Principles of Electronic Media, 2/E

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tuning Into the On-Demand Streaming Culture—Hollywood Guilds’ Evolution Imperative in Today’S Media Landscape

UCLA UCLA Entertainment Law Review Title Tuning Into the On-Demand Streaming Culture—Hollywood Guilds’ Evolution Imperative in Today’s Media Landscape Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/2152q2t4 Journal UCLA Entertainment Law Review, 27(1) ISSN 1073-2896 Author Roth, Blaine Publication Date 2020 DOI 10.5070/LR8271048856 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California TUNING INTO THE ON-DEMAND STREAMING CULTURE— Hollywood Guilds’ Evolution Imperative in Today’s Media Landscape Blaine Roth Abstract Hollywood television and film production has largely been unionized since the early 1930s. Today, due in part to technological advances, the industry is much more expansive than it has ever been, yet the Hollywood unions, known as “guilds,” have arguably not evolved at a similar pace. Although the guilds have adapted to the needs of their members in many aspects, have they suc- cessfully adapted to the evolving Hollywood business model? This Comment puts a focus on the Writers Guild of America, Directors Guild of America, and the Screen Actors Guild, known as SAG-AFTRA following its merger in 2012, and asks whether their respective collective bargaining agreements are out-of- step with the evolution of the industry over the past ten years, particularly in the areas of new media and the direct-to-consumer model. While analyzing the guilds in the context of the industry environment as it is today, this Com- ment contends that as the guilds continue to feel more pronounced effects from the evolving media landscape, they will need to adapt at a much more rapid pace than ever before in order to meet the needs of their members. -

Finding Aid to the Historymakers ® Video Oral History with Douglas Holloway

Finding Aid to The HistoryMakers ® Video Oral History with Douglas Holloway Overview of the Collection Repository: The HistoryMakers®1900 S. Michigan Avenue Chicago, Illinois 60616 [email protected] www.thehistorymakers.com Creator: Holloway, Douglas V., 1954- Title: The HistoryMakers® Video Oral History Interview with Douglas Holloway, Dates: December 13, 2013 Bulk Dates: 2013 Physical 9 uncompressed MOV digital video files (4:10:46). Description: Abstract: Television executive Douglas Holloway (1954 - ) is the president of Ion Media Networks, Inc. and was an early pioneer of cable television. Holloway was interviewed by The HistoryMakers® on December 13, 2013, in New York, New York. This collection is comprised of the original video footage of the interview. Identification: A2013_322 Language: The interview and records are in English. Biographical Note by The HistoryMakers® Television executive Douglas V. Holloway was born in 1954 in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. He grew up in the inner-city Pittsburgh neighborhood of Homewood. In 1964, Holloway was part of the early busing of black youth into white neighborhoods to integrate Pittsburgh schools. In 1972, he entered Northeastern University in Boston, Massachusetts as a journalism major. Then, in 1974, Holloway transferred to Emerson College, and graduated from there in 1975 with his B.S. degree in mass communications and television production. In 1978, he received his M.B.A. from Columbia University with an emphasis in marketing and finance. Holloway was first hired in a marketing position with General Foods (later Kraft Foods). He soon moved into the television and communications world, and joined the financial strategic planning team at CBS in 1980. -

Media Ownership Chart

In 1983, 50 corporations controlled the vast majority of all news media in the U.S. At the time, Ben Bagdikian was called "alarmist" for pointing this out in his book, The Media Monopoly . In his 4th edition, published in 1992, he wrote "in the U.S., fewer than two dozen of these extraordinary creatures own and operate 90% of the mass media" -- controlling almost all of America's newspapers, magazines, TV and radio stations, books, records, movies, videos, wire services and photo agencies. He predicted then that eventually this number would fall to about half a dozen companies. This was greeted with skepticism at the time. When the 6th edition of The Media Monopoly was published in 2000, the number had fallen to six. Since then, there have been more mergers and the scope has expanded to include new media like the Internet market. More than 1 in 4 Internet users in the U.S. now log in with AOL Time-Warner, the world's largest media corporation. In 2004, Bagdikian's revised and expanded book, The New Media Monopoly , shows that only 5 huge corporations -- Time Warner, Disney, Murdoch's News Corporation, Bertelsmann of Germany, and Viacom (formerly CBS) -- now control most of the media industry in the U.S. General Electric's NBC is a close sixth. Who Controls the Media? Parent General Electric Time Warner The Walt Viacom News Company Disney Co. Corporation $100.5 billion $26.8 billion $18.9 billion 1998 revenues 1998 revenues $23 billion 1998 revenues $13 billion 1998 revenues 1998 revenues Background GE/NBC's ranks No. -

Design, Construction and Testing of a Low Energy Digital Frequency Modulation (FM) Transmitter

International Journal of Scientific & Engineering Research Volume 11, Issue 1, January-2020 534 ISSN 2229-5518 Design, Construction and Testing of a Low Energy Digital Frequency Modulation (FM) Transmitter JP. C. Mbagwu, F.M.Ezike, J.O.Ozuomba Abstract---- A rapidly growing demand for the use of Frequency Modulation (FM) transmitter exists within institutions and individuals. The FM transmitters are however a complex equipment demanding high power supply, high voltage system design, critical maintenance and exorbitant price. These problems of the transmitter constitute major impediments to institutions and individuals that may wish to adopt radio broadcast as means of electronic media. This study was therefore carried out to design and construct an FM transmitter that is of low cost, and simple in maintenance, efficient in use and yet operating on low power supply. The FM transmitter is designed to be received at a range of about 100metres in free air. The transmitter has a capacitor microphone which picks up very weak sound signals, a transistor, resistors, inductor, and capacitors. The design procedure involves the modification of an output of the transmitter. Based on the procedures adopted and the tests carried out, the specific findings include a range of 102.2MHz of transmission from a 9V DC battery. The work indicated that the practical frequency modulated (FM) transmitter requiring a low power can be designed and constructed. Index Terms----Frequency Modulation, FM Transmitter, Radio Broadcast, Antenna. 1.0 INTRODUCTION combined in one unit are called a transceiver. The In electronics and telecommunication, a transmitter term transmitter is often abbreviated ‘‘XMTR’’ or or radio transmitter is an electronic device which ‘‘TX’’ in technical documents. -

News Release

NEWS RELEASE FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Media contacts: June 4, 2012 Heather Wilner Verizon 908-559-6407 [email protected] Cathy Clarke CNC Associates for Olympusat 508-833-8533 [email protected] Verizon FiOS TV Becomes the Nation’s Leading Provider of Spanish-Language Programming FiOS TV Gives Customers The Most HD Spanish-language Channels Available Nationwide, With 10 New Channels from Olympusat and Multimedios Television NEW YORK – Verizon FiOS TV has become the country’s leading television provider of Spanish-language channels, announcing today the launch of 10 new Spanish-language channels in high definition. Verizon now offers up to 75 Spanish-language channels on FiOS TV, dependent on the local channels available in each market. Nine of the 10 new Spanish-language HD channels are provided by Olympusat Inc., a leading independent distributor of Hispanic content in the United States. Known as ULTRA Verizon News Release, page 2 HDPlex, the Olympusat channels are: Ultra Cine, Ultra Fiesta, Ultra Kidz, Ultra Mex, Ultra Luna, Ultra Macho, Ultra Film, Ultra Docu and Ultra Clásico. The 10th channel, Multimedios Television, offers Spanish-language family and entertainment programming broadcast from Monterrey, Mexico. FiOS TV recently completed the launch of all 10 channels. In addition, Verizon announced last week a new multi-year carriage agreement with Univision Communications, Inc., which includes the launch of three new networks – Univision Deportes, Univision tlnovelas and FOROtv – as well as rights for multiplatform and on demand viewing. “Our customers have told us that high-quality Spanish-language programming helps to keep their culture alive, and we’re helping to make that happen by giving them the content that they want,” said Michelle Webb, director of content strategy and acquisition for Verizon. -

Electrical Engineering (ELEC ENG) 1

Electrical Engineering (ELEC_ENG) 1 Prerequisite: ELEC_ENG 302-0 or equivalent. ELECTRICAL ENGINEERING ELEC_ENG 334-0 Fundamentals of Blockchains and Decentralization (1 Unit) (ELEC_ENG) This course is partly an introduction to the fundamentals of blockchains and decentralized applications and partly a springboard toward ELEC_ENG 302-0 Probabilistic Systems (1 Unit) deeper understanding and further exploration. The course explains Introduction to probability theory and its applications. Axioms of how blockchains work; teaches the underlying fundamentals of probability, distributions, discrete and continuous random variables, distributed consensus; provides hands-on experience through computer conditional and joint distributions, correlation, limit laws, connection assignments; and also touches upon economic and policy issues. to statistics, and applications in engineering systems. May not receive Prerequisites: COMP_SCI 212-0 or ELEC_ENG 302-0 or equivalent or credit for both ELEC_ENG 302-0 and any of the following: IEMS 202-0; graduate standing and basic programming skills. MATH 310-1; STAT 320-1; ELEC_ENG 383-0, ELEC_ENG 385-0. Corequisite: MATH 228-2 or equivalent. ELEC_ENG 353-0 Digital Microelectronics (1 Unit) Logic families, comparators, A/D and D/A converters, combinational ELEC_ENG 307-0 Communications Systems (1 Unit) systems, sequential systems, solid-state memory, largescale integrated Analysis of analog and digital communications systems, including circuits, and design of electronic systems. modulation, transmission, and demodulation of AM, FM, and TV systems. Prerequisites: COMP_ENG 203-0, ELEC_ENG 225-0. Design issues, channel distortion and loss, bandwidth limitations, additive noise. ELEC_ENG 359-0 Digital Signal Processing (1 Unit) Prerequisites: ELEC_ENG 222-0, ELEC_ENG 302-0 or equivalent. Discrete-time signals and systems. -

Esf-15 Public Information & Warning

ESF-15 PUBLIC INFORMATION & WARNING CONTENTS PAGE I. PURPOSE ESF 15.2 II. SITUATIONS AND ASSUMPTIONS ESF 15.2 A. Situations ESF 15.2 B. Assumptions ESF 15.3 III. WARNING SYSTEMS ESF 15.3 A. General ESF 15.3 B. Primary Warning System ESF 15.4 C. Alternate (redundant) Warning System ESF 15.7 D. Additional Tools for Warning ESF 15.10 E. Vulnerable Populations ESF 15.10 IV. PUBLIC INFORMATION SYSTEM ESF 15.10 A. General ESF 15.10 B. Joint Information System (JIS) ESF 15.11 C. Public Information Coordination Center (PICC) ESF 15.11 D. Interpreters / Functional Needs / Vulnerable Populations ESF 15.12 V. CONCEPT OF OPERATIONS ESF 15.12 A. Operational Time Frames ESF 15.12 VI. ORGANIZATION AND ASSIGNMENT RESPONSIBILITIES ESF 15.14 A. Primary Agencies ESF 15.14 B. Support Agencies ESF 15.15 C. State Support Agency ESF 15.15 D. Federal Support Agency ESF 15.15 VII. DIRECTION AND CONTROL ESF 15.15 VIII. CONTINUITY OF OPERATIONS ESF 15.15 A. General ESF 15.15 B. Alternate site for EOC ESF 15.16 IX. ADMINISTRATION AND LOGISTICS ESF 15.16 X. ESF DEVELOPMENT AND MAINTENANCE ESF 15.16 XI. REFERENCES ESF 15.16 APPENDICES 1. Activation List ESF 15.18 2. Organizational Chart ESF 15.19 3. Media Points of Contact ESF 15.20 4. Format and Procedures for News Releases ESF 15.24 5. Initial Media Advisory on Emergency ESF 15.25 6. Community Bulletin Board Contacts ESF 15.26 7. Interpreters Contact List ESF 15.27 8. Public Information Call Center (PICC) Plan ESF 15.28 9. -

C O L L Ec T Io N Pr O Fil E

Collection Profile Robert Abel & Associates Co-founder of the multiple Clio-winning production firm, Robert Abel & Associates (RA&A), commercial director and producer Robert Abel (1937-2001) is noted as a COLLECTION central figure in the development of computer-generated visual effects. During their most prolific period, RA&A's unique design aesthetic and innovative graphics were seemingly ubiquitous across the electronic media landscape, featured in highly stylized television advertisements (7UP’s “Bubbles” campaign) and the feature films The Andromeda Strain (1971) and Star Trek: The Motion Picture (1979). A native of Cleveland, Ohio, Abel began his UCLA studies in 1958, obtaining dual bachelor degrees in the Department of Theater’s film division and School of Design. Upon graduation, Abel worked under the tutelage of designer John Whitney, who pioneered the use of computer animation with the short film Catalog (1961) and the title sequence for Vertigo (1958) (in collaboration with Saul Bass). Abel would leave Whitney’s employ in the mid-1960s to direct and produce documentary projects that included Sophia: A Self Portrait (1968), Making of the President (1969) and Elvis on Tour (1972). In 1971 Abel formed a partnership with visual effects artist Con Pederson to launch the Hollywood-based production company Robert Abel & Associates, whose primary focus was the creative utilization of computer-aided photographic effects in television commercials and on-air television promotion. As the decade came to a close, RA&A would garner honors from the International Broadcasting Awards and Broadcast Promotion Association for their work with CBS (“Campaign ‘76”), Kawasaki (“The Ultimate Trip”) and a series of iconic Levis Strauss Co. -

The Influence of the Mass Media in the Behavior Students: a Literature Study

International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences 2017, Vol. 7, No. 8 ISSN: 2222-6990 The Influence of the Mass Media in the Behavior Students: A Literature Study Noradilah Abdul Wahab1, Mohd Shahril Othman2, Najmi Muhammad3 1 Universiti Sultan Zainal Abidin (UniSZA), Kampus Gong Badak. Kuala Terengganu 2 Lecturer, Faculty of Islamic Contemporary Studies, Universiti Sultan Zainal Abidin (UniSZA) 3 Universiti Malaysia Perlis (UniMAP), Arau, Perlis. DOI: 10.6007/IJARBSS/v7-i8/3218 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.6007/IJARBSS/v7-i8/3218 Abstract The highly developed and complex of technology has grown up along the current style of the world which had introduces the human to a wide range of communication tools, as well as communications today. Mass media is a means of conveying information simultaneously and accessible to the community all over the world. In present era of globalization, the modernization make it easier for people to carry out their daily lives. However, this sophistication has both positive and negative to the user. The mistake in using this facility will become a threat that can contribute the social problems in society. The objective of this writing is to see the influence of mass media in the formation of student personality. The method of writing is qualitative based on previous studies and research through documents, journals and books related to the discussion of the influence of mass media. The method of literature is the primary basis in this writing that inductively and deductively analyzes by studying literature from both local and western researchers until a strong conclusion in identifying mass media influences on student behavior can be achieved. -

Rtv 3001 Introduction to Telecommunication Section 4324

RTV 3001 INTRODUCTION TO TELECOMMUNICATION SECTION 4324 IMPORTANT INFORMATION: Instructor: William A. Renkus, Ph. D. Lecture: Tuesday, Period 10 (5:10 pm – 6:00 pm) & Thursday, Periods 10 - 11 (5:10 pm 7:05 pm)) Room: TUR L007 Office: 3065 Weimer (subject to change) Office Hours: Wednesday & Friday 1:45 PM – 2:45 PM & by appointment E-mail: [email protected] E-Learning: http://lss.at.ufl.edu/ COURSE DESCRIPTION: Electronic media encompass all contemporary paths of mass communication into our lives: radio, television, cable, satellite and the Internet. This course investigates their dynamic influence by unveiling principles that govern media channels of information and entertainment. The goal for students is to understand how our media tools were created, were nurtured into an information industry, and now shape our lives in political, economic, and social ways. We will critically analyze the latest developments from the standpoints of media owners, advertisers, managers, producers, and audiences. COURSE OBJECTIVES: Students will gain knowledge of the telecommunication industry with an emphasis on learning specifically about broadcasting and cable. In addition, changes in new media, business practices, converging markets, and regulatory philosophies will be addressed. This course is designed to offer you an overview of the origins, organizations, and movements that have shaped electronic media. We will learn and discuss the following developments: The historical development of electronic media The technologies involved in the creation of electronic media The structure, economics, and regulation of electronic media The political and legal issues involved in content and management decisions The economics of electronic media, including programming and ratings The lexicon involved within subsets of the telecommunication industry REQUIRED TEXTBOOK: Joseph R. -

Broad&Elec Media.Vp

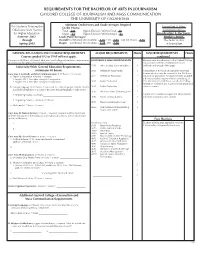

REQUIREMENTS FOR THE BACHELOR OF ARTS IN JOURNALISM GAYLORD COLLEGE OF JOURNALISM AND MASS COMMUNICATION THE UNIVERSITY OF OKLAHOMA Minimum Credit Hours and Grade Averages Required For Students Entering the Credit Hours: Journalism & Mass Oklahoma State System Total - 130 Upper-Division Within Total - 48 Communication— for Higher Education: Major - 33 Upper-Division Within Major -27 Broadcasting & Electronic Summer 2002 Grade Point Averages: Media— 0603G through Overall: Combined OU/Transfer - 2.25 OU - 2.00 Last 60 Hours - 2.25 Bachelor of Arts Spring 2003 Major: Combined OU/Transfer - 2.25 OU - 2.00 in Journalism GENERAL EDUCATION AND COLLEGE REQUIREMENTS MAJOR REQUIREMENTS Hours MAJOR REQUIREMENTS - Hours Courses graded S/U or P/NP will not apply. continued Courses for fulfillment of General Education and College of Journalism requirements JOURNALISM & MASS COMMUNICATION Requirements for admission to the Gaylord College must be from the approved General Education course list. of Journalism and Mass Communication are University-Wide General Education Requirements 1013 Intro. to Mass Communication 3 outlined on the back of this page. (minimum 40 hours) 2033 Writing for Mass Media 3 A maximum of 40 hours of Journalism and Mass Core Area I: Symbolic and Oral Communication (9-19 hours, 3-5 courses) Communication may be counted in the 130 hours a: English Composition (6 hours, 2 courses) 3622 Writing for Broadcast 2 required for graduation. No student will be awarded 1. English 1113, Principles of English Composition a BA in Journalism degree without completing at 2. English 1213, Principles of English Composition 3632 Audio Production 2 least 90 semester credit hours outside the College. -

ATTACHMENT a the FCC’S Newspaper-Broadcast Cross-Ownership Rule: an Analysis

ATTACHMENT A The FCC’s Newspaper-Broadcast Cross-Ownership Rule: An Analysis by Douglas Gomery Douglas Gomery is professor of media economics and history in the College of Journalism at the University of Maryland. His most recent book, Who Owns the Media? (with Ben Compaine), won the 2000 Picard Prize for the best media economics book of the year. He has published 10 other books, some 500 articles in scholarly journals and encyclopedias, written a column, “The Economics of Television,” for the American Journalism Review, and consulted for both the Federal Communications Commission and the Government Accounting Office. Acknowledgments. The author wishes to thank Eileen Appelbaum for her skills in fashioning this study, and Marilyn Moon for her help in crafting its arguments and for her inspiration as one of America's best public policy analysts. ECONOMIC POLICY INSTITUTE 1 Introduction In 1975 the Federal Communications Commission initiated the newspaper-broadcast cross- ownership rule, which bars a single company from owning a newspaper and a broadcast station in the same market. The purpose of the rule is to prevent any single corporate entity from becoming too powerful a single voice within a community, and thus the rule seeks to maximize diversity under the conditions dictated by the marketplace. The cross-ownership ban does not prevent a newspaper from owning a broadcast station in another market, and indeed many large newspapers — such as the New York Times and the Washington Post — own and operate broadcast stations outside their flagship cities (Compaine and Gomery 2000). Media organizations have largely opposed the rule since its inception, and their prospects for eliminating or limiting it brightened in 1996, when the new Telecommunications Act directed the FCC to continually review all ownership rules.