Disintegration and Integration in East-Central Europe

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reigniting Growth in Central and Eastern Europe Eastern and Central in Growth Dawn:A New Reigniting

McKinsey Global Institute McKinsey Global Institute A new dawn: ReignitingA new dawn: growth in Central and Eastern Europe December 2013 A new dawn: Reigniting growth in Central and Eastern Europe The McKinsey Global Institute The McKinsey Global Institute (MGI), the business and economics research arm of McKinsey & Company, was established in 1990 to develop a deeper understanding of the evolving global economy. MGI’s mission is to provide leaders in the commercial, public, and social sectors with the facts and insights on which to base management and policy decisions. MGI research combines the disciplines of economics and management, employing the analytical tools of economics with the insights of business leaders. Its “micro-to-macro” methodology examines microeconomic industry trends to better understand the broad macroeconomic forces affecting business strategy and public policy. MGI’s in-depth reports have covered more than 20 countries and 30 industries. Current research focuses on six themes: productivity and growth; the evolution of global financial markets; the economic impact of technology and innovation; natural resources; the future of work; and urbanisation. Recent reports have assessed job creation, resource productivity, cities of the future, and the impact of the Internet. The partners of McKinsey fund MGI’s research; it is not commissioned by any business, government, or other institution. For further information about MGI and to download reports, please visit www.mckinsey.com/mgi. McKinsey in Central and Eastern Europe McKinsey & Company opened its first offices in Central and Eastern Europe in the early 1990s, soon after the momentous democratic changes in the region. McKinsey played an active role in the region’s economic rebirth, working with governments, nonprofits, and cultural institutions, as well as leading business organisations. -

30Years 1953-1983

30Years 1953-1983 Group of the European People's Party (Christian -Demoeratie Group) 30Years 1953-1983 Group of the European People's Party (Christian -Demoeratie Group) Foreword . 3 Constitution declaration of the Christian-Democratic Group (1953 and 1958) . 4 The beginnings ............ ·~:.................................................. 9 From the Common Assembly to the European Parliament ........................... 12 The Community takes shape; consolidation within, recognition without . 15 A new impetus: consolidation, expansion, political cooperation ........................................................... 19 On the road to European Union .................................................. 23 On the threshold of direct elections and of a second enlargement .................................................... 26 The elected Parliament - Symbol of the sovereignty of the European people .......... 31 List of members of the Christian-Democratic Group ................................ 49 2 Foreword On 23 June 1953 the Christian-Democratic Political Group officially came into being within the then Common Assembly of the European Coal and Steel Community. The Christian Democrats in the original six Community countries thus expressed their conscious and firm resolve to rise above a blinkered vision of egoistically determined national interests and forge a common, supranational consciousness in the service of all our peoples. From that moment our Group, whose tMrtieth anniversary we are now celebrating together with thirty years of political -

The Changing Depiction of Prussia in the GDR

The Changing Depiction of Prussia in the GDR: From Rejection to Selective Commemoration Corinna Munn Department of History Columbia University April 9, 2014 Acknowledgments I would like to thank my advisor, Volker Berghahn, for his support and guidance in this project. I also thank my second reader, Hana Worthen, for her careful reading and constructive advice. This paper has also benefited from the work I did under Wolfgang Neugebauer at the Humboldt University of Berlin in the summer semester of 2013, and from the advice of Bärbel Holtz, also of Humboldt University. Table of Contents 1. Introduction……………………………………………………………………….1 2. Chronology and Context………………………………………………………….4 3. The Geschichtsbild in the GDR…………………………………………………..8 3.1 What is a Geschichtsbild?..............................................................................8 3.2 The Function of the Geschichtsbild in the GDR……………………………9 4. Prussia’s Changing Role in the Geschichtsbild of the GDR…………………….11 4.1 1945-1951: The Post-War Period………………………………………….11 4.1.1 Historiography and Publications……………………………………11 4.1.2 Public Symbols and Events: The fate of the Berliner Stadtschloss…14 4.1.3 Film: Die blauen Schwerter………………………………………...19 4.2 1951-1973: Building a Socialist Society…………………………………...22 4.2.1 Historiography and Publications……………………………………22 4.2.2 Public Symbols and Events: The Neue Wache and the demolition of Potsdam’s Garnisonkirche…………………………………………..30 4.2.3 Film: Die gestohlene Schlacht………………………………………34 4.3 1973-1989: The Rediscovery of Prussia…………………………………...39 4.3.1 Historiography and Publications……………………………………39 4.3.2 Public Symbols and Events: The restoration of the Lindenforum and the exhibit at Sans Souci……………………………………………42 4.3.3 Film: Sachsens Glanz und Preußens Gloria………………………..45 5. -

Political Visions and Historical Scores

Founded in 1944, the Institute for Western Affairs is an interdis- Political visions ciplinary research centre carrying out research in history, political and historical scores science, sociology, and economics. The Institute’s projects are typi- cally related to German studies and international relations, focusing Political transformations on Polish-German and European issues and transatlantic relations. in the European Union by 2025 The Institute’s history and achievements make it one of the most German response to reform important Polish research institution well-known internationally. in the euro area Since the 1990s, the watchwords of research have been Poland– Ger- many – Europe and the main themes are: Crisis or a search for a new formula • political, social, economic and cultural changes in Germany; for the Humboldtian university • international role of the Federal Republic of Germany; The end of the Great War and Stanisław • past, present, and future of Polish-German relations; Hubert’s concept of postliminum • EU international relations (including transatlantic cooperation); American press reports on anti-Jewish • security policy; incidents in reborn Poland • borderlands: social, political and economic issues. The Institute’s research is both interdisciplinary and multidimension- Anthony J. Drexel Biddle on Poland’s al. Its multidimensionality can be seen in published papers and books situation in 1937-1939 on history, analyses of contemporary events, comparative studies, Memoirs Nasza Podróż (Our Journey) and the use of theoretical models to verify research results. by Ewelina Zaleska On the dispute over the status The Institute houses and participates in international research of the camp in occupied Konstantynów projects, symposia and conferences exploring key European questions and cooperates with many universities and academic research centres. -

European Left Info Flyer

United for a left alternative in Europe United for a left alternative in Europe ”We refer to the values and traditions of socialism, com- munism and the labor move- ment, of feminism, the fem- inist movement and gender equality, of the environmental movement and sustainable development, of peace and international solidarity, of hu- man rights, humanism and an- tifascism, of progressive and liberal thinking, both national- ly and internationally”. Manifesto of the Party of the European Left, 2004 ABOUT THE PARTY OF THE EUROPEAN LEFT (EL) EXECUTIVE BOARD The Executive Board was elected at the 4th Congress of the Party of the European Left, which took place from 13 to 15 December 2013 in Madrid. The Executive Board consists of the President and the Vice-Presidents, the Treasurer and other Members elected by the Congress, on the basis of two persons of each member party, respecting the principle of gender balance. COUNCIL OF CHAIRPERSONS The Council of Chairpersons meets at least once a year. The members are the Presidents of all the member par- ties, the President of the EL and the Vice-Presidents. The Council of Chairpersons has, with regard to the Execu- tive Board, rights of initiative and objection on important political issues. The Council of Chairpersons adopts res- olutions and recommendations which are transmitted to the Executive Board, and it also decides on applications for EL membership. NETWORKS n Balkan Network n Trade Unionists n Culture Network Network WORKING GROUPS n Central and Eastern Europe n Africa n Youth n Agriculture n Migration n Latin America n Middle East n North America n Peace n Communication n Queer n Education n Public Services n Environment n Women Trafficking Member and Observer Parties The Party of the European Left (EL) is a political party at the Eu- ropean level that was formed in 2004. -

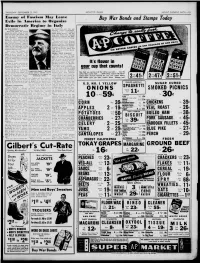

Gilbert S Cut-Rate I

THURSDAY—SEPTEMBER 23, 1943 MONITOR LEADER MOUNT CLEMENS, MICH 13 Ent k inv oh* May L« kav«* Buy War Bonds and Stamps Today Exile in i\meriea to Orijaiiixe w • ll€kiiioi*ralir hi Italy BY KAY HALLE ter Fiammetta. and his son Written for M A Service Sforzino reached Bordeaux, Within 25 year* the United where they m* to board a States has Riven refuge to two Dutch tramp steamer. For five great European Democrats who long days before they reached were far from the end of their Falmouth in England, the Sfor- rope politically. Thomas Mas- zas lived on nothing but orang- aryk. the Czech patriot, after es. a self-imposed exile on spending It war his old friend, Winston shores, return ! after World our Churchill, who finally received to it War I his homrlan after Sforza in London. the The Battle of had been freed from German Britain yoke—as the had commenced. Church- the President of approved to pro- newly-formed Republic—- ill Sforza side i Czech ceed to the United States and after modeled our own. keep the cause of Italian democ- Now, with the collapse of racy aflame. famous exile Italy, another HEADS “FREE ITALIANS” He -* an... JC. -a seems to be 01. the march. J two-year Sforza’-i American . is Count Carlo Sforza, for 20 exile has been spent in New’ years the uncompromising lead- apartment—- opposition York in a modest er of the Democratic that is, he not touring to Italy when is to Fascism. His return the country lecturing and or- imminent seem gazing the affairs of the 300,- Sforza is widely reg rded as in 000 It's flnuor Free Italians in the Western the one Italian who could re- Hemisphere, w hom \e leads construct a democratic form of His New York apartment is government for Italy. -

The Cold War and East-Central Europe, 1945–1989

FORUM The Cold War and East-Central Europe, 1945–1989 ✣ Commentaries by Michael Kraus, Anna M. Cienciala, Margaret K. Gnoinska, Douglas Selvage, Molly Pucci, Erik Kulavig, Constantine Pleshakov, and A. Ross Johnson Reply by Mark Kramer and V´ıt Smetana Mark Kramer and V´ıt Smetana, eds. Imposing, Maintaining, and Tearing Open the Iron Curtain: The Cold War and East-Central Europe, 1945–1989. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books, 2014. 563 pp. $133.00 hardcover, $54.99 softcover, $54.99 e-book. EDITOR’S NOTE: In late 2013 the publisher Lexington Books, a division of Rowman & Littlefield, put out the book Imposing, Maintaining, and Tearing Open the Iron Curtain: The Cold War and East-Central Europe, 1945–1989, edited by Mark Kramer and V´ıt Smetana. The book consists of twenty-four essays by leading scholars who survey the Cold War in East-Central Europe from beginning to end. East-Central Europe was where the Cold War began in the mid-1940s, and it was also where the Cold War ended in 1989–1990. Hence, even though research on the Cold War and its effects in other parts of the world—East Asia, South Asia, Latin America, Africa—has been extremely interesting and valuable, a better understanding of events in Europe is essential to understand why the Cold War began, why it lasted so long, and how it came to an end. A good deal of high-quality scholarship on the Cold War in East-Central Europe has existed for many years, and the literature on this topic has bur- geoned in the post-Cold War period. -

Lecture 27 Epilogue How Far Does the Past Dominate Polish Politics Today? 'Choose the Future' Election Slogan of Alexander K

- 1 - Lecture 27 Epilogue How far does the past dominate Polish politics today? ‘Choose the future’ Election slogan of Alexander Kwaśniewski in 1996. ‘We are today in the position of Andrzej Gołota: after seven rounds, we are winning on points against our historical fatalism. As rarely in our past - today almost everything depends on us ourselves... In the next few years, Poland’s fate for the succeeding half- century will be decided. And yet Poland has the chance - like Andrzej Gołota, to waste its opportunity. We will not enter NATO of the European Union if we are a country beset by a domestic cold war, a nation so at odds with itself that one half wants to destroy the other. Adam Michnik, ‘Syndrom Gołoty’, Gazeta Świąteczna, 22 December 1996 ‘I do not fear the return of communism, but there is a danger of new conflicts between chauvinism and nationalist extremism on the one hand and tolerance, liberalism and Christian values on the other’ Władysław Bartoszewski on the award to him of the Heinrich Heine prize, December 1996 1. Introduction: History as the Means for Articulating Political Orientations In Poland, as in most countries which have been compelled to struggle to regain their lost independence, an obsessive involvement with the past and a desire to derive from it lessons of contemporary relevance have long been principal characteristics of the political culture. Polish romantic nationalism owed much to Lelewel’s concept of the natural Polish predilection for democratic values. The Polish nation was bound, he felt, to struggle as ‘ambassador to humanity’ and, through its suffering, usher in an era on universal liberty. -

Ius Novum 3-18.Indd

ISSN 1897-5577 Ius Novum Vol. 12 Number 3 2018 july–september DOI: 10.26399/iusnovum.v12.3.2018 english version QUARTERLY OF THE FACULTY OF LAW AND ADMINISTRATION OF LAZARSKI UNIVERSITY Warsaw 2018 RADA NAUKOWA / ADVISORY BOARD President: Prof., Maria Kruk-Jarosz, PhD hab., Lazarski University in Warsaw (Poland) Prof. Sylvie Bernigaud, PhD hab., Lumière University Lyon 2 (France) Prof. Vincent Correia, PhD hab., University of Paris-Sud, University of Poitiers (France) Prof. Bertil Cottier, PhD hab., Università della Svizzera italiana of Lugano (Switzerland) Prof. Regina Garcimartín Montero, PhD hab., University of Zaragoza (Spain) Prof. Juana María Gil Ruiz, PhD, University of Granada (Spain) Prof. Stephan Hobe, PhD hab., University of Cologne (Germany) Prof. Brunon Hołyst, PhD hab., honoris causa doctor, Lazarski University in Warsaw (Poland) Prof. Michele Indellicato, PhD hab., University of Bari Aldo Moro (Italy) Prof. Hugues Kenfack, PhD hab., Toulouse 1 Capitole University of Toulouse (France) Rev. Prof. Franciszek Longchamps de Bérier, PhD hab., Jagiellonian University in Kraków (Poland) Prof. Pablo Mendes de Leon, PhD hab., Leiden University (Netherlands) Prof. Adam Olejniczak, PhD hab., Adam Mickiewicz University in Poznań (Poland) Prof. Ferdinando Parente, PhD, University of Bari Aldo Moro (Italy) Prof. Grzegorz Rydlewski, PhD hab., University of Warsaw (Poland) Prof. Vinai Kumar Singh, PhD hab., New Delhi, Indian Society of International Law (India) Prof. Gintaras Švedas, PhD hab., Vilnius University (Lithuania) Prof. Anita Ušacka, PhD hab., judge of the International Criminal Court in the Hague (Netherlands) Ewa Weigend, PhD, Max-Planck Institute for Foreign and International Criminal Law in Freiburg (Germany) REDAKCJA / EDITORIAL BOARD Editor-in-Chief: Prof. -

Czechoslovak-Polish Relations 1918-1968: the Prospects for Mutual Support in the Case of Revolt

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 1977 Czechoslovak-Polish relations 1918-1968: The prospects for mutual support in the case of revolt Stephen Edward Medvec The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Medvec, Stephen Edward, "Czechoslovak-Polish relations 1918-1968: The prospects for mutual support in the case of revolt" (1977). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 5197. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/5197 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CZECHOSLOVAK-POLISH RELATIONS, 191(3-1968: THE PROSPECTS FOR MUTUAL SUPPORT IN THE CASE OF REVOLT By Stephen E. Medvec B. A. , University of Montana,. 1972. Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts UNIVERSITY OF MONTANA 1977 Approved by: ^ .'■\4 i Chairman, Board of Examiners raduat'e School Date UMI Number: EP40661 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. -

Russia's Hostile Measures in Europe

Russia’s Hostile Measures in Europe Understanding the Threat Raphael S. Cohen, Andrew Radin C O R P O R A T I O N For more information on this publication, visit www.rand.org/t/RR1793 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available for this publication. ISBN: 978-1-9774-0077-2 Published by the RAND Corporation, Santa Monica, Calif. © Copyright 2019 RAND Corporation R® is a registered trademark. Limited Print and Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law. This representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for noncommercial use only. Unauthorized posting of this publication online is prohibited. Permission is given to duplicate this document for personal use only, as long as it is unaltered and complete. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of its research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please visit www.rand.org/pubs/permissions. The RAND Corporation is a research organization that develops solutions to public policy challenges to help make communities throughout the world safer and more secure, healthier and more prosperous. RAND is nonprofit, nonpartisan, and committed to the public interest. RAND’s publications do not necessarily reflect the opinions of its research clients and sponsors. Support RAND Make a tax-deductible charitable contribution at www.rand.org/giving/contribute www.rand.org Preface This report is the collaborative and equal effort of the coauthors, who are listed in alphabetical order. The report documents research and analysis conducted through 2017 as part of a project entitled Russia, European Security, and “Measures Short of War,” sponsored by the Office of the Deputy Chief of Staff, G-3/5/7, U.S. -

Appendix: Einaudi, President of the Italian Republic (1948–1955) Message After the Oath*

Appendix: Einaudi, President of the Italian Republic (1948–1955) Message after the Oath* At the general assembly of the House of Deputies and the Senate of the Republic, on Wednesday, 12 March 1946, the President of the Republic read the following message: Gentlemen: Right Honourable Senators and Deputies! The oath I have just sworn, whereby I undertake to devote myself, during the years awarded to my office by the Constitution, to the exclusive service of our common homeland, has a meaning that goes beyond the bare words of its solemn form. Before me I have the shining example of the illustrious man who was the first to hold, with great wisdom, full devotion and scrupulous impartiality, the supreme office of head of the nascent Italian Republic. To Enrico De Nicola goes the grateful appreciation of the whole of the people of Italy, the devoted memory of all those who had the good fortune to witness and admire the construction day by day of the edifice of rules and traditions without which no constitution is destined to endure. He who succeeds him made repeated use, prior to 2 June 1946, of his right, springing from the tradition that moulded his sentiment, rooted in ancient local patterns, to an opinion on the choice of the best regime to confer on Italy. But, in accordance with the promise he had made to himself and his electors, he then gave the new republican regime something more than a mere endorsement. The transition that took place on 2 June from the previ- ous to the present institutional form of the state was a source of wonder and marvel, not only by virtue of the peaceful and law-abiding manner in which it came about, but also because it offered the world a demonstration that our country had grown to maturity and was now ready for democracy: and if democracy means anything at all, it is debate, it is struggle, even ardent or * Message read on 12 March 1948 and republished in the Scrittoio del Presidente (1948–1955), Giulio Einaudi (ed.), 1956.