Mage, Rose G. 2018 Dr

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annual Report Fy 2018 Human Frontier Science Program Organization

APRIL 2017 APRIL 2018 — MARCH 2019 ANNUAL REPORT FY 2018 HUMAN FRONTIER SCIENCE PROGRAM ORGANIZATION The Human Frontier Science Program Organization (HFSPO) is unique, supporting international collaboration to undertake innovative, risky, basic research at the frontier of the life sciences. Special emphasis is given to the support and training of independent young investigators, beginning at the postdoctoral level. The Program is implemented by an international organisation, supported financially by Australia, Canada, France, Germany, India, Italy, Japan, the Republic of Korea, New Zealand, Norway, Singapore, Switzerland, the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Nothern Ireland, the United States of America, and the European Commission. Since 1990, over 7000 researchers from more than 70 countries have been supported. Of these, 28 HFSP awardees have gone on to receive the Nobel Prize. 2 The following documents are available on the HFSP website www.hfsp.org: Joint Communiqués (Tokyo 1992, Washington 1997, Berlin 2002, Bern 2004, Ottawa 2007, Canberra 2010, Brussels 2013, London 2016): https://www.hfsp.org/about/governance/membership Statutes of the International Human Frontier Science Program Organization: https://www.hfsp.org/about/governance/hfspo-statutes Guidelines for the participation of new members in HFSPO: https://www.hfsp.org/about/governance/membership General reviews of the HFSP (1996, 2001, 2006-2007, 2010, 2018): https://www.hfsp.org/about/strategy/reviews Updated and previous lists of awards, including titles and abstracts: -

October 11, 1994, NIH Record, Vol. XLVI, No. 21

October l 1, 1994 Vol. XLVI No. 21 "Still U.S. Department of Health The Second and Human Services Best Thing About Payday" National Institutes of Health Dunbar To Give First Pittman Lecture, Oct. 26 By Sara Byars scientist recognized internarionally for A her pioneering work in contraceptive vaccines has been selected to deliver the first Margaret Pittman Lecture, a new NIH series chat honors outstanding women scientists. Dr. Bonnie S. Dunbar, professor of cell . :/ biology and obstetrics and gynecology at Baylor College of Medicine, will speak on "New ':'' .:' f ,; ... .. Fromiers in Reproductive Biology and I !- J ~ , • I , , ' f ., ' / , , Contraceptive Vaccines" at 3 p.m. on 0cc. 26 ' • /} : 4 t ., : in Masur Auditorium, Bldg. I 0 . ' ' . ! • ' I I I • Guiding che development of che Pittman • ' ' ,• ,: k'I I ' I lectureship series is the NIH women scientists J: • ! • •'I I It♦ l'- : ,4 • • •· ... / ;~ ~ advisory committee, a group char advises At the NIH Research Festival 1994 poster session, Dr. Lynn Hudson (r), chief. molecular genetics section scientific directors on matters pertaining co rhe ofNJNDS' Laboratory ofViral and Molecular Pathogenesis, stops by to view the work ofDr. Rosemary role of women scientists at NIH. Wong, one ofthe authors who works in NIDDK's Molemlar, Cellular and Endocrinology Branch. See This lectureship honors Or. Margaret additional coverage ofthe event on Pages 6-7. Pittman, rhe first woman co hold the position (See PITTMAN LECTURE, Page 2) NIGMS Reorganizes, Moves to Natcher Bldg. is month, che N acional Institute of General Medical Sciences is undergoing a reorganiza Vitetta Is NIAID's 1994 tion and a move to che new William H. -

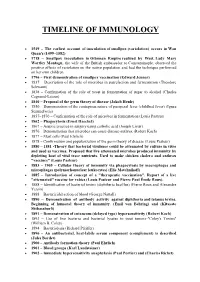

Timeline of Immunology

TIMELINE OF IMMUNOLOGY 1549 – The earliest account of inoculation of smallpox (variolation) occurs in Wan Quan's (1499–1582) 1718 – Smallpox inoculation in Ottoman Empire realized by West. Lady Mary Wortley Montagu, the wife of the British ambassador to Constantinople, observed the positive effects of variolation on the native population and had the technique performed on her own children. 1796 – First demonstration of smallpox vaccination (Edward Jenner) 1837 – Description of the role of microbes in putrefaction and fermentation (Theodore Schwann) 1838 – Confirmation of the role of yeast in fermentation of sugar to alcohol (Charles Cagniard-Latour) 1840 – Proposal of the germ theory of disease (Jakob Henle) 1850 – Demonstration of the contagious nature of puerperal fever (childbed fever) (Ignaz Semmelweis) 1857–1870 – Confirmation of the role of microbes in fermentation (Louis Pasteur) 1862 – Phagocytosis (Ernst Haeckel) 1867 – Aseptic practice in surgery using carbolic acid (Joseph Lister) 1876 – Demonstration that microbes can cause disease-anthrax (Robert Koch) 1877 – Mast cells (Paul Ehrlich) 1878 – Confirmation and popularization of the germ theory of disease (Louis Pasteur) 1880 – 1881 -Theory that bacterial virulence could be attenuated by culture in vitro and used as vaccines. Proposed that live attenuated microbes produced immunity by depleting host of vital trace nutrients. Used to make chicken cholera and anthrax "vaccines" (Louis Pasteur) 1883 – 1905 – Cellular theory of immunity via phagocytosis by macrophages and microphages (polymorhonuclear leukocytes) (Elie Metchnikoff) 1885 – Introduction of concept of a "therapeutic vaccination". Report of a live "attenuated" vaccine for rabies (Louis Pasteur and Pierre Paul Émile Roux). 1888 – Identification of bacterial toxins (diphtheria bacillus) (Pierre Roux and Alexandre Yersin) 1888 – Bactericidal action of blood (George Nuttall) 1890 – Demonstration of antibody activity against diphtheria and tetanus toxins. -

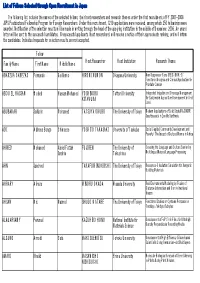

List of Fellows Selected Through Open Recruitment in Japan

List of Fellows Selected through Open Recruitment in Japan The following list includes the names of the selected fellows, their host researchers and research themes under the first recruitment of FY 2007-2008 JSPS Postdoctoral Fellowship Program for Foreign Researchers. Under this recruitment, 1219 applications were received, among which 250 fellowships were awarded. Notification of the selection results will be made in writing through the head of the applying institution in the middle of December, 2006. An award letter will be sent to the successful candidates. Unsuccessful applicants (host researchers) will receive a notice of their approximate ranking, and will inform the candidates. Individual requests for selection results are not accepted. Fellow Family Name First Name Middle Name Host Researcher Host Institution Research Theme ABARZUA CABEZAS Fernando Guillermo HIROMI KUMON Okayama University New Suppressor Gene (REIC/DKK-3): Functional Analysis and Clinical Application for Prostate Cancer ABOU EL HASSAN Waleed Hassan Mohamed YOSHINOBU Tottori University Integrated Irrigation and Drainage Management KITAMURA for Sustainable Agriculture Development in Arid Land ABUBAKAR Saifudin Mohamed TATSUYA OKUBO The University of Tokyo Modern Applications of Solid State MAS NMR Spectroscopy in Zeolite Synthesis ADI Alpheus Bongo Chimaeze YOSHITO TAKASAKI University of Tsukuba Social Capital, Community Development and Poverty: The Impact of Cultural Norms in Africa AHMED Mohamed Abdel Fattah FUJI REN The University of Crossing the Language and Culture Barrier by Ibrahim Tokushima Multilingual Natural Language Processing AHN Jaecheol TAKAFUMI NOGUCHI The University of Tokyo Resources-Circulation Simulation for Inorganic Building Materials AHRARY Alireza MINORU OKADA Waseda University Real Environments Modeling by Fusion of Distance Information and Omni-directional Images AHSAN Md. -

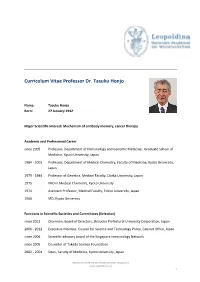

CV Tasuku Honjo

Curriculum Vitae Professor Dr. Tasuku Honjo Name: Tasuku Honjo Born: 27 January 1942 Major Scientific Interest: Mechanism of antibody memory, cancer therapy Academic and Professional Career since 2005 Professor, Department of Immunology and Genomic Medicine, Graduate School of Medicine, Kyoto University, Japan 1984 ‐ 2005 Professor, Department of Medical Chemistry, Faculty of Medicine, Kyoto University, Japan 1979 ‐ 1984 Professor of Genetics, Medical Faculty, Osaka University, Japan 1975 PHD in Medical Chemistry, Kyoto University 1974 Assistant Professor, Medical Faculty, Tokyo University, Japan 1966 MD, Kyoto University Functions in Scientific Societies and Committees (Selection) since 2012 Chairman, Board of Directors, Shizuoka Prefectural University Corporation, Japan 2006 ‐ 2012 Executive Member, Council for Science and Technology Policy, Cabinet Office, Japan since 2006 Scientific advisory board of the Singapore Immunology Network since 2005 Councilor of Takeda Science Foundation 2002 ‐ 2004 Dean, Faculty of Medicine, Kyoto University, Japan Nationale Akademie der Wissenschaften Leopoldina www.leopoldina.org 1 1996 ‐ 2000 Dean, Faculty of Medicine, Kyoto University, Japan since 1996 External advisory board of the Committee for Human Gene Therapy Working Group 1992 ‐ 1995 Fellowship review committee member of International Human Frontier Science Program Honours and Awarded Memberships (Selection) 2018 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 2016 Kyoto Prize 2012 Robert Koch Prize 2005 Member of Japan Academy 2004 Leading Japanese Scientists -

Recent Winners of the Nobel Medicine Prize 1 October 2018

Recent winners of the Nobel Medicine Prize 1 October 2018 2015: William Campbell (US citizen born in Ireland) and Satoshi Omura (Japan), Tu Youyou (China) for unlocking treatments for malaria and roundworm. 2014: John O'Keefe (Britain, US), Edvard I. Moser and May-Britt Moser (Norway) for discovering how the brain navigates with an "inner GPS". 2013: Thomas C. Suedhof (US citizen born in Germany), James E. Rothman and Randy W. Schekman (US) for work on how the cell organises its transport system. 2012: Shinya Yamanaka (Japan) and John B. Gurdon (Britain) for discoveries showing how adult cells can be transformed back into stem cells. 2011: Bruce Beutler (US), Jules Hoffmann (French citizen born in Luxembourg) and Ralph Steinman (Canada) for work on the body's immune system. Credit: Wikipedia 2010: Robert G. Edwards (Britain) for the development of in-vitro fertilisation. 2009: Elizabeth Blackburn (Australia-US), Carol Here is a list of the winners of the Nobel Medicine Greider and Jack Szostak (US) for discovering how Prize in the past 10 years, after James Allison of chromosomes are protected by telomeres, a key the US and Tasuku Honjo of Japan were awarded factor in the ageing process. Monday for research that has revolutionised cancer treatment: © 2018 AFP 2018: Immunologists Allison and Honjo win for figuring out how to release the immune system's brakes to allow it to attack cancer cells more efficiently. 2017: US geneticists Jeffrey Hall, Michael Rosbash and Michael Young for their discoveries on the internal biological clock that governs the wake- sleep cycles of most living things. -

The24th Keio Medical Science Prize

The 24th Keio Medical Science Prize Prize Laureates 1996 Stanley B. Prusiner, Shigetada Nakanishi 1997 Robert A. Weinberg, Tadatsugu Taniguchi 1998 M. Judah Folkman, Katsuhiko Mikoshiba 1999 Elizabeth H. Blackburn, Shinya Yoshikawa 2000 Arnold J. Levine, Yusuke Nakamura 2001 Tony Hunter, Masatoshi Takeichi 2002 Barry J. Marshall, Koichi Tanaka 2003 Ronald M. Evans, Yasushi Miyashita 2004 Roger Y. Tsien 2005 Yoshinori Fujiyoshi 2006 Thomas A. Steitz 2007 Brian J. Druker, Hiroaki Mitsuya 2008 Fred H. Gage, Shimon Sakaguchi 2009 Jeffrey M. Friedman, Kenji Kangawa 2010 Jules A. Hoffmann, Shizuo Akira 2011 Philip A. Beachy, Keiji Tanaka 2012 Steven A. Rosenberg, Hiroyuki Mano 2013 Victor R. Ambros, Shigekazu Nagata 2014 Karl Deisseroth, Hiroshi Hamada 2015 Jeffrey I. Gordon, Yoshinori Ohsumi 2016 Svante Pääbo, Tasuku Honjo 2017 John E. Dick, Seiji Ogawa 2018 Feng Zhang, Masashi Yanagisawa Deadline: Thursday, March 7, 2019 (Japan local time) Keio University annually awards The Keio Medical Science Prize to recognize researchers who have made an outstanding contribution to the field of medicine and life sciences. Laureates receive a certificate of merit, medal, and a monetary award of 10 million yen. The award ceremony and commemorative lectures are held at Keio University in Tokyo, Japan. 〈Criteria〉 - A researcher who have made a breakthrough in the fields of medicine and life sciences, or a Call related field. - A researcher who have made an outstanding contribution to basic and clinical medicine. 〈Selection〉 13 selection committee members and around 80 specialists from various fields within and outside for Keio University will select laureates through a rigorous review process. 〈Eligibility〉 Nominees must be currently active in their field of research, and be expected to make future contributions to the field. -

Tasuku Honjo Kyoto University, Kyoto, Japan

333 Serendipities of Acquired Immunity Nobel Lecture, December 7, 2018 by Tasuku Honjo Kyoto University, Kyoto, Japan. INTRODUCTION For a long time, biology was perceived as the lesser of the natural sciences because, unlike physics, deductive reasoning could not be used to solve biological problems. Biology has been full of mystery since I started my career in biological sciences almost half a century ago. Although the basic principles of biology stem from the rules of physics, biological systems have such an extraordinary, layered complexity derived from a tremen- dous number of parameters, beautifully and magically intertwined and controlled to achieve what we call “life”. Paradoxically, we start with a rather limited number (about 20,000) of coding region genes. However, many transcripts can be generated from a single coding gene locus, indi- cating that a single gene can produce many proteins. Furthermore, there are a much higher number of non-coding transcripts that may afect the expression of the coding genes. DNA, RNA and proteins can be chemically modifed by methylation, phosphorylation and acetylation. In addition, at least 20,000 metabolites circulate in our blood. These can also be sensed by cells, interacting with various proteins and infuencing gene expres- sion, thus generating enormously complicated regulatory mechanisms to achieve homeostasis. The origin of metabolites can be traced not only to the biochemistry of our own cells but also to the diverse communities of 334 THE NOBEL PRIZES microbes inhabiting every surface of the body. If we imagine roughly 1013 order of our own cells, each expressing diferent proteins and containing diferent metabolites, in constant dialog with 1014 order of microbial cells, also in diferent metabolic states, the complexity of our biological system exceeds by far the physical and chemical complexity of the universe. -

Programme 70Th Lindau Nobel Laureate Meeting 27 June - 2 July 2021

70 Programme 70th Lindau Nobel Laureate Meeting 27 June - 2 July 2021 Sessions Speakers Access Background Scientific sessions, Nobel Laureates, Clear guidance Everything else social functions, young scientists, to all viewing there is to know partner events, invited experts, and participation for a successful networking breaks moderators options meeting 2 Welcome Two months ago, everything was well on course to celebrate And yet: this interdisciplinary our 70th anniversary with you, in Lindau. anniversary meeting will feature But with the safety and health of all our participants being the most rich and versatile programme ever. of paramount importance, we were left with only one choice: It will provide plenty of opportunity to educate, inspire, go online. connect – and to celebrate! Join us. 4 PARTICIPATING LAUREATES 4 PARTICIPATING LAUREATES 5 Henry A. Joachim Donna George P. Hartmut Michael M. Adam Hiroshi Kissinger Frank Strickland Smith Michel Rosbash Riess Amano Jeffrey A. Peter Richard R. James P. Randy W. Brian K. Barry C. Dean Agre Schrock Allison Schekman Kobilka Barish John L. Harvey J. Robert H. J. Michael Martin J. Hall Alter Grubbs Kosterlitz Evans F. Duncan David J. Ben L. Edmond H. Carlo Brian P. Kailash Elizabeth Haldane Gross Feringa Fischer Rubbia Schmidt Satyarthi Blackburn Robert B. Reinhard Aaron Walter Barry J. Harald Takaaki Laughlin Genzel Ciechanover Gilbert Marshall zur Hausen Kajita Christiane Serge Steven Françoise Didier Martin Nüsslein- Haroche Chu Barré-Sinoussi Queloz Chalfie Volhard Anthony J. Gregg L. Robert J. Saul Klaus William G. Leggett Semenza Lefkowitz Perlmutter von Klitzing Kaelin Jr. Stefan W. Thomas C. Emmanuelle Kurt Ada Konstantin S. -

Press Release ENGLISH (PDF)

The Nobel Assembly at Karolinska Institutet has today decided to award the 2018 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine jointly to James P. Allison and Tasuku Honjo for their discovery of cancer therapy by inhibition of negative immune regulation SUMMARY Cancer kills millions of people every year and is one of humanity’s greatest health challenges. By stimulating the inherent ability of our immune system to attack tumor cells this year’s Nobel Laureates have established an entirely new principle for cancer therapy. James P. Allison studied a known protein that functions as a brake on the immune system. He realized the potential of releasing the brake and thereby unleashing our immune cells to attack tumors. He then developed this concept into a brand new approach for treating patients. In parallel, Tasuku Honjo discovered a protein on immune cells and, after careful exploration of its function, eventually revealed that it also operates as a brake, but with a different mechanism of action. Therapies based on his discovery proved to be strikingly effective in the fight against cancer. Allison and Honjo showed how different strategies for inhibiting the brakes on the immune system can be used in the treatment of cancer. The seminal discoveries by the two Laureates constitute a landmark in our fight against cancer. 1 Can our immune defense be engaged for cancer treatment? Cancer comprises many different diseases, all characterized by uncontrolled proliferation of abnormal cells with capacity for spread to healthy organs and tissues. A number of therapeutic approaches are available for cancer treatment, including surgery, radiation, and other strategies, some of which have been awarded previous Nobel Prizes. -

Contributions of Civilizations to International Prizes

CONTRIBUTIONS OF CIVILIZATIONS TO INTERNATIONAL PRIZES Split of Nobel prizes and Fields medals by civilization : PHYSICS .......................................................................................................................................................................... 1 CHEMISTRY .................................................................................................................................................................... 2 PHYSIOLOGY / MEDECINE .............................................................................................................................................. 3 LITERATURE ................................................................................................................................................................... 4 ECONOMY ...................................................................................................................................................................... 5 MATHEMATICS (Fields) .................................................................................................................................................. 5 PHYSICS Occidental / Judeo-christian (198) Alekseï Abrikossov / Zhores Alferov / Hannes Alfvén / Eric Allin Cornell / Luis Walter Alvarez / Carl David Anderson / Philip Warren Anderson / EdWard Victor Appleton / ArthUr Ashkin / John Bardeen / Barry C. Barish / Nikolay Basov / Henri BecqUerel / Johannes Georg Bednorz / Hans Bethe / Gerd Binnig / Patrick Blackett / Felix Bloch / Nicolaas Bloembergen -

Cbnå“Rresearch VOLUME 48 €¢NUMBER17 €¢Cnrea8•PP4719-5064

CbnœrResearch VOLUME 48 •NUMBER17 •CNREA8•PP4719-5064 CONTENTSf Asterisks # preceding page numbers refer to studies using human-derived material. BASIC SCIENCES 4790 Effect of Dietary Eicosapentaenoic Acid on Azoxymethane- induced Colon Carcinogenesis in Rats. Toshiyuki Minoura, $4719 Antagonism of Voltage-gated Calcium Channels in Small Cell Toshiyuki Takata, Michitomo Sakaguchi, Hideho Takada, Carcinomas of Patients with and without Lambert-Eaton My Manabu Yamamura, Koshiro Hioki, and Masakatsu Yamamoto. asthenie Syndrome by Autoantibodies w-Conotoxin and Ade- 4795 Isolation and Characterization of a Complementary DNA Clone nosine. Henry J. De Aizpurua, Edward H. Lambert, Guy E. for a \1, 32,000 Protein Which Is Induced with Tumor Promoters Griesmann, Baldomero M. Olivera, and Vanda A. Lennon. in BALB/c 3T3 Cells. Hajime Kageyama, Takaki Hiwasa, Katsuo Tokunaga, and Shigeru Sakiyama. 4725 Delivery of Melanoma-associated Immunoglobulin Monoclonal Antibody and Fab Fragments to Normal Brain Utilizing Osmotic 4799 Selective Modulation of Antibody Response and Natural Killer Blood-Brain Barrier Disruption. Edward A. Neuwelt, Peggy A. Cell Activity by l'uri in- Nucleoside Analogues. Teresa Priebe, Barnett, I. Hellström, K. E. Hellström, Paul Beaumier, Osama Kandil, Melila Nakic, Bih Fang Pan. and J. Arly Nelson. Christopher I. McCormick, and Ronald M. Weigel. 4804 Formation of Interstrand Cross-Links in Chloroacetaldehyde- 4730 Augmentation of Tumor Targeting in a Line of Glioma-specific treated DNA Demonstrated by Ethidium Bromide Fluorescence. Mouse Cytotoxic T-Lymphocytes by Retroviral Expression of S. J. Spengler and B. Singer. Mouse •Y-InterferonComplementary DNA. Kiyoshi Nishihara. 4807 Curative Effect of DL-2-Difluoromethylornithine in Mice Bearing Shinichi Miyatake, Tsuneaki Sakata, Junkoh Yamashita, Mutant I 1210 Leukemia Cells Deficient in Polyamine Uptake.