University Micrdrilms International 300 N

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mark Twain's the Adventures of Huckleberry Finn in the Contemporary English Classroom

Mark Twain's The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn in the Contemporary English Classroom Senior Paper Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For a Degree Bachelor of Arts with A Major in Literature at The University of North Carolina at Asheville Fall 2009 By HOGAN CARRINGER _____________________ Thesis Director Dr. Blake Hobby _____________________ Thesis Advisor Dr. Merritt Moseley Carringer 2 When choosing a narrator for a work, why does an author decide that a child’s voice would suit the narrative best? Is it the child’s unsullied and unvarnished perspective because of his age? Could it be a child’s lack of experience with life in general which help to explain characters’ mistakes and plot complications? These are all important questions to ponder while analyzing Mark Twain’s novel The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. In fact, by placing critics of the novel in a dialogue, we can see both why the work has been and will continue to be controversial and why this work should remain a part of the American literary canon. The connection between the two ideas is that readers who find the novel unacceptable often do so because they do not read it in a sophisticated way that acknowledges Huck's unreliability, instead thinking that he speaks for the novel's values, even in his offhand racist comments. To establish his unreliability is to separate the novel's racial attitudes from those of its narrator. A Bildungsroman set in the pre-slavery days of America, the work follows the travails of a ten year old boy named Huckleberry Finn and his runaway slave friend Jim as they journey down the Mississippi River in search of freedom from a restrictive and hostile society. -

Mark Twain's Huckleberry Finn As Anti Racist Novel

Journal of Literature, Languages and Linguistics www.iiste.org ISSN 2422-8435 An International Peer-reviewed Journal Vol.46, 2018 Mark Twain’s Huckleberry Finn as Anti Racist Novel Ass.Lecturer Fahmi Salim Hameed Imam Kadhim college for Islamic science university, Baghdad , Iraq "Man is the only Slave. And he is the only animal who enslaves. He has always been a slave in one form or another, and has always held other slaves in bondage under him in one way or another.” - Mark Twain Abstract Mark Twain, the American author and satirist well known for his novels Huckleberry Finn and The Adventures of Tom Sawyer , grew up in Missouri, which is a slave state and which later provided the setting for a couple of his novels. Tom Sawyer and Huck Finn are the two most well-known characters among American readers that Mark Twain created. As a matter of fact, they are the most renowned pair in all of American literature. Twain’s father worked as a judge by profession, but he also worked in slave-trade sometimes. His uncle, John Quarles, owned 20 slaves; so from quite an early age, Twain grew up witnessing the practice of slave-trade whenever he spent summer vacations at his uncle's house. Many of his readers and critics have argued on his being a racist. Some call him an “Unexcusebale racist” and some say that Twain is no where even close to being a racist. Growing up in the times of slave trade, Twain had witnessed a lot of brutality and violence towards the African slaves. -

Huckleberry Finn's Cure for Warts

HUCKLEBERRY FINN’S CURE FOR WARTS A Humorous Reading by Mark Twain Wetmore Declamation Bureau Box 2695 Sioux City, IA 51106 www.wetmoredeclamation.com Email: [email protected] CAUTION: Wetmore Declamation Bureau material is protected by United States copyright law and conventions. None of our material may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means-electronic, mechanical, photocopy, recording, or any other-without prior permission. No trademark, copyright or other notice may be removed or changed. All rights reserved. Violators will be prosecuted to the full extent of the law. HUCKLEBERRY FINN’S CURE FOR WARTS A Humorous Reading Mark Twain From “The Adventures of Tom Sawyer” ISBN 1-60045-088-1 Huckleberry Finn, son of the town drunkard, was dreaded by all the mothers of the town, because he was idle and lawless—and because all their children admired him so, and wished they dared to be like him. Tom Sawyer, like the rest of the respectable boys, was under strict orders not to play with him. So he played with him every time he got a chance. Huckleberry did not have to go to school or to church; he could go fishing or swimming when and where he chose, and stay as long as it suited him; nobody forbade him to fight; he was always the first boy that went barefoot in the spring and the last to resume leather in the fall; he never had to wash, nor put on clean clothes. In a word, everything that goes to make life precious, that boy had. -

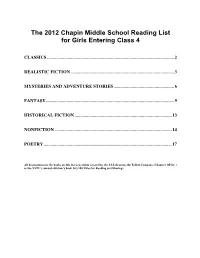

The 2012 Chapin Middle School Reading List for Girls Entering Class 4

The 2012 Chapin Middle School Reading List for Girls Entering Class 4 CLASSICS ............................................................................................................... 2 REALISTIC FICTION .......................................................................................... 3 MYSTERIES AND ADVENTURE STORIES ..................................................... 6 FANTASY ................................................................................................................ 9 HISTORICAL FICTION ..................................................................................... 13 NONFICTION ...................................................................................................... 14 POETRY ................................................................................................................ 17 All descriptions for the books on this list were either created by the LS Librarian, the Follett Company (Chapin’s OPAC ) or the NYPL’s annual children’s book list (100 Titles for Reading and Sharing). Classics Aiken, Joan. Wolves of Willoughby Chase. Two young girls are sent to live on an isolated country estate where they find themselves in the clutches of an evil governess. Alcott, Louisa May Little Women Follow the lives of four sisters in nineteenth-century New England. Baum, L. Frank. The Wizard Of Oz. An elegant and rich story about a girl, her friends, and a humbug wizard. Burnett, Frances Hodgson. The Secret Garden. A young orphan named Mary is sent to live at a creepy English estate -

Dr. Albert W. Johnson June 29-30, 2009 Interviewed by Susan Resnik for San Diego State University 208 Minutes of Recording Total PART 1 of 3 PARTS

Dr. Albert W. Johnson June 29-30, 2009 interviewed by Susan Resnik for San Diego State University 208 minutes of recording total PART 1 OF 3 PARTS SUSAN RESNIK: This is Susan Resnik. Today is June 29, 2009. I’m in the lovely home of Dr. Albert W. Johnson, in Portland, Oregon. We are going to be doing his oral history as part of the project funded by the Jane and John Adams mini- grant. Good morning, Dr. Johnson. ALBERT W. JOHNSON: Good morning, Susan. SR: Dr. Johnson, you certainly made so many contributions to San Diego State University, spanning the presidencies of Dr. Love, Dr. Golding, and Dr. Day, and contributed so much, but we’d like to go back and start at the beginning. I’d like to know when and where you were born. Could you tell me a little about your early years? AWJ: Yes, thank you. I was born in a little town by the name of Belvidere, Illinois, a small agricultural community in northern Illinois, on July 29, 1926; and lived there all the time I was growing up, until I went into the military, which I can talk about later if you like; and then never did go back to live. And now, nobody from my family lives in Belvidere, Illinois. I had two parents, of course, Mother and Father. My mother was the daughter of a Lutheran minister in Belvidere, and played a very active role in the church herself. She was the organist, the choir directory, played the piano for all kinds of things, and of course raised the children. -

The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn

T HE G LENCOE L ITERATURE L IBRARY Study Guide for The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn by Mark Twain A i Meet Mark Twain Hannibal to work as a printer’s assistant. He held printing jobs in New York, Pennsylvania, and Iowa. Then, when he was twenty-one, he returned to the Mississippi River to train for the job he wanted above all others: steamboat pilot. A few years later, he became a licensed pilot, but his time as a pilot was cut short by the start of the Civil War, in 1861. After a two-week stint in the Confederate army, Clemens joined his brother in Carson City, Nevada. There, Clemens began to write humorous sketches and tall tales for the local newspaper. In February 1863, he first used the pseudonym, or pen I was born the 30th of November, 1835, in the name, that would later be known by readers almost invisible village of Florida, Monroe County, throughout the world. It was a riverboating term Missouri. The village contained a hundred for water two fathoms, or twelve feet, deep: “Mark people and I increased the population by Twain.” 1 percent. It is more than many of the best men Clemens next worked as a miner near San in history could have done for a town. Francisco. In 1865 he published in a national magazine a tall tale he had heard in the mine- —The Autobiography of Mark Twain fields—“The Celebrated Jumping Frog of Calaveras County.” It was an instant success. ark Twain, whose real name was Samuel Later, he traveled to Hawaii, Europe, and the M Clemens, was in many ways a self-made Middle East. -

Literary Destinations

LITERARY DESTINATIONS: MARK TWAIN’S HOUSES AND LITERARY TOURISM by C2009 Hilary Iris Lowe Submitted to the graduate degree program in American studies and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. _________________________________________ Dr. Cheryl Lester _________________________________________ Dr. Susan K. Harris _________________________________________ Dr. Ann Schofield _________________________________________ Dr. John Pultz _________________________________________ Dr. Susan Earle Date Defended 11/30/2009 2 The Dissertation Committee for Hilary Iris Lowe certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Literary Destinations: Mark Twain’s Houses and Literary Tourism Committee: ____________________________________ Dr. Cheryl Lester, Chairperson Accepted 11/30/2009 3 Literary Destinations Americans are obsessed with houses—their own and everyone else’s. ~Dell Upton (1998) There is a trick about an American house that is like the deep-lying untranslatable idioms of a foreign language— a trick uncatchable by the stranger, a trick incommunicable and indescribable; and that elusive trick, that intangible something, whatever it is, is the something that gives the home look and the home feeling to an American house and makes it the most satisfying refuge yet invented by men—and women, mainly by women. ~Mark Twain (1892) 4 TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 5 ABSTRACT 7 PREFACE 8 INTRODUCTION: 16 Literary Homes in the United -

Critics' Views of the Character of Jim in Huckleberry Finn Elizabeth J

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 1977 Critics' views of the character of Jim in Huckleberry Finn Elizabeth J. Gifford Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Gifford, Elizabeth J., "Critics' views of the character of Jim in Huckleberry Finn " (1977). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 6965. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/6965 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Critics' views of the character of Jim in Huckleberry Finn by Elizabeth J. Gifford A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Partial Fulfillment of The Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS Major; English Signatures have been redacted for privacy Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 1977 One hundred years have passed since Samuel Clemens began creating his masterpiece. Huckleberry Finn. The main charac ters in this novel are a homeless rebel of a boy who is (or believes he is) running away from his murderous father/ and a frightened slave who is running away from a greedy old woman owner who was about to sell him and separate him from his family. Much has been written about this work—ranging from the highest praise to scathing criticism. -

Mark Twain, the Dialogic Imagination, and the American Classroom Drew

Kansas English, Vol. 98, No. 1 (2017) Mark Twain, the Dialogic Imagination, and the American Classroom Drew Clifton Colcher Abstract Mark Twain is often read as a provincial realist or naturalist whose works are disseminated in simplified versions as children’s stories or seen as humorous social criticism of the southern United States and its dialects. This article focuses on two of Twain’s novels—A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court (1889) and No. 44, the Mysterious Stranger (published posthumously with various titles)—in order to focus on the more modern, less provincial, novelistic aspects of Twain’s writing. The theories of Mikhail Bakhtin provide the background for a characterization of the novelistic nature of these works in an effort to re-focus Twain criticism away from realist or naturalist analysis and toward semiotic and structural considerations. This essay functions as an introductory-level presentation of Bakhtinian analysis and Twain criticism, as well as a reimagining of the role of Twain’s writings in the classroom, especially in light of recent controversies surrounding the language used in works like The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. Of paramount importance to this argument are the temporal, spatial, formal and thematic coordinates of the two books, and the assertion that they conform to Bakhtin’s conception of the novel and how it radically differs from other forms. Keywords Mark Twain, Mikhail Bakhtin, semiotics, novelism, American literature, literary theory, pedagogy, literary criticism, modernism, realism, structuralism Novels like A Connecticut Yankee at King Arthur’s Court and No. 44, The Mysterious Stranger raise problematic questions for Twain scholars because they directly approach more philosophical human concerns while, at times, casting off the sarcastically humorous facade that characterizes Twain’s work in general. -

On the Road with President Woodrow Wilson by Richard F

On the Road with President Woodrow Wilson By Richard F. Weingroff Table of Contents Table of Contents .................................................................................................... 2 Woodrow Wilson – Bicyclist .................................................................................. 1 At Princeton ............................................................................................................ 5 Early Views on the Automobile ............................................................................ 12 Governor Wilson ................................................................................................... 15 The Atlantic City Speech ...................................................................................... 20 Post Roads ......................................................................................................... 20 Good Roads ....................................................................................................... 21 President-Elect Wilson Returns to Bermuda ........................................................ 30 Last Days as Governor .......................................................................................... 37 The Oath of Office ................................................................................................ 46 President Wilson’s Automobile Rides .................................................................. 50 Summer Vacation – 1913 ..................................................................................... -

Chemung County Age-Friendly Community Action Plan Evaluation

Chemung County Age-Friendly Community Action Plan Evaluation 2015 – 2017 Submitted 2/15/18 Table of Contents Chemung County Age-Friendly Community Coalition 2 Executive Summary 4 Outdoor Spaces and Buildings 7 Transportation 23 Housing 32 Social Participation 43 Respect and Social Inclusion 45 Civic Participation and Employment 50 Communication and Information 54 Community Support and Health Services 59 1 Chemung County Age-Friendly Community Coalition December 2017 Kym Beckman-Draht/Cindy McInerney (Able 2) Pam Brown (Dept. of Aging & Long Term Care) Tara Burke (Chamber of Commerce) Dawn Bush/Rebecca Becraft (Health Dept.) Katie Coletta (Chemung Canal Trust Company) Liz Corveleyn (Town of Big Flats) Sam David (Retired past Director Dept. of Aging & Long Term Care) Marleah Denkenberger (Alzheimer’s Association Southern Tier Satellite) Dave Ellis (Town of Southport) Michele Fitch (Appleridge Senior Living) Allyson Graf (Elmira College) Jim Hackett (Dept. of Aging Advisory Council) Darlene Ike (Meals on Wheels of Chemung County, Inc.) Michele Johnson (YWCA) Evanna Koska (Dept. of Aging Advisory Council) Anita Lewis/Tina Brown (EOP) Mark Lisi (Food Bank of the Southern Tier) Dan Mandell (City of Elmira) Craig Mennig/Trisha Rude (The Arc of Chemung) Mary Mosteller (CareFirst – formerly Southern Tier Hospice and Palliative Care) Allison O’Dell (AIM Independent Living Center) Felix Perez (First Presbyterian Church of Elmira) Bridget Petrillose/Tim Driscoll (GST BOCES) Caroline Poppendeck (Chemung Count Library District) Ron Rehner (AARP Chapter -

Book Title Author Reading Level Approx. Grade Level

Approx. Reading Book Title Author Grade Level Level Anno's Counting Book Anno, Mitsumasa A 0.25 Count and See Hoban, Tana A 0.25 Dig, Dig Wood, Leslie A 0.25 Do You Want To Be My Friend? Carle, Eric A 0.25 Flowers Hoenecke, Karen A 0.25 Growing Colors McMillan, Bruce A 0.25 In My Garden McLean, Moria A 0.25 Look What I Can Do Aruego, Jose A 0.25 What Do Insects Do? Canizares, S.& Chanko,P A 0.25 What Has Wheels? Hoenecke, Karen A 0.25 Cat on the Mat Wildsmith, Brain B 0.5 Getting There Young B 0.5 Hats Around the World Charlesworth, Liza B 0.5 Have you Seen My Cat? Carle, Eric B 0.5 Have you seen my Duckling? Tafuri, Nancy/Greenwillow B 0.5 Here's Skipper Salem, Llynn & Stewart,J B 0.5 How Many Fish? Cohen, Caron Lee B 0.5 I Can Write, Can You? Stewart, J & Salem,L B 0.5 Look, Look, Look Hoban, Tana B 0.5 Mommy, Where are You? Ziefert & Boon B 0.5 Runaway Monkey Stewart, J & Salem,L B 0.5 So Can I Facklam, Margery B 0.5 Sunburn Prokopchak, Ann B 0.5 Two Points Kennedy,J. & Eaton,A B 0.5 Who Lives in a Tree? Canizares, Susan et al B 0.5 Who Lives in the Arctic? Canizares, Susan et al B 0.5 Apple Bird Wildsmith, Brain C 1 Apples Williams, Deborah C 1 Bears Kalman, Bobbie C 1 Big Long Animal Song Artwell, Mike C 1 Brown Bear, Brown Bear What Do You See? Martin, Bill C 1 Found online, 7/20/2012, http://home.comcast.net/~ngiansante/ Approx.