66011 301171.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Bank of the European Union (Sabine Tissot) the Authors Do Not Accept Responsibility for the 1958-2008 • 1958-2008 • 1958-2008 Translations

The book is published and printed in Luxembourg by 1958-2008 • 1958-2008 • 1958-2008 1958-2008 • 1958-2008 • 1958-2008 15, rue du Commerce – L-1351 Luxembourg 3 (+352) 48 00 22 -1 5 (+352) 49 59 63 1958-2008 • 1958-2008 • 1958-2008 U [email protected] – www.ic.lu The history of the European Investment Bank cannot would thus mobilise capital to promote the cohesion be dissociated from that of the European project of the European area and modernise the economy. 1958-2008 • 1958-2008 • 1958-2008 The EIB yesterday and today itself or from the stages in its implementation. First These initial objectives have not been abandoned. (cover photographs) broached during the inter-war period, the idea of an 1958-2008 • 1958-2008 • 1958-2008 The Bank’s history symbolised by its institution for the financing of major infrastructure in However, today’s EIB is very different from that which 1958-2008 • 1958-2008 • 1958-2008 successive headquarters’ buildings: Europe resurfaced in 1949 at the time of reconstruction started operating in 1958. The Europe of Six has Mont des Arts in Brussels, and the Marshall Plan, when Maurice Petsche proposed become that of Twenty-Seven; the individual national 1958-2008 • 1958-2008 • 1958-2008 Place de Metz and Boulevard Konrad Adenauer the creation of a European investment bank to the economies have given way to the ‘single market’; there (West and East Buildings) in Luxembourg. Organisation for European Economic Cooperation. has been continuous technological progress, whether 1958-2008 • 1958-2008 • 1958-2008 in industry or financial services; and the concerns of The creation of the Bank was finalised during the European citizens have changed. -

European Integration Theories: the Case of Eec Merger Policy

1 EUROPEAN INTEGRATION THEORIES: THE CASE OF EEC MERGER POLICY Patricia Garcia-Duran Huet London School of Economics and Political Science PhD UMI Number: U615564 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U615564 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 I l+£S^S F IS llo 7 o \ l i n - 2 ABSTRACT Political scientists have been searching for a comprehensive theoretical framework to explain the dynamics of European integration since the European Communities came into being in the early 1950s. European integration theory was dominated by neo-fiinctionalism in the 1960s and by realism in the 1970s and early 1980s. In the late 1980s these two paradigms were finally confronted. As a result of this confrontation, there seems to be an emergence of a new approach based on the idea that neither neo-functionalism nor realism alone can explain European integration but that each perspective provides fundamental insights. Multi-level governance models and even state-centred models tend to recognise that both theoretical frameworks have something to offer. -

REY Commission (1967-1970)

COMPOSITION OF THE COMMISSION 1958-2004 HALLSTEIN Commission (1958-1967) REY Commission (1967-1970) MALFATTI – MANSHOLT Commission (1970-1973) ORTOLI Commission (1973-1977) JENKINS Commission (1977-1981) THORN Commission (1981-1985) DELORS Commission (1985) DELORS Commission (1986-1988) DELORS Commission (1989-1995) SANTER Commission (1995-1999) PRODI Commission (1999-2004) HALLSTEIN COMMISSION 1 January 1958 – 30 June 1967 TITLE RESPONSIBLITIES REPLACEMENT (Date appointed) Walter HALLSTEIN President Administration Sicco L. MANSHOLT Vice-President Agriculture Robert MARJOLIN Vice-President Economics and Finance Piero MALVESTITI Vice-President Internal Market Guiseppe CARON (resigned September 1959) (24 November 1959) (resigned 15 May 1963) Guido COLONNA di PALIANO (30 July 1964) Robert LEMAIGNEN Member Overseas Development Henri ROCHEREAU (resigned January 1962) (10 January 1962) Jean REY Member External Relations Hans von der GROEBEN Member Competition Guiseppe PETRILLI Member Social Affairs Lionello LEVI-SANDRI (resigned September 1960) (8 February 1961) named Vice-president (30 July 1064) Michel RASQUIN (died 27 April 1958) Member Transport Lambert SCHAUS (18 June 1958) REY COMMISSION 2 July 1967 – 1 July 1970 TITLE RESPONSIBLITIES REPLACEMENT (Date appointed) Jean REY President Secretariat General Legal Service Spokesman’s Service Sicco L. MANSHOLT Vice-president Agriculture Lionelle LEVI SANDRI Vice-president Social Affairs Personnel/Administration Fritz HELLWIG Vice-president Research and Technology Distribution of Information Joint -

Wilfried Loth Building Europe

Wilfried Loth Building Europe Wilfried Loth Building Europe A History of European Unification Translated by Robert F. Hogg An electronic version of this book is freely available, thanks to the support of libra- ries working with Knowledge Unlatched. KU is a collaborative initiative designed to make high quality books Open Access. More information about the initiative can be found at www.knowledgeunlatched.org This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 License. For details go to http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. ISBN 978-3-11-042777-6 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-042481-2 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-042488-1 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A CIP catalog record for this book has been applied for at the Library of Congress. Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available in the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. © 2015 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston Cover image rights: ©UE/Christian Lambiotte Typesetting: Michael Peschke, Berlin Printing: CPI books GmbH, Leck ♾ Printed on acid free paper Printed in Germany www.degruyter.com Table of Contents Abbreviations vii Prologue: Churchill’s Congress 1 Four Driving Forces 1 The Struggle for the Congress 8 Negotiations and Decisions 13 A Milestone 18 1 Foundation Years, 1948–1957 20 The Struggle over the Council of Europe 20 The Emergence of the Coal and Steel Community -

Histoire De La Commission Européenne 1958

KA-01-13-684-FR-C HISTOIRE ET MÉMOIRES D’UNE INSTITUTION HISTOIRE LA COMMISSION EUROPÉENNE «Seules les institutions deviennent plus sages: Les traités de Rome du 25 mars 1957 à peine signés, la Commission se mettait en place, Entreprise à la demande de la Commission elles accumulent l’expérience collective [...].» dès le 1er janvier 1958 à Bruxelles, avec un cahier des charges touchant tous les secteurs euro péenne, cette étude est à la fois un tra- Henri-Frédéric Amiel, de la vie économique des six pays fondateurs: l’Allemagne, la France, l’Italie et les trois vail d’histoire et de mémoire. Des historiens cité par Jean Monnet, Mémoires, p. 461. pays du Benelux — la Belgique, le Luxembourg et les Pays-Bas. des six pays fondateurs ont exploité un nom- bre appréciable de fonds d’archives, notamment Les quinze années couvertes par le présent ouvrage, 1958-1972, correspondent communautaires. Ils ont en outre bénéficié de à la période fondatrice de la Commission européenne, dont la mission première consistera 120 témoignages d’anciens fonctionnaires, qui «La Commission devait avoir le courage de dé- à proposer des mesures concrètes pour réaliser l’objectif principal du traité — la création sont autant d’acteurs et de témoins de ce que cider. Ce n’est qu’en ayant la volonté et la ca- d’un marché commun —, en prenant désormais comme critère d’action l’intérêt général l’un d’entre eux a nommé «une invention de pacité de prendre toutes les décisions que l’on de l’ensemble de la Communauté des six pays membres. -

Eu Whoiswho Annuaire Officiel De L'union Européenne Commission Européenne 16/12/2017

UNION EUROPÉENNE EU WHOISWHO ANNUAIRE OFFICIEL DE L'UNION EUROPÉENNE COMMISSION EUROPÉENNE 16/12/2017 Géré par l'Office des publications © Union européenne, 2017 FOP engine ver:20171120 - Content: - merge of files"temp/CRF_COM_Commission_prod_dontimport.RNS.FX.TRAD.DPO.dated.XML1.5.postCRF.ANN.xml", "The_College.xml", "temp/CRF_COM_CABINETS.RNS.FX.TRAD.DPO.dated.XML1.5.postCRF.ANN.xml", "temp/ CRF_COM_SG.RNS.FX.TRAD.DPO.dated.XML1.5.postCRF.ANN.xml", "temp/CRF_COM_SJ.RNS.FX.TRAD.DPO.dated.XML1.5.postCRF.ANN.xml", "temp/CRF_COM_COMMU.RNS.FX.TRAD.DPO.dated.XML1.5.postCRF.ANN.xml", "temp/CRF_COM_EPSC.RNS.FX.TRAD.DPO.dated.XML1.5.postCRF.ANN.xml", "temp/CRF_COM_TASKF_A50_UK.RNS.FX.TRAD.DPO.dated.XML1.5.postCRF.ANN.xml", "temp/CRF_COM_ECFIN.RNS.FX.TRAD.DPO.dated.XML1.5.postCRF.ANN.xml", "temp/CRF_COM_GROW.RNS.FX.TRAD.DPO.dated.XML1.5.postCRF.ANN.xml", "temp/ CRF_COM_COMP.RNS.FX.TRAD.DPO.dated.XML1.5.postCRF.ANN.xml", "temp/CRF_COM_EMPL.RNS.FX.TRAD.DPO.dated.XML1.5.postCRF.ANN.xml", "temp/CRF_COM_AGRI.RNS.FX.TRAD.DPO.dated.XML1.5.postCRF.ANN.xml", "temp/CRF_COM_ENER.RNS.FX.TRAD.DPO.dated.XML1.5.postCRF.ANN.xml", "temp/CRF_COM_CLIMA.RNS.FX.TRAD.DPO.dated.XML1.5.postCRF.ANN.xml", "temp/CRF_COM_MOVE.RNS.FX.TRAD.DPO.dated.XML1.5.postCRF.ANN.xml", "temp/CRF_COM_ENV.RNS.FX.TRAD.DPO.dated.XML1.5.postCRF.ANN.xml", "temp/ CRF_COM_RTD.RNS.FX.TRAD.DPO.dated.XML1.5.postCRF.ANN.xml", "temp/CRF_COM_JRC.RNS.FX.TRAD.DPO.dated.XML1.5.postCRF.ANN.xml", "temp/CRF_COM_CNECT.RNS.FX.TRAD.DPO.dated.XML1.5.postCRF.ANN.xml", "temp/CRF_COM_MARE.RNS.FX.TRAD.DPO.dated.XML1.5.postCRF.ANN.xml", -

EUI Working Papers

ROBERT SCHUMAN CENTRE FOR ADVANCED STUDIES EUI Working Papers RSCAS 2010/80 ROBERT SCHUMAN CENTRE FOR ADVANCED STUDIES THE RISE OF EUROPEAN COMPETITION POLICY, 1950-1991: A CROSS-DISCIPLINARY SURVEY OF A CONTESTED POLICY SPHERE Laurent Warlouzet EUROPEAN UNIVERSITY INSTITUTE, FLORENCE ROBERT SCHUMAN CENTRE FOR ADVANCED STUDIES The Rise of European Competition Policy, 1950-1991: A Cross-Disciplinary Survey of a Contested Policy Sphere LAURENT WARLOUZET EUI Working Paper RSCAS 2010/80 This text may be downloaded only for personal research purposes. Additional reproduction for other purposes, whether in hard copies or electronically, requires the consent of the author(s), editor(s). If cited or quoted, reference should be made to the full name of the author(s), editor(s), the title, the working paper, or other series, the year and the publisher. ISSN 1028-3625 © 2010 Laurent Warlouzet Printed in Italy, October 2010 European University Institute Badia Fiesolana I – 50014 San Domenico di Fiesole (FI) Italy www.eui.eu/RSCAS/Publications/ www.eui.eu cadmus.eui.eu Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies The Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies (RSCAS), directed by Stefano Bartolini since September 2006, is home to a large post-doctoral programme. Created in 1992, it aims to develop inter-disciplinary and comparative research and to promote work on the major issues facing the process of integration and European society. The Centre hosts major research programmes and projects, and a range of working groups and ad hoc initiatives. The research agenda is organised around a set of core themes and is continuously evolving, reflecting the changing agenda of European integration and the expanding membership of the European Union. -

The International Dimension of EU Competition Policy

The International Dimension of EU Competition Policy: Does Regional Supranational Regulation Hinder Protectionism? Hikaru YOSHIZAWA Thèse présentée en vue de l'obtention du grade académique de Docteur en Sciences Politiques et sociales sous la codirection de Madame la Professeure Janine GOETSCHY (ULB & CNRS) et Monsieur le Professeur René SCHWOK (UNIGE) Année académique 2015-2016 1 Abstract There is an increasing recognition of the international presence and regulatory influence of the EU in competition policy. Despite a scholarly focus on its international dimension, the issue of nationality-based (non-) discrimination has insufficiently been investigated in the existing literature on EU competition policy. Thus, this research aims to fill this gap in the literature by examining whether the EU internally and externally utilizes its competition rules for the objective of promoting (potential) national and European champions, while disadvantaging non-EU based companies operating inside and outside the European internal market. Empirical findings validate two hypotheses of this research: that the supranational institutional setting of the EU in competition policy constrains the ability of member states to use their competition policies for neomercantilist, and even for protectionist purposes; and that the institutional setup assures nationality-blind enforcement by EU competition regulators, even vis-à-vis non-EU based companies. The research also identifies key systemic factors which either constrain or empower the EU as a regulatory power in the competition policy domain. The empirical analysis draws on both quantitative data and in-depth studies of recent major cases. Most cases are from the period between September 1990 and August 2015, involving American and Japanese companies, which have a strong presence in European economies. -

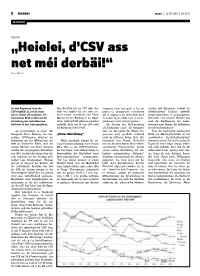

„Heielei, D'csv Ass Net Méi Derbäi!“

8 REGARDS woxx | 26 07 2013 | Nr 1225 GESCHICHT POLITIK „Heielei, d’CSV ass net méi derbäi!“ Renée Wagener Ist eine Regierung ohne die Eine Koalition mit der CSV wäre also s’imposer dans leur parti et lui im- sierung und Expansion, sowohl die CSV möglich? Ja, es hat sogar nicht viel stabiler als eine ohne sie. primer ce changement d‘orientation Gewährleistung höchster Entwick- schon einmal eine gegeben. Ein Recht schnell entscheidet sich Pierre qui le déplacera du centre-droit où il lungsmöglichkeiten in pädagogischer, historischer Blick zurück auf die Werner für den Rückzug in die Oppo- se trouve depuis 1945, vers le centre- kultureller und sozialer Hinsicht wie Entstehung der sozialliberalen sition. LSAP und DP scheinen zunächst gauche où il était avant la guerre.“ auch die Eindämmung des Luxus- Koalition in den Siebzigerjahren. verblüfft, doch am 15. Juni 1974 steht Der Einsatz der Wochenzeitung Konsums zum Nutzen der kollektiven die Regierung Thorn-Vouel. „d‘Lëtzebuerger Land“ als Königsma- Investitionsbedürfnisse“. „Le gouvernement se retire.“ Der cher, auf den später des Öfteren hin- Dass die marxistisch angehauchte Ausspruch Pierre Werners, des ehe- „Echter Gleichklang“ gewiesen wird, geschieht demnach Kritik des Aktionsprogramms an der maligen CSV-Premiers, während der nicht im luftleeren Raum. Ende 1972 „neoliberalen Gesellschaftsordnung“ Diskussion um den Militärdienst, die Völlig unverhofft kommt die rot- konstatiert Léon Kinsch, Chefredak- zumindest einem Teil der Liberalen im 1966 zur Staatskrise führte, wird seit blaue Koalition allerdings nicht. Bereits teur des liberalen Blattes, Marcel Marts Folgenden keine Angst einjagt, erklärt einigen Wochen viel zitiert. Genauso Mitte 1972, so der LSAP-Parteihistori- „neoliberaler Progressismus“ besitze sich auch dadurch, dass sich die DP werden die vorgezogenen Neuwahlen ker Ben Fayot, hatte Robert Krieps in „einen echten Gleichklang mit We- selbst unter ihrem „coming man“ Gas- von 1968, bis dato die letzten ihrer Art, Presseartikeln die Möglichkeit einer henkels reformistischer Reflexion“. -

Le Luxembourg Face Aux Traités De Rome

Gilbert TRAUSCH Le Luxembourg face aux traités de Rome. La stratégie d'un petit pays publié IN: Centre d'études et de recherches européennes Robert Schuman (Collectif), Le Luxembourg face à la construction européenne – Luxemburg und die europäische Einigung, Luxembourg, 1996, pp.119-146 Il nous paraît utile de commencer par deux citations de Joseph Bech, l'inamovible Ministre luxembourgeois des Affaires étrangères – il était en poste de 1926 à 1959 sans interruption.1 Elles illustrent l'intérêt exceptionnel qu'une union européenne présente pour le Luxembourg et les graves risques que celle-ci comporte pour un pays aussi petit. Dès 1942, parti en exil avec le gouvernement luxembourgeois, J. Bech exprime devant la Commission des Affaires étrangères de la Chambre des Représentants à Washington sa vision de l'Europe d'après-guerre. Déjà il a bien compris les deux nécessités essentielles de la nouvelle Europe: commencer l'œuvre d'unification par le terrain le plus facile en créant un marché économique européen mais prendre bien soin d'y inclure l'Allemagne, si possible une Allemagne ramenée à des proportions plus acceptables: «In my view Europe is ready to unite - at least economically […]. But there is another fact which cannot but have an influence on the co-operation of the European nations. There is Germany and Germany cannot be excluded from the European Community. Even disarmed, and if possible spilt up …».2 Bech aime citer un proverbe français pour attirer l'attention sur les problèmes que l'unification européenne pose aux petits pays: «Tandis qu'un gros devient maigre, un maigre passe de vie à trépas». -

CERE) a Son Siège Dans La Maison Natale De Robert Schuman, Ancien Ministre Français Des Affaires Étrangères Et Père Fondateur De L'europe

Centre d'études et de recherches européennes Robert Schuman Rapport d’activités pour l'année 2012 Le Centre d'études et de recherches européennes (CERE) a son siège dans la maison natale de Robert Schuman, ancien ministre français des Affaires étrangères et père fondateur de l'Europe. Travaux d'extension du CERE La rénovation de l'ancien presbytère de Clausen va bon train. Les travaux de gros-œuvres ont commencé après le congé collectif en septembre. Ils sont actuellement achevés. Entre-temps aussi les anciennes fenêtres ont été arrachées et remplacées et la toiture a été refaite, de sorte que les électriciens, les monteurs du chauffage et les installateurs du sanitaire pourront démarrer leurs travaux en janvier 2013, comme prévu par le calendrier de l'architecte. Sauf imprévu, la rénovation sera donc achevée dans le courant de la seconde moitié de 2013. Colloques, conférences, rencontres et séances d'information Les collaborateurs du CERE ont organisé/participé/assisté à de nombreux colloques scientifiques, conférences, rencontres internationales, dont nous n'aimerions citer que quelques exemples: - série de conférences organisées au Portugal par S.Exc. Monsieur l'Ambassadeur Paul Schmit dans le cadre de la présentation du manuel d'histoire História do Luxemburgo par le professeur Gilbert Trausch; - colloque à Louvain-la-Neuve en vue de préparer la rédaction de l'Histoire de la Commission européenne entre 1973 et 1986 (tome deuxième); - pre-Presidency Conference du réseau TEPSA à Nicosie (14-15 juin 2012): Préparation de la présidence -

The More Economic Approach to EU Antitrust Law

The More Economic Approach to EU Antitrust Law Anne C Witt OXFORD AND PORTLAND, OREGON 2016 Hart Publishing An imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc Hart Publishing Ltd Bloomsbury Publishing Plc Kemp House 50 Bedford Square Chawley Park London Cumnor Hill WC1B 3DP Oxford OX2 9PH UK UK www.hartpub.co.uk www.bloomsbury.com Published in North America (US and Canada) by Hart Publishing c/o International Specialized Book Services 920 NE 58th Avenue, Suite 300 Portland , OR 97213-3786 USA www.isbs.com HART PUBLISHING, the Hart/Stag logo, BLOOMSBURY and the Diana logo are trademarks of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc First published 2016 © Anne C Witt Anne C Witt has asserted her right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 to be identifi ed as Author of this work. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publishers. While every care has been taken to ensure the accuracy of this work, no responsibility for loss or damage occasioned to any person acting or refraining from action as a result of any statement in it can be accepted by the authors, editors or publishers. All UK Government legislation and other public sector information used in the work is Crown Copyright © . All House of Lords and House of Commons information used in the work is Parliamentary Copyright © . This information is reused under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0 ( http://www.nationalarchives.