Provenance #1 Provenance #1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Royal Tropical Institute Annual Report 2016

Royal Tropical Institute Annual Report 2016 1 Contents Preface 4 Health 6 SED & Gender 16 Intercultural Professionals 24 Hospitality 30 Real Estate 38 Financial annual report 44 Social annual report 48 Corporate Governance 50 KIT’s Mission Boards & Council 54 Our mission is to enhance the positive impact of agencies, governments and corporations on sustainable development in low- and middle-income countries. For that purpose, we refer to the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG’s) as a general framework for action. We achieve this by generating evidence and applied knowledge for the practical implementation of socio-economic change and global health care, together with our partners. Our knowledge is disseminated through advising, teaching, convening and publishing. Our historical premises Our patron: in Amsterdam serve as a global host and a campus for international knowledge H.M. Queen Máxima exchange, whereby we aspire to promote intercultural cooperation. 2 Preface For KIT, 2016 has been a positive year marked by remarkable progress in all the areas in which we are active. This year we formulated our 2020 strategy, establishing KIT as a cohesive hybrid entity, in which the for-profit business units (KIT Hospitality and KIT Intercultural Professionals) support financially the research and educational programmes of the not-for-profit units (KIT Health and KIT Sustainable Economic Development & Gender). As one KIT, together with our clients and partners, we strive for sustainable impact in the areas of gender, health and economic development, in pursuit of the SDGs. Together, we collaborate under the seven strategic values of inclusion, impact, sustainability, independence, transparency, diversity and equality. -

Rules for the Contest BALI – Behind the Scenes with Djoser Travel

Rules for the contest BALI – Behind the Scenes with Djoser Travel 1. The contest to accompany the exhibition BALI – Behind the scenes runs from Thursday 13th February 2020 from 16.00 through Sunday 10th January 2021 17.00. 2. Only people aged 18 and over are eligible to take part. 3. Each visitor is entitled to take part in the competition by filling out a digital entry form at the competition desk at the Tropenmuseum. Participation is limited to one entry form per person. 4. Only fully-completed forms will be taken into consideration. These digital documents remain the property of the Tropenmuseum. No prints will be issued. 5. To be eligible to participate, people must have visited Amsterdam’s Tropenmuseum during the contest period. The museum, located at Linnaeusstraat 2 in Amsterdam, is part of the Nationaal Museum van Wereldculturen Foundation. 6. The following people are excluded from taking part: employees, interns, voluntary workers, temporary staff, freelancers and all others who have or have had a working relationship of some kind – including a provision of services agreement – with the Nationaal Museum van Wereldculturen Foundation or Djoser during the duration of the contest. 7. The Tropenmuseum retains the right to end the competition before 10th January 2021 without reason and thus to award no prize without having to inform participants. 8. The winner will be named by the Tropenmuseum’s brand manager and online marketeer in the two weeks after the exhibition has finished, by Friday 29th January 2021 at the latest. The competition draw will be executed according to software 3rd party Draw Service by the RANDOM.org website. -

Hermanus Goijers

Een Rapport Van De Genealogie Van HERMANUS GOIJERS Gecreërd op 30 april 2018 "The Complete Genealogy Reporter" © 2006-2013 Nigel Bufton Software under license to MyHeritage.com Family Tree Builder INHOUD 1. NAKOMELINGEN 2. DIRECTE RELATIES 3. INDIRECTE VERWANTSCHAP over EMMA THEUNIS 4. INDIRECTE VERWANTSCHAP over SUZANNA PAULINA ZINDEL 5. INDIRECTE VERWANTSCHAP over MARINA DE JONG 6. INDIRECTE VERWANTSCHAP over SYLVIA GEERTRUIDA JOHANNA PRINS 7. INDIRECTE VERWANTSCHAP over BERNULPHUS JOHANNES LOS 8. STAMBOMEN 9. INDEX VAN PLAATSEN 10. INDEX VAN DATA 11. INDEX VAN INDIVIDUEN 1. NAKOMELINGEN Hermanus Goijers111 +Ida Mignon112 Jozef Anton Johan Goijers (ongehuwd)107 Franciscus Goijers108 +Catharina Maria Johanna Pico109 Catharina Cornelia Maria Goijers102 Alexander Franciscus Goijers103 Cornelis Petrus Goijers104 +Emma Theunis105 Johanna Cornelia Catharina Goijers94 +Arthur Erich Max Ballin95 Johanna Emma Henriëtte Ballin68 +Frits Brandenburg69 Mireïlle Brandenburg39 ...(1) +Eli Gholam70 Michel Gholam41 Heinz Adolf Ballin71 +Annemaria Kayser-Petterson72 Markus Ballin43 Christof Ballin44 Patricia Ballin45 ...(2) Johannes Hubertus Ballin73 +Pamela Onbekend74 Jennifer Ballin47 Henriëtte Johanna Goijers96 Frans Hendrik Willem Goijers97 +Suzanna Paulina Zindel98 Jerome Goijers75 +Marina de Jong76 Jeffrey Goijers48 ...(3) Saskia Goijers50 ...(4) Enid Goijers77 Anke Goijers79 Cornelis Johannes Goijers99 +Laura Böck100 Erik Charles Goijers81 +Baps Cop82 Laura Goijers52 ...(5) Glenn Goijers54 ...(6) Irma Goijers83 Robert Carl Goijers84 +Nanny Grace -

Hermanus Goijers

Een Rapport Van De Genealogie Van HERMANUS GOIJERS Gecreërd op 12 januari 2014 "The Complete Genealogy Reporter" © 2006-2013 Nigel Bufton Software under license to MyHeritage.com Family Tree Builder INHOUD 1. NAKOMELINGEN 2. DIRECTE RELATIES 3. INDIRECTE VERWANTSCHAP over EMMA THEUNIS 4. INDIRECTE VERWANTSCHAP over SUZANNA PAULINA ZINDEL 5. INDIRECTE VERWANTSCHAP over MARINA DE JONG 6. INDIRECTE VERWANTSCHAP over SYLVIA GEERTRUIDA JOHANNA PRINS 7. INDIRECTE VERWANTSCHAP over BERNULPHUS JOHANNES LOS 8. STAMBOMEN 9. INDEX VAN PLAATSEN 10. INDEX VAN DATA 11. INDEX VAN INDIVIDUEN 1. NAKOMELINGEN Hermanus Goijers107 +Ida Mignon108 Jozef Anton Johan Goijers (ongehuwd)103 Franciscus Goijers104 +Catharina Maria Johanna Pico105 Catharina Cornelia Maria Goijers98 Alexander Franciscus Goijers99 Cornelis Petrus Goijers100 +Emma Theunis101 Johanna Cornelia Catharina Goijers90 +Arthur Erich Max Ballin91 Johanna Emma Henriëtte Ballin64 +Frits Brandenburg65 Mireïlle Brandenburg36 ...(1) +Eli Gholam66 Michel Gholam38 Heinz Adolf Ballin67 +Annemaria Kayser-Petterson68 Markus Ballin40 Christof Ballin41 Patricia Ballin42 ...(2) Johannes Hubertus Ballin69 +Pamela Onbekend70 Jennifer Ballin44 Henriëtte Johanna Goijers92 Frans Hendrik Willem Goijers93 +Suzanna Paulina Zindel94 Jerome Goijers71 +Marina de Jong72 Jeffrey Goijers45 ...(3) Saskia Goijers47 ...(4) Enid Goijers73 Anke Goijers75 Cornelis Johannes Goijers95 +Laura Böck96 Erik Charles Goijers77 +Baps Cop78 Laura Goijers49 ...(5) Glenn Goijers51 ...(6) Irma Goijers79 Robert Carl Goijers80 +Nanny Grace -

View Exhibition Brochure

1 Renée Cox (Jamaica, 1960; lives & works in New York) “Redcoat,” from Queen Nanny of the Maroons series, 2004 Color digital inket print on watercolor paper, AP 1, 76 x 44 in. (193 x 111.8 cm) Courtesy of the artist Caribbean: Crossroads of the World, organized This exhibition is organized into six themes by El Museo del Barrio in collaboration with the that consider the objects from various cultural, Queens Museum of Art and The Studio Museum in geographic, historical and visual standpoints: Harlem, explores the complexity of the Caribbean Shades of History, Land of the Outlaw, Patriot region, from the Haitian Revolution (1791–1804) to Acts, Counterpoints, Kingdoms of this World and the present. The culmination of nearly a decade Fluid Motions. of collaborative research and scholarship, this exhibition gathers objects that highlight more than At The Studio Museum in Harlem, Shades of two hundred years of history, art and visual culture History explores how artists have perceived from the Caribbean basin and its diaspora. the significance of race and its relevance to the social development, history and culture of the Caribbean: Crossroads engages the rich history of Caribbean, beginning with the pivotal Haitian the Caribbean and its transatlantic cultures. The Revolution. Land of the Outlaw features works broad range of themes examined in this multi- of art that examine dual perceptions of the venue project draws attention to diverse views Caribbean—as both a utopic place of pleasure and of the contemporary Caribbean, and sheds new a land of lawlessness—and investigate historical light on the encounters and exchanges among and contemporary interpretations of the “outlaw.” the countries and territories comprising the New World. -

VOC in East Indies 1600 – 1800 the Path to Dominance

MASARYK UNIVERSITY Faculty of Social Studies Department of International Relations and European Studies The Dutch Trading Company – VOC In East Indies 1600 – 1800 The Path to Dominance Master Thesis Supervisor: Author: Mgr. et Mgr. Oldřich Krpec, Ph.D Prilo Sekundiari Brno, 2015 0 Declaration I hereby declare that this thesis I submit for assessment is entirely my own work and has not been taken from the work of others save to the extent that such work has been cited and acknowledged within the text of my work. Date : Signature ………………… 1 Abstract: Since the arrival of the European in Asia, the economic condition in Asia especially in Southeast Asia has changed drastically. The European trading company such the Dutch’s VOC competing with the other traders from Europe, Asia, and local traders for dominance in the trading sphere in East Indies. In 17th century, the Dutch’s VOC gained its golden age with its dominance in East Indies. The purpose of this thesis is to find out what was the cause of the VOC success during its time. Keywords: VOC, Dutch, Company, Politics, Economy, Military, Conflicts, East Indies, Trade, Spices, Dominance Language used: English 2 Acknowledgements: I would like to thank my supervisor, Mgr. et Mgr. Oldřich Krpec, Ph.D., Prof. Dr. Djoko Suryo for all of his advices, matur nuwun... My friends; Tek Jung Mahat, and Weronika Lazurek. Thank you.... Prilo Sekundiari 3 Table of Contents Glossary________________________________________________________6 Introduction_____________________________________________________8 1. Background and Historical Setting 1.1. Geographical Condition___________________________________12 1.1.1. Sumatera ______________________________________________13 1.1.2. Kalimantan____________________________________________ 15 1.1.3. -

Jaar in Beeld 2018

De burgemeester van Leiden, Henri Lenferink, en de ambassadeur van Japan, Z.E. de heer Hiroshi Inomata, onthullen het kamerscherm van Keiga Kawahara. Deze aankoop vormt het sleutelstuk van de Japancollectie. 2018 IN CIJFERS WE BLIJVEN GROEIEN Een rij cijfers om trots op te zijn; niet in de laatste plaats 423.447 150 bezoekers voor het Tropenmuseum, Afrika Museum publieksprogramma’s aangeboden op de hoge waarderingscijfers en Museum Volkenkunde. Het op twee na hoogste bezoekersaantal ooit voor de musea samen die we van onze bezoekers ontvangen. 1981 54.000 nieuwe objecten in de collectie opgenomen leerlingen ontvangen in de drie musea 530 8.9 objecten uitgeleend t.b.v. tentoonstellingen is het gemiddelde waarderingscijfer dat het in andere musea Tropenmuseum Junior krijgt van de bezoekers Zowel voor primair onderwijs als voortgezet onderwijs bieden wij de keuze uit bijna 100 programma’s. Het gemiddelde waarderingscijfer voor onze onderwijsprogramma’s is een 8,3. De tentoonstelling Sieraden in Museum Volkenkunde is met een 8,3 als rapport- cijfer zeer goed ontvangen door het publiek. Daarna is de tentoonstelling in het Afrika Museum te zien. Met dit unieke model van reizende tentoonstellingen bereiken we een groter publiek. TENTOON- STELLINGEN 20 TENTOONSTELLINGEN, Van grote publiekstrekkers ONTELBARE VERHALEN tot kleine expo’s voor de OVER MENSEN liefhebber: de diversiteit in onze tentoonstellingen toont een open blik op de wereld en nodigt de bezoeker uit na te denken over wereldburgerschap. Publieksonderzoek wijst uit dat we dit jaar -

Partnerships in Cultural Heritage

PARTNERSHIPS IN CULTURAL HERITAGE Jos van Beurden PARTNERSHIPS IN CULTURAL HERITAGE The international projects of the KIT Tropenmuseum in Amsterdam Bulletin 364 Royal Tropical Institute – Amsterdam KIT Tropenmuseum Bulletins of the Royal Tropical Institute Royal Tropical Institute (KIT) The Bulletin Series of the Royal Tropical KIT Tropenmuseum Institute (KIT) deals with current themes in Mauritskade 63 international development cooperation. 1092 AD Amsterdam, The Netherlands KIT Bulletins offer a multi-disciplinary forum Telephone: +31 (0)20 5688 414 for scientists, policy makers, managers and Telefax: +31 (0)20 5688 331 development advisors in agriculture, natural E-mail: [email protected] resource management, health, culture, history Website: www.tropenmuseum.nl and anthropology. These fields reflect the broad scope of the Royal Tropical Institute (KIT) Royal Tropical Institute’s activities. KIT Publishers P.O. Box 95001 1090 HA Amsterdam, The Netherlands About the author: Telephone: +31 (0)20 5688 272 Drs Jos van Beurden (1946) is a journalist and Telefax: +31 (0)20 5688 286 publicist. He specialises in North-South E-mail: [email protected] issues. He co-wrote Jhagrapur: Poor Peasants Website: www.kit.nl/publishers and Women in a Village in Bangladesh (Dhaka, 1998, 5th imp.), as well as From © 2005 KIT Publishers, Amsterdam, Output to Outcome? 25 Years of IOB The Netherlands Evaluations (Amsterdam, 2004). For more than a decade he has focused on the Editing: Tibbon Translation protection of cultural heritage and the illicit Cover: Grafisch Ontwerpbureau Agaatsz trade in art and antiquities. Van Beurden has BNO, Meppel, The Netherlands studied this issue in many countries and Cover photograph: Schoolchildren in Kafali, published extensively on the subject, near Cotonou, Benin, visit the mobile including Goden, Graven en Grenzen: Over exhibition L’homme et son environnement kunstroof uit Afrika, Azië en Latijns Amerika (Man and environment). -

The Post Colonial Transformation of the Tropeninstituut: How Development Aid Influenced the Direction of the Institute from 1945-1979

The Post Colonial Transformation of the Tropeninstituut: How Development Aid Influenced the Direction of the Institute from 1945-1979 Source: Visual Documentation The Royal Tropical Institute (Amsterdam 1990). Niek Lohmann MA History of International Relations, Thesis University of Amsterdam Submission date: 5 January, 2016 Supervisor: prof. dr. Elizabeth Buettner Second assessor: dr. Vincent Kuitenbrouwer Student number: 5970601 Eerste van Swindenstraat 114-2 1093GL Amsterdam [email protected] Contents Introduction 3 Chapter 1. 1945 – 1960 11 1.1 Dutch development aid in the 1940s and 1950s 11 1.2 The Tropeninstituut in the 1940s and 1950s 16 1.3 Analysis of the developments of the Tropeninstituut and Dutch development aid 22 Chapter 2. 1960 – 1970 24 2.1 Dutch development aid in the 1960s 25 2.2 The Tropeninstituut in the 1960s 29 2.3 Analysis of the developments of the Tropeninstituut and Dutch development aid 32 Chapter 3. 1970 – 1980 35 3.1 Dutch development aid in the 1970s 36 3.2 The Tropeninstituut in the 1970s 40 3.3 Analysis of the developments of the Tropeninstituut and Dutch development aid 42 Conclusion 47 Bibliography 50 2 Introduction Most visitors who come to the Netherlands arrive in Amsterdam, and many of these visitors will arrive at the Central Station, one of the oldest and busiest train stations in the country. Many will be impressed by the grandeur of this large neo-renaissance building that was completed in 1889. Few, however, will pay much attention to the peculiar sculptural works embellished in the façades. Upon closer inspection, one can see a muscular, barely dressed, humble-looking Javanese man (recognizable by his typical Javanese headscarf) greeting a bearded European-looking man. -

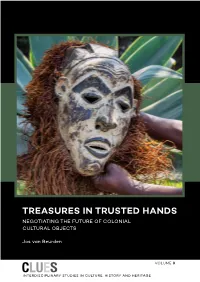

Treasures in Trusted Hands

Van Beurden Van TREASURES IN TRUSTED HANDS This pioneering study charts the one-way traffic of cultural “A monumental work of and historical objects during five centuries of European high quality.” colonialism. It presents abundant examples of disappeared Dr. Guido Gryseels colonial objects and systematises these into war booty, (Director-General of the Royal confiscations by missionaries and contestable acquisitions Museum for Central Africa in by private persons and other categories. Former colonies Tervuren) consider this as a historical injustice that has not been undone. Former colonial powers have kept most of the objects in their custody. In the 1970s the Netherlands and Belgium “This is a very com- HANDS TRUSTED IN TREASURES returned objects to their former colonies Indonesia and mendable treatise which DR Congo; but their number was considerably smaller than has painstakingly and what had been asked for. Nigeria’s requests for the return of with detachment ex- plored the emotive issue some Benin objects, confiscated by British soldiers in 1897, of the return of cultural are rejected. objects removed in colo- nial times to the me- As there is no consensus on how to deal with colonial objects, tropolis. He has looked disputes about other categories of contestable objects are at the issues from every analysed. For Nazi-looted art-works, the 1998 Washington continent with clarity Conference Principles have been widely accepted. Although and perspicuity.” non-binding, they promote fair and just solutions and help people to reclaim art works that they lost involuntarily. Prof. Folarin Shyllon (University of Ibadan) To promote solutions for colonial objects, Principles for Dealing with Colonial Cultural and Historical Objects are presented, based on the 1998 Washington Conference Principles on Nazi-Confiscated Art. -

Dissonant Heritages and Memories in Contemporary Europe

PALGRAVE STUDIES IN CULTURAL HERITAGE AND CONFLICT Dissonant Heritages and Memories in Contemporary Europe Tuuli Lähdesmäki · Luisa Passerini Sigrid Kaasik-Krogerus · Iris van Huis Palgrave Studies in Cultural Heritage and Confict Series Editors Ihab Saloul University of Amsterdam Amsterdam, Noord-Holland, The Netherlands Rob van der Laarse University of Amsterdam Amsterdam, The Netherlands Britt Baillie Centre for Urban Conficts Research University of Cambridge Cambridge, UK This book series explores the relationship between cultural heritage and confict. The key themes of the series are the heritage and memory of war and confict, contested heritage, and competing memories. The series editors seek books that analyze the dynamics of the past from the perspective of tangible and intangible remnants, spaces, and traces as well as heritage appropriations and restitutions, signifcations, museal- izations, and mediatizations in the present. Books in the series should address topics such as the politics of heritage and confict, identity and trauma, mourning and reconciliation, nationalism and ethnicity, dias- pora and intergenerational memories, painful heritage and terrorscapes, as well as the mediated reenactments of conficted pasts. Dr. Ihab Saloul is associate professor of cultural studies, founder and research vice-di- rector of the Amsterdam School for Heritage, Memory and Material Culture (AHM) at University of Amsterdam. Saloul’s interests include cultural memory and identity politics, narrative theory and visual anal- ysis, confict and trauma, Diaspora and migration as well as contempo- rary cultural thought in the Middle East. Professor Rob van der Laarse is research director of the Amsterdam School for Heritage, Memory and Material Culture (AHM), and Westerbork Professor of Heritage of Confict and War at VU University Amsterdam. -

Program Indonesian Textiles at the Tropenmuseum Book Launch

Indonesian Textiles at the Tropenmuseum by Itie van Hout The Tropenmuseum Amsterdam holds an internationally renowned collection of textiles from Indonesia. Numbering approximately 12,000 objects, the majority of these textiles were acquired during the period that Indonesia was a Dutch colony. These textiles originate from all over the archipelago, from Aceh on Sumatra, to Tanimbar in the east. A small part of the collection was made in the Netherlands for artistic or commercial reasons. Indonesian Textiles at the Tropenmuseum examines the stories of those who made and used these collections, those who collected and brought them to the Netherlands, as well as those who have studied and exhibited them. During the book launch, we will explore questions such as: what is the importance of these collections today and what do they tell us about the material worlds in which they were created and used? How might a study of these collections help us better understand Dutch colonial and scientific histories and relations? In addition, in what ways have the study of textiles in ethnographic museums related to the discipline of anthropology in general and its subfield of material culture studies? About the author: Itie van Hout is former Curator of Textiles of the Tropenmuseum, Amsterdam, and is now retired. She is the author of Batik Drawn in Wax: 200 Years of Batik Art from Indonesia in the Tropenmuseum Collection (2001) and Beloved Burden: Baby Carriers in Different Countries (2011). Program book launch starts at 14:00: 1. Opening Dr. Wayne Modest (Research Center for Material Culture) 2. Textile Collections of the Tropenmuseum Itie van Hout (Tropenmuseum) 3.