Game On: an Analysis of the Video Game Console Industry

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A History of Video Game Consoles Introduction the First Generation

A History of Video Game Consoles By Terry Amick – Gerald Long – James Schell – Gregory Shehan Introduction Today video games are a multibillion dollar industry. They are in practically all American households. They are a major driving force in electronic innovation and development. Though, you would hardly guess this from their modest beginning. The first video games were played on mainframe computers in the 1950s through the 1960s (Winter, n.d.). Arcade games would be the first glimpse for the general public of video games. Magnavox would produce the first home video game console featuring the popular arcade game Pong for the 1972 Christmas Season, released as Tele-Games Pong (Ellis, n.d.). The First Generation Magnavox Odyssey Rushed into production the original game did not even have a microprocessor. Games were selected by using toggle switches. At first sales were poor because people mistakenly believed you needed a Magnavox TV to play the game (GameSpy, n.d., para. 11). By 1975 annual sales had reached 300,000 units (Gamester81, 2012). Other manufacturers copied Pong and began producing their own game consoles, which promptly got them sued for copyright infringement (Barton, & Loguidice, n.d.). The Second Generation Atari 2600 Atari released the 2600 in 1977. Although not the first, the Atari 2600 popularized the use of a microprocessor and game cartridges in video game consoles. The original device had an 8-bit 1.19MHz 6507 microprocessor (“The Atari”, n.d.), two joy sticks, a paddle controller, and two game cartridges. Combat and Pac Man were included with the console. In 2007 the Atari 2600 was inducted into the National Toy Hall of Fame (“National Toy”, n.d.). -

1. Introduction

Latest Gaming Console 1 1. INTRODUCTION Gaming consoles are one of the best digital entertainment media now available. Gaming consoles were designed for the sole purpose of playing electronic games. A gaming console is a highly specialised piece of hardware that has rapidly evolved since its inception incorporating all the latest advancements in processor technology, memory, graphics, and sound among others to give the gamer the ultimate gaming experience. A console is a command line interface where the personal computer game's settings and variables can be edited while the game is running. But a Gaming Console is an interactive entertainment computer or electronic device that produces a video display signal which can be used with a display device to display a video game. The term "video game console" is used to distinguish a machine designed for consumers to buy and use solely for playing video games from a personal computer, which has many other functions, or arcade machines, which are designed for businesses that buy and then charge others to play. 1.1. Why are games so popular? The answer to this question is to be found in real life. Essentially, most people spend much of their time playing games of some kind or another like making it through traffic lights before they turn red, attempting to catch the train or bus before it leaves, completing the crossword, or answering the questions correctly on Who Wants To Be A Millionaire before the contestants. Office politics forms a continuous, real-life strategy game which many people play, whether they want to or not, with player- definable goals such as ³increase salary to next level´, ³become the boss´, ³score points off a rival colleague and beat them to that promotion´ or ³get a better job elsewhere´. -

Design, Construction and Testing of a Low Energy Digital Frequency Modulation (FM) Transmitter

International Journal of Scientific & Engineering Research Volume 11, Issue 1, January-2020 534 ISSN 2229-5518 Design, Construction and Testing of a Low Energy Digital Frequency Modulation (FM) Transmitter JP. C. Mbagwu, F.M.Ezike, J.O.Ozuomba Abstract---- A rapidly growing demand for the use of Frequency Modulation (FM) transmitter exists within institutions and individuals. The FM transmitters are however a complex equipment demanding high power supply, high voltage system design, critical maintenance and exorbitant price. These problems of the transmitter constitute major impediments to institutions and individuals that may wish to adopt radio broadcast as means of electronic media. This study was therefore carried out to design and construct an FM transmitter that is of low cost, and simple in maintenance, efficient in use and yet operating on low power supply. The FM transmitter is designed to be received at a range of about 100metres in free air. The transmitter has a capacitor microphone which picks up very weak sound signals, a transistor, resistors, inductor, and capacitors. The design procedure involves the modification of an output of the transmitter. Based on the procedures adopted and the tests carried out, the specific findings include a range of 102.2MHz of transmission from a 9V DC battery. The work indicated that the practical frequency modulated (FM) transmitter requiring a low power can be designed and constructed. Index Terms----Frequency Modulation, FM Transmitter, Radio Broadcast, Antenna. 1.0 INTRODUCTION combined in one unit are called a transceiver. The In electronics and telecommunication, a transmitter term transmitter is often abbreviated ‘‘XMTR’’ or or radio transmitter is an electronic device which ‘‘TX’’ in technical documents. -

Applying a Conceptual Mini Game for Supporting Simple Mathematical Calculation Skills: Students’ Perceptions and Considerations

www.sciedu.ca/wje World Journal of Education Vol . 1, No. 1; April 2011 Applying a Conceptual Mini Game for Supporting Simple Mathematical Calculation Skills: Students’ Perceptions and Considerations Chris T. Panagiotakopoulos Department of Primary Education, University of Patras University Campus 26504, Patras, Greece Tel: +30-2610-997-907 E-mail: [email protected] Received: March 4, 2010 Accepted: March 16, 2010 doi:10.5430/wje.v1n1p3 Abstract Mathematics is an area of study that particularly lacks student enthusiasm. Nevertheless, with the help of educational games, any phobias concerning mathematics can be considerably decreased and mathematics can become more appealing. In this study, an educational game addressing mathematics was designed, developed and evaluated by a sample of 33 students of the fifth grade of a primary school. Each student played the educational game “Playing with Numbers” (PwN), performing additions with integers, additions with decimals and multiplications with integers for a total of one hour, divided into four sessions. Next, the sample was asked to provide feedback regarding specific questions, and the analysis of the results showed that the PwN application is attractive and delivers usage. The attraction of the PwN game probably owes its success to its competitive element, as users are driven to achieve high scores. The PwN application was also found to be easy to use, and this made the challenge of achieving a high score more appealing, as success depended only on the cognitive skills of the user and not on any weaknesses or difficulties raised by the application itself. The findings of this study show that students would benefit from educational games and would be happy to work within an environment that motivated them and indirectly forced them to deal with mathematical operations while playing. -

The Effects of Background Music on Video Game Play Performance, Behavior and Experience in Extraverts and Introverts

THE EFFECTS OF BACKGROUND MUSIC ON VIDEO GAME PLAY PERFORMANCE, BEHAVIOR AND EXPERIENCE IN EXTRAVERTS AND INTROVERTS A Thesis Presented to The Academic Faculty By Laura Levy In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science in Psychology in the School of Psychology Georgia Institute of Technology December 2015 Copyright © Laura Levy 2015 THE EFFECTS OF BACKGROUND MUSIC ON VIDEO GAME PLAY PERFORMANCE, BEHAVIOR, AND EXPERIENCE IN EXTRAVERTS AND INTROVERTS Approved by: Dr. Richard Catrambone Advisor School of Psychology Georgia Institute of Technology Dr. Bruce Walker School of Psychology Georgia Institute of Technology Dr. Maribeth Coleman Institute for People and Technology Georgia Institute of Technology Date Approved: 17 July 2015 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I wish to thank the researchers and students that made Food for Thought possible as the wonderful research tool it is today. Special thanks to Rob Solomon, whose efforts to make the game function specifically for this project made it a success. Additionally, many thanks to Rob Skipworth, whose audio engineering expertise made the soundtrack of this study sound beautifully. I express appreciation to the Interactive Media Technology Center (IMTC) for the support of this research, and to my committee for their guidance in making it possible. Finally, I wish to express gratitude to my family for their constant support and quiet bemusement for my seemingly never-ending tenure in graduate school. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS iii LIST OF TABLES vii LIST OF -

Electrical Engineering (ELEC ENG) 1

Electrical Engineering (ELEC_ENG) 1 Prerequisite: ELEC_ENG 302-0 or equivalent. ELECTRICAL ENGINEERING ELEC_ENG 334-0 Fundamentals of Blockchains and Decentralization (1 Unit) (ELEC_ENG) This course is partly an introduction to the fundamentals of blockchains and decentralized applications and partly a springboard toward ELEC_ENG 302-0 Probabilistic Systems (1 Unit) deeper understanding and further exploration. The course explains Introduction to probability theory and its applications. Axioms of how blockchains work; teaches the underlying fundamentals of probability, distributions, discrete and continuous random variables, distributed consensus; provides hands-on experience through computer conditional and joint distributions, correlation, limit laws, connection assignments; and also touches upon economic and policy issues. to statistics, and applications in engineering systems. May not receive Prerequisites: COMP_SCI 212-0 or ELEC_ENG 302-0 or equivalent or credit for both ELEC_ENG 302-0 and any of the following: IEMS 202-0; graduate standing and basic programming skills. MATH 310-1; STAT 320-1; ELEC_ENG 383-0, ELEC_ENG 385-0. Corequisite: MATH 228-2 or equivalent. ELEC_ENG 353-0 Digital Microelectronics (1 Unit) Logic families, comparators, A/D and D/A converters, combinational ELEC_ENG 307-0 Communications Systems (1 Unit) systems, sequential systems, solid-state memory, largescale integrated Analysis of analog and digital communications systems, including circuits, and design of electronic systems. modulation, transmission, and demodulation of AM, FM, and TV systems. Prerequisites: COMP_ENG 203-0, ELEC_ENG 225-0. Design issues, channel distortion and loss, bandwidth limitations, additive noise. ELEC_ENG 359-0 Digital Signal Processing (1 Unit) Prerequisites: ELEC_ENG 222-0, ELEC_ENG 302-0 or equivalent. Discrete-time signals and systems. -

The Influence of the Mass Media in the Behavior Students: a Literature Study

International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences 2017, Vol. 7, No. 8 ISSN: 2222-6990 The Influence of the Mass Media in the Behavior Students: A Literature Study Noradilah Abdul Wahab1, Mohd Shahril Othman2, Najmi Muhammad3 1 Universiti Sultan Zainal Abidin (UniSZA), Kampus Gong Badak. Kuala Terengganu 2 Lecturer, Faculty of Islamic Contemporary Studies, Universiti Sultan Zainal Abidin (UniSZA) 3 Universiti Malaysia Perlis (UniMAP), Arau, Perlis. DOI: 10.6007/IJARBSS/v7-i8/3218 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.6007/IJARBSS/v7-i8/3218 Abstract The highly developed and complex of technology has grown up along the current style of the world which had introduces the human to a wide range of communication tools, as well as communications today. Mass media is a means of conveying information simultaneously and accessible to the community all over the world. In present era of globalization, the modernization make it easier for people to carry out their daily lives. However, this sophistication has both positive and negative to the user. The mistake in using this facility will become a threat that can contribute the social problems in society. The objective of this writing is to see the influence of mass media in the formation of student personality. The method of writing is qualitative based on previous studies and research through documents, journals and books related to the discussion of the influence of mass media. The method of literature is the primary basis in this writing that inductively and deductively analyzes by studying literature from both local and western researchers until a strong conclusion in identifying mass media influences on student behavior can be achieved. -

Gaming, Gamification and BYOD in Academic and Library Settings: Bibliographic Overview Plamen Miltenoff St

St. Cloud State University theRepository at St. Cloud State Library Faculty Publications Library Services 6-2015 Gaming, Gamification and BYOD in academic and library settings: bibliographic overview Plamen Miltenoff St. Cloud State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.stcloudstate.edu/lrs_facpubs Part of the Library and Information Science Commons Recommended Citation Miltenoff, Plamen, "Gaming, Gamification and BYOD in academic and library settings: bibliographic overview" (2015). Library Faculty Publications. 46. https://repository.stcloudstate.edu/lrs_facpubs/46 This Bibliographic Essay is brought to you for free and open access by the Library Services at theRepository at St. Cloud State. It has been accepted for inclusion in Library Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of theRepository at St. Cloud State. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Plamen Miltenoff [email protected] Gaming, Gamification and BYOD in academic and library settings: bibliographic overview Keywords: gaming, gamification, game-based learning, GBL, serious games, Bring Your Own Device, BYOD, mobile devices, Millennials, Generation Y, Generation Z, academic libraries, education, assessment, badges, leaderboards Introduction Lev Vygotsky’s “Zone of proximal development” and his Sociocultural Theory opened new opportunities for interpretations of the learning process. Vygotsky’s ideas overlapped Jean Piaget’s and Erik Erickson’s assertions that cooperative learning, added to experimental learning, enhances the learning process. Peer interaction, according to them, is quintessential in accelerating the learning process (Piaget, 1970; Erickson, 1977; Vygotsky, 1978). Robert Gagné, B.F. Skinner, Albert Bandura, and others contributed and constructivism established itself as a valid theory in learning. Further, an excellent chapter of social learning theories is presented by Anderson, & Dron (2014). -

Openbsd Gaming Resource

OPENBSD GAMING RESOURCE A continually updated resource for playing video games on OpenBSD. Mr. Satterly Updated August 7, 2021 P11U17A3B8 III Title: OpenBSD Gaming Resource Author: Mr. Satterly Publisher: Mr. Satterly Date: Updated August 7, 2021 Copyright: Creative Commons Zero 1.0 Universal Email: [email protected] Website: https://MrSatterly.com/ Contents 1 Introduction1 2 Ways to play the games2 2.1 Base system........................ 2 2.2 Ports/Editors........................ 3 2.3 Ports/Emulators...................... 3 Arcade emulation..................... 4 Computer emulation................... 4 Game console emulation................. 4 Operating system emulation .............. 7 2.4 Ports/Games........................ 8 Game engines....................... 8 Interactive fiction..................... 9 2.5 Ports/Math......................... 10 2.6 Ports/Net.......................... 10 2.7 Ports/Shells ........................ 12 2.8 Ports/WWW ........................ 12 3 Notable games 14 3.1 Free games ........................ 14 A-I.............................. 14 J-R.............................. 22 S-Z.............................. 26 3.2 Non-free games...................... 31 4 Getting the games 33 4.1 Games............................ 33 5 Former ways to play games 37 6 What next? 38 Appendices 39 A Clones, models, and variants 39 Index 51 IV 1 Introduction I use this document to help organize my thoughts, files, and links on how to play games on OpenBSD. It helps me to remember what I have gone through while finding new games. The biggest reason to read or at least skim this document is because how can you search for something you do not know exists? I will show you ways to play games, what free and non-free games are available, and give links to help you get started on downloading them. -

Effects of Controller-Based Locomotion on Player

Effects of Controller-based Locomotion on Player Experience in a Virtual Reality Exploration Game Julian Frommel, Sven Sonntag, Michael Weber Institute of Media Informatics, Ulm University James-Franck Ring Ulm, Germany {firstname.lastname}@uni-ulm.de ABSTRACT 1 INTRODUCTION Entertainment and in particular gaming is currently consid- With the recent release of several consumer grade VR HMDs, ered one of the main application scenarios for virtual reality there has been growing interest in the design and development (VR). The majority of current games rely on any form of loco- of VR games. As a result, player experience research has been motion through the virtual environment while some techniques increasingly concerned with interaction in VR gaming. Games can lead to simulator sickness. Game developers are currently in general as well as VR games frequently require that the implementing a wide variety of locomotion techniques to cope player can move from one position to another. While providing with simulator sickness (e.g. teleportation). In this work we such an interaction is easy in non-VR games it can be quite implemented and evaluated four different controller-based challenging for VR games. Although locomotion is possible locomotion methods that are popular in current VR games for roomscale VR systems like the HTC Vive [12] the available (free teleport, fixpoint teleport, touchpad-based, automatic). space is too limited for the requirements of a lot of games. We conducted a user study (n = 24) in which participants Therefore, game developers employ many different approaches explored a virtual zoo with these four different controller-based to provide locomotion for players. -

Rtv 3001 Introduction to Telecommunication Section 4324

RTV 3001 INTRODUCTION TO TELECOMMUNICATION SECTION 4324 IMPORTANT INFORMATION: Instructor: William A. Renkus, Ph. D. Lecture: Tuesday, Period 10 (5:10 pm – 6:00 pm) & Thursday, Periods 10 - 11 (5:10 pm 7:05 pm)) Room: TUR L007 Office: 3065 Weimer (subject to change) Office Hours: Wednesday & Friday 1:45 PM – 2:45 PM & by appointment E-mail: [email protected] E-Learning: http://lss.at.ufl.edu/ COURSE DESCRIPTION: Electronic media encompass all contemporary paths of mass communication into our lives: radio, television, cable, satellite and the Internet. This course investigates their dynamic influence by unveiling principles that govern media channels of information and entertainment. The goal for students is to understand how our media tools were created, were nurtured into an information industry, and now shape our lives in political, economic, and social ways. We will critically analyze the latest developments from the standpoints of media owners, advertisers, managers, producers, and audiences. COURSE OBJECTIVES: Students will gain knowledge of the telecommunication industry with an emphasis on learning specifically about broadcasting and cable. In addition, changes in new media, business practices, converging markets, and regulatory philosophies will be addressed. This course is designed to offer you an overview of the origins, organizations, and movements that have shaped electronic media. We will learn and discuss the following developments: The historical development of electronic media The technologies involved in the creation of electronic media The structure, economics, and regulation of electronic media The political and legal issues involved in content and management decisions The economics of electronic media, including programming and ratings The lexicon involved within subsets of the telecommunication industry REQUIRED TEXTBOOK: Joseph R. -

Broad&Elec Media.Vp

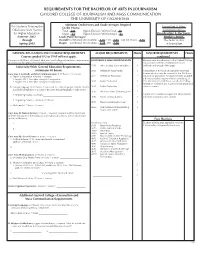

REQUIREMENTS FOR THE BACHELOR OF ARTS IN JOURNALISM GAYLORD COLLEGE OF JOURNALISM AND MASS COMMUNICATION THE UNIVERSITY OF OKLAHOMA Minimum Credit Hours and Grade Averages Required For Students Entering the Credit Hours: Journalism & Mass Oklahoma State System Total - 130 Upper-Division Within Total - 48 Communication— for Higher Education: Major - 33 Upper-Division Within Major -27 Broadcasting & Electronic Summer 2002 Grade Point Averages: Media— 0603G through Overall: Combined OU/Transfer - 2.25 OU - 2.00 Last 60 Hours - 2.25 Bachelor of Arts Spring 2003 Major: Combined OU/Transfer - 2.25 OU - 2.00 in Journalism GENERAL EDUCATION AND COLLEGE REQUIREMENTS MAJOR REQUIREMENTS Hours MAJOR REQUIREMENTS - Hours Courses graded S/U or P/NP will not apply. continued Courses for fulfillment of General Education and College of Journalism requirements JOURNALISM & MASS COMMUNICATION Requirements for admission to the Gaylord College must be from the approved General Education course list. of Journalism and Mass Communication are University-Wide General Education Requirements 1013 Intro. to Mass Communication 3 outlined on the back of this page. (minimum 40 hours) 2033 Writing for Mass Media 3 A maximum of 40 hours of Journalism and Mass Core Area I: Symbolic and Oral Communication (9-19 hours, 3-5 courses) Communication may be counted in the 130 hours a: English Composition (6 hours, 2 courses) 3622 Writing for Broadcast 2 required for graduation. No student will be awarded 1. English 1113, Principles of English Composition a BA in Journalism degree without completing at 2. English 1213, Principles of English Composition 3632 Audio Production 2 least 90 semester credit hours outside the College.