Interview with Peter Carey

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reflections on Some Recent Australian Novels ELIZABETH WEBBY

Books and Covers: Reflections on Some Recent Australian Novels ELIZABETH WEBBY For the 2002 Miles Franklin Award, given to the best Australian novel of the year, my fellow judges and I ended up with a short list of five novels. Three happened to come from the same publishing house – Pan Macmillan Australia – and we could not help remarking that much more time and money had been spent on the production of two of the titles than on the third. These two, by leading writers Tim Winton and Richard Flanagan, were hardbacks with full colour dust jackets and superior paper stock. Flanagan’s Gould’s Book of Fish (2001) also featured colour illustrations of the fish painted by Tasmanian convict artist W. B. Gould, the initial inspiration for the novel, at the beginning of each chapter, as well as changes in type colour to reflect the notion that Gould was writing his manuscript in whatever he could find to use as ink. The third book, Joan London’s Gilgamesh (2001), was a first novel, though by an author who had already published two prize- winning collections of short stories. It, however, was published in paperback, with a monochrome and far from eye-catching photographic cover that revealed little about the work’s content. One of the other judges – the former leading Australian publisher Hilary McPhee – was later quoted in a newspaper article on the Award, reflecting on what she described as the “under publishing” of many recent Australian novels. This in turn drew a response from the publisher of another of the short- listed novels, horrified that our reading of the novels submitted for the Miles Franklin Award might have been influenced in any way by a book’s production values. -

An Analysis of Racial Discrimination Potrayed in Peter Carey's Novel

AN ANALYSIS OF RACIAL DISCRIMINATION POTRAYED IN PETER CAREY’S NOVEL : A LONG WAY FROM HOME A THESIS BY ANNISA FITRI REG.NO 160721002 DEPARTEMENT OF ENGLISH FACULTY OF CULTURAL STUDIES UNIVERSITY OF SUMATERA UTARA MEDAN2019 UNIVERSITAS SUMATERA UTARA AN ANALYSIS OF RACIAL DISCRIMINATION POTRAYED IN PETER CAREY’S NOVEL : A LONG WAY FROM HOME A THESIS BY ANNISA FITRI REG. NO. 160721002 SUPERVISOR CO-SUPERVISOR Dr.Siti Norma Nasution, M.Hum Dra. Diah Rahayu Pratma, M.Pd NIP. 195707201983032001 NIP. 195612141986012001 Submitted to Faculty of Cultural Studies University of Sumatera Utara Medan in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Sarjana Sastra From Department of English. DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH FACULTY OF CULTURAL STUDIES UNIVERSITY OF SUMATERA UTARA MEDAN 2019 UNIVERSITAS SUMATERA UTARA Accepted by the Board of Examiners in partial fulfillment of requirements for the degree of SarjanaSastra from the Department of English, Faculty of Cultural Studies University of Sumatera Utara. The examination is held in Department of English Faculty of Cultural Studies University of Sumatera Utara on. Dean of Faculty of Cultural Studies University of Sumatera Utara Dr. Budi Agustono, M.S. NIP. 19600805 198703 1 001 Board of Examiners Dr.Siti Norma Nasution, M.Hum ____________________ Rahmadsyah Rangkuti,MA.,Ph.D. ____________________ Dra. Hj. Swesana Mardia Lubis, M.Hum ____________________ UNIVERSITAS SUMATERA UTARA Approved by the Department of English, Faculty of Cultural Studies, University of Sumatera Utara (USU) Medan as thesis for The Sarjana Sastra Examination. Head, Secretary, Prof. T. SilvanaSinar, M.A., Ph.D. Rahmadsyah Rangkuti, M.A., Ph.D. NIP. 195409161980032003 NIP. 197502092008121002 UNIVERSITAS SUMATERA UTARA AUTHOR’S DECLARATION I,ANNISA FITRI, DECLARE THAT I AM THE SOLE AUTHOR OF THIS THESIS EXCEPT WHERE REFERENCE IS MADE IN THE TEXT OF THIS THESIS. -

Ghosts of Ned Kelly: Peter Carey’S True History and the Myths That Haunt Us

Ghosts of Ned Kelly: Peter Carey’s True History and the myths that haunt us Marija Pericic Master of Arts School of Communication and Cultural Studies Faculty of Arts The University of Melbourne November 2011 Submitted in total fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Master of Arts (by Thesis Only). Abstract Ned Kelly has been an emblem of Australian national identity for over 130 years. This thesis examines Peter Carey’s reimagination of the Kelly myth in True History of the Kelly Gang (2000). It considers our continued investment in Ned Kelly and what our interpretations of him reveal about Australian identity. The paper explores how Carey’s departure from the traditional Kelly reveals the underlying anxieties about Australianness and masculinity that existed at the time of the novel’s publication, a time during which Australia was reassessing its colonial history. The first chapter of the paper examines True History’s complication of cultural memory. It argues that by problematising Kelly’s Irish cultural memory, our own cultural memory of Kelly is similarly challenged. The second chapter examines Carey’s construction of Kelly’s Irishness more deeply. It argues that Carey’s Kelly is not the emblem of politicised Irishness based on resistance to imperial Britain common to Kelly narratives. Instead, he is less politically aware and also claims a transnational identity. The third chapter explores how Carey’s Kelly diverges from key aspects of the Australian heroic ideal he is used to represent: hetero-masculinity, mateship and heroic failure. Carey’s most striking divergence comes from his unsettling of gender and sexual codes. -

Midnight's Children by Salman Rushdie Discussion Questions

Midnight's Children by Salman Rushdie Discussion Questions 1. Midnight's Children is clearly a work of fiction; yet, like many modern novels, it is presented as an autobiography. How can we tell it isn't? What literary devices are employed to make its fictional status clear? And, bearing in mind the background of very real historical events, can "truth" and "fiction" always be told apart? 2. To what extent has the legacy of the British Empire, as presented in this novel, contributed to the turbulent character of Indian life? 3. Saleem sees himself and his family as a microcosm of what is happening to India. His own life seems so bound up with the fate of the country that he seems to have no existence as an individual; yet, he is a distinct person. How would you characterise Saleem as a human being, set apart from the novel's grand scheme? Does he have a personality? 4. "To understand just one life, you have to swallow the world.... do you wonder, then, that I was a heavy child?" (p. 109). Is it possible, within the limits of a novel, to "understand" a life? 5. At the very heart of Midnight's Children is an act of deception: Mary Pereira switches the birth-tags of the infants Saleem and Shiva. The ancestors of whom Saleem tells us at length are not his biological relations; and yet he continues to speak of them as his forebears. What effect does this have on you, the reader? How easy is it to absorb such a paradox? 6. -

BOOK REVIEWS Michael R. Reder, Ed. Conversations with Salman

258 BOOK REVIEWS Michael R. Reder, ed. Conversations with Salman Rushdie. Jackson: U of Mississippi P, 2000. Pp. xvi, 238. $18.00 pb. The apparently inexorable obsession of journalist and literary critic with the life of Salman Rushdie means it is easy to find studies of this prolific, larger-than-life figure. While this interview collection, part of the Literary Conversations Series, indicates that Rushdie has in fact spo• ken extensively both before, during, and after, his period in hiding, "giving over 100 interviews" (vii), it also substantiates a general aware• ness that despite Rushdie's position at the forefront of contemporary postcolonial literatures, "his writing, like the author himself, is often terribly misjudged by people who, although familiar with his name and situation, have never read a word he has written" (vii). The oppor• tunity to experience Rushdie's unedited voice, interviews re-printed in their entirety as is the series's mandate, is therefore of interest to student, academic and reader alike. Editor Michael Reder has selected twenty interviews, he claims, as the "most in-depth, literate and wide-ranging" (xii). The scope is cer• tainly broad: the interviews, arranged in strict chronological order, cover 1982-99, encompass every geography, and range from those tak• en from published studies to those conducted with the popular me• dia. There is stylistic variation: question-response format, narrative accounts, and extensive, and often poetic, prose introductions along• side traditional transcripts. However, it is a little misleading to infer that this is a collection comprised of hidden gems. There is much here that is commonly known, and interviews taken from existing books or re-published from publications such as Kunapipi and Granta are likely to be available to anybody bar the most casual of enthusiasts. -

Hilary Mantel Papers

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8gm8d1h No online items Hilary Mantel Papers Finding aid prepared by Natalie Russell, October 12, 2007 and Gayle Richardson, January 10, 2018. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens Manuscripts Department 1151 Oxford Road San Marino, California 91108 Phone: (626) 405-2191 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.huntington.org © October 2007 The Huntington Library. All rights reserved. Hilary Mantel Papers mssMN 1-3264 1 Overview of the Collection Title: Hilary Mantel Papers Dates (inclusive): 1980-2016 Collection Number: mssMN 1-3264 Creator: Mantel, Hilary, 1952-. Extent: 11,305 pieces; 132 boxes. Repository: The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens. Manuscripts Department 1151 Oxford Road San Marino, California 91108 Phone: (626) 405-2191 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.huntington.org Abstract: The collection is comprised primarily of the manuscripts and correspondence of British novelist Hilary Mantel (1952-). Manuscripts include short stories, lectures, interviews, scripts, radio plays, articles and reviews, as well as various drafts and notes for Mantel's novels; also included: photographs, audio materials and ephemera. Language: English. Access Hilary Mantel’s diaries are sealed for her lifetime. The collection is open to qualified researchers by prior application through the Reader Services Department. For more information, contact Reader Services. Publication Rights The Huntington Library does not require that researchers request permission to quote from or publish images of this material, nor does it charge fees for such activities. The responsibility for identifying the copyright holder, if there is one, and obtaining necessary permissions rests with the researcher. -

Midnight's Children

Midnight’s Children by SALMAN RUSHDIE SYNOPSIS Born at the stroke of midnight at the exact moment of India’s independence, Saleem Sinai is a special child. However, this coincidence of birth has consequences he is not prepared for: telepathic powers connect him with 1,000 other ‘midnight’s children’ all of whom are endowed with unusual gifts. Inextricably linked to his nation, Saleem’s story is a whirlwind of disasters and triumphs that mirrors the course of modern India at its most impossible and glorious. ‘Huge, vital, engrossing... in all senses a fantastic book’ Sunday Times STARTING POINTS FOR YOUR DISCUSSION Consider the role of marriage in Midnight’s Children. Do you think marriage is portrayed as a positive institution? Do you think Midnight’s Children is a novel of big ideas? How well do you think it carries its themes? If you were to make a film of Midnight’s Children, who would you cast in the principle roles? What do you think of the novel’s ending? Do you think it is affirmative or negative? Is there anything you would change about it? What do you think of the portrayal of women in Midnight’s Children? What is the significance of smell in the novel? Midnight’s Children is narrated in the first person by Saleem, a selfconfessed ‘lover of stories’, who openly admits to getting some facts wrong. Why do you think Rushdie deliberately introduces mistakes into Saleem’s narration? How else does the author explore the theme of the nature of truth? What do you think about the relationship between Padma and Saleem? Consider the way that Padma’s voice differs from Saleem’s. -

The Political and Historical Background of Rushdie's Shame

Quest Journals Journal of Research in Humanities and Social Science Volume 7 ~ Issue 3 (2019)pp.:06-09 ISSN(Online):2321-9467 www.questjournals.org Research Paper The Political and Historical background of Rushdie’s Shame B. Praksh Babu, Dr. B. Krishnaiah Research Scholar Kakatiya UniversityWarangal Asst. Professor, Dept. of English & Coordinator, Entry into Services School of Humanities, University of Hyderabad, Hyderabad - 500 046 TELANGANA STATE, INDIA Corresponding Author: B. Praksh Babu ABSTRACT: The paper discusses the political and historical background portrayed in the novel Shame. Rushdie narrates the history of Pakistan since its partition from India in 1947 to the publication of the novel Shame in1983.Almost thirty six years of Pakistani history is clearly deployed in the novel. Rushdie beautifully knits the story of a newly born state from historical happenings and characters involved in a fictional manner with his literary genius. The style of using language and literary genres is significantly good. He beautifully depicts the contemporary political history and human drama exists in the postcolonial nations by the use of literary genres such as Magical realism, fantasy and symbolism. KEY WORDS: Political, Historical, Shame, Shamelessness, Magical Realism etc., Received 28 March, 2019; Accepted 08 April, 2019 © the Author(S) 2019. Published With Open Access At www.Questjournals.Org I. INTRODUCTION: The story line of Shame alludes to the sub-continental history of post-partition period through complex systems of trans-social connections between the individual and the recorded powers. The text focuses on three related families - the Shakils, the Hyders and the Harappas. The story opens in the fanciful town 'Q' - Quetta in Pakistan with the extraordinary birth of Omar Khayyam, the hero of the novel. -

On Rereading Kazuo Ishiguro Chris Holmes, Kelly Mee Rich

On Rereading Kazuo Ishiguro Chris Holmes, Kelly Mee Rich MFS Modern Fiction Studies, Volume 67, Number 1, Spring 2021, pp. 1-19 (Article) Published by Johns Hopkins University Press For additional information about this article https://muse.jhu.edu/article/786756 [ Access provided at 1 Apr 2021 01:55 GMT from Ithaca College ] Chris Holmes and Kelly Mee Rich 1 On Rereading Kazuo f Ishiguro Chris Holmes and Kelly Mee Rich To consider the career of a single author is necessarily an exercise in rereading. It means revisiting their work, certainly, but also, more carefully, studying how the impress of their authorship evolves over time, and what core elements remain that make them recognizably themselves. Of those authors writing today, Kazuo Ishiguro lends himself exceptionally well to rereading in part because his oeuvre, especially his novels, are so coherent. Featuring first-person narrators reflecting on the remains of their day, these protagonists struggle to come to terms with their participation in structures of harm, and do so with a formal complexity and tonal distance that suggests unreli- ability or a vexed relationship to their own place in the order of things. Ishiguro is also an impeccable re-reader, as the intertextuality of his prose suggests. He convincingly inhabits, as well as cleverly rewrites, existing genres such as the country house novel, the novel of manners, the English boarding school novel, the mystery novel, the bildung- sroman, science fiction, and, most recently, Arthurian fantasy. Artist, detective, pianist, clone: to read Ishiguro always entails rereading in relation to his own oeuvre, as well as to the literary canon. -

Ruth Prawer Jhabvala's Adapted Screenplays

Absorbing the Worlds of Others: Ruth Prawer Jhabvala’s Adapted Screenplays By Laura Fryer Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements of a PhD degree at De Montfort University, Leicester. Funded by Midlands 3 Cities and the Arts and Humanities Research Council. June 2020 i Abstract Despite being a prolific and well-decorated adapter and screenwriter, the screenplays of Ruth Prawer Jhabvala are largely overlooked in adaptation studies. This is likely, in part, because her life and career are characterised by the paradox of being an outsider on the inside: whether that be as a European writing in and about India, as a novelist in film or as a woman in industry. The aims of this thesis are threefold: to explore the reasons behind her neglect in criticism, to uncover her contributions to the film adaptations she worked on and to draw together the fields of screenwriting and adaptation studies. Surveying both existing academic studies in film history, screenwriting and adaptation in Chapter 1 -- as well as publicity materials in Chapter 2 -- reveals that screenwriting in general is on the periphery of considerations of film authorship. In Chapter 2, I employ Sandra Gilbert’s and Susan Gubar’s notions of ‘the madwoman in the attic’ and ‘the angel in the house’ to portrayals of screenwriters, arguing that Jhabvala purposely cultivates an impression of herself as the latter -- a submissive screenwriter, of no threat to patriarchal or directorial power -- to protect herself from any negative attention as the former. However, the archival materials examined in Chapter 3 which include screenplay drafts, reveal her to have made significant contributions to problem-solving, characterisation and tone. -

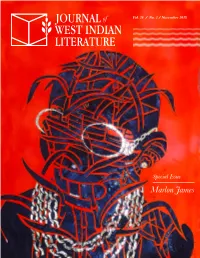

Marlon James Volume 26 Number 2 November 2018

Vol. 26 / No. 2 / November 2018 Special Issue Marlon James Volume 26 Number 2 November 2018 Published by the Departments of Literatures in English, University of the West Indies CREDITS Original image: Sugar Daddy #2 by Leasho Johnson Nadia Huggins (graphic designer) JWIL is published with the financial support of the Departments of Literatures in English of The University of the West Indies Enquiries should be sent to THE EDITORS Journal of West Indian Literature Department of Literatures in English, UWI Mona Kingston 7, JAMAICA, W.I. Tel. (876) 927-2217; Fax (876) 970-4232 e-mail: [email protected] Copyright © 2018 Journal of West Indian Literature ISSN (online): 2414-3030 EDITORIAL COMMITTEE Evelyn O’Callaghan (Editor in Chief) Michael A. Bucknor (Senior Editor) Lisa Outar (Senior Editor) Glyne Griffith Rachel L. Mordecai Kevin Adonis Browne BOOK REVIEW EDITOR Antonia MacDonald EDITORIAL BOARD Edward Baugh Victor Chang Alison Donnell Mark McWatt Maureen Warner-Lewis EDITORIAL ADVISORY BOARD Laurence A. Breiner Rhonda Cobham-Sander Daniel Coleman Anne Collett Raphael Dalleo Denise deCaires Narain Curdella Forbes Aaron Kamugisha Geraldine Skeete Faith Smith Emily Taylor THE JOURNAL OF WEST INDIAN LITERATURE has been published twice-yearly by the Departments of Literatures in English of the University of the West Indies since October 1986. JWIL originated at the same time as the first annual conference on West Indian Literature, the brainchild of Edward Baugh, Mervyn Morris and Mark McWatt. It reflects the continued commitment of those who followed their lead to provide a forum in the region for the dissemination and discussion of our literary culture. -

Storytellers, Dreamers, Rebels: the Concept of Agency in Selected Novels by Peter Carey

Faculty of Linguistics, Literature and Cultural Studies Institute of English and American Studies Chair of English Literary Studies Dissertation Storytellers, Dreamers, Rebels: The Concept of Agency in Selected Novels by Peter Carey by Sebastian Jansen A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Supervisors: Prof. Dr. Stefan Horlacher, Prof. Dr. Thomas Kühn, Prof. Dr. Bill Ashcroft Technische Universität Dresden, Faculty of Linguistics, Literature and Cultural Studies 29 July 2016 Table of Contents 1. Introduction ......................................................................................................................................... 4 2. Literary Overview of Carey’s Writing ................................................................................................ 18 3. Agency in Carey’s Writing: Three ‘Carey Themes’ ............................................................................ 29 4. Agency ............................................................................................................................................... 49 4.1. Important Terminology .............................................................................................................. 49 4.2. Agency: A New Phenomenon? .................................................................................................... 53 4.3. The Ancient Sources of Agency ................................................................................................... 62 4.4.