An Introduction to Linux/Unix at Denison

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ethereal Developer's Guide Draft 0.0.2 (15684) for Ethereal 0.10.11

Ethereal Developer's Guide Draft 0.0.2 (15684) for Ethereal 0.10.11 Ulf Lamping, Ethereal Developer's Guide: Draft 0.0.2 (15684) for Ethere- al 0.10.11 by Ulf Lamping Copyright © 2004-2005 Ulf Lamping Permission is granted to copy, distribute and/or modify this document under the terms of the GNU General Public License, Version 2 or any later version published by the Free Software Foundation. All logos and trademarks in this document are property of their respective owner. Table of Contents Preface .............................................................................................................................. vii 1. Foreword ............................................................................................................... vii 2. Who should read this document? ............................................................................... viii 3. Acknowledgements ................................................................................................... ix 4. About this document .................................................................................................. x 5. Where to get the latest copy of this document? ............................................................... xi 6. Providing feedback about this document ...................................................................... xii I. Ethereal Build Environment ................................................................................................14 1. Introduction .............................................................................................................15 -

A.5.1. Linux Programming and the GNU Toolchain

Making the Transition to Linux A Guide to the Linux Command Line Interface for Students Joshua Glatt Making the Transition to Linux: A Guide to the Linux Command Line Interface for Students Joshua Glatt Copyright © 2008 Joshua Glatt Revision History Revision 1.31 14 Sept 2008 jg Various small but useful changes, preparing to revise section on vi Revision 1.30 10 Sept 2008 jg Revised further reading and suggestions, other revisions Revision 1.20 27 Aug 2008 jg Revised first chapter, other revisions Revision 1.10 20 Aug 2008 jg First major revision Revision 1.00 11 Aug 2008 jg First official release (w00t) Revision 0.95 06 Aug 2008 jg Second beta release Revision 0.90 01 Aug 2008 jg First beta release License This document is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 United States License [http:// creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/us/]. Legal Notice This document is distributed in the hope that it will be useful, but it is provided “as is” without express or implied warranty of any kind; without even the implied warranties of merchantability or fitness for a particular purpose. Although the author makes every effort to make this document as complete and as accurate as possible, the author assumes no responsibility for errors or omissions, nor does the author assume any liability whatsoever for incidental or consequential damages in connection with or arising out of the use of the information contained in this document. The author provides links to external websites for informational purposes only and is not responsible for the content of those websites. -

Hands on #1 Overview

Hands On #1 ercises Overview See Wednesday’ s hands on Part Where1 : Starting is your andinstallation familiarizing ? Getting the example programs Running novice examples : N01, N03, N02 … Part Examine2 : Looking cross into sections Geant4, trying it out with ex Simulate depth dose curve Compute and plot Bragg curve Addenda : other examples, histogramming Your Geant4 installation VMware Player users under Windows or Mac OS all files downloaded from http://geant4.in2p3.fr/cenbg/vmware.html in principle, no installation needed all your peripherals should be operational (WiFi, disks,…) Installation from beginning CERN link http://geant4.web.cern.ch/geant4/support/download.shtml SLAC link http://geant4.slac.stanford.edu/installation/ User forum http://geant4-hn.slac.stanford.edu:5090/HyperNews/public/get/installconfig.html Installation guide http://geant4.web.cern.ch/geant4/UserDocumentation/UsersGuides/InstallationGuide/html/index.html This Hands On will help you check your installation of Geant4 is correct If not, we can try to help during this Hands On… Access your Geant4 installation for VMware users Start the VMware player software Start your VMware machine Log onto the VMware machine Username: local1 , password: local1 Open a terminal (right click on desktop with mouse) You are now working under Scientific Linux 4.2 with gcc 3.4.4 By default on your Windows PC, the directory /mnt/hgfs/echanges is a link to C:\ Tips for VMware users (1/2) Geant4 8.3 installation path : /usr/local/geant4 you need root privileges -

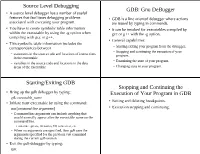

Source Level Debugging GDB: Gnu Debugger Starting/Exiting GDB Stopping and Continuing the Execution of Your Program In

Source Level Debugging GDB: Gnu DeBugger ● A source level debugger has a number of useful features that facilitates debugging problems ● GDB is a line oriented debugger where actions associated with executing your program. are issued by typing in commands. ● You have to create symbolic table information ● It can be invoked for executables compiled by within the executable by using the -g option when gcc or g++ with the -g option. compiling with gcc or g++. ● General capabilities: ● This symbolic table information includes the correspondances between – Starting/exiting your program from the debugger. – Stopping and continuing the execution of your – statements in the source code and locations of instructions program. in the executable – Examining the state of your program. – variables in the source code and locations in the data areas of the executable – Changing state in your program. Starting/Exiting GDB Stopping and Continuing the ● Bring up the gdb debugger by typing: Execution of Your Program in GDB gdb executable_name ● Setting and deleting breakpoints. ● Initiate your executable by using the command: run [command-line arguments] ● Execution stepping and continuing. – Command line arguments can include anything that would normally appear after the executable name on the command line. ● run-time options, filenames, I/O redirection, etc. – When no arguments are specified, then gdb uses the arguments specified for the previous run command during the current gdb session. ● Exit the gdb debugger by typing: quit Setting and Deleting Breakpoints Examples of Setting and Deleting Breakpoints ● Can set a breakpoint to stop: – at a particular source line number or function (gdb) break # sets breakpoint at current line # number – when a specified condition occurs (gdb) break 74 # sets breakpoint at line 74 in the # current file ● General form. -

Appendix B Development Tools

Appendix B Development Tools Problem Statement Although more proprietary packages are available, there are abundant open source packages, giving its users unprecedented flexibility and freedom of choice, that most users can find an application that exactly meets their needs. However, it is also this pool of choices that drive individuals to share a wide range of preferences and biases. As a result, Linux/Open source packages (and softeware in general) is flooded with religious wars over programming languages, editors, licences, etc. Some are worthwhile debates, others are meaningless flamewars. Throughout Appendix B and next chapter, Appendix C, we intend to summarize a few essential tools (from our point of view) that may help readers to know the aspects and how-to of (1) development tools including programming, debugging, and maintaining, and (2) network experiment tools including name-addressing, perimeter probing, traffic-monitoring, benchmarking, simulating/emulating, and finally hacking. Section B.1 guides readers to begin the developing journey with programming tools. A good first step would be writing the first piece of codes using a Visual Improved (vim) text editor. Then compiling it to binary executables with GNU C compiler (gcc), and furthermore offloading some repetitive compiling steps to the make utility. The old 80/20 rule still works on programming where 80% of your codes come from 20% of your efforts leaving 80% of your efforts go buggy about your program. Therefore you would need some debugging tools as dicussed in Section 1.2. including source-level debugging, GNU Debugger (gdb), or a GUI fasion approach, Data Display Debugger (ddd), and debug the kernel itself using remote Kernel GNU Debugger (kgdb). -

![The Data Display Debugger Ddd [−−Gdb] [−−Dbx] [−−Xdb] [−−Jdb]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0462/the-data-display-debugger-ddd-gdb-dbx-xdb-jdb-1680462.webp)

The Data Display Debugger Ddd [−−Gdb] [−−Dbx] [−−Xdb] [−−Jdb]

() () NAME ddd, xddd - the data display debugger SYNOPSIS ddd [ −−gdb ][−−dbx ][−−xdb ][−−jdb ][−−pydb ][−−perl ][−−debugger name ][−−[r]host [username@]hostname ]] [−−help ][−−trace ][−−version ][−−configuration ][options... ] [ program [ core | process-id ]] but usually just ddd program DESCRIPTION The purpose of a debugger such as DDD is to allow you to see what is going on “inside” another program while it executes—or what another program was doing at the moment it crashed. DDD can do four main kinds of things (plus other things in support of these) to help you catch bugs in the act: • Start your program, specifying anything that might affect its behavior. • Make your program stop on specified conditions. • Examine what has happened, when your program has stopped. • Change things in your program, so you can experiment with correcting the effects of one bug and go on to learn about another. “Classical” UNIX debuggers such as the GNU debugger (GDB) provide a command-line interface and a multitude of commands for these and other debugging purposes. DDD is a comfortable graphical user interface around an inferior GDB, DBX, XDB, JDB, Python debugger, or Perl debugger. INVOKING DDD You can run DDD with no arguments or options. However, the most usual way to start DDD is with one argument or two, specifying an executable program as the argument: ddd program You can also start with both an executable program and a core file specified: ddd program core You can, instead, specify a process ID as a second argument, if you want to debug a running process: ddd program 1234 would attach DDD to process 1234 (unless you also have a file named ‘ 1234 ’; DDD does check for a core file first). -

Debugging and Tuning Linux for EDA

Debugging and Tuning Linux for EDA Fabio Somenzi [email protected] University of Colorado at Boulder Outline Compiling gcc icc/ecc Debugging valgrind purify ddd Profiling gcov, gprof quantify vtl valgrind Compiling Compiler options related to static checks debugging optimization Profiling-driven optimization Compiling with GCC gcc -Wall -O3 -g reports most uses of potentially uninitialized variables -O3 (or -O6) necessary to trigger dataflow analysis can be fooled by if (cond) x = VALUE; ... if (cond) y = x; Uninitialized variables not considered for register allocation may escape Achieving -Wall-clean code is not too painful and highly desirable Compiling C code with g++ is more painful, but has its rewards Compiling with GCC gcc -mcpu=pentium4 -malign-double -mcpu=pentium4 optimizes for the Pentium 4, but produces code that runs on any x86 -march=pentium4 uses Pentium 4-specific instructions -malign-double forces alignment of double’s to double-word boundary Use either for all files or for none gcc -mfpmath=sse Controls the use of SSE instructions for floating point For complete listing, check gcc’s info page under Invoking gcc ! Submodel Options Compiling with ICC ICC is the Intel compiler for IA-32 systems. http://www.intel.com/software/products/ icc -O3 -g -ansi -w2 -Wall Aggressive optimization Retain debugging info Strict ANSI conformance Display remarks, warnings, and errors Enable all warnings Remarks tend to be a bit overwhelming Fine grain control over diagnostic: see man page Compiling with ICC icc -tpp7 Optimize instruction scheduling -

The Visual Development of GCC Plug-Ins with GDE

The Visual Development of GCC Plug-ins with GDE Daniel J. Dean Sean Callanah Erez Zadok Stony Brook University Stony Brook University Stony Brook University [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Appears in the Proceedings of the 2009 GCC Developers’ Summit Abstract application-specific custom optimizations, integrated type checking, function call logging, or parallism to Being able to directly affect code compilation with code code at compile time [2] [30] [24] [21]. Code trans- transformations allows the seamless addition of custom formations give developers this ability by modify- optimizations and specialized functionality to code at ing the compiler’s internal representation of compiling compile time. Traditionally, this has only been possi- code. The traditional development of code transforma- ble by directly modifying compiler source code: a very tions,however, requires the direct modification of com- difficult task. Using GCC plug-ins, developers can di- piler source files, a difficult and error prone task. As rectly affect code compilation, without actually modi- Section 3 explains, GNU Compiler Collection (GCC) fying the source code of GCC. While this makes ap- plug-ins are code transformations which do not require plying a completed plug-in easy, plug-in development the developer modify the compiler source itself [6]. Al- is transformation development nonetheless: an arduous though this makes the application and deployment of task. The plug-in developer is required to have the same completed transformations a relatively simple process, thorough understanding of compiler internals, complex plug-in development is an arduous task. compiler internal representations, and non-trivial source to internal representation mappings as any other trans- The GCC developer community has a great deal of ex- formation developer. -

Professional Linux Programming.Pdf

01_776130 ffirs.qxp 2/2/07 10:13 PM Page iii Professional Linux® Programming Jon Masters Richard Blum 01_776130 ffirs.qxp 2/2/07 10:13 PM Page ii 01_776130 ffirs.qxp 2/2/07 10:13 PM Page i Professional Linux® Programming 01_776130 ffirs.qxp 2/2/07 10:13 PM Page ii 01_776130 ffirs.qxp 2/2/07 10:13 PM Page iii Professional Linux® Programming Jon Masters Richard Blum 01_776130 ffirs.qxp 2/2/07 10:13 PM Page iv Professional Linux® Programming Published by Wiley Publishing, Inc. 10475 Crosspoint Boulevard Indianapolis, IN 46256 www.wiley.com Copyright © 2007 by Wiley Publishing, Inc., Indianapolis, Indiana Published simultaneously in Canada Manufactured in the United States of America 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data: Masters, Jon, 1981- Professional Linux programming / Jon Masters, Richard Blum. p. cm. Includes index. ISBN: 978-0-471-77613-0 (paper/website) 1. Linux. 2. Operating systems (Computers) I. Blum, Richard, 1962- II. Title. QA76.76.O63M37153 2007 005.4’32—dc22 2006102202 No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning or otherwise, except as permitted under Sections 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright Act, without either the prior written permission of the Publisher, or authorization through payment of the appropriate per-copy fee to the Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, (978) 750-8400, fax (978) 646-8600. -

ANIMAL-FARM: an Extensible Framework for Algorithm Visualization

ANIMAL-FARM: An Extensible Framework for Algorithm Visualization Vom Fachbereich Elektrotechnik und Informatik der Universitat¨ Siegen zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades Doktor der Ingenieurwissenschaften (Dr.-Ing.) genehmigte Dissertation von Diplom-Informatiker Guido Roßling¨ geboren in Darmstadt 1. Gutachter: Prof. Dr. Bernd Freisleben 2. Gutachter: Prof. Dr. Mira Mezini Tag der mundlichen¨ Prufung:¨ 11. April 2002 ii Acknowledgments The material presented in this thesis is based on my research during my time as a research assistant in the Parallel Systems Research Group at the Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science at the University of Siegen, Germany. I would like to thank all collaboration partners who made this research enjoyable and productive. Apart from many discussion partners at conferences who offered insights or sparked ideas, I want to thank some persons individually. First of all, I want to thank my academic mentor Bernd Freisleben who gave me the freedom needed for developing this thesis. He also supported the incorporation of algorithm visualizations in the Introduction to Computer Science course. Apart from giving hints on academic research techniques and assisting me in writing papers, he has also graciously invested much financial support into the stressful year of 2000, when I was presenting my research status at six conferences. I also wish to thank my second advisor Mira Mezini for her advice in software engineering aspects. Her insights on developing adaptable software systems gave me a starting point for my exploration of dynamically configurable and extensible software. Several members at the department have helped developing ANIMAL-FARM and the ANIMAL sys- tem. Markus Schuler¨ helped to design and implement the first ANIMAL prototype as his Mas- ter’s Thesis. -

Used Tools and Mechanisms in Open Source Projects (A School Seminar Work)

Used tools and mechanisms in Open Source projects (a school seminar work) Heikki Orsila <heikki.orsila@iki.fi> 2007-03-08 This document may be used and distributed under GNU Free Documen- tation (http://www.gnu.org/copyleft/fdl.html) and/or Commons Attribution- Share Alike 2.5 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.5/) license con- ditions. 0-0 1 Outline • Present some common tools and mechanisms used in developing Open Source projects • Focuses on GNU/Linux and UNIX-like operating systems, other oper- ating systems are ignored • Focuses on C language tools, since C is the dominant language used in Open Source operating systems • Presents only Open Source tools • The purpose is to only present most popular tools and most common mechanisms in development • This document was created from following information sources: – Freshmeat: http://freahmeat.net is an excellent source for finding UNIX programs by category, see http://freshmeat.net/browse/18/ 0-1 – Wikipedia – Google – Personal experience ;) – Acquaints from IRCNet ;) 0-2 • Topics of this presentation are: – Section 2: Compilers and linkers – Section 3: Interpreted languages – Section 4: Source code tools – Section 5: Debugging tools – Section 6: Documentation tools – Section 7: Version control tools – Section 8: Text editors – Section 9: Building tools – Section 10: Integrated development environments (IDEs) – Section 11: Reverse engineering tools – Section 12: Compression, cryptography and packaging tools – Section 13: Network tools – Section 14: Emulators 0-3 2 Compilers and linkers • A compiler is the main tool for programming • A compiler translates source code into executable format, possibly opti- mising and verifying the code for correctness • C is the most widely used programming language on UNIX systems and GNU C compiler is the most popular compiler • GNU Compiler Collection (GCC ) provides compilers for Ada, C, C++, Objective-C, Fortran and Java. -

CSE 303 Lecture 13A

CSE 303 Lecture 13a Debugging C programs reading: Programming in C Ch. 13 slides created by Marty Stepp http://www.cs.washington.edu/303/ 1 gdb • gdb : GNU debugger. Helps you step through C programs. absolutely essential for fixing crashes and bad pointer code your program must have been compiled with the -g flag • usage: $ gdb program GNU gdb Fedora (6.8-23.fc9) Copyright (C) 2008 Free Software Foundation, Inc... (gdb) run parameters ... • redirecting input: $ gdb program (gdb) run parameters < inputfile 2 gdb commands command description run or r parameters run the program break or b place sets a breakpoint at the given place: - a function's name - a line number - a source file : line number print or p expression prints the given value / variable step or s advances by one line of code ("step into") next or n advances by one line of code ("step over") finish runs until end of function ("step out") continue or c resumes running program backtrace or bt display current function call stack quit or q exits gdb 3 A gdb session $ gdb intstack GNU gdb 5.2.1 Copyright 2002 Free Software Foundation, Inc. (gdb) b 34 Breakpoint 1 at 0x4010ea: file intstack.c, line 34. (gdb) r Starting program: /home/user/intstack Breakpoint 1, main () at intstack.c:34 34 Node* oldFront = stack; (gdb) p stack $1 = (Node *) 0x4619c0 (gdb) n 35 printf("%d\n", stack->data); (gdb) n 36 stack = stack->next; (gdb) n 37 free(oldFront); (gdb) p stack $4 = (Node *) 0x462856 (gdb) p oldFront $2 = (Node *) 0x4619c0 (gdb) p *oldFront $3 = {data = 10, next = 0x462856} (gdb) c Continuing.