August 26, 2005

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Driving Prosperity Driving Prosperity Through Transport Solutions

VOLVO GROUP ANNUAL AND SUSTAINABILITY REPORT 2018 Driving prosperity Driving prosperity through transport solutions The Volvo Group’s mission statement expresses a broad ambition – to drive prosperity. Our customers provide modern logistics as the base for our economic welfare. Transport supports growth, provides access for people and goods and helps combat poverty. Modern transport solutions facilitate the increasing urbanization in a more sustainableainable way. Transport is not an end in itself, but ratherher a means allowing people to access what theyhey need, economically and socially. A GLOBAL GROUP 2018 OVERVIEW Our customers make societies work The Volvo Group’s products and services contribute to much of what Volvo Group’s customers are companies within the transportation we all expect of a well-functioning society. Our trucks, buses, engines, or infrastructure industries. The reliability and productivity of the construction equipment and financial services are involved in many products are important and in many cases crucial to our customers’ of the functions that most of us rely on every day. The majority of the success and profitability. ON THE ROAD OFF ROAD IN THE CITY AT SEA Our products help ensure that Engines, machines and vehicles Our products are part of daily Our products and services people have food on the table, from the Volvo Group can be life. They take people to work, are there, regardless of whether can travel to their destination found at construction sites, in collect rubbish and keep lights someone is at work on a ship, and have roads to drive on. mines and in the middle of shining. -

Lot S37 / Serial No

THREE IN A ROW A TRIO OF CONSECUTIVE SERIAL NUMBERED WHITE 2-44s TO BE OFFERED IN DAVENPORT BY CHELSEY HINSENKAMP he White tractor brand can trace its deep roots all the story goes, White’s son Rollin found his inspiration in the way back to sewing machines, oddly enough. The his father’s unreliable and headache-inducing steam car, a brand’s long and winding tale begins in 1858 in Templeton, Locomobile. So, just before the turn of the century, Rollin Massachusetts, where entrepreneur Thomas White first founded began working on a design for a steam generator with the the White Manufacturing Company. Determined to see the goal of besting the Locomobile. endeavor succeed, White quickly decided to relocate company Rollin was surprisingly quite successful in his undertaking, headquarters to the more centrally positioned Cleveland, and he soon secured a patent for his final product. He Ohio, and in 1876, the business was officially incorporated attempted to market the steam generator to various as the White Sewing Machine Company—fitting, as sewing automobile builders of the day, including Locomobile, but machines were what the company produced. finding little interest, he instead convinced his father to White achieved his aim at building a successful and sustainable allow him use of some of the sewing machine company’s business, and after two decades at the company’s helm while resources in order to construct a vehicle of his own. raising a family, White welcomed his sons into the business Rollin’s brothers Windsor and Walter were quick to join as they came of age. -

Engine Control Module (ECM), Diagnostic Trouble Code (DTC), Guide 2010 Emissions

Service Information Trucks Group 28 Release2 Engine Control Module (ECM), Diagnostic Trouble Code (DTC), Guide 2010 Emissions 89046912 Foreword The descriptions and service procedures contained in this manual are based on designs and technical studies carried out through January 2012. The products are under continuous development. Vehicles and components produced after the above date may therefore have different specifications and repair methods. When this is deemed to have a significant bearing on this manual, an updated version of this manual will be issued to cover the changes. The new edition of this manual will update the changes. In service procedures where the title incorporates an operation number, this is a reference to an V.S.T. (Volvo Standard Times). Service procedures which do not include an operation number in the title are for general information and no reference is made to an V.S.T. Each section of this manual contains specific safety information and warnings which must be reviewed before performing any procedure. If a printed copy of a procedure is made, be sure to also make a printed copy of the safety information and warnings that relate to that procedure. The following levels of observations, cautions and warnings are used in this Service Documentation: Note: Indicates a procedure, practice, or condition that must be followed in order to have the vehicle or component function in the manner intended. Caution: Indicates an unsafe practice where damage to the product could occur. Warning: Indicates an unsafe practice where personal injury or severe damage to the product could occur. Danger: Indicates an unsafe practice where serious personal injury or death could occur. -

Volvo Grp. N. Am., LLC V. Roberts Truck Ctr., Ltd., 2020 NCBC 28

Volvo Grp. N. Am., LLC v. Roberts Truck Ctr., Ltd., 2020 NCBC 28. STATE OF NORTH CAROLINA IN THE GENERAL COURT OF JUSTICE SUPERIOR COURT DIVISION GUILFORD COUNTY 19 CVS 2981 VOLVO GROUP NORTH AMERICA, LLC d/b/a VOLVO TRUCKS NORTH AMERICA, a Delaware limited liability company; and MACK TRUCKS, INC., a Pennsylvania corporation, Plaintiffs, ORDER AND OPINION ON v. PLAINTIFFS’ MOTIONS FOR JUDGMENT ON THE PLEADINGS ROBERTS TRUCK CENTER, LTD., a AND TO DISMISS DEFENDANTS’ Texas limited partnership; ROBERTS COUNTERCLAIMS TRUCK CENTER OF KANSAS, LLC, a Kansas limited liability company; and ROBERTS TRUCK CENTER HOLDING COMPANY, LLC, a Texas limited liability company, Defendants. 1. THIS MATTER is before the Court on Plaintiffs Volvo Group North America, LLC d/b/a Volvo Trucks North America’s (“Volvo”) and Mack Trucks, Inc.’s (“Mack”) separate motions for judgment on the pleadings, and Plaintiffs’ joint Motion to Dismiss Defendants’ Counterclaims (collectively the “Motions”). After considering the Motions, the briefs in support of and in opposition to the Motions, and the arguments of counsel at a hearing held on September 5, 2019, for the reasons discussed below, the Court GRANTS Mack’s Motion for Judgment on the Pleadings and Motion to Dismiss Defendants’ Counterclaims, DENIES Volvo’s Motion for Judgment on the Pleadings, GRANTS in part and DENIES in part Volvo’s Motion to Dismiss Defendants’ Counterclaims, and severs for early determination the dispute regarding the applicable 2017 Volvo sales quota (the “Severed Issue”). The Court DEFERS further proceedings until the Severed Issue is determined. Kilpatrick Townsend & Stockton LLP, by Chad D. -

Motor Vehicle Make Abbreviation List Updated As of June 21, 2012 MAKE Manufacturer AC a C AMF a M F ABAR Abarth COBR AC Cobra SKMD Academy Mobile Homes (Mfd

Motor Vehicle Make Abbreviation List Updated as of June 21, 2012 MAKE Manufacturer AC A C AMF A M F ABAR Abarth COBR AC Cobra SKMD Academy Mobile Homes (Mfd. by Skyline Motorized Div.) ACAD Acadian ACUR Acura ADET Adette AMIN ADVANCE MIXER ADVS ADVANCED VEHICLE SYSTEMS ADVE ADVENTURE WHEELS MOTOR HOME AERA Aerocar AETA Aeta DAFD AF ARIE Airel AIRO AIR-O MOTOR HOME AIRS AIRSTREAM, INC AJS AJS AJW AJW ALAS ALASKAN CAMPER ALEX Alexander-Reynolds Corp. ALFL ALFA LEISURE, INC ALFA Alfa Romero ALSE ALL SEASONS MOTOR HOME ALLS All State ALLA Allard ALLE ALLEGRO MOTOR HOME ALCI Allen Coachworks, Inc. ALNZ ALLIANZ SWEEPERS ALED Allied ALLL Allied Leisure, Inc. ALTK ALLIED TANK ALLF Allison's Fiberglass mfg., Inc. ALMA Alma ALOH ALOHA-TRAILER CO ALOU Alouette ALPH Alpha ALPI Alpine ALSP Alsport/ Steen ALTA Alta ALVI Alvis AMGN AM GENERAL CORP AMGN AM General Corp. AMBA Ambassador AMEN Amen AMCC AMERICAN CLIPPER CORP AMCR AMERICAN CRUISER MOTOR HOME Motor Vehicle Make Abbreviation List Updated as of June 21, 2012 AEAG American Eagle AMEL AMERICAN ECONOMOBILE HILIF AMEV AMERICAN ELECTRIC VEHICLE LAFR AMERICAN LA FRANCE AMI American Microcar, Inc. AMER American Motors AMER AMERICAN MOTORS GENERAL BUS AMER AMERICAN MOTORS JEEP AMPT AMERICAN TRANSPORTATION AMRR AMERITRANS BY TMC GROUP, INC AMME Ammex AMPH Amphicar AMPT Amphicat AMTC AMTRAN CORP FANF ANC MOTOR HOME TRUCK ANGL Angel API API APOL APOLLO HOMES APRI APRILIA NEWM AR CORP. ARCA Arctic Cat ARGO Argonaut State Limousine ARGS ARGOSY TRAVEL TRAILER AGYL Argyle ARIT Arista ARIS ARISTOCRAT MOTOR HOME ARMR ARMOR MOBILE SYSTEMS, INC ARMS Armstrong Siddeley ARNO Arnolt-Bristol ARRO ARROW ARTI Artie ASA ASA ARSC Ascort ASHL Ashley ASPS Aspes ASVE Assembled Vehicle ASTO Aston Martin ASUN Asuna CAT CATERPILLAR TRACTOR CO ATK ATK America, Inc. -

Car Owner's Manual Collection

Car Owner’s Manual Collection Business, Science, and Technology Department Enoch Pratt Free Library Central Library/State Library Resource Center 400 Cathedral St. Baltimore, MD 21201 (410) 396-5317 The following pages list the collection of old car owner’s manuals kept in the Business, Science, and Technology Department. While the manuals cover the years 1913-1986, the bulk of the collection represents cars from the 1920s, ‘30s, and 40s. If you are interested in looking at these manuals, please ask a librarian in the Department or e-mail us. The manuals are noncirculating, but we can make copies of specific parts for you. Auburn……………………………………………………………..……………………..2 Buick………………………………………………………………..…………………….2 Cadillac…………………………………………………………………..……………….3 Chandler………………………………………………………………….…...………....5 Chevrolet……………………………………………………………………………...….5 Chrysler…………………………………………………………………………….…….7 DeSoto…………………………………………………………………………………...7 Diamond T……………………………………………………………………………….8 Dodge…………………………………………………………………………………….8 Ford………………………………………………………………………………….……9 Franklin………………………………………………………………………………….11 Graham……………………………………………………………………………..…..12 GM………………………………………………………………………………………13 Hudson………………………………………………………………………..………..13 Hupmobile…………………………………………………………………..………….17 Jordan………………………………………………………………………………..…17 LaSalle………………………………………………………………………..………...18 Nash……………………………………………………………………………..……...19 Oldsmobile……………………………………………………………………..……….21 Pontiac……………………………………………………………………….…………25 Packard………………………………………………………………….……………...30 Pak-Age-Car…………………………………………………………………………...30 -

Copyricht, 1914, by Kanaaa Farmer Co

CopyriCht, 1914, by Kanaaa Farmer Co. Septe!Dber 12, 1014 KANSAS FARME'P 1111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111"1,,.1111,111111111111111111111111IIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIII� OIIIII1II1II1IUIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIII1111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111 ,IIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIJIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIII111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111", � IIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIUIIIIII'IIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIII1IIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIII,IIIIIIIIIIII(llll1�"111I11I11I11I11I11I11I11I11I11I1IIIIIIIII,... iii .'1111111 Brothers .soua if son' , \ il;;;; Apper iii Home:-'Ma'de Automo.bil es IIiii �ii iii iii == 'know what to in a "home-made" pie. �� You expect -- ii new a ii Let us tell what we mean when we call the Apperson iii you ii 41home-mad� automobile." ii • ii lir.t I • car, "anel Apper.ota, Americd. , ,�� A bjt',:':Etnl��" Edgar -- ·de.igned: ii / own our motor car builder.-+95%···of tlie part. made in our factory, by �� -- of ii own men-the entire car con.tructed under the per.onal mpervi.ion �i ii Brother•• ii the Apper.on == �! -- because , what into the· finished car, ii Thus we know just exactly goes �! -- we make the- ii ii ii Fenders ii Motors Steering Gears Drop Forgings �� Brake Rods and Cushions -- Transmissions Famous Apperson ii Sweet-Metal iii Axles Clutch Control Rods All ii Rear ii Parts == Radiators '. Froitt Axles �� Bra�es -

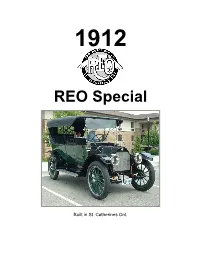

REO and the Canadian Connection

1912 REO Special Built in St. Catherines Ont. Specifications 1912 REO Body style 5 passenger touring car Engine 4 cylinder "F-Head" 30-35 horsepower Bore & Stroke: 4 inch X 4 ½ inches (10 cm X 11.5 cm) Ignition Magneto Transmission 3 speeds + reverse Clutch Multiple disk Top speed 38 miles per hour (60 k.p.h.) Wheelbase 112 inches (2.8 metres) Wheels 34 inch (85 cm) demountable rims 34 X 4 inch tires (85 cm X 10 cm) Brakes 2 wheel, on rear only 14 inch (35 cm) drums Lights Headlights - acetylene Side and rear lamps - kerosene Fuel system Gasoline, 14 gallon (60 litre) tank under right seat gravity flow system Weight 3000 pounds (1392 kg) Price $1055 (U.S. model) $1500 (Canadian model) Accessories Top, curtains, top cover, windshield, acetylene gas tank, and speedometer ... $100 Self-starter ... $25 Features Left side steering wheel center control gear shift Factories Lansing, Michigan St. Catharines, Ontario REO History National Park Service US Department of the Interior In 1885, Ransom became a partner in his father's machine shop firm, which soon became a leading manufacturer of gas-heated steam engines. Ransom developed an interest in self- propelled land vehicles, and he experimented with steam-powered vehicles in the late 1880s. In 1896 he built his first gasoline car and one year later he formed the Olds Motor Vehicle Company to manufacture them. At the same time, he took over his father's company and renamed it the Olds Gasoline Engine Works. Although Olds' engine company prospered, his motor vehicle operation did not, chiefly because of inadequate capitalization. -

Annual and Sustainability Report 2017 Driving Performance

THE VOLVO GROUP Annual and Sustainability Report 2017 Driving Performance The Volvo Group 2017 The Volvo and Innovation WorldReginfo - 3016dca3-d4db-498b-9818-3a9e015e9095 CONTENT A GLOBAL GROUP STRONG BRANDS OVERVIEW This is the Volvo Group. 2 CEO comments. 4 he Volvo Group’s brand port- folio consists of Volvo, Volvo STRATEGY T Committed to staying ahead . 8 Penta, UD, Terex Trucks, Renault Mission. 10 Trucks, Prevost, Nova Bus and Vision. .10 Mack. We partner in alliances and Values . 10 joint ventures with the SDLG, Aspirations. .11 Code of Conduct . 11 Eicher and Dongfeng brands. By Driving innovation. 12 offering products and services Strategic priorities. 16 under different brands, the Group Financial targets. .21 addresses many different BUSINESS MODEL customer and market segments in VALUE CHAIN. 24 mature as well as growth markets. Customers . 28 Product development . 34 Purchasing. 46 Production & Logistics . 48 Retail & Service . 54 Reuse. 60 EMPLOYEES . 68 OUR ROLE IN SOCIETY. 74 GROUP PERFORMANCE BOARD OF DIRECTORS’ REPORT 2017 Sustainability Reporting Index . 82 Global strength in a changing world. 82 Significant events. 84 Financial performance . 86 Financial position . 89 Cash flow statement . 92 Trucks . 94 Construction Equipment . 98 Buses. 101 Volvo Penta . 103 Financial Services. 105 Financial management . 107 Changes in consolidated shareholders’ equity. 108 The share. 109 Risks and uncertainties. 112 NOTES Notes to the financial statements. 118 Parent Company AB Volvo . 178 CORPORATE GOVERNANCE Corporate Governance Report 2017 . 188 Board of Directors. 196 Group Executive Board. 202 OTHER INFORMATION Proposed remuneration policy. .206 Proposed disposition of unappropriated earnings . 207 Audit report for AB Volvo (publ) . -

Volvo Products for Transportation Management Wireless Roadside Inspection Concepts Pilot Project in the Port of Gothenburg

Jan Hellaker Vice President, Volvo Technology North America Volvo Technology A few samples of Volvo’s experience from applying ITS to goods transportation Volvo products for Transportation Management Wireless Roadside Inspection concepts Pilot project in the Port of Gothenburg Volvo Technology Business AreasAreas Volvo Trucks Renault Trucks Mack Trucks Nissan Diesel The world’s 2nd largest manufacturer of heavy trucks Construction Buses Equipment VolvoMack Trucks Penta Volvo Aero Financial Services Volvo Technology Sales and Employees Worldwide 2008 EUROPE Sales 52% NORTH AMERICA 61,130 60% Sales 16% 14,200 14% ASIA Sales 19% 19,090 19% SOUTH AMERICA Sales 7% 4,380 4% OTHER Sales 7% 2,580 3% Volvo Technology Corporate Values Volvo Technology Connected Truck Authorities Fleet operators Road charging, emission control, dangerous Improved transport efficiency and goods monitoring, e-call (e-safety), cost optimization, driver time anti-theft solutions etc. management, cargo management & security/safety Drivers & families Keeping touch with messaging Finance/insurance companies Focus on minimizing Cargo owner risk by monitoring & control – security Monitoring of location, & status etc. & usage 3rd party service & Truck manufacturers/dealer software companies In order to manage up-time, increase parts & service sales Integration of 3rd party solutions and improve customer relationship management Volvo Technology DYNAFLEET Volvo´s online transport information system Volvo Technology Product history ’09- VolvoLink ’08- VTNA ’06- Optifleet RT DF -

Electric and Hybrid Cars SECOND EDITION This Page Intentionally Left Blank Electric and Hybrid Cars a History

Electric and Hybrid Cars SECOND EDITION This page intentionally left blank Electric and Hybrid Cars A History Second Edition CURTIS D. ANDERSON and JUDY ANDERSON McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers Jefferson, North Carolina, and London LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGUING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA Anderson, Curtis D. (Curtis Darrel), 1947– Electric and hybrid cars : a history / Curtis D. Anderson and Judy Anderson.—2nd ed. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-7864-3301-8 softcover : 50# alkaline paper 1. Electric automobiles. 2. Hybrid electric cars. I. Anderson, Judy, 1946– II. Title. TL220.A53 2010 629.22'93—dc22 2010004216 British Library cataloguing data are available ©2010 Curtis D. Anderson. All rights reserved No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying or recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. On the cover: (clockwise from top left) Cutaway of hybrid vehicle (©20¡0 Scott Maxwell/LuMaxArt); ¡892 William Morrison Electric Wagon; 20¡0 Honda Insight; diagram of controller circuits of a recharging motor, ¡900 Manufactured in the United States of America McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers Box 611, Je›erson, North Carolina 28640 www.mcfarlandpub.com To my family, in gratitude for making car trips such a happy time. (J.A.A.) This page intentionally left blank TABLE OF CONTENTS Acronyms and Initialisms ix Preface 1 Introduction: The Birth of the Automobile Industry 3 1. The Evolution of the Electric Vehicle 21 2. Politics 60 3. Environment 106 4. Technology 138 5. -

The Tupelo Automobile Museum Auction Tupelo, Mississippi | April 26 & 27, 2019

The Tupelo Automobile Museum Auction Tupelo, Mississippi | April 26 & 27, 2019 The Tupelo Automobile Museum Auction Tupelo, Mississippi | Friday April 26 and Saturday April 27, 2019 10am BONHAMS INQUIRIES BIDS 580 Madison Avenue Rupert Banner +1 (212) 644 9001 New York, New York 10022 +1 (917) 340 9652 +1 (212) 644 9009 (fax) [email protected] [email protected] 7601 W. Sunset Boulevard Los Angeles, California 90046 Evan Ide From April 23 to 29, to reach us at +1 (917) 340 4657 the Tupelo Automobile Museum: 220 San Bruno Avenue [email protected] +1 (212) 461 6514 San Francisco, California 94103 +1 (212) 644 9009 John Neville +1 (917) 206 1625 bonhams.com/tupelo To bid via the internet please visit [email protected] bonhams.com/tupelo PREVIEW & AUCTION LOCATION Eric Minoff The Tupelo Automobile Museum +1 (917) 206-1630 Please see pages 4 to 5 and 223 to 225 for 1 Otis Boulevard [email protected] bidder information including Conditions Tupelo, Mississippi 38804 of Sale, after-sale collection and shipment. Automobilia PREVIEW Toby Wilson AUTOMATED RESULTS SERVICE Thursday April 25 9am - 5pm +44 (0) 8700 273 619 +1 (800) 223 2854 Friday April 26 [email protected] Automobilia 9am - 10am FRONT COVER Motorcars 9am - 6pm General Information Lot 450 Saturday April 27 Gregory Coe Motorcars 9am - 10am +1 (212) 461 6514 BACK COVER [email protected] Lot 465 AUCTION TIMES Friday April 26 Automobilia 10am Gordan Mandich +1 (323) 436 5412 Saturday April 27 Motorcars 10am [email protected] 25593 AUCTION NUMBER: Vehicle Documents Automobilia Lots 1 – 331 Stanley Tam Motorcars Lots 401 – 573 +1 (415) 503 3322 +1 (415) 391 4040 Fax ADMISSION TO PREVIEW AND AUCTION [email protected] Bonhams’ admission fees are listed in the Buyer information section of this catalog on pages 4 and 5.