption, taneous larva migrans or creeping eruption) and detracted from equally conclusive demon¬ and the migration of dog and cat ascarids in strations that other species of nematode larvae the viscera (visceral larva migrans). In a still have the ability to produce similarly the pro¬ more restricted sense, the terms cutaneous larva gressive linear lesions characteristic of creep¬ migrans and visceral larva migrans are some¬ ing eruption. -

SSWIMS: Plankton

Unit Six SSWIMS/Plankton Unit VI Science Standards with Integrative Marine Science-SSWIMS On the cutting edge… This program is brought to you by SSWIMS, a thematic, interdisciplinary teacher training program based on the California State Science Content Standards. SSWIMS is provided by the University of California Los Angeles in collaboration with the Los Angeles County school districts, including the Los Angeles Unified School District. SSWIMS is funded by a major grant from the National Science Foundation. Plankton Lesson Objectives: Students will be able to do the following: • Determine a basis for plankton classification • Differentiate between various plankton groups • Compare and contrast plankton adaptations for buoyancy Key concepts: phytoplankton, zooplankton, density, diatoms, dinoflagellates, holoplankton, meroplankton Plankton Introduction “Plankton” is from a Greek word for food chains. They are autotrophs, “wanderer.” It is a making their own food, using the collective term for process of photosynthesis. The the various animal plankton or zooplankton eat organisms that drift or food for energy. These swim weakly in the heterotrophs feed on the open water of the sea or microscopic freshwater lakes and ponds. These world of the weak swimmers, carried about by sea and currents, range in size from the transfer tiniest microscopic organisms to energy up much larger animals such as the food jellyfish. pyramid to fishes, marine mammals, and humans. Plankton can be divided into two large groups: planktonic plants and Scientists are interested in studying planktonic animals. The plant plankton, because they are the basis plankton or phytoplankton are the for food webs in both marine and producers of ocean and freshwater freshwater ecosystems. -

Evolution of Direct-Developing Larvae: Selection Vs Loss Margaret Snoke Smith,1 Kirk S

Hypotheses Evolution of direct-developing larvae: selection vs loss Margaret Snoke Smith,1 Kirk S. Zigler,2 and Rudolf A. Raff1,3* Summary echinoderms, sea urchins, reveal that a majority of sea urchin Observations of a sea urchin larvae show that most species exhibit one of two life history strategies (Fig. 1).(10) species adopt one of two life history strategies. One strategy is to make numerous small eggs, which develop One strategy is to make many small eggs that develop into a into a larva with a required feeding period in the water larva that must feed and grow for weeks or months in the water column before metamorphosis. In contrast, the second column before metamorphosis. In the water column, these strategy is to make fewer large eggs with a larva that does larvae are dependent on plankton abundance for food and are not feed, which reduces the time to metamorphosis and subject to high levels of predation.(11) The other strategy thus the time spent in the water column. The larvae associated with each strategy have distinct morpholo- involves increasing egg size and maternal provisioning, which gies and developmental processes that reflect their decreases the reliance on planktonic food sources and the feeding requirements, so that those that feed exhibit time to metamorphosis, thus minimizing larval mortality. indirect development with a complex larva, and those that However, assuming finite resources for egg production, do not feed form a morphologically simplified larva and increasing egg size also reduces the total number of eggs exhibit direct development. Phylogenetic studies show that, in sea urchins, a feeding larva, the pluteus, is the produced. -

Hookworm-Related Cutaneous Larva Migrans

326 Hookworm-Related Cutaneous Larva Migrans Patrick Hochedez , MD , and Eric Caumes , MD Département des Maladies Infectieuses et Tropicales, Hôpital Pitié-Salpêtrière, Paris, France DOI: 10.1111/j.1708-8305.2007.00148.x Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/jtm/article/14/5/326/1808671 by guest on 27 September 2021 utaneous larva migrans (CLM) is the most fre- Risk factors for developing HrCLM have specifi - Cquent travel-associated skin disease of tropical cally been investigated in one outbreak in Canadian origin. 1,2 This dermatosis fi rst described as CLM by tourists: less frequent use of protective footwear Lee in 1874 was later attributed to the subcutane- while walking on the beach was signifi cantly associ- ous migration of Ancylostoma larvae by White and ated with a higher risk of developing the disease, Dove in 1929. 3,4 Since then, this skin disease has also with a risk ratio of 4. Moreover, affected patients been called creeping eruption, creeping verminous were somewhat younger than unaffected travelers dermatitis, sand worm eruption, or plumber ’ s itch, (36.9 vs 41.2 yr, p = 0.014). There was no correla- which adds to the confusion. It has been suggested tion between the reported amount of time spent on to name this disease hookworm-related cutaneous the beach and the risk of developing CLM. Consid- larva migrans (HrCLM).5 ering animals in the neighborhood, 90% of the Although frequent, this tropical dermatosis is travelers in that study reported seeing cats on the not suffi ciently well known by Western physicians, beach and around the hotel area, and only 1.5% and this can delay diagnosis and effective treatment. -

A Comparison of Copepoda (Order: Calanoida, Cyclopoida, Poecilostomatoida) Density in the Florida Current Off Fort Lauderdale, Florida

Nova Southeastern University NSUWorks HCNSO Student Theses and Dissertations HCNSO Student Work 6-1-2010 A Comparison of Copepoda (Order: Calanoida, Cyclopoida, Poecilostomatoida) Density in the Florida Current Off orF t Lauderdale, Florida Jessica L. Bostock Nova Southeastern University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://nsuworks.nova.edu/occ_stuetd Part of the Marine Biology Commons, and the Oceanography and Atmospheric Sciences and Meteorology Commons Share Feedback About This Item NSUWorks Citation Jessica L. Bostock. 2010. A Comparison of Copepoda (Order: Calanoida, Cyclopoida, Poecilostomatoida) Density in the Florida Current Off Fort Lauderdale, Florida. Master's thesis. Nova Southeastern University. Retrieved from NSUWorks, Oceanographic Center. (92) https://nsuworks.nova.edu/occ_stuetd/92. This Thesis is brought to you by the HCNSO Student Work at NSUWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in HCNSO Student Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of NSUWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Nova Southeastern University Oceanographic Center A Comparison of Copepoda (Order: Calanoida, Cyclopoida, Poecilostomatoida) Density in the Florida Current off Fort Lauderdale, Florida By Jessica L. Bostock Submitted to the Faculty of Nova Southeastern University Oceanographic Center in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science with a specialty in: Marine Biology Nova Southeastern University June 2010 1 Thesis of Jessica L. Bostock Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Masters of Science: Marine Biology Nova Southeastern University Oceanographic Center June 2010 Approved: Thesis Committee Major Professor :______________________________ Amy C. Hirons, Ph.D. Committee Member :___________________________ Alexander Soloviev, Ph.D. -

Benthic Macroinvertebrate Sampling

Benthic Macroinvertebrate Sampling Norton Basin, Little Bay, Grass Hassock Channel, and the Raunt Submitted to: The Port Authority of New York and New Jersey New York State Department of Environmental Conservation Submitted by: Barry A. Vittor & Associates, Inc. Kingston, NY February 2003 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 INTRODUCTION...............................................................................................1 2.0 STUDY AREA......................................................................................................3 2.1 Norton Basin........................................................................................................ 3 2.2 Little Bay ............................................................................................................. 3 2.3 Reference Areas.................................................................................................... 3 2.3.1 The Raunt .................................................................................................... 3 2.3.2 Grass Hassock Channel ............................................................................... 4 3.0 METHODS..........................................................................................................4 3.1 Benthic Grab Sampling......................................................................................... 4 4.0 RESULTS.............................................................................................................7 4.1 Benthic Macroinvertebrates................................................................................