The Brotherhood of Timber Workers Struggle for Recognition in the Deep South: a Time When the Law Should Be Broken

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

International Support for Starbucks Workers

NLRB strips more In November We Remember workers of labor rights workers’ history & martyrs Working “supervisors” lose IWW founder William Trautmann, right to unionize, engaged in Brotherhood of Timber Workers, concerted activity on job 4 Victor Miners’ Hall, and more 5-8 Industrial International support for Starbucks workers As picket lines and other actions reach new Starbucks locations across the United States and the world every week, the coffee giant has told workers it is raising starting pay in an effort to blunt unionization efforts. In Chicago, where workers at a Logan Worker Square store demanded IWW union recogni- tion August 29, Starbucks has raised starting pay from $7.50 an hour to $7.80. After six months, Chicago baristas who receive favor- able performance reviews will make $8.58. Picket lines went up at Paris Starbucks OFFICIAL NEWSPAPER OF THE In New York City, where Starbucks or- anti-union campaign. UAW Local 2320 in ganizing began, baristas will make $9.63 an Brooklyn has told Starbucks that its members INDUSTRIAL WORKERS OF THE WORLD hour after six months on the job and a favor- will not drink their coffee until the fired November 2006 #1689 Vol. 103 No. 10 $1.00 / 75 p able performance review. Senior baristas will unionists are reinstated. Several union locals, receive only a ten-cent raise to discourage student groups and the National Lawyers long-term employment. Similar raises are Guild have declared they are boycotting Star- being implemented across the country. bucks in solidarity with the fired workers. Talkin’ Union Meanwhile, the National Labor Relations In England, Manchester Wobblies pick- B Y N I C K D R I E dg ER, WOBBLY D ispatC H Board continues its investigation into the fir- eted a Starbucks in Albert Square Sept. -

Revolution by the Book

AK PRESS PUBLISHING & DISTRIBUTION SUMMER 2009 AKFRIENDS PRESS OF SUMM AK PRESSER 2009 Friends of AK/Bookmobile .........1 Periodicals .................................51 Welcome to the About AK Press ...........................2 Poetry/Theater...........................39 Summer Catalog! Acerca de AK Press ...................4 Politics/Current Events ............40 Prisons/Policing ........................43 For our complete and up-to-date AK Press Publishing Race ............................................44 listing of thousands more books, New Titles .....................................6 Situationism/Surrealism ..........45 CDs, pamphlets, DVDs, t-shirts, Forthcoming ...............................12 Spanish .......................................46 and other items, please visit us Recent & Recommended .........14 Theory .........................................47 online: Selected Backlist ......................16 Vegan/Vegetarian .....................48 http://www.akpress.org AK Press Gear ...........................52 Zines ............................................50 AK Press AK Press Distribution Wearables AK Gear.......................................52 674-A 23rd St. New & Recommended Distro Gear .................................52 Oakland, CA 94612 Anarchism ..................................18 (510)208-1700 | [email protected] Biography/Autobiography .......20 Exclusive Publishers CDs ..............................................21 Arbeiter Ring Publishing ..........54 ON THE COVER : Children/Young Adult ................22 -

Anarchist Pedagogies: Collective Actions, Theories, and Critical Reflections on Education Edited by Robert H

Anarchist Pedagogies: Collective Actions, Theories, and Critical Reflections on Education Edited by Robert H. Haworth Anarchist Pedagogies: Collective Actions, Theories, and Critical Reflections on Education Edited by Robert H. Haworth © 2012 PM Press All rights reserved. ISBN: 978–1–60486–484–7 Library of Congress Control Number: 2011927981 Cover: John Yates / www.stealworks.com Interior design by briandesign 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 PM Press PO Box 23912 Oakland, CA 94623 www.pmpress.org Printed in the USA on recycled paper, by the Employee Owners of Thomson-Shore in Dexter, Michigan. www.thomsonshore.com contents Introduction 1 Robert H. Haworth Section I Anarchism & Education: Learning from Historical Experimentations Dialogue 1 (On a desert island, between friends) 12 Alejandro de Acosta cHAPteR 1 Anarchism, the State, and the Role of Education 14 Justin Mueller chapteR 2 Updating the Anarchist Forecast for Social Justice in Our Compulsory Schools 32 David Gabbard ChapteR 3 Educate, Organize, Emancipate: The Work People’s College and The Industrial Workers of the World 47 Saku Pinta cHAPteR 4 From Deschooling to Unschooling: Rethinking Anarchopedagogy after Ivan Illich 69 Joseph Todd Section II Anarchist Pedagogies in the “Here and Now” Dialogue 2 (In a crowded place, between strangers) 88 Alejandro de Acosta cHAPteR 5 Street Medicine, Anarchism, and Ciencia Popular 90 Matthew Weinstein cHAPteR 6 Anarchist Pedagogy in Action: Paideia, Escuela Libre 107 Isabelle Fremeaux and John Jordan cHAPteR 7 Spaces of Learning: The Anarchist Free Skool 124 Jeffery Shantz cHAPteR 8 The Nottingham Free School: Notes Toward a Systemization of Praxis 145 Sara C. -

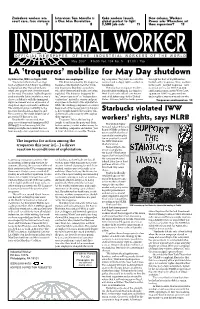

'Troqueros' Mobilize for May Day Shutdown

Zimbabwe workers win Interview: Tom Morello is Coke workers launch New column: Workers court case, face violence a One Man Revolution global protest to fight Power asks Wherefore art 3 8 3,500 job cuts 11 thou supervisor? 13 IndustrialO F F I C I A L N E W S P A P E R O F THE INDUSTRIAL Worker W O R K E R S O F T H E W O RLD May 2007 #1695 Vol. 104 No. 5 $1.00 / 75p LA ‘troqueros’ mobilize for May Day shutdown By Gideon Dev, IWW Los Angeles GMB Truckers are employees ing companies. They have no collective through the Port of LA/LB and are Truckers in the Port of Los Ange- The drive for action by the troqueros contract and no legal right to collective hauled out by troqueros. Many workers les/Long Beach (LA/LB) are mobilizing troqueros (the Spanish word for truck- bargaining. in the ports –not just troqueros– have to repeat last May Day’s shut down, ers) this year is that they, as workers The situation facing port truckers no union and no say. Of the 25,000 when over 90 per cent of trucks stayed who drive international trade, are being is particularly striking in Los Angeles. odd longshoremen on the West Coast, off the road. The action, led by the port’s exploited. The fiction of troqueros be- West Coast ports unload over 80 per 14,000 are ILWU—9,400 members predominantly Latino workforce, was a ing “owner-operators” or “independent cent of all Asian cargo to the United and roughly 4,000 non-members who show of solidarity with the immigrant contractors” instead of carrier and port States. -

Workers, an Affiliation of the Ber Trust Papers Raise the Howl of "Anarchy," Industrial Workers of the World, Have Against the I

SABOTAGE WILL SPIKE CAPITALISM'S GUNS. IMMEDIATE DEMANDS: v THE GOAL: ASIX HOUR DAY. Organization 4 Is Power A FREE RACE. ONE DOLLAR AN HOUR. IN A FREE WORLD. THE VOICE EOPLE "AN INJURY TO ONE IS AN INJURY TO ALL." VOLUME II "ll'i •l(;tllT' NEW ORLEANS, LOUISIANA, THURSDAY, SEPTEIMBER II, 1913 "TurTH CONQUERS" NUMBR 36 Take Ye Notice. AU Locals and individuals owing THE VOICE for bundle or- ders, PLEASE RUSH REMITTANCES. Also don't forget that we are forced to pay our printing and other bills EVERY TWO WEEKS, so send us all you can spare dur- ing the month and do not wait for statement. Itwill take not very much work and cash to make THE VOICE safe and we ask all our friends to pitch in and help us out of this hole by making a special drive for INDIVIDUAL SUBSCRIBERS. If you want to make any donations toward maintaining the pa- r_- il!! per, ye a editor will be glad to receive it, but be SURE to send all Brdr money intended for the "PRESS FUND" to Secretary Jay Smith, Box 78, Alexandria, La.,for otherwise and so-help-me-Bob ~E" I it will be swiped for the "Maintenance Fund" if you send it to ye under- S signe. Yours to win, COVINGTON HALL. Lumber Trust Pleads Guilty, Grabow Massacre Intended From Beginning. "American Lumberman's" Hoast Proves All Union Ever Charged. Says the "American Lumberman": eied from the beginning, we guess the "Reports from Louisiana say that world will know what to think when the activities of the Brotherhood of tlthis same sheet and all other Lum- But One More Word To Write-REVOLUTION. -

Anarchist Periodicals in English Published in the United (1833–1955) States (1833–1955): an Annotated Guide, Ernesto A

Anarchist Periodicals REFERENCE • ANARCHIST PERIODICALS Longa in English In the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, dozens of anarchist publications appeared throughout the United States despite limited fi nancial resources, a pestering and Published in censorial postal department, and persistent harassment, arrest, and imprisonment. the United States Such works energetically advocated a stateless society built upon individual liberty and voluntary cooperation. In Anarchist Periodicals in English Published in the United (1833–1955) States (1833–1955): An Annotated Guide, Ernesto A. Longa provides a glimpse into the doctrines of these publications, highlighting the articles, reports, manifestos, and creative works of anarchists and left libertarians who were dedicated to An Annotated Guide propagandizing against authoritarianism, sham democracy, wage and sex slavery, Anarchist Periodicals in English Published in the United States and racial prejudice. Nearly 100 periodicals produced throughout North America are surveyed. Entries include title; issues examined; subtitle; editor; publication information, including location and frequency of publication; contributors; features and subjects; preced- ing and succeeding titles; and an OCLC number to facilitate the identifi cation of (1833–1955) owning libraries via a WorldCat search. Excerpts from a selection of articles are provided to convey both the ideological orientation and rhetorical style of each newspaper’s editors and contributors. Finally, special attention is given to the scope of anarchist involvement in combating obscenity and labor laws that abridged the right to freely circulate reform papers through the mail, speak on street corners, and assemble in union halls. ERNESTO A. LONGA is assistant professor of law librarianship at the University of New Mexico School of Law. -

IWW Records, Part 3 1 Linear Foot (2 MB) 1930-1996, Bulk 1993-1996

Part 1 Industrial Workers of the World Collection Papers, 1905-1972 92.3 linear feet Accession No. 130 L.C. Number MS 66-1519 The papers of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) were placed in the Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs in February of 1965, by the Industrial Workers of the World. Other deposits have been made subsequently. Over the turn of the century, the cause of labor and unionism had sustained some hard blows. High immigration, insecurity of employment and frequent economic recessions added to the problems of any believer in unionism. In January, 1905 a group of people from different areas of the country came to Chicago for a conference. Their interest was the cause of labor (viewed through a variety of political glasses) and their hope was somehow to get together, to start a successful drive for industrial unionism rather than craft unionism. A manifesto was formulated and a convention called for June, 1905 for discussion and action on industrial unionism and better working class solidarity. At that convention, the Industrial Workers of the World was organized. The more politically-minded members dropped out after a few years, as the IWW in general wished to take no political line at all, but instead to work through industrial union organization against the capitalist system. The main beliefs of this group are epitomized in the preamble to the IWW constitution, which emphasizes that the workers and their employers have "nothing in common." They were not anarchists, but rather believed in a minimal industrial government over an industrially organized society. -

The Socialist Party in Dixie, 1892-1920

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 1-1-1999 Rebels of the New South : the Socialist Party in Dixie, 1892-1920. Brad A. Paul University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1 Recommended Citation Paul, Brad A., "Rebels of the New South : the Socialist Party in Dixie, 1892-1920." (1999). Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014. 1269. https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1/1269 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. REBELS OF THE NEW SOUTH: THE SOCIALIST PARTY IN DIXIE, 1892-1920 A Dissertation Presented by BRAD A. PAUL Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfilhnent of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY September 1999 The University of Massachusetts/Five College Graduate Program in History 1999 (£) Copyright by Bradley Alan Paul All Rights Reserved REBELS OF THE NEW SOUTH: THE SOCIALIST PARTY IN DIXIE, 1892-1920 A Dissertation Presented by BRAD A. PAUL Approved as to style and content by: Bruce Laurie, Chair Department of History To the Memory of Eva Florence Potts (1912-1998) ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Over the past several years my personal and professional debts have far exceeded any reasonable line credit. of On so many occasions 1 have enjoyed the good fortune of being in the just the right place to benefit from the guidance and inspiration of a wonderful collection of friends, mentors, and colleagues. -

Melvyn Dubofsky WE SHALL BE

Melvyn Dubofsky WE SHALL BE ALL A History of the Industrial Workers of the World Edited by Joseph A. McCartin Cover: A typical IWW hall in the Washington State timber region, 1917. Digital edition: C. Carretero Transmit: Confederación Sindical Solidaridad Obrera http://www.solidaridadobrera.org/ateneo_nacho/biblioteca.html Contents EDITOR’S INTRODUCTION I. A SETTING FOR RADICALISM, 1877-1917 II. THE URBAN-INDUSTRIAL FRONTIER, 1890-1905 III. THE CLASS WAR ON THE INDUSTRIAL FRONTIER, 1894-1905 IV. FROM “PURE AND SIMPLE UNIONISM” TO REVOLUTIONARY RADICALISM V. THE IWW UNDER ATTACK, 1905-7 VI. THE IWW IN ACTION, 1906-8 VII. IDEOLOGY AND UTOPIA: THE SYNDICALISM OF THE IWW VIII. THE FIGHT FOR FREE SPEECH, 1909-12 IX. STEEL, SOUTHERN LUMBER, AND INTERNAL DECAY, 1909-12 X. SATAN’S DARK MILLS: LAWRENCE, 1912 XI. SATAN’S DARK MILLS: PATERSON AND AFTER XII. BACK TO THE WEST, 1913-16 XIII. MINERS, LUMBERJACKS, AND A REORGANIZED IWW, 1916 XIV. THE CLASS WAR AT HOME AND ABROAD, 1914-17 XV. EMPLOYERS STRIKE BACK XVI. DECISION IN WASHINGTON, 1917-18 XVII. COURTROOM CHARADES, 1918-19 XVIII. DISORDER AND DECLINE, 1918-24 XIX. REMEMBRANCE OF THINGS PAST: THE IWW LEGACY BIBLIOGRAPHIC ESSAY EDITOR’S INTRODUCTION Very few books in American social or labor history have stood the test of time as well as this one. More than thirty years after its publication in 1969, Melvyn Dubofsky’s history of that hardy band of working-class radicals, the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), remains the definitive account of its subject. This book’s endurance is all the more remarkable considering how the field of labor history has changed since its publication. -

Building the Southern Tenant Farmers' Union

REVOLT IN THE FIELDS: BUILDING THE SOUTHERN TENANT FARMERS’ UNION IN THE OLD SOUTHWEST By MATTHEW F. SIMMONS A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2019 © 2019 Matthew F. Simmons To my spouse, Vivian ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The author wishes to thank his dissertation chair, Dr. Paul Ortiz, for his unflagging support and always timely advice throughout the course of this project. I also extend a special thank you to the other members of my dissertation committee: Dr. William Link, Dr. Matthew Jacobs, and Dr. Sharon Austin. Dr. Michael Honey deserves special recognition for his willingness to serve as an off-campus, external member of the dissertation committee. I am grateful to my parents for teaching me the value of education early in life and providing constant support and encouragement. Finally, I offer an especially large thank to my wonderful wife Vivian, whose willingness to assist me in any way possible insured the timely completion of this project. 4 TABLE OF CONTENTS page ACKNOWLEDGMENTS .................................................................................................. 4 ABSTRACT ..................................................................................................................... 6 CHAPTER 1 DEVIL’S BREW: RACE, LABOR, AND THE DREAM OF LANDED INDEPENDENCE ..................................................................................................... 8 2 HARDEST -

Green Corn Rebellion Trials

University of Arkansas ∙ System Division of Agriculture [email protected] ∙ (479) 575-7646 An Agricultural Law Research Article Treasonous Tenant Farmers and Seditious Sharecroppers: The 1917 Green Corn Rebellion Trials by Nigel Anthony Sellars Originally published in OKLAHOMA CITY UNIVERSITY LAW REVIEW 27 OK. CITY UNIV. L. REV. 1097 (2002) www.NationalAgLawCenter.org TREASONOUS TENANT FARMERS AND SEDITIOUS SHARECROPPERS: THE 1917 GREEN CORN REBELLION TRIALS NIGEL ANTHONY SELLARS* I. In August 2, 1917, war broke out in the former Creek and Seminole Nations lands along the South Canadian River. 1 Searching for draft resisters, the Seminole County sheriff and his deputy were ambushed near the Little River. 2 The attackers were African-American tenant * Nigel Anthony Sellars, a former journalist, holds the doctorate in history from the University of Oklahoma (1994). His articles have appeared in The Historian and The Chronicles of Oklahoma, and he is the author of Oil, Wheat & Wobblies: The Industrial Workers ofthe World in Oklahoma, 1905-1930 (University of Oklahoma Press, 1998). In 2002, he received the Muriel H. Wright Award from the Oklahoman Historical Society for his article on the 1918 Spanish flu epidemic in Oklahoma. He is currently assistant professor of history at Christopher Newport University in Newport News, Virginia. I. See Class Union Members Make up Outlaw Mob, TULSA DAILY WORLD, Aug. 4, 1917, at I; Whole Region Aflame Following the Attempted Assassination of Sheriff Gaul and Deputy Cross, SHAWNEE DAILY NEWS-HERALD, Aug. 3, 1917, at I; "War" Breaks Out in Seminole County: W.e. U's Get Naughty and Take to Warpath; But they are Wiser Now; WEWOKA CAPITAL-DEMOCRAT, Aug. -

Download File

The Point of Destruction: Sabotage, Speech, and Progressive-Era Politics Rebecca H. Lossin Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy under the Executive Committee of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2020 © 2020 Rebecca H. Lossin All Rights Reserved Abstract The Point of Destruction: Sabotage, Speech, and Progressive-Era Politics Rebecca H. Lossin Strike waves in the late nineteenth century United States caused widespread property destruction, but strike leaders did not suggest threats to employer property as a comprehensive strategy until the I.W.W. adopted a deliberate program of sabotage. Contrary to historical consensus, sabotage was an intellectually coherent and politically generative response to progressive, technocratic dreams of frictionless social cooperation that would have major consequences for the labor movement. This dissertation treats sabotage as a significant contribution to the intellectual debates that were generated by labor conflict and rapid industrialization and examines its role in shaping federal labor policy. It contends that the suppression of sabotage staked out the limits of acceptable speech and the American political imagination. Table of Contents ! Introduction: The Limits of Change ........................................................................................... 1 Chapter 1: No Interests in Common: Sabotage as Structural Analysis .............................. 14 1.1 The Critique of Property....................................