An Analysis of Miguel Cabrera's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

University of Southern Denmark

UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHERN DENMARK THE CHRISTIAN KINGDOM AS AN IMAGE OF THE HEAVENLY KINGDOM ACCORDING TO ST. BIRGITTA OF SWEDEN A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF HUMANITIES IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY INSTITUTE OF HISTORY, CULTURE AND CIVILISATION CENTRE FOR MEDIEVAL STUDIES BY EMILIA ŻOCHOWSKA ODENSE FEBRUARY 2010 2 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS In my work, I had the privilege to be guided by three distinguished scholars: Professor Jacek Salij in Warsaw, and Professors Tore Nyberg and Kurt Villads Jensen in Odense. It is a pleasure to admit that this study would never been completed without the generous instruction and guidance of my masters. Professor Salij introduced me to the world of ancient and medieval theology and taught me the rules of scholarly work. Finally, he encouraged me to search for a new research environment where I could develop my skills. I found this environment in Odense, where Professor Nyberg kindly accepted me as his student and shared his vast knowledge with me. Studying with Professor Nyberg has been a great intellectual adventure and a pleasure. Moreover, I never would have been able to work at the University of Southern Denmark if not for my main supervisor, Kurt Villads Jensen, who trusted me and decided to give me the opportunity to study under his kind tutorial, for which I am exceedingly grateful. The trust and inspiration I received from him encouraged me to work and in fact made this study possible. Karen Fogh Rasmussen, the secretary of the Centre of Medieval Studies, had been the good spirit behind my work. -

Historical Origins of the One-Drop Racial Rule in the United States

Historical Origins of the One-Drop Racial Rule in the United States Winthrop D. Jordan1 Edited by Paul Spickard2 Editor’s Note Winthrop Jordan was one of the most honored US historians of the second half of the twentieth century. His subjects were race, gender, sex, slavery, and religion, and he wrote almost exclusively about the early centuries of American history. One of his first published articles, “American Chiaroscuro: The Status and Definition of Mulattoes in the British Colonies” (1962), may be considered an intellectual forerunner of multiracial studies, as it described the high degree of social and sexual mixing that occurred in the early centuries between Africans and Europeans in what later became the United States, and hinted at the subtle racial positionings of mixed people in those years.3 Jordan’s first book, White over Black: American Attitudes Toward the Negro, 1550–1812, was published in 1968 at the height of the Civil Rights Movement era. The product of years of painstaking archival research, attentive to the nuances of the thousands of documents that are its sources, and written in sparkling prose, White over Black showed as no previous book had done the subtle psycho-social origins of the American racial caste system.4 It won the National Book Award, the Ralph Waldo Emerson Prize, the Bancroft Prize, the Parkman Prize, and other honors. It has never been out of print since, and it remains a staple of the graduate school curriculum for American historians and scholars of ethnic studies. In 2005, the eminent public intellectual Gerald Early, at the request of the African American magazine American Legacy, listed what he believed to be the ten most influential books on African American history. -

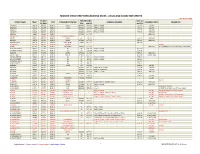

Residential Resurfacing List

MISSION VIEJO STREET RESURFACING INDEX - LOCAL AND COLLECTOR STREETS Rev. DEC 31, 2020 TB MAP RESURFACING LAST AC STREET NAME TRACT TYPE COMMUNITY/OWNER ADDRESS NUMBERS PAVEMENT INFO COMMENTS PG GRID TYPE MO/YR MO/YR ABADEJO 09019 892 E7 PUBLIC OVGA RPMSS1 OCT 18 28241 to 27881 JUL 04 .4AC/NS ABADEJO 09018 892 E7 PUBLIC OVGA RPMSS1 OCT 18 27762 to 27832 JUL 04 .4AC/NS ABANICO 09566 892 D2 PUBLIC RPMSS OCT 17 27551 to 27581 SEP 10 .35AC/NS ABANICO 09568 892 D2 PUBLIC RPMSS OCT 17 27541 to 27421 SEP 10 .35AC/NS ABEDUL 09563 892 D2 PUBLIC RPMSS OCT 17 .35AC/NS ABERDEEN 12395 922 C7 PRIVATE HIGHLAND CONDOS -- ABETO 08732 892 D5 PUBLIC MVEA AC JUL 15 JUL 15 .35AC/NS ABRAZO 09576 892 D3 PUBLIC MVEA RPMSS OCT 17 SEP 10 .35AC/NS ACACIA COURT 08570 891 J6 PUBLIC TIMBERLINE TRMSS OCT 14 AUG 08 ACAPULCO 12630 892 F1 PRIVATE PALMIA -- GATED ACERO 79-142 892 A6 PUBLIC HIGHPARK TRMSS OCT 14 .55AC/NS 4/1/17 TRMSS 40' S of MAQUINA to ALAMBRE ACROPOLIS DRIVE 06667 922 A1 PUBLIC AH AC AUG 08 24582 to 24781 AUG 08 ACROPOLIS DRIVE 07675 922 A1 PUBLIC AH AC AUG 08 24801 to 24861 AUG 08 ADELITA 09078 892 D4 PUBLIC MVEA RPMSS OCT 17 SEP 10 .35AC/NS ADOBE LANE 06325 922 C1 PUBLIC MVSRC RPMSS OCT 17 AUG 08 .17SAC/.58AB ADONIS STREET 06093 891 J7 PUBLIC AH AC SEP 14 24161 to 24232 SEP 14 ADONIS STREET 06092 891 J7 PUBLIC AH AC SEP 14 24101 to 24152 SEP 14 ADRIANA STREET 06092 891 J7 PUBLIC AH AC SEP 14 SEP 14 AEGEA STREET 06093 891 J7 PUBLIC AH AC SEP 14 SEP 14 AGRADO 09025 922 D1 PUBLIC OVGA AC AUG 18 AUG 18 .4AC/NS AGUILAR 09255 892 D1 PUBLIC RPMSS OCT 17 PINAVETE -

Information to Users

Eighteenth century caste paintings: The implications of Miguel Cabrera's series Item Type text; Thesis-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Arana, Emilia Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 01/10/2021 21:40:45 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/278537 INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerograpnically in this copy. -

DOWNLOAD Primerang Bituin

A publication of the University of San Francisco Center for the Pacific Rim Copyright 2006 Volume VI · Number 1 15 May · 2006 Special Issue: PHILIPPINE STUDIES AND THE CENTENNIAL OF THE DIASPORA Editors Joaquin Gonzalez John Nelson Philippine Studies and the Centennial of the Diaspora: An Introduction Graduate Student >>......Joaquin L. Gonzalez III and Evelyn I. Rodriguez 1 Editor Patricia Moras Primerang Bituin: Philippines-Mexico Relations at the Dawn of the Pacific Rim Century >>........................................................Evelyn I. Rodriguez 4 Editorial Consultants Barbara K. Bundy Hartmut Fischer Mail-Order Brides: A Closer Look at U.S. & Philippine Relations Patrick L. Hatcher >>..................................................Marie Lorraine Mallare 13 Richard J. Kozicki Stephen Uhalley, Jr. Apathy to Activism through Filipino American Churches Xiaoxin Wu >>....Claudine del Rosario and Joaquin L. Gonzalez III 21 Editorial Board Yoko Arisaka The Quest for Power: The Military in Philippine Politics, 1965-2002 Bih-hsya Hsieh >>........................................................Erwin S. Fernandez 38 Uldis Kruze Man-lui Lau Mark Mir Corporate-Community Engagement in Upland Cebu City, Philippines Noriko Nagata >>........................................................Francisco A. Magno 48 Stephen Roddy Kyoko Suda Worlds in Collision Bruce Wydick >>...................................Carlos Villa and Andrew Venell 56 Poems from Diaspora >>..................................................................Rofel G. Brion -

The Art of Conversation: Eighteenth-Century Mexican Casta Painting

Graduate Journal of Visual and Material Culture Issue 5 I 2012 The Art of Conversation: Eighteenth-Century Mexican Casta Painting Mey-Yen Moriuchi ______________________________________________ Abstract: Traditionally, casta paintings have been interpreted as an isolated colonial Mexican art form and examined within the social historical moment in which they emerged. Casta paintings visually represented the miscegenation of the Spanish, Indian and Black African populations that constituted the new world and embraced a diverse terminology to demarcate the land’s mixed races. Racial mixing challenged established social and racial categories, and casta paintings sought to stabilize issues of race, gender and social status that were present in colonial Mexico. Concurrently, halfway across the world, another country’s artists were striving to find the visual vocabulary to represent its families, socio-economic class and genealogical lineage. I am referring to England and its eighteenth-century conversation pictures. Like casta paintings, English conversation pieces articulate beliefs about social and familial propriety. It is through the family unit and the presence of a child that a genealogical statement is made and an effigy is preserved for subsequent generations. Utilizing both invention and mimesis, artists of both genres emphasize costume and accessories in order to cater to particular stereotypes. I read casta paintings as conversations like their European counterparts—both internal conversations among the figures within the frame, and external ones between the figures, the artist and the beholder. It is my position that both casta paintings and conversation pieces demonstrate a similar concern with the construction of a particular self-image in the midst of societies that were apprehensive about the varying conflicting notions of socio-familial and socio-racial categories. -

1 LAH 6934: Colonial Spanish America Ida Altman T 8-10

LAH 6934: Colonial Spanish America Ida Altman T 8-10 (3-6 p.m.), Keene-Flint 13 Office: Grinter Rm. 339 Email: [email protected] Hours: Th 10-12 The objective of the seminar is to become familiar with trends and topics in the history and historiography of early Spanish America. The field has grown rapidly in recent years, and earlier pioneering work has not been superseded. Our approach will take into account the development of the scholarship and changing emphases in topics, sources and methodology. For each session there are readings for discussion, listed under the weekly topic. These are mostly journal articles or book chapters. You will write short (2-3 pages) response papers on assigned readings as well as introducing them and suggesting questions for discussion. For each week’s topic a number of books are listed. You should become familiar with most of this literature if colonial Spanish America is a field for your qualifying exams. Each student will write two book reviews during the semester, to be chosen from among the books on the syllabus (or you may suggest one). The final paper (12-15 pages in length) is due on the last day of class. If you write a historiographical paper it should focus on the most important work on the topic rather than being bibliographic. You are encouraged to read in Spanish as well as English. For a fairly recent example of a historiographical essay, see R. Douglas Cope, “Indigenous Agency in Colonial Spanish America,” Latin American Research Review 45:1 (2010). You also may write a research paper. -

![Genetic Divergence and Polyphyly in the Octocoral Genus Swiftia [Cnidaria: Octocorallia], Including a Species Impacted by the DWH Oil Spill](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9917/genetic-divergence-and-polyphyly-in-the-octocoral-genus-swiftia-cnidaria-octocorallia-including-a-species-impacted-by-the-dwh-oil-spill-739917.webp)

Genetic Divergence and Polyphyly in the Octocoral Genus Swiftia [Cnidaria: Octocorallia], Including a Species Impacted by the DWH Oil Spill

diversity Article Genetic Divergence and Polyphyly in the Octocoral Genus Swiftia [Cnidaria: Octocorallia], Including a Species Impacted by the DWH Oil Spill Janessy Frometa 1,2,* , Peter J. Etnoyer 2, Andrea M. Quattrini 3, Santiago Herrera 4 and Thomas W. Greig 2 1 CSS Dynamac, Inc., 10301 Democracy Lane, Suite 300, Fairfax, VA 22030, USA 2 Hollings Marine Laboratory, NOAA National Centers for Coastal Ocean Sciences, National Ocean Service, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, 331 Fort Johnson Rd, Charleston, SC 29412, USA; [email protected] (P.J.E.); [email protected] (T.W.G.) 3 Department of Invertebrate Zoology, National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, 10th and Constitution Ave NW, Washington, DC 20560, USA; [email protected] 4 Department of Biological Sciences, Lehigh University, 111 Research Dr, Bethlehem, PA 18015, USA; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Mesophotic coral ecosystems (MCEs) are recognized around the world as diverse and ecologically important habitats. In the northern Gulf of Mexico (GoMx), MCEs are rocky reefs with abundant black corals and octocorals, including the species Swiftia exserta. Surveys following the Deepwater Horizon (DWH) oil spill in 2010 revealed significant injury to these and other species, the restoration of which requires an in-depth understanding of the biology, ecology, and genetic diversity of each species. To support a larger population connectivity study of impacted octocorals in the Citation: Frometa, J.; Etnoyer, P.J.; GoMx, this study combined sequences of mtMutS and nuclear 28S rDNA to confirm the identity Quattrini, A.M.; Herrera, S.; Greig, Swiftia T.W. -

IGNACIO MARTÍNEZ (December 2020)

IGNACIO MARTÍNEZ (December 2020) The University of Texas at El Paso [email protected] Department of History Office: (915) 747-7054 Liberal Arts, 320 Liberal Arts 316 El Paso, TX 79968 ACADEMIC APPOINTMENTS Ph.D. Program Director and Associate Chair, University of Texas at El Paso, 2019 - Associate Professor of Colonial Latin America, University of Texas at El Paso, 2019 - Assistant Professor of Colonial Latin America, University of Texas at El Paso, 2013-2019 Assistant Professor of Latin American History, Arkansas State University, 2012-2013 EDUCATION Ph.D. in History, University of Arizona, 2013 M.A. in Latin American Studies, University of New Mexico, 2006 (Defended with honors) Gonville and Caius, University of Cambridge, 2004 B.A. in Independent Studies, University of New Mexico, 2003 A.A. Eastern New Mexico University, 1998 SCHOLARSHIP BOOKS The Intimate Frontier: Friendship and Civil Society in Northern New Spain (Tucson: The University of Arizona Press, 2019). PEER REVIEWED ARTICLES AND BOOK CHAPTERS “The Paradox of Friendship: Loyalty and Betrayal on the Sonoran Frontier,” Journal of the Southwest 56, no. 2 (2014): 319-344. “Settler Colonialism in New Spain and the Early Mexican Republic,” in Ed Cavanagh and Lorenzo Veracini, eds., The Routledge Handbook of the History of Settler Colonialism (Routledge, 2017): 109-124. 1 EDITED WORKS Introduced with Michael Brescia, Tracey Duval, ed., The Marqués de Rubí’s Formidable Inspection Tour of New Spain’s Northern Frontier, 1766-1768, DSWR: Documentary Relations of the Southwest (Under review). Contributing editor with Dale Brenaman, et al., O’odham Pee Posh Documentary History Project, (tentative title) DSWR: Documentary Relations of the Southwest (Forthcoming). -

©2018 Travis Jeffres ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

©2018 Travis Jeffres ALL RIGHTS RESERVED “WE MEXICAS WENT EVERYWHERE IN THAT LAND”: THE MEXICAN INDIAN DIASPORA IN THE GREATER SOUTHWEST, 1540-1680 By TRAVIS JEFFRES A dissertation submitted to the School of Graduate Studies Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Program in History Written under the direction of Camilla ToWnsend And approVed by _____________________________________ _____________________________________ _____________________________________ _____________________________________ New Brunswick, New Jersey October, 2018 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION “We Mexicas Went Everywhere in That Land:” The Mexican Indian Diaspora in the Greater Southwest, 1540-1680 by TRAVIS JEFFRES Dissertation Director: Camilla ToWnsend Beginning With Hernando Cortés’s capture of Aztec Tenochtitlan in 1521, legions of “Indian conquistadors” from Mexico joined Spanish military campaigns throughout Mesoamerica in the sixteenth century. Scholarship appearing in the last decade has revealed the aWesome scope of this participation—involving hundreds of thousands of Indian allies—and cast critical light on their motiVations and experiences. NeVertheless this Work has remained restricted to central Mexico and areas south, while the region known as the Greater SouthWest, encompassing northern Mexico and the U.S. Southwest, has been largely ignored. This dissertation traces the moVements of Indians from central Mexico, especially Nahuas, into this region during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries and charts their experiences as diasporic peoples under colonialism using sources they Wrote in their oWn language (Nahuatl). Their activities as laborers, soldiers, settlers, and agents of acculturation largely enabled colonial expansion in the region. However their exploits are too frequently cast as contributions to an overarching Spanish colonial project. -

Florida's Hispanic Heritage

th 500 Commemoration FLORIDA’S HISPANIC HERITAGE October 13 - 20, 2012 ISLAC (Institute for the Study of Latin America and the Caribbean) at the University of South Florida has organized an international conference and weeklong series of community-oriented events to commemorate Florida’s Hispanic Heritage in honor of the 500th Anniversary of Ponce de Leon’s historic encounter. Welcome On behalf of the Institute for the Study of Latin America and the Caribbean, I would like to welcome you to our commemoration of Florida’s unique and profound Hispanic heritage. In honor of Florida’s own Quincentenary, we are especially privileged to bring together the world’s leading scholars of Florida’s Hispanic past and present. With the support of the Florida Humanities Council, the Tampa Bay History Center and the historic Centro Asturiano, we expect that this conference will help set the stage for what promises to be a memorable Quincentennial year. Warm regards, Essay and Poster Contest Student winners of the 2012 Hispanic Heritage Inc’s essay and poster contests will be recognized at the opening and keynote address. Event Hosts The Institute for the Study of Latin America and the Caribbean at USF is a multidisciplinary area studies center located within the College of Arts and Sciences and USF World. In addition to providing public programming for the USF and Tampa Bay communities, ISLAC provides interdisciplinary and hemispheric perspectives for the study of the region and opportunities for scholarly collaboration for faculty and students in the many different units and departments the Institute integrates. The Florida Humanities Council - an independent, nonprofi t affi liate of the National Endowment for the Humanities - develops and funds public humanities programs and resources statewide. -

LAH 5934: the Iberian Atlantic World Ida Altman T 8-10 (3-6 P.M.), Keene-Flint 13 Grinter 339 Office Hours: M 10:30-12; T, W 2-2:45 [email protected]

LAH 5934: The Iberian Atlantic World Ida Altman T 8-10 (3-6 p.m.), Keene-Flint 13 Grinter 339 Office hours: M 10:30-12; T, W 2-2:45 [email protected] The seminar addresses the early modern Iberian Atlantic world to around 1750, a milieu shaped by European expansion and the complex interactions among peoples and environments that resulted. Main emphasis in the readings is on recent scholarship. Assignments and grades. Students will submit short response papers (2-3 pages, double spaced) on the weekly readings, report on the readings, and suggest questions for discussion. The final paper (around 15-20 pages in length) will consist of either a historiographical essay or a research paper (or some part of one) related to the Iberian Atlantic. Consult me regarding your choice of topic by the end of September. Grades will be based on papers (two-thirds) and class participation, including presentations (one- third). Any unexcused absence will count against the final grade. Reading. The following books are required. Additional readings are available online (journal articles and e-books) and as pdf’s. You may wish to order J.H. Elliott, The Old World and the New (used copies are cheap). For general background reading I recommend James Lockhart and Stuart Schwartz, Early Latin America. Felipe Fernández Armesto, Before Columbus Stuart B. Schwartz, ed., Implicit Understandings Alida C. Metcalf, Go-betweens and the Colonization of Brazil, 1500-1600 Pablo E. Pérez Mallaina, Spain’s Men of the Sea Richard L. Kagan and Philip D. Morgan, eds., Atlantic Diasporas: Jews, Conversos and Crypto-Jews in the Age of Mercantilism, 1500-1800 Stuart B.