Historical Attempts to Reorganize the Reserve Components

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Defense Primer: Reserve Forces

Updated January 28, 2021 Defense Primer: Reserve Forces The term reserve component (RC) refers collectively to the passes from the governor of the affected units and seven individual reserve components of the Armed Forces. personnel to the President of the United States. Congress exercises authority over the reserve components under its constitutional authority “to raise and support Reserve Categories Armies,” “to provide and maintain a Navy,” and “to All reservists, whether they are in the Reserves or the provide for organizing, arming, and disciplining the National Guard, are assigned to one of three major reserve Militia.... ” (Article I, Section 8) categories: the Ready Reserve, the Standby Reserve, or the Retired Reserve. There are seven reserve components: Ready Reserve Army National Guard The Ready Reserve is the primary manpower pool of the reserve components. Members of the Ready Reserve will Army Reserve usually be called to active duty before members of the Standby Reserve or the Retired Reserve. The Ready Navy Reserve Reserve is made up of three subcomponents: Marine Corps Reserve The Selected Reserve contains those units and individuals within the Ready Reserve designated as “so Air National Guard essential to initial wartime missions that they have priority over all other Reserves.” (DOD Instruction Air Force Reserve 1215.06.) Members of the Selected Reserve are generally required to perform one weekend of training Coast Guard Reserve each month and two weeks of training each year, although some may train more than this. When The purpose of these seven reserve components, as codified reservists are activated, they most frequently come from in law, is to “provide trained units and qualified persons this category. -

Inside the News

News. Society of National Association Publications - Award Winning Newspaper Published by the Association of the U.S. Army VOLUME 42 NUMBER 2 www.ausa.org December 2018 Inside the News 2018 Annual Meeting Award Presentations – 9, 12 to 16 – New Army Uniform – 2 – Piggee on Logistics – 2 – AUSA Family Readiness Building a Battle Plan – 3 – AUSA Book Program Secret War in Laos – 6 – Capitol Focus New Army Vets in Congress – 10 – Future Vertical Lift – 10 – Synthetic Training Environment – 21 – Chapter Highlights Redstone-Huntsville 3 NCOs Honored – 18 – Charleston VA Nurse Honored – 21 – Sniper teams from across the globe travelled to Fort Benning, Ga., to compete Robert E. Lee in the Annual International Sniper Competition. The goal of this competition Vietnam War Anniversary is to identify the best sniper team from a wide range of agencies and organiza- – 22 – tions that includes the U.S. military, international militaries, and local, state and federal law enforcement. (Photo by Master Sgt. Michel Sauret) Redstone-Huntsville The Wall That Heals See NCO Report on Page 8 – 24 – 2 AUSA NEWS q December 2018 ASSOCIATION OF THE UNITED STATES ARMY Piggee: Command maintenance, supply discipline are essential AUSA Staff In the past two years, the Army has regained its footing with improvements in the supply of spare he Army’s ability to sustain itself in an aus- parts across the Army and standardized brigade tere environment against a capable adversary combat team supply stockage, which has resulted in Twill depend on leveraging today’s technol- more weapon system repairs in forward locations. ogy more quickly, the Army’s chief logistician says. -

The United States Atomic Army, 1956-1960 Dissertation

INTIMIDATING THE WORLD: THE UNITED STATES ATOMIC ARMY, 1956-1960 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Paul C. Jussel, B.A., M.M.A.S., M.S.S. * * * * * The Ohio State University 2004 Dissertation Committee Approved by Professor Allan R. Millett, Advisor Professor John R. Guilmartin __________________ Professor William R. Childs Advisor Department of History ABSTRACT The atomic bomb created a new military dynamic for the world in 1945. The bomb, if used properly, could replace the artillery fires and air-delivered bombs used to defeat the concentrated force of an enemy. The weapon provided the U.S. with an unparalleled advantage over the rest of the world, until the Soviet Union developed its own bomb by 1949 and symmetry in warfare returned. Soon, theories of warfare changed to reflect the belief that the best way to avoid the effects of the bomb was through dispersion of forces. Eventually, the American Army reorganized its divisions from the traditional three-unit organization to a new five-unit organization, dubbed pentomic by its Chief of Staff, General Maxwell D. Taylor. While atomic weapons certainly had an effect on Taylor’s reasoning to adopt the pentomic organization, the idea was not new in 1956; the Army hierarchy had been wrestling with restructuring since the end of World War II. Though the Korean War derailed the Army’s plans for the early fifties, it returned to the forefront under the Eisenhower Administration. The driving force behind reorganization in 1952 was not ii only the reoriented and reduced defense budget, but also the Army’s inroads to the atomic club, formerly the domain of only the Air Force and the Navy. -

Exiting Requires More Than a Thought

MANAGEMENTSOLUTIONS Exiting Requires More than a Thought By Preston Ingalls “Life is a succession of lessons which must be lived to HOW SUCCESSION PLAYS OUT IN BUSINESS be understood. All is riddle, and the key to a riddle is Business owners will go to great lengths to put policies another riddle.” Ralph Waldo Emerson and procedures in place to ensure day-to-day operations run smoothly. They see the value of having standardized n June 1968, General William Westmoreland was processes to prevent variation in methods. These same relieved of his command in Vietnam when his new owners will develop 3- to 5-year plans to prepare and I boss, Richard Nixon, lost confidence in his approach. sustain growth in their businesses. His second in command, General Creighton Abrams, was However, many procrastinate developing an exit strategy. suddenly thrust in command. Abrams was a WWII hero at As key players, owners and stakeholders, we all want to Bastogne and was well respected by the rank and file. believe we are somewhat indispensable and a critical Abrams immediately switched from Westmoreland’s failed lifeline to the enterprise. But that dependency can create “Search and Destroy” strategy, put in place in the early a weakness and vulnerability. After all, we are all mortal. 60’s, and moved to the more successful counterinsurgency. We plan to retire someday. As we age, we are subject to General Fred Weyand said, “The tactics changed prolonged illness. Despite these possibilities, we prefer within 15 minutes of Abrams’s taking command.” The not to consider the eventual exodus from the business, unassuming Abrams was in sharp contrast to the flamboyant retirement, disability, passing on, or some other cause. -

Officer Candidate Guide US Army National Guard

Officer Candidate Guide May 2011 Officer Candidate Guide US Army National Guard May 2011 Officer Candidate Guide May 2011 Officer Candidate School, Reserve Component Summary. This pamphlet provides a guide for US Army National Guard Officer Candidate School students and cadre. Proponent and exception authority. The proponent of this pamphlet is the Commanding General, US Army Infantry School. The CG, USAIS has the authority to approve exceptions to this pamphlet that are consistent with controlling laws and regulations. The CG, USAIS may delegate this authority, in writing, to a division chief within the proponent agency in the grade of Colonel or the civilian equivalent. Intent. The intent of this pamphlet is to ensure that National Guard OCS Candidates nationwide share one common standard. It facilitates the cross-state and cross-TASS region boundary training of US Army officer candidates. Use of the term “States”. Unless otherwise stated, whenever the term “States” is used, it is referring to the CONUS States, Alaska, Hawaii, the US Virgin Islands, Territory of Guam, the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico, and District of Columbia. Supplementation. Local OCS programs may supplement this document in order to meet the needs of local SOPs and regulations, but they may not substantially modify any policy set forth in this document without written authorization from the proponent. Suggested improvements. Users are invited to send comments and suggested improvements on DA Form 2028 (Recommended Changes to Publications and Blank Forms) directly to the OCS SME, 200th Regiment, Fort McClellan, Alabama 36205. Distribution. This publication is available in electronic media only and is intended for all Reserve Component OCS cadre and students. -

January and February

VIETNAM VETERANS OF AMERICA Office of the National Chaplain FOUAD KHALIL AIDE -- Funeral service for Major Fouad Khalil Aide, United States Army (Retired), 78, will be Friday, November 13, 2009, at 7 p.m. at the K.L. Brown Funeral Home and Cremation Center Chapel with Larry Amerson, Ken Rollins, and Lt. Col. Don Hull officiating, with full military honors. The family will receive friends Friday evening from 6-7 p.m. at the funeral home. Major Aide died Friday, November 6, 2009, in Jacksonville Alabama. The cause of death was a heart attack. He is survived by his wife, Kathryn Aide, of Jacksonville; two daughters, Barbara Sifuentes, of Carrollton, Texas, and Linda D'Anzi, of Brighton, England; two sons, Lewis Aide, of Columbia, Maryland, and Daniel Aide, of Springfield, Virginia, and six grandchildren. Pallbearers will be military. Honorary pallbearers will be Ken Rollins, Matt Pepe, Lt. Col. Don Hull, Jim Hibbitts, Jim Allen, Dan Aide, Lewis Aide, VVA Chapter 502, and The Fraternal Order of Police Lodge. Fouad was commissioned from the University of Texas ROTC Program in 1953. He served as a Military Police Officer for his 20 years in the Army. He served three tours of duty in Vietnam, with one year as an Infantry Officer. He was recalled to active duty for service in Desert Shield/Desert Storm. He was attached to the FBI on their Terrorism Task Force because of his expertise in the various Arabic dialects and cultures. He was fluent in Arabic, Spanish and Vietnamese and had a good working knowledge of Italian, Portuguese and French. -

Nixon's Communications Strategy After Lam Son

Chapman University Chapman University Digital Commons War and Society (MA) Theses Dissertations and Theses Winter 12-9-2019 Stop Talking about Sorrow: Nixon’s Communications Strategy after Lam Son 719 Dominic K. So Chapman University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.chapman.edu/war_and_society_theses Part of the Military History Commons, Political History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation So, Dominic K. Stop Talking about Sorrow: Nixon’s Communications Strategy after Lam Son 719. 2019. Chapman University, MA Thesis. Chapman University Digital Commons, https://doi.org/10.36837/ chapman.000102 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Dissertations and Theses at Chapman University Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in War and Society (MA) Theses by an authorized administrator of Chapman University Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Stop Talking about Sorrow: Nixon’s Communications Strategy after Lam Son 719 A Thesis by Dominic K. So Chapman University Orange, CA Wilkinson College of Arts, Humanities, and Social Sciences Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in War and Society Studies December 2019 Committee in charge: Gregory Daddis, Ph.D., Chair Lori Cox Han, Ph.D. Robert Slayton, Ph.D. The thesis of Dominic K. So is approved dis, Ph.D., Chair Lori Cox Han, Slayton, Ph.D December 2019 Stop Talking about Sorrow: Nixon’s Communications Strategy after Lam Son 719 Copyright © 2019 by Dominic K. So III ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Firstly, thank you to my advisor, Dr. -

First Michigan Volunteer Infantry Regiment (Three Months) Receiving Its Colors from the Ladies of Detroit

First Michigan – Three Months Volunteer Infantry Regiment “Thank God for Michigan!” It is confidently expected that the patriotic citizen soldiery of Michigan will promptly come forward to enlist in the cause of the Union, against which an extensive rebellion in arms exists, threatening the integrity and perpetuity of the government.1 Governor and Commander-in-Chief Austin Blair April 16, 1861 On April 12, 1861, the first guns of the Civil War were fired on Fort Sumter. On April 15, Governor Austin only three days later, Lincoln appealed to the “loyal” states for help in putting down the Blair rebellion, calling for 75,000 volunteers to serve for three months.2 Governor Austin Blair received the War Department’s telegram at his home in Jackson, advising him of Lincoln’s call to arms and informing him of Michigan’s quota: one regiment consisting of ten companies, or about 1,000 men. Governor Blair immediately left for Detroit to confer with the state’s Adjutant General, John Robertson.3 The problem: how to recruit, organize, arm, equip and train a regiment as quickly as possible. There were no funds for such an undertaking. Michigan’s treasury in 1861 was nearly depleted. Prominent business and civic leaders around the state stepped forward, pledging $80,000 in loans to get Michigan’s war effort started.4 On April 16, one day after receiving the War Department’s telegram, Governor Blair called for volunteers. The response was wildly enthusiastic, marked by a massive war Adjutant General John Robertson 1 First Michigan – Three Months Volunteer Infantry Regiment Ypsilanti Light Guard, the Marshall Light Guard and the Hardee Cadets— rendezvoused at Fort Wayne to drill and train.7 Colonel Frank W. -

BOOK REVIEW: the Generals

BOOK REVIEWS end simply is wearing stars, not leading of the institution and concerns over the the military properly into the next century senior leader’s career compete for consider- and candidly rendering their best military ation in the decision space. In an effort to advice to our nation’s civilian leaders. demonstrate an example of “doing it right” Ricks convincingly traces modern in the modern era, Ricks reaches deep failures of generalship to their origins below the senior-leader level to examine in the interwar period, through World the relief of Colonel Joe Dowdy, USMC, War II, Korea, Vietnam, and Operations the commander of First Marine Regiment Desert Storm, Iraqi Freedom, and Enduring in the march to Baghdad. Dowdy’s (not Freedom. He juxtaposes successful Army uncontroversial) relief demonstrates that and Marine generals through their histories there is no indispensable man, and if a com- with the characteristics of history’s failed mander loses confidence in a subordinate, generals. Ricks draws specific, substanti- the subordinate must go. In Ricks’s view, if The Generals: American Military ated conclusions about generalship, Army it is a close call, senior leaders should err on Command from World War II to Today culture, civil-military relations, and the the side of relief: the human and strategic By Thomas E. Ricks way the Army has elected to organize, train, costs of getting that call wrong are virtually Penguin Press, 2012 and equip itself in ways that ultimately unconscionable. Ricks rightly concludes 576 pp. $32.95 suboptimized Service performance. Specifi- that too much emphasis has been placed ISBN: 978-1-59420-404-3 cally identifying the Army’s modern-era on the “career consequence” of relief for reluctance to effect senior leader reliefs as individual officers. -

THE WAY of the SOLDIER: REMEMBERING GENERAL CREIGHTON ABRAMS by Lewis Sorley

June 2012 June 2013 THE WAY OF THE SOLDIER: REMEMBERING GENERAL CREIGHTON ABRAMS By Lewis Sorley Lewis Sorley is the author of Thunderbolt: General Creighton Abrams and the Army of His Times and of A Better War: The Unexamined Victories and Final Tragedy of America’s Last Years in Vietnam. This essay is based on a lecture for FPRI’s Butcher History Institute conference on “Great Captains in American History,” the eighth weekend-long program for high school teachers on American military history hosted and cosponsored by the First Division Museum at Cantigny in Wheaton, Illinois ( a division of the McCormick Foundation) on April 20-21, 2013. The conference was supported by grants from the Butcher Family Foundation, the Lynde and Harry Bradley Foundation, and the Stuart Family Foundation. Creighton Abrams was something quite rare in the military profession, a man of tactical and strategic brilliance, personal bravery and integrity of the highest order, and inspiring leadership who was also compassionate, modest and wise. For nearly four decades, in three wars and in what passed for “peacetime” service in the interstices, he demonstrated the abundance of those qualities that made him a legend in his profession. As some of you may know, I have literally filled volumes chronicling the life and career of General Abrams. Today I want to provide an overview to illustrate what I view as his most important and consistent attributes, the things that set him apart and made him a great leader. Thus I will concentrate on his modesty and selflessness, his love of the soldier, his physical and moral courage, his vision, his ability to inspire and lead others, and his absolute and unshakeable integrity. -

Main Command Post-Operational Detachments

C O R P O R A T I O N Main Command Post- Operational Detachments (MCP-ODs) and Division Headquarters Readiness Stephen Dalzell, Christopher M. Schnaubelt, Michael E. Linick, Timothy R. Gulden, Lisa Pelled Colabella, Susan G. Straus, James Sladden, Rebecca Jensen, Matthew Olson, Amy Grace Donohue, Jaime L. Hastings, Hilary A. Reininger, Penelope Speed For more information on this publication, visit www.rand.org/t/RR2615 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available for this publication. ISBN: 978-1-9774-0225-7 Published by the RAND Corporation, Santa Monica, Calif. © Copyright 2019 RAND Corporation R® is a registered trademark. Limited Print and Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law. This representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for noncommercial use only. Unauthorized posting of this publication online is prohibited. Permission is given to duplicate this document for personal use only, as long as it is unaltered and complete. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of its research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please visit www.rand.org/pubs/permissions. The RAND Corporation is a research organization that develops solutions to public policy challenges to help make communities throughout the world safer and more secure, healthier and more prosperous. RAND is nonprofit, nonpartisan, and committed to the public interest. RAND’s publications do not necessarily reflect the opinions of its research clients and sponsors. Support RAND Make a tax-deductible charitable contribution at www.rand.org/giving/contribute www.rand.org Preface This report documents research and analysis conducted as part of a project entitled Multi- Component Units and Division Headquarters Readiness sponsored by U.S. -

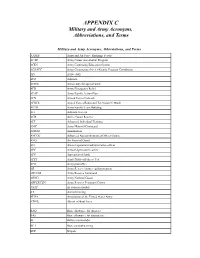

Military and Army Acronyms, Abbreviations, and Terms

APPENDIX C Military and Army Acronyms, Abbreviations, and Terms Military and Army Acronyms, Abbreviations, and Terms AAFES Army and Air Force Exchange Service ACAP Army Career and Alumni Program ACES Army Continuing Education System ACS/FPC Army Community Service/Family Program Coordinator AD Active duty ADJ Adjutant ADSW Active duty for special work AER Army Emergency Relief AFAP Army Family Action Plan AFN Armed Forces Network AFRTS Armed Forces Radio and Television Network AFTB Army Family Team Building AG Adjutant General AGR Active Guard Reserve AIT Advanced Individual Training AMC Army Materiel Command AMMO Ammunition ANCOC Advanced Noncommissioned Officer Course ANG Air National Guard AO Area of operations/administrative officer APC Armored personnel carrier APF Appropriated funds APFT Army Physical Fitness Test APO Army post office AR Army Reserve/Army regulation/armor ARCOM Army Reserve Command ARNG Army National Guard ARPERCEN Army Reserve Personnel Center ASAP As soon as possible AT Annual training AUSA Association of the United States Army AWOL Absent without leave BAQ Basic allowance for quarters BAS Basic allowance for subsistence BC Battery commander BCT Basic combat training BDE Brigade Military and Army Acronyms, Abbreviations, and Terms cont’d BDU Battle dress uniform (jungle, desert, cold weather) BN Battalion BNCOC Basic Noncommissioned Officer Course CAR Chief of Army Reserve CASCOM Combined Arms Support Command CDR Commander CDS Child Development Services CG Commanding General CGSC Command and General Staff College