Downloaded from Brill.Com10/02/2021 08:35:54PM Via Free Access

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kretanja 13-14 Engl KB.Indd

Kretanja ČASOPIS ZA PLESNU UMJETNOST Kretanja 13/14 _ 1 from Croatian stages: 09 Iva nerina Sibila Which .... ? Jelena Mihelčić Humman Error ... contents editorial: dance/ 04 art: Katja Šimunić ??? ? Maja Marjančić Anka krizmanić .... ? Maja Đurinović The Exhibition... theory: ? Katja Šimunić Three... 2 _ Kretanja 13/14 MilkoSparemblek Intro- duction ?? Maja Đurinović ?? ?? ?? Vjeran Zuppa Svjetlana Hribar Ludio doctus 2+2: Pokret je zbir svega što jesmo ?? Andreja Jeličić 77 Plesno kazalište Milka Bosiljka Perić Kempf Šparembleka u svjetlu teorije Plesati možete na glazbu, umjetnosti kao ekspresije ali i na šum, ritam, tišinu... ?? Darko Gašparović O dramaturgiji Milka Šparembleka ?? Tuga Tarle Oda ljubavi pod čizmom ideologije Kretanja 13/14 _ 3 editorial: n anticipation of the establishment of dance education at the university le- vel in Croatia, which will, according to the founders’ announcements, bring Itogether practical (i. e. classical and contemporary dance techniques) and theoretical dance studies in one institution, Kretanja (Movements), as the only Croatian journal exclusively dedicated to dance art, has from its very fi rst issue (in 2002) published a corpus of texts that can be used as a kind of basis or in- troduction into dance theory, and which should have an important place in the envisaged institution and serve as a platform for institutional and non-instituti- onal researchers of dance. Throughout issues dealing with special themes whe- re dance is positioned in relation to literature, photography, dramaturgy, fi lm or visual arts, along with translations of essays of the most important international dance theoreticians, we have introduced texts that present different examples of knowledge about dance on the path to the much needed dynamically organised dance studies, and we have also presented outstanding creations from the Croa- tian dance scene and promoted domestic authors. -

Elisabeth Epstein: Moscow–Munich–Paris–Geneva, Waystations of a Painter and Mediator of the French-German Cultural Transfer

chapter 12 Elisabeth Epstein: Moscow–Munich–Paris–Geneva, Waystations of a Painter and Mediator of the French-German Cultural Transfer Hildegard Reinhardt Abstract The artist Elisabeth Epstein is usually mentioned as a participant in the first Blaue Reiter exhibition in 1911 and the Erster Deutscher Herbstsalon in 1913. Living in Munich after 1898, Epstein studied with Anton Ažbe, Wassily Kandinsky, and Alexei Jawlensky and participated in Werefkin’s salon. She had already begun exhibiting her work in Paris in 1906 and, after her move there in 1908, she became the main facilitator of the artistic exchange between the Blue Rider artists and Sonia and Robert Delaunay. In the 1920s and 1930s she was active both in Geneva and Paris. This essay discusses the life and work of this Russian-Swiss painter who has remained a peripheral figure despite her crucial role as a mediator of the French-German cultural transfer. Moscow and Munich (1895–1908) The special attraction that Munich and Paris exerted at the beginning of the twentieth century on female Russian painters such as Alexandra Exter, Sonia Delaunay, Natalia Goncharova, and Olga Meerson likewise characterizes the biography of the artist Elisabeth Epstein née Hefter, the daughter of a doc- tor, born in Zhytomir/Ukraine on February 27, 1879. After the family’s move to Moscow, she began her studies, which continued from 1895 to 1897, with the then highly esteemed impressionist figure painter Leonid Pasternak.1 Hefter’s marriage, in April 1898, to the Russian doctor Miezyslaw (Max) Epstein, who had a practice in Munich, and the birth of her only child, Alex- ander, in March 1899, are the most significant personal events of her ten-year period in Bavaria’s capital. -

The Creative Output of Alexej Von Jawlensky (Torzhok, Russia, 1864

The creative output of Alexej von Jawlensky (Torzhok, Russia, 1864 - Wiesbaden, Germany, 1941) is dened by a simultaneously visual and spiritual quest which took the form of a recurring, almost ritual insistence on a limited number of pictorial motifs. In his memoirs the artist recalled two events which would be crucial for this subsequent evolution. The rst was the impression made on him as a child when he saw an icon of the Virgin’s face reveled to the faithful in an Orthodox church that he attended with his family. The second was his rst visit to an exhibition of paintings in Moscow in 1880: “It was the rst time in my life that I saw paintings and I was touched by grace, like the Apostle Paul at the moment of his conversion. My life was totally transformed by this. Since that day art has been my only passion, my sancta sanctorum, and I have devoted myself to it body and soul.” Following initial studies in art in Saint Petersburg, Jawlensky lived and worked in Germany for most of his life with some periods in Switzerland. His arrival in Munich in 1896 brought him closer contacts with the new, avant-garde trends while his exceptional abilities in the free use of colour allowed him to achieve a unique synthesis of Fauvism and Expressionism in a short space of time. In 1909 Jawlensky, his friend Kandinsky and others co-founded the New Association of Artists in Munich, a group that would decisively inuence the history of modern art. Jawlensky also participated in the activities of Der Blaue Reiter [the Blue Rider], one of the fundamental collectives for the formulation of the Expressionist language and abstraction. -

Auf Freiheit Zugeschnitten

Léon Bakst BEGLEITPROGRAMM BESONDERE VERANSTALTUNGEN KUNSTMUSEEN KREFELD Giacomo Balla ACCOMPANYING PROGRAM SPECIAL EVENTS KAISER WILHELM MUSEUM Vanessa Bell Edward Burne-Jones In einem umfangreichen Führungs- und Begleitprogramm werden KÜNSTLER*INNEN DER Walter Crane die vielfältigen Aspekte der Ausstellung theoretisch und praktisch KUNSTIMPULS AUSSTELLUNG Sonia Delaunay vertieft: Im Fokus stehen beispielsweise das Ausprobieren unter- Museum live erleben mit SWK und Sparkasse Krefeld, Eintritt frei ARTISTS Clotilde von Derp schiedlicher Gestaltungstechniken wie Nähen, Sticken, Batik, Buch- 1.11.2018, 17–21 Uhr IN THE EXHIBITION Isadora Duncan gestaltung, Modezeichnung oder Raumdekoration, das Entwerfen Dress-Code – Nieder mit dem Mieder Emilie Flöge utopischer und visionärer Kleidung, Fragen nach Selbst- und Fremd- Unter anderem mit einer Lesung von Margret Greiner, Autorin Mariano Fortuny bild. Innerhalb der Ausstellung entsteht ein Atelier, in dem entspre- des Buches »Auf Freiheit zugeschnitten. Emilie Flöge: Mode- Josef Hoffmann chende Workshops stattfinden. Regelmäßige öffentliche Führungen, schöpferin und Gefährtin Gustav Klimts« sowie musikalischen Ludwig von Hofmann historische Erlebnisführungen mit Lesungen, Veranstaltungen für Darbietungen aus der Zeit um 1900 Wassily Kandinsky Erwachsene, Familien und Kinder, ein Projekt für Jugendliche sowie Gustav Klimt spezielle Schulprogramme begleiten die Ausstellung. Mela Köhler HISTORISCHE ERLEBNISFÜHRUNGEN Frances Macdonald MacNair The broad accompanying program and guided tours will -

Alexander Calder James Johnson Sweeney

Alexander Calder James Johnson Sweeney Author Sweeney, James Johnson, 1900-1986 Date 1943 Publisher The Museum of Modern Art Exhibition URL www.moma.org/calendar/exhibitions/2870 The Museum of Modern Art's exhibition history— from our founding in 1929 to the present—is available online. It includes exhibition catalogues, primary documents, installation views, and an index of participating artists. MoMA © 2017 The Museum of Modern Art THE MUSEUM OF RN ART, NEW YORK LIBRARY! THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART Received: 11/2- JAMES JOHNSON SWEENEY ALEXANDER CALDER THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART, NEW YORK t/o ^ 2^-2 f \ ) TRUSTEESOF THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART Stephen C. Clark, Chairman of the Board; McAlpin*, William S. Paley, Mrs. John Park Mrs. John D. Rockefeller, Jr., ist Vice-Chair inson, Jr., Mrs. Charles S. Payson, Beardsley man; Samuel A. Lewisohn, 2nd Vice-Chair Ruml, Carleton Sprague Smith, James Thrall man; John Hay Whitney*, President; John E. Soby, Edward M. M. Warburg*. Abbott, Vice-President; Alfred H. Barr, Jr., Vice-President; Mrs. David M. Levy, Treas HONORARY TRUSTEES urer; Mrs. Robert Woods Bliss, Mrs. W. Mur ray Crane, Marshall Field, Philip L. Goodwin, Frederic Clay Bartlett, Frank Crowninshield, A. Conger Goodyear, Mrs. Simon Guggenheim, Duncan Phillips, Paul J. Sachs, Mrs. John S. Henry R. Luce, Archibald MacLeish, David H. Sheppard. * On duty with the Armed Forces. Copyright 1943 by The Museum of Modern Art, 11 West 53 Street, New York Printed in the United States of America 4 CONTENTS LENDERS TO THE EXHIBITION Black Dots, 1941 Photo Herbert Matter Frontispiece Mrs. Whitney Allen, Rochester, New York; Collection Mrs. -

Impressionist & Modern

Impressionist & Modern Art New Bond Street, London I 10 October 2019 Lot 8 Lot 2 Lot 26 (detail) Impressionist & Modern Art New Bond Street, London I Thursday 10 October 2019, 5pm BONHAMS ENQUIRIES PHYSICAL CONDITION IMPORTANT INFORMATION 101 New Bond Street London OF LOTS IN THIS AUCTION The United States Government London W1S 1SR India Phillips PLEASE NOTE THAT THERE IS NO has banned the import of ivory bonhams.com Global Head of Department REFERENCE IN THIS CATALOGUE into the USA. Lots containing +44 (0) 20 7468 8328 TO THE PHYSICAL CONDITION OF ivory are indicated by the VIEWING [email protected] ANY LOT. INTENDING BIDDERS symbol Ф printed beside the Friday 4 October 10am – 5pm MUST SATISFY THEMSELVES AS lot number in this catalogue. Saturday 5 October 11am - 4pm Hannah Foster TO THE CONDITION OF ANY LOT Sunday 6 October 11am - 4pm Head of Department AS SPECIFIED IN CLAUSE 14 PRESS ENQUIRIES Monday 7 October 10am - 5pm +44 (0) 20 7468 5814 OF THE NOTICE TO BIDDERS [email protected] Tuesday 8 October 10am - 5pm [email protected] CONTAINED AT THE END OF THIS Wednesday 9 October 10am - 5pm CATALOGUE. CUSTOMER SERVICES Thursday 10 October 10am - 3pm Ruth Woodbridge Monday to Friday Specialist As a courtesy to intending bidders, 8.30am to 6pm SALE NUMBER +44 (0) 20 7468 5816 Bonhams will provide a written +44 (0) 20 7447 7447 25445 [email protected] Indication of the physical condition of +44 (0) 20 7447 7401 Fax lots in this sale if a request is received CATALOGUE Julia Ryff up to 24 hours before the auction Please see back of catalogue £22.00 Specialist starts. -

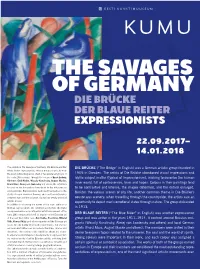

Die Brücke Der Blaue Reiter Expressionists

THE SAVAGES OF GERMANY DIE BRÜCKE DER BLAUE REITER EXPRESSIONISTS 22.09.2017– 14.01.2018 The exhibition The Savages of Germany. Die Brücke and Der DIE BRÜCKE (“The Bridge” in English) was a German artistic group founded in Blaue Reiter Expressionists offers a unique chance to view the most outstanding works of art of two pivotal art groups of 1905 in Dresden. The artists of Die Brücke abandoned visual impressions and the early 20th century. Through the oeuvre of Ernst Ludwig idyllic subject matter (typical of impressionism), wishing to describe the human Kirchner, Emil Nolde, Wassily Kandinsky, August Macke, Franz Marc, Alexej von Jawlensky and others, the exhibition inner world, full of controversies, fears and hopes. Colours in their paintings tend focuses on the innovations introduced to the art scene by to be contrastive and intense, the shapes deformed, and the details enlarged. expressionists. Expressionists dedicated themselves to the Besides the various scenes of city life, another common theme in Die Brücke’s study of major universal themes, such as the relationship between man and the universe, via various deeply personal oeuvre was scenery: when travelling through the countryside, the artists saw an artistic means. opportunity to depict man’s emotional states through nature. The group disbanded In addition to showing the works of the main authors of German expressionism, the exhibition attempts to shed light in 1913. on expressionism as an influential artistic movement of the early 20th century which left its imprint on the Estonian art DER BLAUE REITER (“The Blue Rider” in English) was another expressionist of the post-World War I era. -

Gertrud Leistikow En De Moderne, 'Duitsche' Dans. Een Biografie De Boer, J.A

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) Gertrud Leistikow en de moderne, 'Duitsche' dans. Een biografie de Boer, J.A. Publication date 2015 Document Version Final published version Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): de Boer, J. A. (2015). Gertrud Leistikow en de moderne, 'Duitsche' dans. Een biografie. General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:07 Oct 2021 Gertrud Leistikow en de moderne, 'Duitsche' dans. Een biografie Gertrud Leistikow en de moderne, 'Duitsche' dans. Een biografie ACADEMISCH PROEFSCHRIFT ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor aan de Universiteit van Amsterdam op gezag van de Rector Magnificus prof. dr. D.C. van den Boom ten overstaan van een door het College voor Promoties ingestelde commissie, in het openbaar te verdedigen in de Agnietenkapel op dinsdag 31 maart 2015, te 14.00 uur door Jacoba Adriana de Boer geboren te Meppel Promotiecommissie: Promotor: Prof. -

Mehr Mode Rn E Fü R D As Le N Ba Ch Ha Us Die

IHR LENBACHHAUS.DE KUNSTMUSEUM IN MÜNCHEN MEHR MEHR FÜR DAS MODERNE LENBACHHAUS LENBACHHAUS DIE NEUERWERBUNGEN IN DER SAMMLUNG BLAUER REITER 13 OKT 2020 BIS 7 FEB 2021 Die Neuerwerbungen in der Sammlung Blauer Reiter 13. Oktober 2020 bis 7. Februar 2021 MEHR MODERNE FÜR DAS LENBACHHAUS ie weltweit größte Sammlung zur Kunst des Blauen Reiter, die das Lenbachhaus sein Eigen nennen darf, verdankt das Museum in erster Linie der großzügigen Stiftung von Gabriele Münter. 1957 machte die einzigartige Schenkung anlässlich des 80. Geburtstags der D Künstlerin die Städtische Galerie zu einem Museum von Weltrang. Das herausragende Geschenk umfasste zahlreiche Werke von Wassily Kandinsky bis 1914, von Münter selbst sowie Arbeiten von Künstlerkolleg*innen aus dem erweiterten Kreis des Blauen Reiter. Es folgten bedeutende Ankäufe und Schen- kungen wie 1965 die ebenfalls außerordentlich großzügige Stiftung von Elly und Bernhard Koehler jun., dem Sohn des wichtigen Mäzens und Sammlers, mit Werken von Franz Marc und August Macke. Damit wurde das Lenbachhaus zum zentralen Ort der Erfor- schung und Vermittlung der Kunst des Blauen Reiter und nimmt diesen Auftrag seit über sechs Jahrzehnten insbesondere mit seiner August Macke Ausstellungstätigkeit wahr. Treibende Kraft Reiter ist keinesfalls abgeschlossen, ganz im KINDER AM BRUNNEN II, hinter dieser Entwicklung war Hans Konrad Gegenteil: Je weniger Leerstellen verbleiben, CHILDREN AT THE FOUNTAIN II Roethel, Direktor des Lenbachhauses von desto schwieriger gestaltet sich die Erwer- 1956 bis 1971. Nach seiner Amtszeit haben bungstätigkeit. In den vergangenen Jahren hat 1910 sich auch Armin Zweite und Helmut Friedel sich das Lenbachhaus bemüht, die Sammlung Öl auf Leinwand / oil on canvas 80,5 x 60 cm erfolgreich für die Erweiterung der Sammlung um diese besonderen, selten aufzufindenden FVL 43 engagiert. -

Exhibit Order Form

40% Exhibit Discount Valid Until April 13, 2021 University of Chicago Press Books are for display only. Order on-site and receive FREE SHIPPING. EX56775 / EX56776 Ship To: Name Address Shipping address on your business card? City, State, Zip Code STAPLE IT HERE Country Email or Telephone (required) Return this form to our on-site representative. OR Mail/fax orders with payment to: Buy online: # of Books: _______ Chicago Distribution Center Visit us at www.press.uchicago.edu. Order Department To order books from this meeting online, 11030 S. Langley Ave go to www.press.uchicago.edu/directmail Subtotal Chicago, IL 60628 and use keycode EX56776 to apply the USA 40% exhibit Fax: 773.702.9756 *Sales Tax Customer Service: 1.800.621.2736 **Shipping and Ebook discount: Most of the books published by the University of Chicago Press are also Handling available in e-book form. Chicago e-books can be bought and downloaded from our website at press.uchicago.edu. To get a 20% discount on e-books published by the University of Chicago Press, use promotional code UCPXEB during checkout. (UCPXEB TOTAL: only applies to full-priced e-books (All prices subject to change) For more information about our journals and to order online, visit *Shipments to: www.journals.uchicago.edu. Illinois add 10.25% Indiana add 7% Massachusets add 6.25% California add applicable local sales tax Washington add applicable local sales tax College Art Association New York add applicable local sales tax Canada add 5% GST (UC Press remits GST to Revenue Canada. Your books will / February 10 - 13, 2021 be shipped from inside Canada and you will not be assessed Canada Post's border handling fee.) Payment Method: Check Credit Card ** If shipping: $6.50 first book Visa MasterCard American Express Discover within U.S.A. -

Alexander Von Salzmann 1874 Tbilisi (Georgia) – 1934 Leysin (Switzerland)

Alexander von Salzmann 1874 Tbilisi (Georgia) – 1934 Leysin (Switzerland) A native of Tbilisi, Alexander von Salzmann was born into a cultivated family and received a thorough upbringing and early training in art, music and drama. Fluent in four languages – Russian, German, English and French – he was often described as sensitive and amiable but at the same time reputed to be unreliable and indolent. He trained as a painter in Moscow, later moving to Munich where he enrolled at the Academy of Fine Arts in 1898 to study under Franz Stuck. Two years later, Wassily Kandinsky joined the same painting class. A large number of Russian artists were living and working in Munich around the turn of the twentieth century. Kandinsky, who had a strong network of contacts within Schwabing’s vibrant art world, introduced Salzmann to one of his many Russian contacts – the painter Alexej von Jawlensky. Jawlensky was romantically involved with Marianne von Werefkin, a Russian aristocrat and painter who had made the decision to interrupt her own artistic Alexander von Salzmann, Self-portrait, career to further Jawlensky’s painting. In her elegant Munich 1905 apartment Werefkin hosted a Salon which grew to be a hub of literary and artistic exchange. Salzmann soon became a regular visitor and before long was making advances to his hostess. Despite a significant age difference, they became lovers but the affair ended abruptly in 1905. Six years later Kandinsky, Jawlensky and Werefkin formed The Blue Rider, one of the leading artists’ groups of the twentieth century. Like many other Munich-based, emerging artists of the period Salzmann earned his living as an illustrator for the magazine Jugend. -

Max Beckmann Alexej Von Jawlensky Ernst Ludwig Kirchner Fernand Léger Emil Nolde Pablo Picasso Chaim Soutine

MMEAISSTTEERRWPIECREKSE V V MAX BECKMANN ALEXEJ VON JAWLENSKY ERNST LUDWIG KIRCHNER FERNAND LÉGER EMIL NOLDE PABLO PICASSO CHAIM SOUTINE GALERIE THOMAS MASTERPIECES V MASTERPIECES V GALERIE THOMAS CONTENTS MAX BECKMANN KLEINE DREHTÜR AUF GELB UND ROSA 1946 SMALL REVOLVING DOOR ON YELLOW AND ROSE 6 STILLEBEN MIT WEINGLÄSERN UND KATZE 1929 STILL LIFE WITH WINE GLASSES AND CAT 16 ALEXEJ VON JAWLENSKY STILLEBEN MIT OBSTSCHALE 1907 STILL LIFE WITH BOWL OF FRUIT 26 ERNST LUDWIG KIRCHNER LUNGERNDE MÄDCHEN 1911 GIRLS LOLLING ABOUT 36 MÄNNERBILDNIS LEON SCHAMES 1922 PORTRAIT OF LEON SCHAMES 48 FERNAND LÉGER LA FERMIÈRE 1953 THE FARMER 58 EMIL NOLDE BLUMENGARTEN G (BLAUE GIEßKANNE) 1915 FLOWER GARDEN G (BLUE WATERING CAN) 68 KINDER SOMMERFREUDE 1924 CHILDREN’S SUMMER JOY 76 PABLO PICASSO TROIS FEMMES À LA FONTAINE 1921 THREE WOMEN AT THE FOUNTAIN 86 CHAIM SOUTINE LANDSCHAFT IN CAGNES ca . 1923-24 LANDSCAPE IN CAGNES 98 KLEINE DREHTÜR AUF GELB UND ROSA 1946 SMALL REVOLVING DOOR ON YELLOW AND ROSE MAX BECKMANN oil on canvas Provenance 1946 Studio of the Artist 60 x 40,5 cm Hanns and Brigitte Swarzenski, New York 5 23 /8 x 16 in. Private collection, USA (by descent in the family) signed and dated lower right Private collection, Germany (since 2006) Göpel 71 2 Exhibited Busch Reisinger Museum, Cambridge/Mass. 1961. 20 th Century Germanic Art from Private Collections in Greater Boston. N. p., n. no. (title: Leaving the restaurant ) Kunsthalle, Mannheim; Hypo Kunsthalle, Munich 2 01 4 - 2 01 4. Otto Dix und Max Beckmann, Mythos Welt. No. 86, ill. p. 156.