Title: Migrating Children, Households, and the Post-Socialist State: An

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Islam at the Margins: the Muslims of Indochina

CIAS Discussion Paper No.3 Islam at the Margins: The Muslims of Indochina Edited by OMAR FAROUK Hiroyuki YAMAMOTO 2008 Center for Integrated Area Studies, Kyoto University Kyoto, Japan Islam at the Margins: The Muslims of Indochina 1 Contents Preface ……………………………………………………………………3 Hiroyuki YAMAMOTO Introduction ……………………………………………………………...5 OMAR FAROUK The Cham Muslims in Ninh Thuan Province, Vietnam ………………7 Rie NAKAMURA Bani Islam Cham in Vietnam ………………………………………….24 Ba Trung PHU The Baweans of Ho Chi Minh City ……………………………………34 Malte STOKHOF Dynamics of Faith: Imam Musa in the Revival of Islamic Teaching in Cambodia ………59 MOHAMAD ZAIN Bin Musa The Re-organization of Islam in Cambodia and Laos………………..70 OMAR FAROUK The Chams and the Malay World …………………………………….86 Kanji NISHIO Notes on the Contributors……………………………………………...94 Workshop Program …………………………………………………....96 CIAS Discussion Paper No.3 © Center for Integrated Area Studies, Kyoto University Yoshida-Honmachi, Sakyo-ku, Kyoto-shi, Kyoto, 606-8501, Japan TEL: +81-75-753-9603 FAX: +81-75-753-9602 E-mail: [email protected] http://www.cias.kyoto-u.ac.jp March, 2008 2 CIAS Discussion Paper No.3 Preface I think it would be no exaggeration to suggest that Southeast Asian nations are boom- ing, not only because of their rapid economic development but also because of their long experiences of maintaining harmony and tolerance between the diverse ethnic and religious components of their populations. The Southeast Asian Muslims, for example, once re- garded as being peripheral to the world of Islam, are now becoming recognized as model Muslim leaders with exceptional abilities to manage difficult tasks such as their own coun- try‟s economic development, the Islamic financial system, democratization and even aero- nautics. -

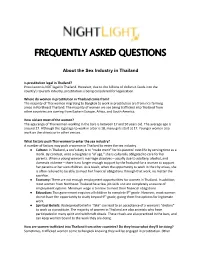

Frequently Asked Questions

FREQUENTLY ASKED QUESTIONS About the Sex Industry in Thailand Is prostitution legal in Thailand? Prostitution is NOT legal in Thailand. However, due to the billions of dollars it feeds into the country’s tourism industry, prostitution is being considered for legalization. Where do women in prostitution in Thailand come from? The majority of Thai women migrating to Bangkok to work in prostitution are from rice farming areas in Northeast Thailand. The majority of women we see being trafficked into Thailand from other countries are coming from Eastern Europe, Africa, and South America. How old are most of the women? The age range of Thai women working in the bars is between 17 and 50 years old. The average age is around 27. Although the legal age to work in a bar is 18, many girls start at 17. Younger women also work on the streets or in other venues. What factors push Thai women to enter the sex industry? A number of factors may push a woman in Thailand to enter the sex industry. ● Culture: In Thailand, a son’s duty is to “make merit” for his parents’ next life by serving time as a monk. By contrast, once a daughter is “of age,” she is culturally obligated to care for her parents. When a young woman’s marriage dissolves—usually due to adultery, alcohol, and domestic violence—there is no longer enough support by the husband for a woman to support her parents or her own children. As a result, when the opportunity to work in the city arises, she is often relieved to be able to meet her financial obligations through that work, no matter the sacrifice. -

Migrant Smuggling in Asia

Migrant Smuggling in Asia An Annotated Bibliography August 2012 2 Knowledge Product: !"#$%&'()!*##+"&#("&(%)"% An Annotated Bibliography Printed: Bangkok, August 2012 Authorship: United Nations O!ce on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) Copyright © 2012, UNODC e-ISBN: 978-974-680-330-4 "is publication may be reproduced in whole or in part and in any form for educational or non-pro#t purposes without special permission from the copyright holder, provided acknowledgement of the source is made. UNODC would appreciate receiving a copy of any publication that uses this publication as a source. No use of this publication may be made for resale or any other commercial purpose whatsoever without prior permission in writing from the United Nations O!ce on Drugs and Crime. Applications for such permission, with a statement of purpose and intent of the reproduction, should be addressed to UNODC, Regional Centre for East Asia and the Paci#c. Cover photo: Courtesy of OCRIEST Product Feedback: Comments on the report are welcome and can be sent to: Coordination and Analysis Unit (CAU) Regional Centre for East Asia and the Paci#c United Nations Building, 3 rd Floor Rajdamnern Nok Avenue Bangkok 10200, "ailand Fax: +66 2 281 2129 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.unodc.org/eastasiaandpaci#c/ UNODC gratefully acknowledges the #nancial contribution of the Government of Australia that enabled the research for and the production of this publication. Disclaimers: "is report has not been formally edited. "e contents of this publication do not necessarily re$ect the views or policies of UNODC and neither do they imply any endorsement. -

Emancipating Modern Slaves: the Challenges of Combating the Sex

Union College Union | Digital Works Honors Theses Student Work 6-2013 Emancipating Modern Slaves: The hC allenges of Combating the Sex Trade Rachel Mann Union College - Schenectady, NY Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalworks.union.edu/theses Part of the Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons, Inequality and Stratification Commons, and the Political Science Commons Recommended Citation Mann, Rachel, "Emancipating Modern Slaves: The hC allenges of Combating the Sex Trade" (2013). Honors Theses. 700. https://digitalworks.union.edu/theses/700 This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Work at Union | Digital Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of Union | Digital Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. EMANCIPATING MODERN SLAVES: THE CHALLENGES OF COMBATING THE SEX TRADE By Rachel J. Mann * * * * * * * * * Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Honors in the Department of Political Science UNION COLLEGE June, 2013 ABSTRACT MANN, RACHEL Emancipating Modern Slaves: The Challenges of Combating the Sex Trade, June 2013 ADVISOR: Thomas Lobe The trafficking and enslavement of women and children for sexual exploitation affects millions of victims in every region of the world. Sex trafficking operates as a business, where women are treated as commodities within a global market for sex. Traffickers profit from a supply of vulnerable women, international demand for sex slavery, and a viable means of transporting victims. Globalization and the expansion of free market capitalism have increased these factors, leading to a dramatic increase in sex trafficking. Globalization has also brought new dimensions to the fight against sex trafficking. -

Combating Trafficking of Women and Children in South Asia

CONTENTS COMBATING TRAFFICKING OF WOMEN AND CHILDREN IN SOUTH ASIA Regional Synthesis Paper for Bangladesh, India, and Nepal APRIL 2003 This book was prepared by staff and consultants of the Asian Development Bank. The analyses and assessments contained herein do not necessarily reflect the views of the Asian Development Bank, or its Board of Directors or the governments they represent. The Asian Development Bank does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this book and accepts no responsibility for any consequences of their use. i CONTENTS CONTENTS Page ABBREVIATIONS vii FOREWORD xi EXECUTIVE SUMMARY xiii 1 INTRODUCTION 1 2 UNDERSTANDING TRAFFICKING 7 2.1 Introduction 7 2.2 Defining Trafficking: The Debates 9 2.3 Nature and Extent of Trafficking of Women and Children in South Asia 18 2.4 Data Collection and Analysis 20 2.5 Conclusions 36 3 DYNAMICS OF TRAFFICKING OF WOMEN AND CHILDREN IN SOUTH ASIA 39 3.1 Introduction 39 3.2 Links between Trafficking and Migration 40 3.3 Supply 43 3.4 Migration 63 3.5 Demand 67 3.6 Impacts of Trafficking 70 4 LEGAL FRAMEWORKS 73 4.1 Conceptual and Legal Frameworks 73 4.2 Crosscutting Issues 74 4.3 International Commitments 77 4.4 Regional and Subregional Initiatives 81 4.5 Bangladesh 86 4.6 India 97 4.7 Nepal 108 iii COMBATING TRAFFICKING OF WOMEN AND CHILDREN 5APPROACHES TO ADDRESSING TRAFFICKING 119 5.1 Stakeholders 119 5.2 Key Government Stakeholders 120 5.3 NGO Stakeholders and Networks of NGOs 128 5.4 Other Stakeholders 129 5.5 Antitrafficking Programs 132 5.6 Overall Findings 168 5.7 -

Ethnicity and Forest Resource Use and Management

Page 1 of 11 ETHNICITY AND FOREST RESOURCE USE AND MANAGEMENT IN CAMBODIA BACKGROUND The Community Forestry Working Group established a typological framework to examine the inter-related issues of ecology, tenure, and ethnicity in relation to forest resource perspectives, use and management by rural communities in Cambodia. The typology will serve as a base of knowledge and documentation and as a conceptual framework for understanding community resource use. This will be useful for defining appropriate objectives, strategies, and methodologies to support community forestry development interventions. Specifically, understanding and describing the three underlying typological topics (tenure, ethnicity, ecology) will be helpful for: Establishing a framework for better identification and understanding of existing community forestry activities in Cambodia; A possible identification of appropriate places or regions where community forestry would be relevant and useful for sustainable forest management and for improvement of people's livelihoods; A useful instrument to design programs in a given region with community involvement. INTRODUCTION The population of Cambodia was estimated to be 11,437,656 in 1998. This population consists of different ethnic groups, including Khmer, Cham, Vietnamese, Chinese and hill tribes. Ethnic groups in Cambodian society possess a number of economic and demographic commonalties. For example, minority ethnic villages are more common among the poorest than among the richest quintile of villages (5.3 percent versus 3.2 percent) ( Ministry of Planning, 1999) . While commonalties exist, ethnic groups in Cambodia also preserve differences in their social and cultural institutions. The major differences among the various ethnic groups lie in historical, social organization, language, custom, habitant, belief and religion. -

Register in Eastern Cham: Phonological, Phonetic and Sociolinguistic Approaches

REGISTER IN EASTERN CHAM: PHONOLOGICAL, PHONETIC AND SOCIOLINGUISTIC APPROACHES A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Marc Brunelle August 2005 © 2005 Marc Brunelle REGISTER IN EASTERN CHAM: PHONOLOGICAL, PHONETIC AND SOCIOLINGUISTIC APPROACHES Marc Brunelle, Ph.D. Cornell University, 2005 The Chamic language family is often cited as a test case for contact linguistics. Although Chamic languages are Austronesian, they are claimed to have converged with Mon-Khmer languages and adopted features from their closest neighbors. A good example of such a convergence is the realization of phonological register in Cham dialects. In many Southeast Asian languages, the loss of the voicing contrast in onsets has led to the development of two registers, bundles of features that initially included pitch, voice quality, vowel quality and durational differences and that are typically realized on rimes. While Cambodian Cham realizes register mainly through vowel quality, just like Khmer, the registers of the Cham dialect spoken in south- central Vietnam (Eastern Cham) are claimed to have evolved into tone, a property that plays a central role in Vietnamese phonology. This dissertation evaluates the hypothesis that contact with Vietnamese is responsible for the recent evolution of Eastern Cham register by exploring the nature of the sound system of Eastern Cham from phonetic, phonological and sociolinguistic perspectives. Proponents of the view that Eastern Cham has a complex tone system claim that tones arose from the phonemicization of register allophones conditioned by codas after the weakening or deletion of coda stops and laryngeals. -

Modernity for Young Rural Migrant Women Working in Garment Factories in Vientiane

MODERNITY FOR YOUNG RURAL MIGRANT WOMEN WORKING IN GARMENT FACTORIES IN VIENTIANE ຄວາມເປັນສະໄໝໃໝສ່ າ ລບັ ຍງິ ສາວທ່ ເປັນແຮງງານຄ່ ອ ນ ຍາ້ ຍ ເຮັດວຽກໃນໂຮງງານ-ຕດັ ຫຍບິ ຢນ່ ະຄອນຫຼວງ ວຽງຈນັ Ms Rakounna SISALEUMSAK MASTER DEGREE NATIONAL UNIVERISTY OF LAOS 2012 MODERNITY FOR YOUNG RURAL MIGRANT WOMEN WORKING IN GARMENT FACTORIES IN VIENTIANE ຄວາມເປັນສະໄໝໃໝສ່ າ ລບັ ຍງິ ສາວທ່ ເປັນແຮງງານເຄ່ ອ ນ ຍາ້ ຍເຮັດວຽກໃນໂຮງງານ-ຕດັ ຫຍບິ ຢນ່ ະຄອນຫຼວງວຽງຈນັ A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE OFFICE IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE MASTER DEGREE IN INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT STUDIES Rakounna SISALEUMSAK National University of Laos Advisor: Dr. Kabmanivanh PHOUXAY Chiang Mai University Advisor: Assistant Professor Dr. Pinkaew LAUNGARAMSRI © Copyright by National University of Laos 2012 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This thesis would not have been accomplished without valuable help and inputs from numerous people. First of all I would like to express my sincere appreciation to my supervisors Dr. Kabmanivanh Phouxay and Assistant Professor Dr. Pinkaew Laungaramsri for their valuable support, critical comments and advice which has helped shaped my thesis. In addition I would also like to express my sincere gratitude to Dr. Chayan Vaddhanaphuti, for the constant guidance and advice provided which has helped to deepen my understanding of the various concepts and development issues. I also wish to thank all the lecturers, professors and staff, from NUOL and CMU, for helping to increase my knowledge and widen my perspectives on development issues in Laos and in the region. My special thanks to Dr Seksin Srivattananukulkit for advising me to take this course and also to Dr Chaiwat Roongruangsee for his constant encouragement and words of wisdom which has helped motivate me to continue to write this thesis. -

Sex-Trafficking in Cambodia 1

Running head: SEX-TRAFFICKING IN CAMBODIA 1 Sex-Trafficking in Cambodia Assessing the Role of NGOs in Rebuilding Cambodia Katherine Wood A Senior Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation in the Honors Program Liberty University Spring 2014 SEX-TRAFFICKING 2 Acceptance of Senior Honors Thesis This Senior Honors Thesis is accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation from the Honors Program of Liberty University. ______________________________ Steven Samson, Ph.D. Thesis Chair ______________________________ Thomas Metallo, Ph.D. Committee Member ______________________________ Robert F. Ritchie, M.A. Committee Member ______________________________ Brenda Ayres, Ph.D. Honors Director ______________________________ Date SEX-TRAFFICKING 3 Abstract The anti-slavery and other freedom fighting movements of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries did not abolish all forms of slavery. Many forms of modern slavery thrive in countries all across the globe. The sex trafficking trade has intensified despite the advocacy of many human rights-based groups. Southeast Asia ranks very high in terms of the source, transit, and destination of sex trafficking. In particular, human trafficking of women and girls for the purpose of forced prostitution remains an increasing problem in Cambodia. Cambodia’s cultural traditions and the breakdown of law under the Khmer Rouge and Democratic Kampuchea have contributed to the current governing policies which maintain democracy only at the surface level of administration. -

Combating Child Sex Tourism in a New Tourism Destination

DECLARATION Name of candidate: Phouthone Sisavath This thesis entitled: “Combating Child Sex Tourism in a new tourism destination” is submitted in partial fulfilment for the requirement for the Unitec New Zealand degree of Master of Business. CANDIDATE’S DECLARATION I confirm that: This thesis is my own work The contribution of supervision and others to this thesis is consistent with Unitec‟s Regulations and Policies Research for this thesis has been conducted with approval of the Unitec Research Ethics Committee Policy and Procedure, and has fulfilled any requirements set for this thesis by the Unitec Ethics Committee. The Research Ethics Committee Approval Number is: 2011-1211 Candidate Signature:..............................................Date:…….……….………… Student ID number: 1351903 i ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This thesis would not have been completed without the support and assistance of some enthusiastic people. I would like to thank the principal supervisor of the thesis, Prof. Ken Simpson. He has provided the most valuable and professional guidance and feedback, and he gave me the most support and encouragement in the research. I would also like to thank the associate supervisor, Ken Newlands for his valuable comments on the draft of the thesis. I would also like to give a big thank you to all active participants from both the Lao government agencies and international organisations, which have provided such meaningful information during the research. I would also like to acknowledge and give specially thank to my parents. I might not get to where I am today without their support and encouragement throughout my study here in New Zealand. Finally, I wish to thank my lovely partner Vilayvanh for her understanding and patience and for her consistent positive attitude in every condition and situation. -

Prayer Cards | Joshua Project

Pray for the Nations Pray for the Nations Akha in Vietnam Alu in Vietnam Population: 23,000 Population: 3,900 World Popl: 682,000 World Popl: 15,200 Total Countries: 5 Total Countries: 3 People Cluster: Hani People Cluster: Tibeto-Burman, other Main Language: Akha Main Language: Nisu, Eastern Main Religion: Ethnic Religions Main Religion: Ethnic Religions Status: Unreached Status: Unreached Evangelicals: 0.30% Evangelicals: 0.00% Chr Adherents: 5.00% Chr Adherents: 0.19% Scripture: Complete Bible Scripture: New Testament www.joshuaproject.net www.joshuaproject.net Source: Frank Starmer Source: Operation China, Asia Harvest "Declare his glory among the nations." Psalm 96:3 "Declare his glory among the nations." Psalm 96:3 Pray for the Nations Pray for the Nations Arem in Vietnam Bih in Vietnam Population: 100 Population: 500 World Popl: 900 World Popl: 500 Total Countries: 2 Total Countries: 1 People Cluster: Mon-Khmer People Cluster: Cham Main Language: Arem Main Language: Rade Main Religion: Ethnic Religions Main Religion: Buddhism Status: Unreached Status: Unreached Evangelicals: 0.00% Evangelicals: 1.00% Chr Adherents: 0.00% Chr Adherents: 3.00% Scripture: Unspecified Scripture: Complete Bible www.joshuaproject.net www.joshuaproject.net Source: Asia Harvest "Declare his glory among the nations." Psalm 96:3 "Declare his glory among the nations." Psalm 96:3 Pray for the Nations Pray for the Nations Cham, Eastern in Vietnam Cham, Western in Vietnam Population: 133,000 Population: 47,000 World Popl: 133,900 World Popl: 325,600 Total Countries: -

Prostitution Stigma and Its Effect on the Working Conditions, Personal Lives, and Health of Sex Workers

The Journal of Sex Research ISSN: 0022-4499 (Print) 1559-8519 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/hjsr20 Prostitution Stigma and Its Effect on the Working Conditions, Personal Lives, and Health of Sex Workers Cecilia Benoit, S. Mikael Jansson, Michaela Smith & Jackson Flagg To cite this article: Cecilia Benoit, S. Mikael Jansson, Michaela Smith & Jackson Flagg (2017): Prostitution Stigma and Its Effect on the Working Conditions, Personal Lives, and Health of Sex Workers, The Journal of Sex Research, DOI: 10.1080/00224499.2017.1393652 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2017.1393652 Published online: 17 Nov 2017. Submit your article to this journal View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=hjsr20 Download by: [University of Victoria] Date: 17 November 2017, At: 13:09 THE JOURNAL OF SEX RESEARCH,00(00), 1–15, 2017 Copyright © The Society for the Scientific Study of Sexuality ISSN: 0022-4499 print/1559-8519 online DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2017.1393652 ANNUAL REVIEW OF SEX RESEARCH SPECIAL ISSUE Prostitution Stigma and Its Effect on the Working Conditions, Personal Lives, and Health of Sex Workers Cecilia Benoit and S. Mikael Jansson Centre for Addictions Research of British Columbia, University of Victoria; and Centre for Addictions Research of British Columbia, University of Victoria Michaela Smith Centre for Addictions Research of British Columbia, University of Victoria; Jackson Flagg Centre for Addictions Research of British Columbia, University of Victoria Researchers have shown that stigma is a fundamental determinant of behavior, well-being, and health for many marginalized groups, but sex workers are notably absent from their analyses.