Structural Change and Product Differentiation in the Heavy-Truck

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lot S37 / Serial No

THREE IN A ROW A TRIO OF CONSECUTIVE SERIAL NUMBERED WHITE 2-44s TO BE OFFERED IN DAVENPORT BY CHELSEY HINSENKAMP he White tractor brand can trace its deep roots all the story goes, White’s son Rollin found his inspiration in the way back to sewing machines, oddly enough. The his father’s unreliable and headache-inducing steam car, a brand’s long and winding tale begins in 1858 in Templeton, Locomobile. So, just before the turn of the century, Rollin Massachusetts, where entrepreneur Thomas White first founded began working on a design for a steam generator with the the White Manufacturing Company. Determined to see the goal of besting the Locomobile. endeavor succeed, White quickly decided to relocate company Rollin was surprisingly quite successful in his undertaking, headquarters to the more centrally positioned Cleveland, and he soon secured a patent for his final product. He Ohio, and in 1876, the business was officially incorporated attempted to market the steam generator to various as the White Sewing Machine Company—fitting, as sewing automobile builders of the day, including Locomobile, but machines were what the company produced. finding little interest, he instead convinced his father to White achieved his aim at building a successful and sustainable allow him use of some of the sewing machine company’s business, and after two decades at the company’s helm while resources in order to construct a vehicle of his own. raising a family, White welcomed his sons into the business Rollin’s brothers Windsor and Walter were quick to join as they came of age. -

Motor Vehicle Make Abbreviation List Updated As of June 21, 2012 MAKE Manufacturer AC a C AMF a M F ABAR Abarth COBR AC Cobra SKMD Academy Mobile Homes (Mfd

Motor Vehicle Make Abbreviation List Updated as of June 21, 2012 MAKE Manufacturer AC A C AMF A M F ABAR Abarth COBR AC Cobra SKMD Academy Mobile Homes (Mfd. by Skyline Motorized Div.) ACAD Acadian ACUR Acura ADET Adette AMIN ADVANCE MIXER ADVS ADVANCED VEHICLE SYSTEMS ADVE ADVENTURE WHEELS MOTOR HOME AERA Aerocar AETA Aeta DAFD AF ARIE Airel AIRO AIR-O MOTOR HOME AIRS AIRSTREAM, INC AJS AJS AJW AJW ALAS ALASKAN CAMPER ALEX Alexander-Reynolds Corp. ALFL ALFA LEISURE, INC ALFA Alfa Romero ALSE ALL SEASONS MOTOR HOME ALLS All State ALLA Allard ALLE ALLEGRO MOTOR HOME ALCI Allen Coachworks, Inc. ALNZ ALLIANZ SWEEPERS ALED Allied ALLL Allied Leisure, Inc. ALTK ALLIED TANK ALLF Allison's Fiberglass mfg., Inc. ALMA Alma ALOH ALOHA-TRAILER CO ALOU Alouette ALPH Alpha ALPI Alpine ALSP Alsport/ Steen ALTA Alta ALVI Alvis AMGN AM GENERAL CORP AMGN AM General Corp. AMBA Ambassador AMEN Amen AMCC AMERICAN CLIPPER CORP AMCR AMERICAN CRUISER MOTOR HOME Motor Vehicle Make Abbreviation List Updated as of June 21, 2012 AEAG American Eagle AMEL AMERICAN ECONOMOBILE HILIF AMEV AMERICAN ELECTRIC VEHICLE LAFR AMERICAN LA FRANCE AMI American Microcar, Inc. AMER American Motors AMER AMERICAN MOTORS GENERAL BUS AMER AMERICAN MOTORS JEEP AMPT AMERICAN TRANSPORTATION AMRR AMERITRANS BY TMC GROUP, INC AMME Ammex AMPH Amphicar AMPT Amphicat AMTC AMTRAN CORP FANF ANC MOTOR HOME TRUCK ANGL Angel API API APOL APOLLO HOMES APRI APRILIA NEWM AR CORP. ARCA Arctic Cat ARGO Argonaut State Limousine ARGS ARGOSY TRAVEL TRAILER AGYL Argyle ARIT Arista ARIS ARISTOCRAT MOTOR HOME ARMR ARMOR MOBILE SYSTEMS, INC ARMS Armstrong Siddeley ARNO Arnolt-Bristol ARRO ARROW ARTI Artie ASA ASA ARSC Ascort ASHL Ashley ASPS Aspes ASVE Assembled Vehicle ASTO Aston Martin ASUN Asuna CAT CATERPILLAR TRACTOR CO ATK ATK America, Inc. -

Car Owner's Manual Collection

Car Owner’s Manual Collection Business, Science, and Technology Department Enoch Pratt Free Library Central Library/State Library Resource Center 400 Cathedral St. Baltimore, MD 21201 (410) 396-5317 The following pages list the collection of old car owner’s manuals kept in the Business, Science, and Technology Department. While the manuals cover the years 1913-1986, the bulk of the collection represents cars from the 1920s, ‘30s, and 40s. If you are interested in looking at these manuals, please ask a librarian in the Department or e-mail us. The manuals are noncirculating, but we can make copies of specific parts for you. Auburn……………………………………………………………..……………………..2 Buick………………………………………………………………..…………………….2 Cadillac…………………………………………………………………..……………….3 Chandler………………………………………………………………….…...………....5 Chevrolet……………………………………………………………………………...….5 Chrysler…………………………………………………………………………….…….7 DeSoto…………………………………………………………………………………...7 Diamond T……………………………………………………………………………….8 Dodge…………………………………………………………………………………….8 Ford………………………………………………………………………………….……9 Franklin………………………………………………………………………………….11 Graham……………………………………………………………………………..…..12 GM………………………………………………………………………………………13 Hudson………………………………………………………………………..………..13 Hupmobile…………………………………………………………………..………….17 Jordan………………………………………………………………………………..…17 LaSalle………………………………………………………………………..………...18 Nash……………………………………………………………………………..……...19 Oldsmobile……………………………………………………………………..……….21 Pontiac……………………………………………………………………….…………25 Packard………………………………………………………………….……………...30 Pak-Age-Car…………………………………………………………………………...30 -

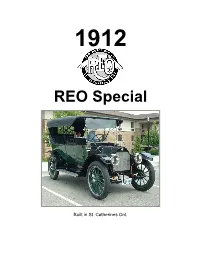

REO and the Canadian Connection

1912 REO Special Built in St. Catherines Ont. Specifications 1912 REO Body style 5 passenger touring car Engine 4 cylinder "F-Head" 30-35 horsepower Bore & Stroke: 4 inch X 4 ½ inches (10 cm X 11.5 cm) Ignition Magneto Transmission 3 speeds + reverse Clutch Multiple disk Top speed 38 miles per hour (60 k.p.h.) Wheelbase 112 inches (2.8 metres) Wheels 34 inch (85 cm) demountable rims 34 X 4 inch tires (85 cm X 10 cm) Brakes 2 wheel, on rear only 14 inch (35 cm) drums Lights Headlights - acetylene Side and rear lamps - kerosene Fuel system Gasoline, 14 gallon (60 litre) tank under right seat gravity flow system Weight 3000 pounds (1392 kg) Price $1055 (U.S. model) $1500 (Canadian model) Accessories Top, curtains, top cover, windshield, acetylene gas tank, and speedometer ... $100 Self-starter ... $25 Features Left side steering wheel center control gear shift Factories Lansing, Michigan St. Catharines, Ontario REO History National Park Service US Department of the Interior In 1885, Ransom became a partner in his father's machine shop firm, which soon became a leading manufacturer of gas-heated steam engines. Ransom developed an interest in self- propelled land vehicles, and he experimented with steam-powered vehicles in the late 1880s. In 1896 he built his first gasoline car and one year later he formed the Olds Motor Vehicle Company to manufacture them. At the same time, he took over his father's company and renamed it the Olds Gasoline Engine Works. Although Olds' engine company prospered, his motor vehicle operation did not, chiefly because of inadequate capitalization. -

UNITED CHURCH of CHRIST, INC. SCHEDULE of INVESTMENTS March 31, 2021 Unaudited - for Information Purposes Only

THE PENSION BOARDS - UNITED CHURCH OF CHRIST, INC. SCHEDULE OF INVESTMENTS March 31, 2021 Unaudited - for information purposes only. SUMMARY OF INVESTMENTS COST VALUE STABLE VALUE INVESTMENTS Short-Term Investments $ 32,253,645 $ 32,253,645 Synthetic Guaranteed Investment Contracts Liquidity Strategy 22,775,770 22,775,770 Total Return Strategy 113,816,896 113,816,896 TOTAL STABLE VALUE INVESTMENTS $ 168,846,312 $ 168,846,312 SHORT-TERM INVESTMENTS Short-term Investments $ 99,844,082 $ 99,844,082 TOTAL SHORT-TERM INVESTMENTS $ 99,844,082 $ 99,844,082 FIXED-INCOME INVESTMENTS Bonds $ 1,100,460,107 $ 1,102,627,965 Bond funds 127,197,863 136,853,018 Asset-backed & Mortgage-backed Securities 252,260,633 255,492,647 TOTAL FIXED-INCOME INVESTMENTS $ 1,479,918,603 $ 1,494,973,630 EQUITY INVESTMENTS Common stocks and equivalents $ 948,021,079 $ 1,367,282,966 Equity funds 295,450,197 366,566,153 TOTAL EQUITY INVESTMENTS $ 1,243,471,276 $ 1,733,849,120 OTHER INVESTMENTS Hedge funds $ 92,035,561 $ 122,358,507 Real assets 107,927,936 98,977,251 Participation in the United Church Funds, Inc. 34,869,973 45,987,425 TOTAL OTHER INVESTMENTS $ 234,833,470 $ 267,323,183 TOTAL INVESTMENTS $ 3,226,913,743 $ 3,764,836,327 PRINCIPAL INTEREST DESCRIPTION SERIES MATURITY COST VALUE AMOUNT RATE % SHORT-TERM INVESTMENTS MFB NI Treasury Money Market Fund $ 32,253,645 $ 32,253,645 TOTAL SHORT-TERM INVESTMENT $ 32,253,645 $ 32,253,645 SYNTHETIC GUARANTEED INVESTMENT CONTRACTS- LIQUIDITY STRATEGY: Asset-Backed Securities 801,908 AEP Texas Inc. -

The Tupelo Automobile Museum Auction Tupelo, Mississippi | April 26 & 27, 2019

The Tupelo Automobile Museum Auction Tupelo, Mississippi | April 26 & 27, 2019 The Tupelo Automobile Museum Auction Tupelo, Mississippi | Friday April 26 and Saturday April 27, 2019 10am BONHAMS INQUIRIES BIDS 580 Madison Avenue Rupert Banner +1 (212) 644 9001 New York, New York 10022 +1 (917) 340 9652 +1 (212) 644 9009 (fax) [email protected] [email protected] 7601 W. Sunset Boulevard Los Angeles, California 90046 Evan Ide From April 23 to 29, to reach us at +1 (917) 340 4657 the Tupelo Automobile Museum: 220 San Bruno Avenue [email protected] +1 (212) 461 6514 San Francisco, California 94103 +1 (212) 644 9009 John Neville +1 (917) 206 1625 bonhams.com/tupelo To bid via the internet please visit [email protected] bonhams.com/tupelo PREVIEW & AUCTION LOCATION Eric Minoff The Tupelo Automobile Museum +1 (917) 206-1630 Please see pages 4 to 5 and 223 to 225 for 1 Otis Boulevard [email protected] bidder information including Conditions Tupelo, Mississippi 38804 of Sale, after-sale collection and shipment. Automobilia PREVIEW Toby Wilson AUTOMATED RESULTS SERVICE Thursday April 25 9am - 5pm +44 (0) 8700 273 619 +1 (800) 223 2854 Friday April 26 [email protected] Automobilia 9am - 10am FRONT COVER Motorcars 9am - 6pm General Information Lot 450 Saturday April 27 Gregory Coe Motorcars 9am - 10am +1 (212) 461 6514 BACK COVER [email protected] Lot 465 AUCTION TIMES Friday April 26 Automobilia 10am Gordan Mandich +1 (323) 436 5412 Saturday April 27 Motorcars 10am [email protected] 25593 AUCTION NUMBER: Vehicle Documents Automobilia Lots 1 – 331 Stanley Tam Motorcars Lots 401 – 573 +1 (415) 503 3322 +1 (415) 391 4040 Fax ADMISSION TO PREVIEW AND AUCTION [email protected] Bonhams’ admission fees are listed in the Buyer information section of this catalog on pages 4 and 5. -

QMC US ARMY Hystory Following the End of World War One in 1919, The

QMC US ARMY Hystory Following the end of World War One in 1919, the U.S. military was demobilized. With numerous states requesting surplus military trucks for road work, Congress sold over 90,000 trucks at bargain prices, leaving the U.S. Army with less than 30,000 trucks by 1921. The U.S. Army was facing a serious problem. The trucks that Congress allowed them to retain were wearing out quickly, and no funding was being authorized to purchase new units. And importantly in the Army’s mind, most of their remaining trucks were essentially 4x2 MILCOTS (military commercial off-the-shelf), trucks that had no tactical cross-country capability. An effort had been made to update World War One Standard B “Liberty” trucks to a more modern “3rd series” specification, but they remained obsolete in design and the conversion rate was too low. In 1920, the U.S. Army Quartermaster Depot at Fort Holabird, Maryland began assembling cross-country vehicles and evaluating their performance. For the most part, components from existing vehicles were used. At Fort Holabird, Army Captain and Chief Engineer Arthur W. Herrington realized that his people could develop and produce purpose-designed high performing cross-country trucks at substantially lower costs than what the automakers were charging the Army for their commercial trucks. Though the automakers were anxious to profit from Army truck sales, few were building a suitable modern truck with all-wheel drive, particularly in the Army’s high volume one to three ton range. In 1928, U.S. Army automotive engineers at Fort Holabird began work on prototypes that would lead to a range of trucks from a 1-1/4 ton 4x4 to a 12 ton 6x6. -

A Trio of Stunning Stutz Automobiles Owned By: Fountainhead Antique Automobile Museum Pacific Northwest Region - CCCA

Winter 2015 1918 Stutz Bulldog A Trio of Stunning Stutz Automobiles Owned by: Fountainhead Antique Automobile Museum Pacific Northwest Region - CCCA PNR-CCCA and Regional Events 2016 CCCA National Events Details can be obtained by contacting the Event Annual Meeting Manager. If no event manager is listed, contact the sponsoring organization. January 14-17 ...................Novi, MI Grand Classics® January 23rd - 30th -- Arizona Concours February 21 ...........Southern Florida Region PNR Contact: Val Dickison March 11 - 13 ..........San Diego/Palm Springs April 9th -- Coming-Out Party June 3 - 5 ...........CCCA Museum Experience PNR Contacts: Gary Johnson, Bill Deibel, Stan Dickison CARavans May 1st -- HCCA Tour April 23 - May 1 ........... North Texas Region September 9-17 ...........New England Region May 7th -- South Prairie Fly-In PNR Contact: Bill Allard May 14th -- Picnic at Sommerville's Director's Message The Last Rohrback Director Comments! PNR Contact: Dennis Somerville 2015 is now in the June 19th -- Father's Day Classics at the Locks bag and I think it was a great year for car July 4th -- Yarrow Point 4th of July Parade events big and small. I PNR Contact: Al McEwan really have a lot of fun tooling around in my August 8th -- Motoring Classic Kick-Off Classic and enjoying at Peter Hageman's Firehouse the company of the finest people in the world. Our club is simply awesome and I have had the opportunity to September 3rd -- Crescent Beach Concours be directly involved with a couple of Grand Classics, a PNR Contacts: Laurel & Colin Gurnsey series of Concours events, two Coming Out Parties (My Favorite: thank you, Gary Johnson), and all the diverse September 9th -- Tour du Jour activities that have been planned by Managers and other Contact: America's Car Museum members. -

Investment Holdings As of June 30, 2019

Investment Holdings As of June 30, 2019 Montana Board of Investments | Portfolio as of June 30, 2019 Transparency of the Montana Investment Holdings The Montana Board of Investment’s holdings file is a comprehensive listing of all manager funds, separately managed and commingled, and aggregated security positions. Securities are organized across common categories: Pension Pool, Asset Class, Manager Fund, Aggregated Individual Holdings, and Non-Pension Pools. Market values shown are in U.S. dollars. The market values shown in this document are for the individual investment holdings only and do not include any information on accounts for receivables or payables. Aggregated Individual Holdings represent securities held at our custodian bank and individual commingled accounts. The Investment Holdings Report is unaudited and may be subject to change. The audited Unified Investment Program Financial Statements, prepared on a June 30th fiscal year-end basis, will be made available once the Legislative Audit Division issues the Audit Opinion. Once issued, the Legislative Audit Division will have the Audit Opinion available online at https://www.leg.mt.gov/publications/audit/agency-search-report and the complete audited financial statements will also be available on the Board’s website http://investmentmt.com/AnnualReportsAudits. Additional information can be found at www.investmentmt.com Montana Board of Investments | Portfolio as of June 30, 2019 2 Table of Contents Consolidated Asset Pension Pool (CAPP) 4 CAPP - Domestic Equities 5 CAPP - International -

Vehicle Make, Vehicle Model

V8, V9 VEHICLE MAKE, VEHICLE MODEL Format: VEHICLE MAKE – 2 numeric VEHICLE MODEL – 3 numeric Element Values: MAKE: Blanks 01-03, 06-10, 12-14, 18-25, 29-65, 69-77, 80-89, 90-94, 98-99 MODEL: Blanks 001-999 Remarks: SEE REMARKS UNDER VEHICLE IDENTIFICATION NUMBER – V12 2009 181 ALPHABETICAL LISTING OF MAKES FARS MAKE MAKE/ NCIC FARS MAKE MAKE/ NCIC MAKE MODEL CODE* MAKE MODEL CODE* CODE TABLE CODE TABLE PAGE # PAGE # 54 Acura 187 (ACUR) 71 Ducati 253 (DUCA) 31 Alfa Romeo 187 (ALFA) 10 Eagle 205 (EGIL) 03 AM General 188 (AMGN) 91 Eagle Coach 267 01 American Motors 189 (AMER) 29-398 Excaliber 250 (EXCL) 69-031 Aston Martin 250 (ASTO) 69-035 Ferrari 251 (FERR) 32 Audi 190 (AUDI) 36 Fiat 205 (FIAT) 33 Austin/Austin 191 (AUST) 12 Ford 206 (FORD) Healey 82 Freightliner 259 (FRHT) 29-001 Avanti 250 (AVTI) 83 FWD 260 (FWD) 98-802 Auto-Union-DKW 269 (AUTU) 69-398 Gazelle 252 (GZL) 69-042 Bentley 251 (BENT) 92 Gillig 268 69-052 Bertone 251 (BERO) 23 GMC 210 (GMC) 90 Bluebird 267 (BLUI) 25 Grumman 212 (GRUM) 34 BMW 191 (BMW) 72 Harley- 253 (HD) 69-032 Bricklin 250 (BRIC) Davidson 80 Brockway 257 (BROC) 69-036 Hillman 251 (HILL) 70 BSA 253 (BSA) 98-806 Hino 270 (HINO) 18 Buick 193 (BUIC) 37 Honda 213 (HOND) 19 Cadillac 194 (CADI) 29-398 Hudson 250 (HUDS) 98-903 Carpenter 270 55 Hyundai 215 (HYUN) 29-002 Checker 250 (CHEC) 08 Imperial 216 (CHRY) 20 Chevrolet 195 (CHEV) 58 Infiniti 216 (INFI) 06 Chrysler 199 (CHRY) 84 International 261 (INTL) 69-033 Citroen 250 (CITR) Harvester 98-904 Collins Bus 270 38 Isuzu 217 (ISU ) 64 Daewoo 201 (DAEW) 88 Iveco/Magirus -

Statements of Investments (Unaudited)

Statements of Investments (unaudited) Franklin Allocation VIP Fund �������������������������������������������������2 Franklin Flex Cap Growth VIP Fund ������������������������������������29 Franklin Global Real Estate VIP Fund ���������������������������������32 Franklin Growth and Income VIP Fund �������������������������������35 Franklin Income VIP Fund ���������������������������������������������������40 Franklin Large Cap Growth VIP Fund ���������������������������������49 Franklin Mutual Global Discovery VIP Fund ������������������������54 Franklin Mutual Shares VIP Fund ����������������������������������������61 Franklin Rising Dividends VIP Fund ������������������������������������67 Franklin Small Cap Value VIP Fund ������������������������������������70 Franklin Small-Mid Cap Growth VIP Fund ���������������������������74 Franklin Strategic Income VIP Fund ������������������������������������79 Franklin U.S. Government Securities VIP Fund ����������������103 Franklin VolSmart Allocation VIP Fund ������������������������������107 Templeton Developing Markets VIP Fund �������������������������116 Templeton Foreign VIP Fund ���������������������������������������������120 Templeton Global Bond VIP Fund �������������������������������������124 Templeton Growth VIP Fund ���������������������������������������������136 Notes to Financial Statements ������������������������������������������140 Not FDIC Insured May Lose Value No Bank Guarantee VIP-Q1PH 1 FRANKLIN TEMPLETON VARIABLE INSURANCE PRODUCTS TRUST Statement of Investments (unaudited), -

Muni Heritage Press Release Final.Pdf

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: August 29, 2017 Contact: Erica Kato 415-271-7717, cell [email protected] **PRESS RELEASE** MUNI HERITAGE WEEKEND CELEBRATES TWO TRANSIT CENTENNIALS This year celebrates 100 years of the J Church line and 100 years of Muni bus service Who: SFMTA and non-profit partner Market Street Railway When: Saturday and Sunday, September 9-10, 2017 10 a.m. to 5 p.m., with family fun activities from noon to 2 p.m. Where: Market Street Railway Museum 77 Steuart Street San Francisco, CA SAN FRANCISCO – The year 1917 was doubly important for the San Francisco Municipal Railway (Muni). It opened the J-Church streetcar line along a scenic route through Dolores Park and over the hill to Noe Valley, and it introduced its first motor buses, after five years of operating streetcars exclusively. This year, for the sixth annual Muni Heritage Weekend, the San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency, which owns and operates Muni, and Market Street Railway, the SFMTA’s nonprofit preservation partner, are joining to celebrate these dual centennials, and mounting a variety of displays and related events to celebrate the positive ongoing role of public transit in the city. “Public transportation is what has kept San Francisco moving and growing developing for well over a century, and is more important today than ever,” says Ed Reiskin, SFMTA Director of Transportation. “Our displays will show just how important Muni has been not only to the city’s past and present, but will also show its vital importance to San Francisco’s future.” On September 9 and 10, from 10 a.m.