Traditional Opera Consumption As the New Game of Distinction for the Chinese Middle Class

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kūnqǔ in Practice: a Case Study

KŪNQǓ IN PRACTICE: A CASE STUDY A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI‘I AT MĀNOA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN THEATRE OCTOBER 2019 By Ju-Hua Wei Dissertation Committee: Elizabeth A. Wichmann-Walczak, Chairperson Lurana Donnels O’Malley Kirstin A. Pauka Cathryn H. Clayton Shana J. Brown Keywords: kunqu, kunju, opera, performance, text, music, creation, practice, Wei Liangfu © 2019, Ju-Hua Wei ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I wish to express my gratitude to the individuals who helped me in completion of my dissertation and on my journey of exploring the world of theatre and music: Shén Fúqìng 沈福庆 (1933-2013), for being a thoughtful teacher and a father figure. He taught me the spirit of jīngjù and demonstrated the ultimate fine art of jīngjù music and singing. He was an inspiration to all of us who learned from him. And to his spouse, Zhāng Qìnglán 张庆兰, for her motherly love during my jīngjù research in Nánjīng 南京. Sūn Jiàn’ān 孙建安, for being a great mentor to me, bringing me along on all occasions, introducing me to the production team which initiated the project for my dissertation, attending the kūnqǔ performances in which he was involved, meeting his kūnqǔ expert friends, listening to his music lessons, and more; anything which he thought might benefit my understanding of all aspects of kūnqǔ. I am grateful for all his support and his profound knowledge of kūnqǔ music composition. Wichmann-Walczak, Elizabeth, for her years of endeavor producing jīngjù productions in the US. -

Qinqiang Opera Drama Costume Connotation and Aesthetic

2nd International Conference on Education Technology, Management and Humanities Science (ETMHS 2016) Qinqiang opera drama costume connotation and aesthetic implication 1, a Yugang Chen 1Jiangxi Institute of Fashion Technology, Jiangxi, Nanchang, 330201 [email protected] Keywords: Qinqiang opera drama; Clothing; The cultural connotation Abstract. Qinqiang opera drama is one of the most exquisite stylized performance of traditional Chinese local operas. Qinqiang opera drama clothing, and other theatrical performances of traditional clothing similarity is exquisite and stylized, decorative effect as well as the audiences in the symbolization of abstract feelings, dramatic clothes in qinqiang opera drama very expressive aesthetics and art. Introduction Qinqiang opera drama as a traditional Chinese drama conductions, its dramatic clothes also represents the character appearance of traditional drama clothing, under the stylized costumes or wear shows of the respect and inheritance on traditional culture. Studies of qinqiang opera costume for one of the models, style characteristic, found that it contains the cultural connotation and aesthetic implication, the essence of traditional clothing, for the development of qinqiang opera drama has a positive and far-reaching significance. The formation of Qinqiang opera drama clothing Qin has been active in shanxi, gansu and the northwest region is the vast land of an ancient opera. The earliest qinqiang opera originated in shanxi guanzhong area, from the perspective of the change of type c, Qin Sheng, qin three stages. In the qianlong period reached for her best. From the point of geography, shanxi, gansu, ningxia, qinghai, xinjiang northwest five provinces close to geographical culture, so the ancient qin, with its wide sound big voice spoke quickly popular in this area. -

From Story to Script: Towards a Morphology of the Peony Pavilion–– a Dream/ Ghost Drama from Ming China

From Story to Script: towards a Morphology of The Peony Pavilion–– a Dream/ Ghost Drama from Ming China Xiaohuan Zhao University of Otago, Donghua University This article is an attempt to analyze the dramatic structure of the Mudan ting 牡丹 亭 (Peony Pavilion) as a piece of fantasy which Tang Xianzu 湯顯祖 (1550–1616) created through the utilisation of structural devices and techniques of magic tales. The particular model adopted for the textual analysis is that formulated by Vladimir Propp in Morphology of Russian Folktale. This paper starts with a comparison of Russian magic tales Propp investigated for his morphological study and Chinese zhiguai 志怪 tales which provide the prototype for the Mudan ting with a view of justifying the application of the Proppian model. The second part of this paper is devoted to a critical review of the Proppian model and method in terms of function versus non-function, tale versus move, and character versus tale / theatrical role. Further information is also given in this part as a response to challenges and criticisms this article may incur as regards the applicability of the Proppian model in inter-cultural and inter-generic studies. Part Three is a morphological analysis of the dramatic text with a focus on the main storyline revolving around the hero and heroine. In the course of textual analysis, the particular form and sequence of functions is identified, the functional scheme of each move presented, and the distribution of dramatis personae in accordance with the sphere(s) of action of characters delineated. Finally this paper concludes with a presentation of the overall dramatic structure and strategy of this play. -

Western Opera and International Practices in the Beijing National Centre for the Performing Arts

ENCATC JOURNAL OF CULTURAL MANAGEMENT & POLICY || Vol. 7, Issue 1, 2017 || ISSN 2224-2554 “Originated in China”: Western opera and international practices in the Beijing National Centre for the Performing Arts Silvia Giordano Management and Development of Cultural Heritage, IMT Institute for Advanced Studies, Lucca, Italy [email protected] Submission date: 19.03.2017 • Acceptance date: 15.06.2017 • Publication date: 10.12.2017 ABSTRACT The international reputation of Western operas – with artists and producers moving across the world’s opera houses – has become even more global in recent years. Nevertheless, the field of opera has never been analyzed in terms of strategies Keywords: to foster this vocation in line with the development of the emerging markets outside Europe. China is one of the most flourishing among them in terms of the creation of Western opera grand theaters able to perform Western opera together with a strong indigenous op- era tradition. Due to the novelty of such appealing context, a case study analysis would China provide an evidence-based account of the questions raised as to how this ambiva- lence is managed: How does a Chinese opera house performing Western opera find Globalization its legitimacy in the international arena? Which are the artistic and production strate- gies fitting under the definition of international practices? Why is the Chinese context Cultural identity appealing to the Western opera industry? This paper, therefore, aims to address such questions by examining the international practices of the National Centre for Perform- Internationalization ing Arts (NCPA) in Beijing, in view of the process of building a reputation in the global opera network, with a particular focus on the artistic program, casting choices, the attractive power of the theatre and the exchange of expertise between Western and Chinese operatic contexts. -

The Art of Facial Makeup in Chinese Opera

Rochester Institute of Technology RIT Scholar Works Theses 8-28-1997 The Art of facial makeup in Chinese opera Hsueh-Fang Liu Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.rit.edu/theses Recommended Citation Liu, Hsueh-Fang, "The Art of facial makeup in Chinese opera" (1997). Thesis. Rochester Institute of Technology. Accessed from This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by RIT Scholar Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses by an authorized administrator of RIT Scholar Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Rochester Institute of Technology A Thesis Submitted To The Faculty Of The College Of Imaging Arts And Sciences In Candidacy For The Degree Of Master Of Fine Arts Title The Art of Facial Makeup in Chinese Opera By Hsueh-Fang Liu August 28, 1997 Chief Advisor: Nancy Ciolek -'Si(";-NATUR[ Ha~ue Associate Adviser: lim Ver SIC-A1U"-' ------------------------ --OATEfii..--ZZ C;-r6--Q 7 Associate Adviser: Robert Keou~h DATE" --------- --- --_ _- ------- . p~_/!:~_[z Chairperson: Nancy Giolek __ DATE I, Hsueh-Fan~ Liu, hereby grant permission to the Wallace Memorial Library of RIT to reproduce my thesis in whole or in part_ Any reproduction will not be commercial use or profit. II Dedication to: My husband, Wei-Chang Chung who have supported me in my graduate studies, especially in my thesis work. Special thanks to my thesis committee: Nancy Ciolek, )im Ver Hague, & Patrick Byrnes for all of their knowledge and assistance. Robert Keough for being very helpful in many ways.. -

An Ideological Analysis of the Birth of Chinese Indie Music

REPHRASING MAINSTREAM AND ALTERNATIVES: AN IDEOLOGICAL ANALYSIS OF THE BIRTH OF CHINESE INDIE MUSIC Menghan Liu A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS December 2012 Committee: Jeremy Wallach, Advisor Kristen Rudisill Esther Clinton © 2012 MENGHAN LIU All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Jeremy Wallach, Advisor This thesis project focuses on the birth and dissemination of Chinese indie music. Who produces indie? What is the ideology behind it? How can they realize their idealistic goals? Who participates in the indie community? What are the relationships among mainstream popular music, rock music and indie music? In this thesis, I study the production, circulation, and reception of Chinese indie music, with special attention paid to class, aesthetics, and the influence of the internet and globalization. Borrowing Stuart Hall’s theory of encoding/decoding, I propose that Chinese indie music production encodes ideologies into music. Pierre Bourdieu has noted that an individual’s preference, namely, tastes, corresponds to the individual’s profession, his/her highest educational degree, and his/her father’s profession. Whether indie audiences are able to decode the ideology correctly and how they decode it can be analyzed through Bourdieu’s taste and distinction theory, especially because Chinese indie music fans tend to come from a community of very distinctive, 20-to-30-year-old petite-bourgeois city dwellers. Overall, the thesis aims to illustrate how indie exists in between the incompatible poles of mainstream Chinese popular music and Chinese rock music, rephrasing mainstream and alternatives by mixing them in itself. -

Kunqu Opera in the Last Hundred Years in China

Review of Educational Theory | Volume 02 | Issue 04 | October 2019 Review of Educational Theory https://ojs.bilpublishing.com/index.php/ret REVIEW Kunqu Opera in the Last Hundred Years in China Yue Wang* The University of Milan, Milan, 20122, Italy ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Article history Kunqu, literally means kun melody, is one of the most ancient forms of Received: 26 September 2019 Chinese opera. Originally her melody derives from Kunshan zone of Jiangsu province therefore it has been named Kunshan melody before, Revised: 15 October 2019 now Kunqu also known as Kunju, which means Kunqu opera. This paper Accepted: 21 October 2019 mainly focuses on the development of Kunqu in the past 100 years and the Published Online: 31 October 2019 influence of historical social and humanistic changes behind the special era on Kunqu, and compares the attitudes of scholars of different schools Keywords: of thought in different eras to Kunqu and the social public to compare and analyze the degree of love of Kunqu. Kunqu Last hundred years Development Inuence 1. Introduction opera have been developed on the basis of Kunqu. It is the most complete type of drama in the history of Chinese The original name of Kunqu is “tune of KunShan”, is opera, the biggest feature is the lyrical and delicate move- the ancient Chinese opera intonation type of drama, now ments, the combination of singing and dancing is inge- known as the “Kun drama”. Originated from the Yuan nious and harmonious ,in the costumes and make-up, the Dynasty (the middle of the 14th century), it’s a traditional generals have various kinds of costumes, the civil servants Chinese culture and art of the Han ethnic group. -

Call for Chinese Opera with National "Temperament

2016 3rd International Symposium on Engineering Technology, Education and Management (ISETEM 2016) ISBN: 978-1-60595-382-3 Call for Chinese Opera with National “Temperament and Character”—Thinking about Development of Chinese Opera Xiuling Zheng1 Abstract The birth and development of Chinese opera are generally divided into five stages: the budding stage, the foundation stage, the exploration stage, the stagnation stage, the breakthrough and development stage. Nowadays, from the script to musical composition, from opera singer to all kinds of talents training, the development of Chinese opera should be adhere to the soul of Chinese culture, adhere to the national temperament and character, and also should adhere to be loved by the masses, can accept the idea and bloom its unique dazzling brilliance in the world opera stage. Keywords: the Development of Chinese Opera; National “Temperament and Character”; Personnel Training 1. INTRODUCTION The development of Chinese opera has experienced several stages as follows. The budding stage (1919-1942): Influenced by the “five four” New Culture Movement and In order to meet the needs of the patriotic struggle against imperialism, small repertoire has been produced.in which, children's song and dance drama The Sparrow and the Child produced by Li Jinhui is generally regarded as the first Chinese opera works. The foundation stage (1942-1956): Take the new yangko dance movement occurred after Yanan Forum on literature and art as starting point, a large number of yangge opera have been produced, which opened the way for the creation of the new opera. Yangge opera Brothers and Sisters Reclaim the Wasteland (1943), Husband and Wife Learn Characters (1944) were produced, and so on. -

Representing Talented Women in Eighteenth-Century Chinese Painting: Thirteen Female Disciples Seeking Instruction at the Lake Pavilion

REPRESENTING TALENTED WOMEN IN EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY CHINESE PAINTING: THIRTEEN FEMALE DISCIPLES SEEKING INSTRUCTION AT THE LAKE PAVILION By Copyright 2016 Janet C. Chen Submitted to the graduate degree program in Art History and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. ________________________________ Chairperson Marsha Haufler ________________________________ Amy McNair ________________________________ Sherry Fowler ________________________________ Jungsil Jenny Lee ________________________________ Keith McMahon Date Defended: May 13, 2016 The Dissertation Committee for Janet C. Chen certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: REPRESENTING TALENTED WOMEN IN EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY CHINESE PAINTING: THIRTEEN FEMALE DISCIPLES SEEKING INSTRUCTION AT THE LAKE PAVILION ________________________________ Chairperson Marsha Haufler Date approved: May 13, 2016 ii Abstract As the first comprehensive art-historical study of the Qing poet Yuan Mei (1716–97) and the female intellectuals in his circle, this dissertation examines the depictions of these women in an eighteenth-century handscroll, Thirteen Female Disciples Seeking Instructions at the Lake Pavilion, related paintings, and the accompanying inscriptions. Created when an increasing number of women turned to the scholarly arts, in particular painting and poetry, these paintings documented the more receptive attitude of literati toward talented women and their support in the social and artistic lives of female intellectuals. These pictures show the women cultivating themselves through literati activities and poetic meditation in nature or gardens, common tropes in portraits of male scholars. The predominantly male patrons, painters, and colophon authors all took part in the formation of the women’s public identities as poets and artists; the first two determined the visual representations, and the third, through writings, confirmed and elaborated on the designated identities. -

The Dialectics of Virtuosity: Dance in the People's Republic of China

The Dialectics of Virtuosity: Dance in the People’s Republic of China, 1949-2009 by Emily Elissa Wilcox A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Joint Doctor of Philosophy with the University of California, San Francisco in Medical Anthropology of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Xin Liu, Chair Professor Vincanne Adams Professor Alexei Yurchak Professor Michael Nylan Professor Shannon Jackson Spring 2011 Abstract The Dialectics of Virtuosity: Dance in the People’s Republic of China, 1949-2009 by Emily Elissa Wilcox Joint Doctor of Philosophy with the University of California, San Francisco in Medical Anthropology University of California, Berkeley Professor Xin Liu, Chair Under state socialism in the People’s Republic of China, dancers’ bodies became important sites for the ongoing negotiation of two paradoxes at the heart of the socialist project, both in China and globally. The first is the valorization of physical labor as a path to positive social reform and personal enlightenment. The second is a dialectical approach to epistemology, in which world-knowing is connected to world-making. In both cases, dancers in China found themselves, their bodies, and their work at the center of conflicting ideals, often in which the state upheld, through its policies and standards, what seemed to be conflicting points of view and directions of action. Since they occupy the unusual position of being cultural workers who labor with their bodies, dancers were successively the heroes and the victims in an ever unresolved national debate over the value of mental versus physical labor. -

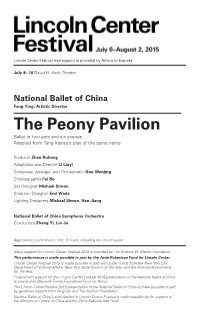

National Ballet of China Feng Ying, Artistic Director the Peony Pavilion Ballet in Two Acts and Six Scenes Adapted from Tang Xianzu’S Play of the Same Name

07-08 Peony_Gp 3.qxt 6/29/15 2:42 PM Page 1 Lincoln Center Festival lead support is provided by American Express July 8 – 10 David H. Koch Theater National Ballet of China Feng Ying, Artistic Director The Peony Pavilion Ballet in two acts and six scenes Adapted from Tang Xianzu’s play of the same name Producer Zhao Ruheng Adaptation and Director Li Liuyi Composer, Arranger, and Orchestrator Guo Wenjing Choreographer Fei Bo Set Designer Michael Simon Costume Designer Emi Wada Lighting Designers Michael Simon, Han Jiang National Ballet of China Symphony Orchestra Conductors Zhang Yi, Liu Ju Approximate performance time: 2 hours, including one intermission Major support for Lincoln Center Festival 2015 is provided by The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation. This performance is made possible in part by the Josie Robertson Fund for Lincoln Center. Lincoln Center Festival 2015 is made possible in part with public funds from the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs, New York State Council on the Arts, and the National Endowment for the Arts. Endowment support for the Lincoln Center Festival 2015 presentation of the National Ballet of China is provided by Blavatnik Family Foundation Fund for Dance. The Lincoln Center Festival 2015 presentation of the National Ballet of China is made possible in part by generous support from Yang Lan and The Joelson Foundation. National Ballet of China’s participation in Lincoln Center Festival is made possible by the support of the Ministry of Culture of China and the China National Arts Fund. 07-08 Peony_Gp 3.qxt 6/29/15 2:42 PM Page 2 LINCOLN CENTER FESTIVAL 2015 THE PEONY PAVILION July 8, 2015, at 8:00 p.m. -

How I Enjoyed the Peony Pavilion!

FEATURE How I Enjoyed The Peony Pavilion! By Chia-Hui Shih I enjoyed the performance of The Peony Pavilion so much that I wrote of my experiences with the show in two parts: first my overall impression as a layman and then my appreciation of the performance on each of the three days that the show lasted. Part I: A Layman’s Experience On September 22 to 24, I watched The Peony Pavilion at the Barclay Theater in Irvine, Calif. It was presented by a Chinese Kunqu opera company from Suzhou, Jiangsu Province. Tang Xian Zu (the Ming Dynasty, 1550- 1616) wrote the libretti, originally consisting of 55 acts. I have never seen a Kunqu production, nor even heard any recital of Kunqu. My closer encounter with the play came some twenty years The melodies (if they could be called ago when I read a play written by Bai Xian Yong melodies, more like tones) in Kunqu are quite (the producer of The Peony Pavilion) named different from those in the popular Jingju (Peking “Visiting a Garden, Startled in a Dream”. It was Opera), are more monotonous—at least to the based on one episode of The Peony Pavilion. untrained ears of mine. On the other hand, the non-singing parts, such as the movement of eyes, hands, and arms; walking styles of men and women; and the dialogue were quite similar to those in Jingju. Actually I had expected that the spoken lines would be the dialect of Suzhou, but it turned out to be a mixture of Mandarin and some Jiangsu dialects, including that of Suzhou.