Albert-Eden Heritage Survey (P.1-140)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Historic Heritage Topic Report

Historic Heritage Topic Report Drury Structure Plan August 2017 Image: Detail from Cadastral Survey of Drury 1931 (LINZ) 1 This report has been prepared by John Brown (MA) and Adina Brown (MA, MSc), Plan.Heritage Ltd. Content was also supplied by Cara Francesco, Auckland Council and Lisa Truttman, Historian. This report has been prepared for input into the Drury Structure Plan process and should not be relied upon for any other purpose. This report relies upon information from multiple sources but cannot guarantee the accuracy of that information. 1 Table of contents Contents 1. Executive summary ..................................................................................................... 4 2. Introduction ................................................................................................................. 6 2.1. Purpose ...................................................................................................................... 6 2.2. Study area .................................................................................................................. 6 3. Methodology ............................................................................................................... 8 3.1. Approach .................................................................................................................... 8 3.2. Scope .......................................................................................................................... 8 3.3. Community and iwi consultation................................................................................. -

Your Bus Service Is Changing

120 Constellation Bus Station Constellation Bus Station Henderson Henderson Sunset Rd Sunset Rd Ratanui St Ratanui St Meadowood Dr Meadowood Dr Unitec Waitakere Unitec Waitakere Sunset Rd Sunset Rd Swanson Rd Swanson Rd Tableau Place walkway Tableau Place walkway Mt Lebanon Lane Mt Lebanon Lane Sunset Rd Sunset Rd Swanson Rd Swanson Rd North Shore Trias Rd Trias Rd Sturges Rd Station Sturges Rd Station Jo Sunset Rd Sunset Rd Swanson Rd Swanson Rd Golf Course hn Gl Target Rd Target Rd 114 Swanson Rd 114 Swanson Rd enn Av Elm e Sunset Rd Sunset Rd Swanson Rd Swanson Rd o ple Girrahween Dr Girrahween Dr Waitakere College Waitakere College r p by ei rmark Dr e R A Rd P Albany Highway Albany Highway Swanson Rd Swanson Rd d A n Dr Westminster Christian School Westminster Christian School Mihini Rd Mihini Rd io l Rosedale t Albany ba E a Upper Harbour Dr Upper Harbour Dr Swanson Rd Swanson Rd ell L Dene Court Lane Dene Court Lane Universal Drive roundabout Universal Drive roundabout n Junior High Park st av g Rosedale South n Upper Harbour Dr Upper Harbour Dr Don Buck Rd Don Buck Rd ny o e li C J ry Kereru Grove Kereru Grove Sabot Place Sabot Place s l Park d u P Greenhithe Rd Greenhithe Rd RiverheadDon Buck Forest Rd Don Buck Rd h R nipe 175 Greenhithe Rd 175 Greenhithe Rd Helena St Helena St H e ws Rd t r tthe e R L Oak v ul Ma s Greenhithe Rd Greenhithe Rd Don Buck Rd Don Buck Rd au ig A Pa n d S rel Oak Dr S l u Upper Harbour Motorway Upper Harbour Motorway Zita Maria Drive Zita Maria Drive Dr c h l Constellation S c A a h r Greenhithe Rd -

![Schedule 14.1 Schedule of Historic Heritage [Rcp/Dp]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2664/schedule-14-1-schedule-of-historic-heritage-rcp-dp-142664.webp)

Schedule 14.1 Schedule of Historic Heritage [Rcp/Dp]

Schedule 14.1 Schedule of Historic Heritage [rcp/dp] Introduction The criteria in B5.2.2(1) to (5) have been used to determine the significant historic heritage places in this schedule and will be used to assess any proposed additions to it. The criteria that contribute to the heritage values of scheduled historic heritage in Schedule 14.1 are referenced with the following letters: A: historical B: social C: Mana Whenua D: knowledge E: technology F: physical attributes G: aesthetic H: context. Information relating to Schedule 14.1 Schedule 14.1 includes for each scheduled historic heritage place; • an identification reference (also shown on the Plan maps) • a description of a scheduled place • a verified location and legal description and the following information: Reference to Archaeological Site Recording Schedule 14.1 includes in the place name or description a reference to the site number in the New Zealand Archaeological Association Site Recording Scheme for some places, for example R10_709. Categories of scheduled historic heritage places Schedule 14.1 identifies the category of significance for historic heritage places, namely: (a) outstanding significance well beyond their immediate environs (Category A); or (b) the most significant scheduled historic heritage places scheduled in previous district plans where the total or substantial demolition or destruction was a discretionary or non-complying activity, rather than a prohibited activity (Category A*). This is an interim category until a comprehensive re-evaluation of these places is undertaken and their category status is addressed through a plan change process; or 1 (c) considerable significance to a locality or greater geographic area (Category B). -

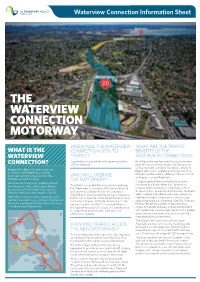

The Waterview Connection Motorway

Waterview Connection Information Sheet THE WATERVIEW CONNECTION MOTORWAY WHEN WILL THE WATERVIEW WHAT ARE THE TRAFFIC WHAT IS THE CONNECTION OPEN TO BENEFITS OF THE WATERVIEW TRAFFIC? WATERVIEW CONNECTION? Construction is on schedule for opening in early By bridging the gap between the Southwestern CONNECTION? 2017 as planned. and Northwestern motorways, the Waterview Connection will complete Auckland’s Western Being built is 5km of 6-lane motorway Ring Route. This is a 48km motorway link from to connect State Highways 20 (the Manukau in the south to Albany in the north that Southwestern Motorway) and 16 (the WHO WILL OPERATE will bypass central Auckland. Northwestern Motorway). THE MOTORWAY? Completing the Western Ring Route has been There will be three lanes southbound and prioritised as a Road of National Significance three lanes northbound between Maioro The Well-Connected Alliance, which is building because of the contribution it will make to New Street, where S.H.20 now ends, and the the Waterview Connection, will form an alliance Zealand’s future prosperity. It will provide Auckland Great North Road interchange on S.H.16. with international tunnel controls specialists SICE NZ Ltd (Sociedad Ibérica de Construcciones with a resilient and reliable motorway network by Half of the new motorway is underground in Eléctricas) to operate and maintain the motorway reducing the region’s dependence on the single twin tunnels 2.4km long and up to 30m below for the first 10 years of its life. A team from SICE spine comprising State Highway 1 and the Auckland the surface between the Alan Wood Reserve has worked with the Well-Connected Alliance Harbour Bridge for business to business trips, in Owairaka and Waterview. -

SALES TRACK RECORD City Metro Team April 2018 Sales Track Record

SALES TRACK RECORD City MEtro Team April 2018 sales track record 777-779 NEW NORTH ROAD, MT ALBERT 31 MACKELVIE STREET, GREY LYNN 532-536 PARNELL ROAD, PARNELL PRICE: $1,300,000 PRICE: $2,715,000 PRICE: $13,600,000 METHOD: Tender METHOD: Deadline Private Treaty METHOD: Tender ANALYSIS: Part Vacant, $7,103/m² land & buildings ANALYSIS: $5,645/m² on land ANALYSIS: $7,039/m² land area BROKERS: Reese Barragar BROKERS: Reese Barragar, Murray Tomlinson BROKERS: Andrew Clark, Graeme McHoull, Cam Paterson DATE: March 2018 DATE: March 2018 DATE: March 2018 VENDOR: St Albans Limited VENDOR: Telecca New Zealand Limited VENDOR: Empire Trust (Mike & Irene Rosser) sales track record 35 CHURCH STREET, ONEHUNGA 57L LIVINGSTONE STREET, GREY LYNN 62 BROWN STREET, ONEHUNGA PRICE: $1,210,000 PRICE: $515,000 PRICE: $2,700,000 METHOD: Auction METHOD: Deadline Private Treaty METHOD: Auction ANALYSIS: $4,115/m² land & building ANALYSIS: Vacant, $8,583/m2 Land & Buildings ANALYSIS: 4.62% yield BROKERS: Murry Tomlinson BROKERS: Reese Barragar, Shaydon Young BROKERS: Murry Tomlinson, Reese Barragar DATE: March 2018 DATE: March 2018 DATE: March 2018 VENDOR: Walker Trust VENDOR: Lion Rock Roast Limited VENDOR: Shanks & Holmes sales track record 69/210-218 VICTORIA STREET WEST, VICTORIA QUARTER 10 ADELAIDE STREET, VICTORIA QUARTER 60 MT EDEN ROAD, MT EDEN PRICE: $1,300,000 PRICE: $855,000 PRICE: $2,600,000 METHOD: Private Treaty METHOD: Deadline Private Treaty METHOD: Tender ANALYSIS: Vacant, $6,075/m2 land & buildings ANALYSIS: Vacant, $8,066/m² land & building ANALYSIS: -

Auckland / Matamata / Rotorua

PCM: SD15 SOUTHERN CROSS Pacific Destinations Ltd 1 Boundary Rd, Hobsonville Auckland, New Zealand Email: [email protected] Telephone: +64 9 915-8888 Facsimile: +64 9 915-8889 www.pacificdestinations.co.nz Quotation: SD15 SOUTHERN CROSS 21-22 Day 1: Arrive Auckland On arrival to Auckland Airport please make your way to the Budget Rental Car counter located within the arrivals hall to collect your Budget rental car and make your way to your accommodation. AUCKLAND - an exciting, sporting and cultural city, sprawled on a narrow isthmus, between two harbours. The Waitemata and Manukau Harbours, are a main feature of the city, along with numerous volcanic cones such as Mount Eden and Rangitoto Island. The city's many beaches, marinas and parks, make it ideal for outdoor pursuits such as yachting, rugby, cricket or a day at the beach. The Auckland metropolitan area is New Zealand's biggest city, and the population mix of European, Maori, and Pacific Islander, make Auckland the largest Polynesian city in the World. Day 2: Auckland Skytower – Sky Deck Admission Admission is included to both sky deck and the main observation deck of Sky Tower. Auckland War Memorial Museum Auckland War Memorial Museum where exciting stories of the Pacific, New Zealand’s people, and the flora and fauna and landforms of our unique islands, are told within a memorial dedicated to those who have sacrificed their lives for our country. In one of New Zealand's most outstanding historical buildings, boldly situated in the Domain - a central city pleasure garden - you encounter exhibitions that will excite you with the artistic legacy and cultures of the peoples of the Pacific; the monumental carvings, buildings, canoes and taonga (treasures) of the Maori; and the diversity of cultures which now combine to form the rich tapestry of race, nationality and creed which is modern New Zealand. -

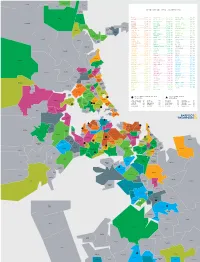

TOP MEDIAN SALE PRICE (OCT19—SEP20) Hatfields Beach

Warkworth Makarau Waiwera Puhoi TOP MEDIAN SALE PRICE (OCT19—SEP20) Hatfields Beach Wainui EPSOM .............. $1,791,000 HILLSBOROUGH ....... $1,100,000 WATTLE DOWNS ......... $856,750 Orewa PONSONBY ........... $1,775,000 ONE TREE HILL ...... $1,100,000 WARKWORTH ............ $852,500 REMUERA ............ $1,730,000 BLOCKHOUSE BAY ..... $1,097,250 BAYVIEW .............. $850,000 Kaukapakapa GLENDOWIE .......... $1,700,000 GLEN INNES ......... $1,082,500 TE ATATŪ SOUTH ....... $850,000 WESTMERE ........... $1,700,000 EAST TĀMAKI ........ $1,080,000 UNSWORTH HEIGHTS ..... $850,000 Red Beach Army Bay PINEHILL ........... $1,694,000 LYNFIELD ........... $1,050,000 TITIRANGI ............ $843,000 KOHIMARAMA ......... $1,645,500 OREWA .............. $1,050,000 MOUNT WELLINGTON ..... $830,000 Tindalls Silverdale Beach SAINT HELIERS ...... $1,640,000 BIRKENHEAD ......... $1,045,500 HENDERSON ............ $828,000 Gulf Harbour DEVONPORT .......... $1,575,000 WAINUI ............. $1,030,000 BIRKDALE ............. $823,694 Matakatia GREY LYNN .......... $1,492,000 MOUNT ROSKILL ...... $1,015,000 STANMORE BAY ......... $817,500 Stanmore Bay MISSION BAY ........ $1,455,000 PAKURANGA .......... $1,010,000 PAPATOETOE ........... $815,000 Manly SCHNAPPER ROCK ..... $1,453,100 TORBAY ............. $1,001,000 MASSEY ............... $795,000 Waitoki Wade HAURAKI ............ $1,450,000 BOTANY DOWNS ....... $1,000,000 CONIFER GROVE ........ $783,500 Stillwater Heads Arkles MAIRANGI BAY ....... $1,450,000 KARAKA ............. $1,000,000 ALBANY ............... $782,000 Bay POINT CHEVALIER .... $1,450,000 OTEHA .............. $1,000,000 GLENDENE ............. $780,000 GREENLANE .......... $1,429,000 ONEHUNGA ............. $999,000 NEW LYNN ............. $780,000 Okura Bush GREENHITHE ......... $1,425,000 PAKURANGA HEIGHTS .... $985,350 TAKANINI ............. $780,000 SANDRINGHAM ........ $1,385,000 HELENSVILLE .......... $985,000 GULF HARBOUR ......... $778,000 TAKAPUNA ........... $1,356,000 SUNNYNOOK ............ $978,000 MĀNGERE ............. -

Meet Your Franklin Local Board Candidates P4-5

6 September 2019 Issue 1317 Stephanie McLean –Harcourts Pohutukawa Coast Stephanie Mclean Licensed Agent REAA 2008. Election Sales &Marketing Specialist M 021 164 5111 Hoverd&Co. SPeCIAL special AGENTs IAN 0272859314 JENNY02040002564 Meet your NICOLETTE0277029157 Franklin Local Board candidates TING 40 p4-5 RA Y B T E E OR ON A R L MTIMBER E CO.LTD S C 292 8656 • • 19 9 79 – 201 Morton Timber Co. Ltd 226 NorthRoad, Clevedon2248 Ph 292 8656 or 021943 220 Email: [email protected] Web: www.mortontimber.co.nz Like us on Facebook to go in the draw to WIN a$150 voucher fordinneratyour INSIDE: AT proposes road repairs p2 Urban East feature p6-7 Sports news p10-11 favouritelocal restaurant GetaJumponthe Spring Market... Call EliseObern Great Smiles. P:(09) 536 7011 or (021) 182 5939 Better Health. E:[email protected] W: rwbeachlands.co.nz At Anthony Hunt Dental we have been A:81Second View Avenue, Beachlands East Tamaki proud to be serving our local community since 2011. Creating great smiles and FREE PROPERTY APPRAISAL AND better health for the whole family. MARKET UPDATE AVAILABLE NOW! Uniforms&Promotional Products FollowusonFacebook andInstagram Ray White Beachlands (09) 292 9071 [email protected] Lighthouse Real Estate Limited for specials, competitionsand giveaways 52 Papakura-Clevedon Road Licensed (REAA 2008) Cnr Smales and Springs Rds,EastTamaki-09 265 0300 www.ahdental.co.nz DEADLINES: Display advertising - 5pm Friday. Classifieds and News - midday Monday Ph: 536 5715 Email: [email protected] www.pctimes.nz 2 POHUTUKAWA COAST TIMES (6 September 2019) Guest editorial by Orere Community and Boating Association committee member Tim Greene GET IN TOUCH P: 536 5715 The last few years has seen the resi- scheme. -

Geocene-24.Pdf

Geocene Auckland GeoClub Magazine Number 24, December 2020 Editor: Jill Kenny CONTENTS Instructions on use of hyperlinks last page 19 NEW 14C RESULT CONFIRMS 28,000 YEAR OLD Elaine R. Smid, 2 – 5 MAUNGAWHAU / MT EDEN ERUPTION AGE Bruce W. Hayward, Thomas Stolberger, Roderick Wallace, Ewart Barnsley FORTY-SEVEN YEARS OF EROSION AND WEATHERING Bruce W. Hayward 6 – 7 OF LION ROCK BOMB, PIHA MAORI BAY MICROMINERALS Tim Saunderson 8 – 14 PROXY EVIDENCE FROM TAMAKI DRIVE FOR THE Bruce W. Hayward 15 – 16 LOCATION OF SUBMERGED STREAM VALLEYS BENEATH HOBSON BAY, AUCKLAND CITY THE FIRST EXPLANATION IS NOT ALWAYS THE BEST Bruce W. Hayward 17 – 18 Corresponding authors’ contact information 19 Geocene is a periodic publication of Auckland Geology Club, a section of the Geoscience Society of New Zealand’s Auckland Branch. Contributions about the geology of New Zealand (particularly northern New Zealand) from members are welcome. Articles are lightly edited but not refereed. Please contact Jill Kenny [email protected] 1 NEW 14C RESULT CONFIRMS 28,000 YEAR OLD MAUNGAWHAU / MT EDEN ERUPTION AGE Elaine R Smid1, Bruce W Hayward2, Thomas Stolberger1, Roderick Wallace1, and Ewart Barnsley3 1 The University of Auckland 2 Geomarine Research 3 City Rail Link In February 2019, City Rail Link (CRL) reported that their The large obstruction (>1 m diameter in a 2 m drill hole) micro-tunnel boring machine “Jeffie” became entangled caused Jeffie to veer off course. CRL removed the wood in a large tree at 15 m depth, approximately 50 m north fragments and pulled them to the surface (Fig. -

The Demographic Transformation of Inner City Auckland

New Zealand Population Review, 35:55-74. Copyright © 2009 Population Association of New Zealand The Demographic Transformation of Inner City Auckland WARDLOW FRIESEN * Abstract The inner city of Auckland, comprising the inner suburbs and the Central Business District (CBD) has undergone a process of reurbanisation in recent years. Following suburbanisation, redevelopment and motorway construction after World War II, the population of the inner city declined significantly. From the 1970s onwards some inner city suburbs started to become gentrified and while this did not result in much population increase, it did change the characteristics of inner city populations. However, global and local forces converged in the 1990s to trigger a rapid repopulation of the CBD through the development of apartments, resulting in a great increase in population numbers and in new populations of local and international students as well as central city workers and others. he transformation of Central Auckland since the mid-twentieth century has taken a number of forms. The suburbs encircling the TCentral Business District (CBD) have seen overall population decline resulting from suburbanisation, as well as changing demographic and ethnic characteristics resulting from a range of factors, and some areas have been transformed into desirable, even elite, neighbourhoods. Towards the end of the twentieth century and into the twenty first century, a related but distinctive transformation has taken place in the CBD, with the rapid construction of commercial and residential buildings and a residential population growth rate of 1000 percent over a fifteen year period. While there are a number of local government and real estate reports on this phenomenon, there has been relatively little academic attention to its nature * School of Environment, The University of Auckland. -

The New Zealand Gazette 1239

4 AUGUST THE NEW ZEALAND GAZETTE 1239 In Bankruptcy-In the Supreme Court Holden at Auckland Reed, Phyllis Ethel, Kingsland, Auckland, Machine Press Operator. Re~an, Lionel William, Grafton, Auckland, Contractor. Reid, Robert Bruce, Epsom, Auckland, Builder. 'NOTICE is hereby given that statements of accounts and Reilly, Richard Charles Arthur, Northcote, Bus Driver. balance sheets in respect of the undermentioned estates, Rhind, Earl Raymond, Epsom, Auckland, Baker. together with the reports of the Audit Office thereon. have been Rix, Edward vYalker, Auckland, Labourer. duly filed in the above Court; and I hereby further 'give notice Roberts, vV. A., Mount Eden, Auckland, Builder. that at the sittings of the said Court to be holden on Friday Ross, S. vV., New Lynn, Panelbeater. the 26th day of August 1955, at 10 o )clock in the forenooi{ Rowan, Albert Allen, Epsom, Auckland, Horse Trainer. or as soon thereafter as application may be heard, I intend Rowe, Arthur Charles, Avondale, Auckland, Builder. to apply for orders releasing me from. the administration of Sandison, W., Papakura, Drainlayer. the said estates. Sayes, Edwin, Auckland, Printer. Scaife, Jack Garnet, Remuera, Carpenter. Adams, Dennis, Thames, Driver. Schiavi, Alan Vvilliam, Auckland, Electrician. Albury, Gordon, Titirangi, Builder and Contractor. Scott, R. A., Auckland, Plumber. Arnold, Albert Colin, formerly of Taupo, but now of Auck Shenton, A. J., Auckland, Jewellery Dealer. land, Building Contractor. Short, George Francis, Mount Eden, Motor Mechanic. Askew,. Ian James vVemyss, Kingsland, Auckland, Motor Stevens, Bryan Howard, Auckland, Tram.wayman. Engmeer. Stewart, Raymond vVarren, Auckland, Truck Driver. Atkins, Peter Paul Joseph, Devonport, Reporter. Stoddart, James Mervyn, Mount Eden, Auckland, Salesman. -

South & East Auckland Auckland Airport

G A p R D D Paremoremo O N R Sunnynook Course EM Y P R 18 U ParemoremoA O H N R D E M Schnapper Rock W S Y W R D O L R SUNSET RD E R L ABERDEEN T I A Castor Bay H H TARGE SUNNYNOOK S Unsworth T T T S Forrest C Heights E O South & East Auckland R G Hill R L Totara Vale R D E A D R 1 R N AIRA O S Matapihi Point F W F U I T Motutapu E U R RD Stony Batter D L Milford Waitemata THE R B O D Island Thompsons Point Historic HI D EN AR KITCHENER RD Waihihi Harbour RE H Hakaimango Point Reserve G Greenhithe R R TRISTRAM Bayview D Kauri Point TAUHINU E Wairau P Korakorahi Point P DIANA DR Valley U IPATIKI CHIVALRY RD HILLSIDERD 1 A R CHARTWELL NZAF Herald K D Lake Takapuna SUNNYBRAE RD SHAKESPEARE RD ase RNZAF T Pupuke t Island 18 Glenfield AVE Takapuna A Auckland nle H Takapuna OCEAN VIEW RD kland a I Golf Course A hi R Beach Golf Course ro O ia PT T a E O Holiday Palm Beach L R HURSTMERE RD W IL D Park D V BEACH HAVEN RD NORTHCOTE R N Beach ARCHERS RD Rangitoto B S P I O B E K A S D A O Island Haven I RD R B R A I R K O L N U R CORONATION RD O E Blackpool H E Hillcrest R D A A K R T N Church Bay Y O B A SM K N D E N R S Birkdale I R G Surfdale MAN O’WAR BAY RD Hobsonville G A D R North Shore A D L K A D E Rangitawhiri Point D E Holiday Park LAK T R R N OCEANRALEIGH VIEW RD I R H E A R E PUPUKE Northcote Hauraki A 18 Y D EXMOUTH RD 2 E Scott Pt D RD L R JUTLAND RD E D A E ORAPIU RD RD S Birkenhead V I W K D E A Belmont W R A L R Hauraki Gulf I MOKO ONEWA R P IA RD D D Waitemata A HINEMOA ST Waiheke LLE RK Taniwhanui Point W PA West Harbour OLD LAKE Golf Course Pakatoa Point L E ST Chatswood BAYSWATER VAUXHALL RD U 1 Harbour QUEEN ST Bayswater RD Narrow C D Motuihe KE NS R Luckens Point Waitemata Neck Island AWAROA RD Chelsea Bay Golf Course Park Point Omiha Motorway .