Robertson Crusoe: Tony Maggs, South Africa's Forgotten GP Ace

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Altbüron LU 16

Altbüton LU Altbüron LU 16. August 2009 4. Bergprüfung für historische Sport- und Rennwagen Für Sie am Start: Infos unter: Biland! Waltisperg www.race-inn.ch 09.00 bis 17.00 Markus Eintrit't: Fr. 12.- Kinder bis 14 Jahre gratis Bösiger Jacques Cornu Robert Grogg Nee! Jani- Porsche ZenblJm Schil\ll1ach Bad Herzlich willkommen in Altbüron liebe Besucherinnen und Besucher liebe Teilnehmerinnen und Teilnehmer Als hätten w ir das stürmische Gewitter vorausgesehen, das unsere Wirtschaft gerade durchschüttelt, planten wir schon früh die Umstellung des bisherigen Zweijahrestaktes für unsere Veranstaltung. Und damit bekommt das Jahr 2009 einen willkommenen EriebnisbonU5, welcher d"e vi elen Unsicherheiten und Sorgen für ein paar Stunden ver- gessen lässt. Denn schon zum vierten Mal dürfen wir im schönen Altbüron einzigartige Rennwagen und von einst vorführen und geniessen. Dafür bedanken wir uns bei den Gemeindebehörden und den Einwohnerinnen und Einwohnern von Altbür0 . Wir hören oft von den Teilnehmenden, wie gastfreundlich und nett sie in Altbüro rn aufgenommen worden sind, und wie sehr sie sich freuen, ein nächstes Mal wieder hie dabei zu sein. Genauso erleben wir es als Organisatoren, man spürt richtig, dass wir mit nserer Szene hier willkommen sind. Unser Dank geht aber aue an die zuständigen Kantonsbehörden. Insbesondere an das Amt für Umwelt und E ergie (uwe) und an die Kantonspolizei Luzern, Bei ihnen haben wir für alle Veranstaltungen nicht nur die alles entscheidende Zustimmung erhalten, nein, wir durften stet auf echte Unterstützung zählen. Ein Dank gehört aUCh\ ns.er. n Helfern und Gästen, welche dann die bewilligte Vera I Wir brauchen sie geoau so wie di.e Fahrerinnen und mit ihrEm frisch aufpolierten Rennfahr· zeugen aller Ma und"beleben, Erneut haben wir die Ehre, I und 'I lebe KolleginnenI und Kolle- gen, zu begrüSSen. -

A Catalogue of Motoring & Motor Racing Books April 2021

A catalogue of Motoring & Motor Racing Books April 2021 Picture This International Limited Spey House, Lady Margaret Road, Sunningdale, UK Tel: (+44) 7925 178151 [email protected] All items are offered subject to prior sale. Terms and Conditions: Condition of all items as described. Title remains with Picture This until payment has been paid and received in full. Orders will be taken in strict order of receipt. Motoring & Motor Racing Books Illustrations of all the books in this catalogue can be found online at: picturethiscollection.com/products/books/books-i/motoringmotorracing/en/ SECTION CONTENTS: 01-44 AUTO-BIOGRAPHIES & BIOGRAPHIES 45-67 ROAD AND RACING CARS 68-85 RACES, CIRCUITS, TEAMS AND MOTOR RACING HISTORY 86-96 MOTOR RACING YEARBOOKS 97-100 LONDON-SYDNEY MARATHON, 1968 101-111 PRINCES BIRA & CHULA 112-119 SPEED AND RECORDS 120-130 BOOKS by and about MALCOLM CAMPBELL 131-142 TOURING AND TRAVELS AUTO-BIOGRAPHIES & BIOGRAPHIES [in alphabetical order by subject] 1. [SIGNED] BELL, Derek - My Racing Life Wellingborough: Patrick Stephens, 1988 First edition. Autobiography written by Derek Bell with Alan Henry. Quarto, pp 208. Illustrated throughout with photographs. Blue cloth covered hard boards with silver lettering to the spine; in the original dust jacket which has been price clipped. SIGNED and inscribed “ _________ my best wishes | Derek Bell | 15.7.03”. Bell won at Le Mans five times with Porsche as well as the Daytona 24 three times and was World Sports Car Champion twice in the mid 1980’s. Fine condition book in a price clipped but otherwise Fine jacket. [B5079] £85 2. -

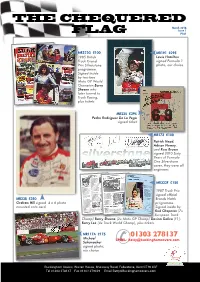

The Chequered Flag

THE CHEQUERED March 2016 Issue 1 FLAG F101 MR322G £100 MR191 £295 1985 British Lewis Hamilton Truck Grand signed Formula 1 Prix Silverstone photo, our choice programme. Signed inside by two-time Moto GP World Champion Barry Sheene who later turned to Truck Racing, plus tickets MR225 £295 Pedro Rodriguez De La Vega signed ticket MR273 £100 Patrick Head, Adrian Newey, and Ross Brawn signed 2010 Sixty Years of Formula One Silverstone cover, they were all engineers MR322F £150 1987 Truck Prix signed official MR238 £350 Brands Hatch Graham Hill signed 4 x 6 photo programme. mounted onto card Signed inside by Rod Chapman (7x European Truck Champ) Barry Sheene (2x Moto GP Champ) Davina Galica (F1), Barry Lee (4x Truck World Champ), plus tickets MR117A £175 01303 278137 Michael EMAIL: [email protected] Schumacher signed photo, our choice Buckingham Covers, Warren House, Shearway Road, Folkestone, Kent CT19 4BF 1 Tel 01303 278137 Fax 01303 279429 Email [email protected] SIGNED SILVERSTONE 2010 - 60 YEARS OF F1 Occassionally going round fairs you would find an odd Silverstone Motor Racing cover with a great signature on, but never more than one or two and always hard to find. They were only ever on sale at the circuit, and were sold to raise funds for things going on in Silverstone Village. Being sold on the circuit gave them access to some very hard to find signatures, as you can see from this initial selection. MR261 £30 MR262 £25 MR77C £45 Father and son drivers Sir Jackie Jody Scheckter, South African Damon Hill, British Racing Driver, and Paul Stewart. -

The Last Road Race

The Last Road Race ‘A very human story - and a good yarn too - that comes to life with interviews with the surviving drivers’ Observer X RICHARD W ILLIAMS Richard Williams is the chief sports writer for the Guardian and the bestselling author of The Death o f Ayrton Senna and Enzo Ferrari: A Life. By Richard Williams The Last Road Race The Death of Ayrton Senna Racers Enzo Ferrari: A Life The View from the High Board THE LAST ROAD RACE THE 1957 PESCARA GRAND PRIX Richard Williams Photographs by Bernard Cahier A PHOENIX PAPERBACK First published in Great Britain in 2004 by Weidenfeld & Nicolson This paperback edition published in 2005 by Phoenix, an imprint of Orion Books Ltd, Orion House, 5 Upper St Martin's Lane, London WC2H 9EA 10 987654321 Copyright © 2004 Richard Williams The right of Richard Williams to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN 0 75381 851 5 Printed and bound in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, St Ives, pic www.orionbooks.co.uk Contents 1 Arriving 1 2 History 11 3 Moss 24 4 The Road 36 5 Brooks 44 6 Red 58 7 Green 75 8 Salvadori 88 9 Practice 100 10 The Race 107 11 Home 121 12 Then 131 The Entry 137 The Starting Grid 138 The Results 139 Published Sources 140 Acknowledgements 142 Index 143 'I thought it was fantastic. -

Historic Grand Prix Zandvoort 2017 Historische Auto Ren C Lub

Historic Grand Prix Zandvoort 2017 Historische Auto Ren C lub HGPCA Race for Pre 1961 and Pre 1966 Grand Prix Cars 1 - 3 September 2017 Result of Qualifying Zandvoort GP - 4307 mtr. Pos Nbr Name / Entrant Car Cls PIC Fastest In Gap Diff Laps Km/h 1 122 Peter Horsman Lotus 18/21 P1 1961 12 1 1:54.889 8 9 134.96 2 25 Andy Middlehurst Lotus 25 R4 1962 11 1 1:55.196 12 0.307 0.307 12 134.60 John Bowers 3 10 William Nuthall Cooper T53 1960 7b 1 1:56.609 7 1.720 1.413 10 132.97 Giorgio Marchi 4 3 Barry Cannell Brabham BT11A 1964 12 2 1:58.351 7 3.462 1.742 9 131.01 5 2 Rod Jolley Lister Jaguar Monza GP 1958 7b 2 1:58.507 6 3.618 0.156 9 130.84 6 37 Eddy Perk Heron F1 1960 10 1 1:59.572 6 4.683 1.065 11 129.67 7 66 Sid Hoole C ooper T66 F1 1963 11 2 2:00.510 8 5.621 0.938 10 128.66 8 7 Max Blees Brabham BT7A 1963 12 3 2:01.918 7 7.029 1.408 11 127.18 9 4 Andrew Beaumont Lotus 18 915 1961 12 4 2:03.088 8 8.199 1.170 8 125.97 10 69 Mister John of B Lola Mk 4 BRGP 42 1962 11 3 2:05.264 4 10.375 2.176 9 123.78 11 15 Tom Dark Cooper T51 1960 7b 3 2:05.734 8 10.845 0.470 8 123.32 12 16 Marc Valvekens Aston Martin DBR4/4 1959 7a 1 2:06.135 6 11.246 0.401 11 122.93 13 132 Larry Kinch Lotus 32 Tasman 1964 12 5 2:07.301 8 12.412 1.166 8 121.80 14 36 Erik Staes Lotus 18/21 P2 1962 10 2 2:07.438 8 12.549 0.137 9 121.67 15 80 Nick Taylor Lotus 18 914 1961 10 3 2:07.613 10 12.724 0.175 11 121.50 16 21 Ian Nuthall Alta F2 1952 5 1 2:07.661 8 12.772 0.048 11 121.46 17 42 James Willis Cooper T45 1958 9 1 2:08.105 8 13.216 0.444 8 121.04 18 47 Brian Jolliffe Cooper T45 1958 9 2 2:08.165 6 13.276 0.060 8 120.98 19 8 Tony Ditheridge Cooper T45 1958 9 3 2:08.187 6 13.298 0.022 8 120.96 20 19 Paul Grant Cooper Bristol Mk 2 1953 5 2 2:08.275 8 13.386 0.088 11 120.87 21 11 C harles Nearburg Brabham BT11 1964 11 4 2:08.324 4 13.435 0.049 6 120.83 22 34 John Bussey Cooper T43 1957 7c 1 2:08.981 6 14.092 0.657 8 120.21 Fastest time : 1:54.889 in lap 8 by nbr. -

Grand Prix De Monaco Junior

GRAND PRIX DE MONACO JUNIOR 13.05.1961 - Monte Carlo 2 x 16 + 24 Runden á 3,145 km = 2 x 50,32 km + 75,48 km STARTERLISTE 52 Ludwig Fischer Ludwig Fischer Hartmann DKW 54 Gerhard Mitter Autohaus Mitter Lotus 18 DKW 56 Herbert Ott Herbert Ott BRW DKW 58 "Jupp Schmitz" Scuderia Colonia Lotus 18 Ford 60 Brian Gubby Brian Gubby Lotus 18 Ford 62 Steve Ouvaroff Competition Cars of Australia Ausper T3 Ford 64 Curt Bardi-Barry Ecurie Vienne Cooper T56 Ford 66 Rolf Markl Ecurie Vienne Cooper T56 Ford 68 Peter Carpenter London Road Garage Lotus 18 Fiat 70 Yves Dussaud Yves Dussaud Dalbo Simca 72 Henri Grandsire Ecurie Edger Lotus 20 Ford 74 Louis Pons Ecurie Edger Lotus 18 Ford 76 Ralph B.de Laforest Racing Team RBL Osca Maserati 78 Rene Abbal Scuderia Madunina Stanguellini Fiat 80 Adrien Bec Squadra Francia Stanguellini Fiat 82 Jacques Cales Scuderia Madunina Stanguellini Fiat 84 Andre Rolland Scuderia Madunina Stanguellini Fiat 86 Jack Pitcher Team Alexis Alexis Mk3 Ford 88 Philip Robinson Team Alexis Alexis Mk3 Ford 90 Bob Hicks Caravelle Engineering Caravelle Mk3 Ford 92 John Whitmore John Whitmore Lotus 18 BMC 94 Chris Andrews Empire Racing Team Cooper T56 Ford 96 Ian Raby Empire Racing Team Cooper T56 Ford 98 John Brown George Henrotte Team Lotus 18 Ford 100 Brian Whitehouse George Henrotte Team Lola MK3 Ford 102 David Piper David Piper Lotus 20 Ford 104 Bernie Ecclestone Elva Racing Team Elva 200 Ford 106 Harry Epps Harry Epps Elva 200 Ford 108 Peter Ashdown Lola Equipe Lola MK3 Ford 110 John Hine Lola Equipe Lola MK3 Ford 112 Richard Prior -

Eccellenze Meccaniche Italiane

ECCELLENZE MECCANICHE ITALIANE. MASERATI. Fondatori. Storia passata, presente. Uomini della Maserati dopo i Maserati. Auto del gruppo. Piloti. Carrozzieri. Modellini Storia della MASERATI. 0 – 0. FONDATORI : fratelli MASERATI. ALFIERI MASERATI : pilota automobilistico ed imprenditore italiano, fondatore della casa automobilistica MASERATI. Nasce a Voghera il 23/09/1887, è il quarto di sette fratelli, il primo Carlo trasmette la la passione per la meccanica ALFIERI, all'età di 12 anni già lavorava in una fabbrica di biciclette, nel 1902 riesce a farsi assumere a Milano dalla ISOTTA FRASCHINI, grazie all'aiuto del fratello Carlo. Alfieri grazie alle sue capacità fa carriera e alle mansioni più umili, riesce ad arrivare fino al reparto corse dell'azienda per poi assistere meccanicamente alla maccina vincente della Targa FLORIO del 1908, la ISOTTA lo manda come tecnico nella filiale argentina di Buenos Aires, poi spostarlo a Londra, e in Francia, infine nel 1914 decide, affiancato dai suoi fratelli. Ettore ed Ernesto, di fondare la MASERAT ALFIERI OFFICINE, pur rimanendo legato al marchio ISOTTA-FRASCHINI, di cui ne cura le vetture da competizione in seguito cura anche i propulsori DIATTO. Intanto però, in Italia scoppia la guerra e la sua attività viene bloccata. Alfieri Maserati, in questo periodo, progetta una candela di accensione per motori, con la quale nasce a Milano la Fabbrica CANDELE MASERATI infine progetta un prototipo con base telaio ISOTTA- FRASCHINI, ottenendo numerose vittorie, seguirà la collaborazione con la DIATTO, infine tra il 1925/26, mesce la mitica MASERATI TIPO 26, rivelandosi poi, un'automobile vincente. Il 1929 sarà l'anno della creazione di una 2 vettura la V43000, con oltre 300 CV, la quale raggiungerà i 246 Km/ h, oltre ad altre mitiche vittorie automobilistiche. -

The Mexican Grand Prix 1963-70

2015 MEXICAN GRAND PRIX • MEDIA GUIDE 03 WELCOME MESSAGE 04 MEDIA ACCREDITATION CENTRE AND MEDIA CENTRE Location Maps Opening Hours 06 MEDIA CENTRE Key Staff Facilities (IT • Photographic • Telecoms) Working in the Media Centre 09 PRESS CONFERENCE SCHEDULE 10 PHOTOGRAPHERS’ SHUTTLE BUS SCHEDULE 11 RACE TIMETABLE 15 USEFUL INFORMATION Airline numbers Rental car numbers Taxi companies 16 MAPS AND DIAGRAMS Circuit with Media Centre Media Centre layout Circuit with corner numbers Photo positions map Hotel Maps 22 2015 FIA FORMULA ONE™ WORLD CHAMPIONSHIP Entry List Calendar Standings after round 16 (USA) (Drivers) Standings after round 16 (USA) (Constructors) Team & driver statistics (after USA) 33 HOW IT ALL STARTED 35 MEXICAN DRIVERS IN THE WORLD CHAMPIONSHIP 39 MÉXICO IN WORLD CHAMPIONSHIP CONTEXT 40 2015 SUPPORT RACES 42 BACKGROUNDERS BIENVENIDO A MÉXICO! It is a pleasure to welcome you all to México as we celebrate our country’s return to the FIA Formula 1 World Championship calendar. Twice before, from 1963 to 1970 and from 1986 to 1992, México City has been the scene of exciting World Championship races. We enjoy a proud heritage in the sport: from the early brilliance of the Rodríguez brothers, the sterling efforts of Moisés Solana and Héctor Rebaque to the modern achievements of Esteban Gutíerrez and Sergio Pérez, Mexican drivers have carved their own names in the history of the sport. A few of you may have been here before. You will find many things the same – yet different. The race will still take place in the parkland of Magdalena Mixhuca where great names of the past wrote their own page in Mexican history, but the lay-out of the 21st-century track is brand-new. -

Orange Times Issue 2

The Orange Times Bruce McLaren Trust June / July 2014, Issue #2 Farewell Sir Jack 1926 - 2014 Along with the motorsport fraternity worldwide I was extremely saddened to th hear of Sir Jack’s recent passing on the 19 May. The McLaren family and Jack have shared a wonderful life-long friendship, starting with watching his early racing days in New Zealand, then Pop McLaren purchasing the Bobtail Cooper from Jack after the NZ summer racing season of 1957. For the following season of 1958, Jack made the McLaren Service Station in Remuera his base and brought the second Cooper with him from the UK for Bruce to drive in the NZIGP which culminated in Bruce being awarded the Celebrating 50 Years of “Driver to Europe”. Jack became his mentor and close friend and by 1959 McLaren Racing Bruce joined him as teammate for the Cooper Racing Team. The rest, as we say, is history but the friendship lived on and the BM Trust Following on from their Tasman Series was delighted to host Jack in New Zealand for a week of motorsport memories success, the fledgling BMMR Team set about in 2003 with Jack requesting that the priority of the trip was to be a visit to their very first sports car race with the Zerex see his “NZ Mum” Ruth McLaren, who, by then, was a sprightly 97 years old. th Special – on April 11 1964 at Oulton Park and I shared a very special hour with the two of them together and the love and this was a DNF/oil pressure. -

47. Avd-Oldtimer-Grand-Prix 2019 NEW Avd-Oldtimer-Grand-Prix Gmbh & Co OHG Goldsteinstraße 237, 60528 Frankfurt/Main 9

47. AvD-Oldtimer-Grand-Prix 2019 NEW AvD-Oldtimer-Grand-Prix GmbH & Co OHG Goldsteinstraße 237, 60528 Frankfurt/Main 9. - 11. August 2019 / Nürburgring, 4638 m Reg.-No.: 155/2019 R6 - Historic Grand Prix Cars bis 1965 Result Qualifying Started: 37 Qualified: 33 Not Qualified: 4 Not Started: 5 Pos. No. Cl. Entrant | Team Car Laps Best time Average fasted lap Driver, City, Nation, Licence Sponsor-Card Interval GAP time 13Class 12 Brabham BT11A 12 1:57.407 142.213 kph Cannell Barry, GB 11:49:04 210Class 7b Cooper T53 91:58.491 140.912 kph Nuthall William, GB 01.084 +01.084 11:45:34 317Class 12 Cooper T 79 10 1:58.595 140.788 kph Gans Michael, CH 01.188 +00.104 11:30:16 422Class 12 Lotus 18/21 11 1:58.828 140.512 kph Horsman Peter, GB 01.421 +00.233 11:48:04 520Class 7a Lotus 16 365 10 2:00.237 138.866 kph Folch-Rusinol Joaquin, ES 02.830 +01.409 11:45:37 67Class 12 Brabham BT7A 11 2:02.186 136.651 kph Blees Max, DE 04.779 +01.949 11:41:58 791Class 9 Cooper T71/73 82:02.847 135.915 kph Drake Chris, GB 05.440 +00.661 11:50:22 818Class 7b Lotus 18 372 10 2:03.167 135.562 kph Chisholm John, GB 05.760 +00.320 11:50:47 930Class 8 Scarab Offenhauser 52:03.214 135.511 kph Bronson Julian, GB 05.807 +00.047 11:36:34 10 51 Class 7b Cooper T51 11 2:03.257 135.463 kph Dark Tom, GB 05.850 +00.043 11:41:57 11 50 Class 12 Cooper T53 10 2:04.795 133.794 kph Goetze Wulf, DE 07.388 +01.538 11:45:29 12 53 Class 10 Lotus 44 F23 82:05.315 133.239 kph Buhofer Philipp, CH 07.908 +00.520 11:36:40 13 15 Class 7b Cooper T45/51 10 2:06.500 131.991 kph Matzelberger -

Thistle November 2011 Letter from the Editor Calendar of Events Ian Skone-Rees Nov

the histle ’ s S o c i e t y t n d r e w o f L o s A A S t . n g e November 2011 T h e l e s a message from John E. Lowry, FSA Scot President. Seaside 2011 St. Andrew's Societies in all corners of 9th Highland Games have the civilized world maintain a calendar of a special Scottish flavour. activities in keeping with the interests of their membership. Our venerable 80 year old club November 30th is St Late rain on Thursday tries for a balance between tradition and contemporary Andrew's Day in Scotland. suggested that for the first The patronage of the saint in keeping with our diverse membership—and that is a time in the history of the also covers fishmongers, tall order considering active memberships that reach back over half of Games clan row may be gout, singers, sore our history! But even with our history and the fine record of charitable moved indoors and the throats, spinsters, activities that make us so proud, we are mere babes when it comes to heavy athletics would maidens, old maids and other cities and their Societies. San Francisco 1846, Alexandria, Virginia become a series of mud women wishing to 1760, Boston 1659, New York 1756.One quick note from a time when wrestling matches. become mothers. But just But Friday dawned with blue Andrew Carnegie was president of SASNY, Carnegie asked his dear friend who was Saint Andrew skies, warm sun, and a gentle and how did he become Sam Clemens to come down and visit these "mortals" and speak at that ocean breeze. -

First 2017 F1s * 1:20 Brabham BT52 * Delage Test Build * 1:24 2017 LM Winner * Lancia D50 History 08-2017 NEWS Classic Touring Cars Hot Ferraris

* First 2017 F1s * 1:20 Brabham BT52 * Delage Test Build * 1:24 2017 LM Winner * Lancia D50 History 08-2017 NEWS Classic Touring Cars Hot Ferraris In December last year a special exhibition took place in Tokyo to celebrate the fiftieth anniversary of Ferrari’s first sales in Japan. A major feature of the event was the unveiling of a special new car, the J50, based on the 488 and In this issue we see two new releases from Beemax and they have plenty to be built in a run of just ten examples. If you aren’t fortunate enough to have more of interest going forward, The latest updates from this young company been on the select list for this magnificent looking machine, you can still own are on touring car subjects with the Group A Eggenberger Volvo 240 Turbo one as BBR have announced that they are to produce hand builts in both 1:43 (AOSVOLVO) which will offer the choice of ETC or Macau decal versions. An (BBRC208) and 1:18 (BBP18156). ideal companion to Tamiya’s BMW 635 CSi and Hasegawa’s recently re-issued Another new Ferrari announced at the recent Frankfurt motorshow is the Jaguar XJS (HAS20305) and like those subjects, one which will offer plenty of Portofino, a front-engined coupe/convertible to replace the California T. Both scope for aftermarket decals. BBR and MR Collection/Looksmart have been quick to announce this in 1:43 and 1:18. BBR will be offering roof down (BBRC207/BBP18155) and roof up op- tions (BBRC209/BBP18157) in numerous colours and Looksmart have sent us first images of their closed version in 1:43 MRCLS48( 0 - see front cover) and the sister MR Collection range will be catering for collectors of 1:18 (MRCFE023).