25 Years Later: What Has Changed?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Your Bus Service Is Changing

120 Constellation Bus Station Constellation Bus Station Henderson Henderson Sunset Rd Sunset Rd Ratanui St Ratanui St Meadowood Dr Meadowood Dr Unitec Waitakere Unitec Waitakere Sunset Rd Sunset Rd Swanson Rd Swanson Rd Tableau Place walkway Tableau Place walkway Mt Lebanon Lane Mt Lebanon Lane Sunset Rd Sunset Rd Swanson Rd Swanson Rd North Shore Trias Rd Trias Rd Sturges Rd Station Sturges Rd Station Jo Sunset Rd Sunset Rd Swanson Rd Swanson Rd Golf Course hn Gl Target Rd Target Rd 114 Swanson Rd 114 Swanson Rd enn Av Elm e Sunset Rd Sunset Rd Swanson Rd Swanson Rd o ple Girrahween Dr Girrahween Dr Waitakere College Waitakere College r p by ei rmark Dr e R A Rd P Albany Highway Albany Highway Swanson Rd Swanson Rd d A n Dr Westminster Christian School Westminster Christian School Mihini Rd Mihini Rd io l Rosedale t Albany ba E a Upper Harbour Dr Upper Harbour Dr Swanson Rd Swanson Rd ell L Dene Court Lane Dene Court Lane Universal Drive roundabout Universal Drive roundabout n Junior High Park st av g Rosedale South n Upper Harbour Dr Upper Harbour Dr Don Buck Rd Don Buck Rd ny o e li C J ry Kereru Grove Kereru Grove Sabot Place Sabot Place s l Park d u P Greenhithe Rd Greenhithe Rd RiverheadDon Buck Forest Rd Don Buck Rd h R nipe 175 Greenhithe Rd 175 Greenhithe Rd Helena St Helena St H e ws Rd t r tthe e R L Oak v ul Ma s Greenhithe Rd Greenhithe Rd Don Buck Rd Don Buck Rd au ig A Pa n d S rel Oak Dr S l u Upper Harbour Motorway Upper Harbour Motorway Zita Maria Drive Zita Maria Drive Dr c h l Constellation S c A a h r Greenhithe Rd -

The Waterview Connection Motorway

Waterview Connection Information Sheet THE WATERVIEW CONNECTION MOTORWAY WHEN WILL THE WATERVIEW WHAT ARE THE TRAFFIC WHAT IS THE CONNECTION OPEN TO BENEFITS OF THE WATERVIEW TRAFFIC? WATERVIEW CONNECTION? Construction is on schedule for opening in early By bridging the gap between the Southwestern CONNECTION? 2017 as planned. and Northwestern motorways, the Waterview Connection will complete Auckland’s Western Being built is 5km of 6-lane motorway Ring Route. This is a 48km motorway link from to connect State Highways 20 (the Manukau in the south to Albany in the north that Southwestern Motorway) and 16 (the WHO WILL OPERATE will bypass central Auckland. Northwestern Motorway). THE MOTORWAY? Completing the Western Ring Route has been There will be three lanes southbound and prioritised as a Road of National Significance three lanes northbound between Maioro The Well-Connected Alliance, which is building because of the contribution it will make to New Street, where S.H.20 now ends, and the the Waterview Connection, will form an alliance Zealand’s future prosperity. It will provide Auckland Great North Road interchange on S.H.16. with international tunnel controls specialists SICE NZ Ltd (Sociedad Ibérica de Construcciones with a resilient and reliable motorway network by Half of the new motorway is underground in Eléctricas) to operate and maintain the motorway reducing the region’s dependence on the single twin tunnels 2.4km long and up to 30m below for the first 10 years of its life. A team from SICE spine comprising State Highway 1 and the Auckland the surface between the Alan Wood Reserve has worked with the Well-Connected Alliance Harbour Bridge for business to business trips, in Owairaka and Waterview. -

Auckland's Strategic Public Transport Network – Lessons Learned from The

Auckland’s Strategic PT Network D Newcombe Page 0 AUCKLAND’S STRATEGIC PUBLIC TRANSPORT NETWORK – LESSONS LEARNED FROM THE BUSINESS CASE APPROACH Author/Presenter: Daniel Newcombe, MEngSt (Transportation), BPlan, MNZPI City Centre & RTN Initiatives team manager, Auckland Transport [email protected] 15th December 2016 ABSTRACT Auckland Transport (AT) is investigating how best to plan and deliver future improvements to the Strategic Public Transport Network (SPTN) to cater for Auckland’s rapidly growing population. The way this work is being undertaken is influenced by NZTA’s new Business Case Approach required for all future transport investments. This paper will outline AT’s work to date on the SPTN and how AT is using the recent Auckland Transport Alignment Project (ATAP) to strategically direct this work. The paper will also cover what AT has learned from applying the various processes contained within the Business Case Approach, how this has shaped the future programme and any wider lessons that could be applied to other transport projects. IPENZ Transportation Group Conference, Hamilton, 29 – 31 March 2017 Auckland’s Strategic PT Network D Newcombe Page 1 INTRODUCTION Auckland Transport (AT) is the road controlling authority responsible for the planning, operation and maintenance of most components of the Auckland transport system, including the public transport network (buses, trains, and ferries). The core of the public transport system is the Strategic Public Transport Network (SPTN) which consists of the heavy rail network and Northern Busway. To receive transport investment from the New Zealand Transport Agency (NZTA) for developing the SPTN and all other transport infrastructure or services, AT is required undertake a range of business cases defined under the Business Case Approach (BCA). -

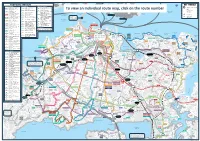

To View an Individual Route Map, Click on the Route Number

Ngataringa Bayswater PROPOSED SERVICES Bay KEY SYMBOLS FREQUENT SERVICES LOCAL SERVICES PEAK PERIOD SERVICES Little Shoal Station or key connection point Birkenhead Bay Northwestern Northwest to Britomart via Crosstown 6a Crosstown 6 extension to 101 Pt Chevalier to Auckland University services Northwestern Motorway and Selwyn Village via Jervois Rd Northcote Cheltenham Rail Line Great North Rd To viewNorthcote an individualPoint route map, click on the route number (Passenger Service) Titirangi to Britomart via 106 Freemans Bay to Britomart Loop 209 Beach North Shore Northern Express routes New North Rd and Blockhouse Bay Stanley Waitemata service Train Station NX1, NX2 and NX3 138 Henderson to New Lynn via Mangere Town Centre to Ferries to Northcote, Point Harbour City LINK - Wynyard Quarter to Avondale Peninsula Wynyard Quarter via Favona, Auckland Harbour Birkenhead, West Harbour, North City Link 309X Bridge Beach Haven and Karangahape Rd via Queen St 187 Lynfield to New Lynn via Mangere Bridge, Queenstown Rd Ferries to West Harbour, Hobsonville Head Ferry Terminal Beach Haven and Stanley Bay (see City Centre map) Blockhouse Bay and Pah Rd (non stop Hobsonville Services in this Inner LINK - Inner loop via Parnell, Greenwoods Corner to Newmarket) Services to 191 New Lynn to Blockhouse Bay via North Shore - direction only Inner Link Newmarket, Karangahape Rd, Avondale Peninsula and Whitney St Panmure to Wynyard Quarter via Ferry to 701 Lunn Ave and Remuera Rd not part of this Ponsonby and Victoria Park 296 Bayswater Devonport Onehunga -

Name Suburb Notes a Abbotleigh Avenue Te Atatu Peninsula Named C.1957. Houses Built 1957. Source: Geomaps Aerial Photo 1959

Name Suburb Notes A Abbotleigh Avenue Te Atatu Peninsula Named c.1957. Houses built 1957. Source: Geomaps aerial photo 1959. Abel Tasman Ave Henderson Named 7/8/1973. Originally named Tasman Ave. Name changed to avoid confusion with four other Auckland streets. Abel Janszoon Tasman (1603-1659) was a Dutch navigator credited with being the discoverer of NZ in 1642. Located off Lincoln Rd. Access Road Kumeu Named between 1975-1991. Achilles Street New Lynn Named between 1943 and 1961. H.M.S. Achilles ship. Previously Rewa Rewa Street before 1930. From 1 March 1969 it became Hugh Brown Drive. Acmena Ave Waikumete Cemetery Named between 1991-2008. Adam Sunde Place Glen Eden West Houses built 1983. Addison Drive Glendene Houses built 1969. Off Hepburn Rd. Aditi Close Massey Formed 2006. Previously bush in 2001. Source: Geomaps aerial photo 2006. Adriatic Avenue Henderson Named c.1958. Geomaps aerial photo 1959. Subdivision of Adriatic Vineyard, which occupied 15 acres from corner of McLeod and Gt Nth Rd. The Adriatic is the long arm of the Mediterranean Sea which separates Italy from Yugoslavia and Albania. Aetna Place McLaren Park Named between 1975-1983. Located off Heremaia St. Subdivision of Public Vineyard. Source: Geomaps aerial photo 1959. Afton Place Ranui Houses built 1979. Agathis Rise Waikumete Cemetery Named between 1991-2008. Agathis australis is NZ kauri Ahu Ahu Track Karekare Named before 2014. The track runs from a bend in Te Ahu Ahu Road just before the A- frame house. The track follows the old bridle path on a steeply graded descent to Watchman Road. -

Attachment 2

Attachme nt 2 Appendix 1 Table 1A: Auckland Transport Proposed Funded Capital Programme for AT Board approval (20th June 2018) Prioritisation Key: 1 Committed/Ring-fenced The following programme has been developed for the Regional Land Transport Plan 2018-28. Indicative project costs (nominal values, including inflation) represent the estimated cost of project/programme delivered 2 Funded by Auckland Transport, including any financial assistance from the Transport Agency unless stated otherwise. 3 Unfunded Projects carried forward from 2017/18 ($m) 2024/25 - Project Name Project Description Prioritisation Duration 2018/19 2019/20 2020/21 2021/22 2022/23 2023/24 2027/28 Albany Station P&R Extension stage 1 1 2018/19 0.5 Double Decker Network Mitigation 1 2018/19 3.7 Ormiston Town Centre Main Street Link 1 2018/19 6.9 Rail Crossing Safety Improvements 1 2018/19 0.2 Rail Crossing Separation (Phase 1B) 1 2018/19 1.9 Rail Crossing Separation (Phase 2) 1 2018/19 3.3 Projects carried forward from 2017/18 Regional Park and Ride Fund 1 2018/19 2.5 SaFE Set-up Rail Integration 1 2018/19 1.0 Takanini Station Upgrade 1 2018/19 1.1 Te Mahia Station Upgrade 1 2018/19 0.9 Wiri EMU Depot Extension (Wiri II) 1 2018/19 6.0 Other projects 1 2018/19 38.0 Committed, Ring-fenced, On-going Operational and Renewal Projects and Programmes (Alphabetical order, $m) 2024/25 - Project Name Project Description Prioritisation Duration 2018/19 2019/20 2020/21 2021/22 2022/23 2023/24 2027/28 Committed Projects and Programmes Phases 1 of the Albany park'n'ride extension to increase capacity and patronage on the Northern Albany Station P&R Extension stage 1 1 2018/19 0.8 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 Busway. -

Traffic Bulletin

TRAFFIC BULLETIN 23 February 2018 | AUCKLAND Overnight motorway closures 2 5 February – 3 March 2018 The NZ Transport Agency advises of the following closures for motorway improvements. Closures start at 9pm and finish at 5am, unless otherwise stated. Work delayed by bad weather will be completed at the next available date, prior to Friday, 2nd March 2018. Please note this Traffic Bulletin is updated every Friday. Check daily updated closure information: click here. NORTHERN MOTORWAY (SH1) Northbound lanes between Upper Harbour Highway off ramp and Oteha Valley Road on ramp, 25 February - 1 March (approx. 10:30p.m. to 5:00a.m.) Upper Harbour Highway northbound on ramp, 25 February - 1 March Greville Road northbound on ramp, 25 February - 1 March Southbound lanes between Oteha Valley Road off ramp and Upper Harbour Highway on ramp, 25 February - 1 March (approx. 10:00p.m. to 5:00a.m.) Oteha Valley Road southbound on ramp, 25 February - 1 March McClymonts Road southbound on ramp, 25 February - 1 March Greville Road southbound on ramp, 25 February - 1 March Shelly Beach Road southbound off ramp, 27 February & 1 March Curran Street northbound on ramp, 28 February Stafford Road northbound off ramp, 28 February CENTRAL MOTORWAY JUNCTION (SH1 & SH16) (SH1) Symonds Street northbound off ramp, 25 February (SH1) Symonds Street southbound on ramp, 25 February (SH1) Khyber Pass Road northbound off ramp, 25 February (SH1) Khyber Pass Road northbound off ramp, 28 February (SH1) Gillies Avenue northbound on ramp, 25 & 28 February SOUTHERN MOTORWAY (SH1) Northbound lanes between Greenlane off ramp and Gillies Avenue on ramp, 27 February (approx. -

Leighton Contractors Signs Motorway Upgrade Contract in Auckland

24 February 2014 Leighton Contractors signs motorway upgrade contract in Auckland The NZ Transport Agency and Leighton Contractors have signed a contract to upgrade a two kilometre section of Auckland’s State Highway16 (Northwestern motorway), from the St Lukes Road interchange in Western Springs to the Great North Road interchange in Waterview. Under the NZ $70 million contract, Leighton Contractors will widen the motorway from three to four lanes in each direction and make improvements to ramps and the motorway overbridge at the St Lukes Interchange. The new layout and additional lanes will relieve congestion and improve safety in the area. The project is part of the Transport Agency’s Western Ring Route, which will provide an alternative motorway link between Manukau City and Albany, bypassing Auckland’s city centre and the Auckland Harbour Bridge. Leighton Contractors New Zealand General Manager, Andrew Stevens, said: “This is a vital section of the Western Ring Route, which when complete, will significantly improve access and connectivity for Auckland’s commuters and freight carriers. “Working with the Transport Agency, we look forward to contributing our experience from similar projects both here and overseas. This project complements the work we are delivering nearby on the SH16 Causeway upgrade, as a member of the Causeway Alliance.” Leighton Contractors has been involved in a number of major road developments in recent years including the Northern Gateway Toll Road, SH20 Manukau Motorway Extension and Newmarket Viaduct replacement project. “Leighton Contractors is committed to New Zealand’s infrastructure development. Our operations here have grown steadily over the past 10 years. -

Auckland Transport Alignment Project April 2018

Auckland Transport Alignment Project April 2018 Foreword I welcome the advice provided by the Auckland Transport Alignment Project (ATAP). The ATAP package is a transformative transport programme. Investment in transport shapes our city’s development and is a key contributor to economic, social and environmental goals. The direction signalled in this update is shared by Government and Auckland Council and demonstrates our commitment to working together for a better Auckland. Auckland is facing unprecedented population growth, and over the next 30 years a million more people will call Auckland home. Growth brings opportunities but when combined with historic under- investment in infrastructure the strain on the Auckland transport system is unrelenting. Existing congestion on our roads costs New Zealand’s economy $1.3b annually. We need to do things differently to what has been done in the past. Auckland needs a transport system that provides genuine choice for people, enables access to opportunities, achieves safety, health and environmental outcomes and underpins economic development. Our aspiration must be to make sure Auckland is a world class city. Auckland’s success is important not just for Aucklanders, but for our country’s long-term growth and productivity. The Government and Auckland Council have agreed to a transformative and visionary plan. ATAP is a game-changer for Auckland commuters and the first-step in easing congestion and allowing Auckland to move freely. I believe this ATAP package marks a significant step in building a modern transport system in Auckland. ATAP accelerates delivery of Auckland’s rapid transit network, with the aim of unlocking urban development opportunities, encourages walking and cycling, and invests in public transport, commuter and freight rail and funds road improvements. -

Report of the Waterview Connection Procurement Steering Group Progressing the Waterview Connection As a Public Private Partnership

Report of the Waterview Connection Procurement Steering Group Progressing the Waterview Connection as a public private partnership An investigation of the value of a public private partnership 26 June 2008 To: The Hon Dr Michael Cullen, Minister of Finance, and the Hon Annette King, Minister of Transport. The Waterview Connection Procurement Steering Group is pleased to present our Report into progressing the Waterview Connection as a public private partnership as requested in the Terms of Reference released on 7 February 2008. Dated: 26 June 2008 Sir Brian Elwood Independent Chair Elizabeth Anderson Michael Barnett Ministry of Transport Auckland Chamber of Commerce Mike James Stephen Selwood Deputy Secretary, The Treasury New Zealand Council for Infrastructure Development Phil O’Reilly Business New Zealand Progressing the Waterview Connection as a public private partnership 1 Contents Foreword ..................................................................................................................................................................2 1. Executive summary ..........................................................................................................................................5 2. Introduction ......................................................................................................................................................8 Steering Group membership ................................................................................................................................8 The -

Enjoy Our City. Enjoy Your Life

Enjoy our city. Enjoy your life. LICENSED REAA 2008 Tuatahi continues Ockham Residential’s ambition to provide Aucklanders with homes that are well built, well located, well liked and affordable. Situated in Mt Albert with neighbouring parklands, these homes are also adjacent to the brand new Waterview Shared Path, in close proximity to Unitec’s Mt Albert campus and within walking distance of two train stations. Whether it’s urban Britomart or a link to the beautiful West Coast, our great city is only a short ride away. Tuatahi consists of three well-appointed apartment buildings surrounding a large communal garden featuring a pool and a two-level community facility. This oasis at the heart of the development offers a sense of community and connectedness for the residents. The intricate brick detailing creates a timeless and charming façade. These homes will appeal to individuals and families looking for a low maintenance secure environment. Tuatahi - Enjoy our city. Enjoy your life. DISCLAIMER; While we have taken every effort to ensure the accuracy of the information found in this document, Ockham Residential Realty Ltd can take no responsibility for 1 any errors or omissions. Purchasers are advised to complete their own due diligence on the subject property. 2 3 LICENSED REAA 2008 Why Tuatahi? Collective ambition drives change and creates possibility. Through a shared desire to improve our built environment, the Marutūāhu Iwi and Ockham Residential have created Tuatahi Apartments for Aucklanders. Tuatahi, meaning ‘The First’, represents a first – a partnership between Ockham Residential and the Marutūāhu Iwi, mana whenua of Tāmaki Makaurau. -

Construction, Operation and Maintenance of the Waterview Connection Project (The Project)

Final Report and Decision of the Board of Inquiry into the New Zealand Transport Agency Waterview Connection Proposal Produced under Section 149R of the Resource Management Act 1991 Volume 2 Conditions of Consent Published by the Board of Inquiry into the New Zealand Transport Agency Waterview Connection Proposal Publication No: EPA 25 ISBN: 978-0-478-34852-1 (print) 978-0-478-34853-8 (electronic) 978-0-478-34854-5 (CD) June 2011 FinalDesignationandConsentConditions 29June2011 Explanation The following integrated set of Conditions relates to designation and resource consents for the construction, operation and maintenance of the Waterview Connection Project (The Project). The Project includes: 1. The motorway extension of SH20 from Maioro Street (New Windsor) to connect with SH16 at the Great North Road Interchange, including two tunnels through Mt Albert / Avondale; and 2. The upgrading of the Northwestern Motorway (SH16) increasing its capacity (for private vehicles and improved bus lanes), and raising it to improve the resilience of the State highway network. The Project will take place within the designation boundaries outlined as Notice of Requirement 202 in the Auckland District Plan and as Notice of Requirement NZTA1 in the Waitakere District Plan. The majority of works of the Project falling within the designated footprint are authorised by the various designations. However, the following key areas of the Project are subject to a further Outline Plan of Works approval: 1. Northern ventilation building and stack (OPW1 – as shown on Figure DC.A); and 2. Southern ventilation building and stack (OPW2 – as shown on Figure DC.B). A number of supporting documents have been prepared for the designations and resource consents, including an Assessment of Environmental Effects, a suite of Specialist Technical Reports and a Construction Environmental Management Plan (CEMP) (a full suite of these documents and plans is set out in Condition DC.1).