The Blues Brothers and the American Constitutional Protection of Hate Speech: Teaching the Meaning of the First Amendment to Foreign Audiences

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download Press Release As PDF File

JULIEN’S AUCTIONS - PROPERTY FROM THE COLLECTION OF STEVE MARTIN PRESS RELEASE For Immediate Release: JULIEN’S AUCTIONS ANNOUNCES PROPERTY FROM THE COLLECTION OF STEVE MARTIN Emmy, Grammy and Academy Award Winning Hollywood Legend’s Trademark White Suit Costume, Iconic Arrow through the Head Piece, 1976 Gibson Flying V “Toot Uncommons” Electric Guitar, Props and Costumes from Dirty Rotten Scoundrels, Dead Men Don’t Wear Plaid, Little Shop of Horrors and More to Dazzle the Auction Stage at Julien’s Auctions in Beverly Hills All of Steve Martin’s Proceeds of the Auction to be Donated to BenefitThe Motion Picture Home in Honor of Roddy McDowall SATURDAY, JULY 18, 2020 Los Angeles, California – (June 23rd, 2020) – Julien’s Auctions, the world-record breaking auction house to the stars, has announced PROPERTY FROM THE COLLECTION OF STEVE MARTIN, an exclusive auction event celebrating the distinguished career of the legendary American actor, comedian, writer, playwright, producer, musician, and composer, taking place Saturday, July 18th, 2020 at Julien’s Auctions in Beverly Hills and live online at juliensauctions.com. It was also announced today that all of Steve Martin’s proceeds he receives from the auction will be donated by him to benefit The Motion Picture Home in honor of Roddy McDowall, the late legendary stage, film and television actor and philanthropist for the Motion Picture & Television Fund’s Country House and Hospital. MPTF supports working and retired members of the entertainment community with a safety net of health and social -

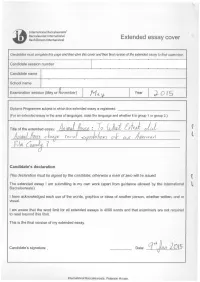

This Cover and Their Final Version Extended

then this cover and their final version extended and whether it is group 1 or Peterson :_:::_.,·. ,_,_::_ ·:. -. \")_>(-_>·...·,: . .>:_'_::°::· ··:_-'./·' . /_:: :·.·· . =)\_./'-.:":_ .... -- __ · ·, . ', . .·· . Stlpervisot1s t~pe>rt ~fld declaration J:h; s3pervi;o(,r;u~f dompietethisreport,. .1ign .the (leclaratton andtfien iiv~.ihe pna:1 ·tersion·...· ofth€7 essay; with this coyerattachedt to the Diploma Programme coordinator. .. .. .. ::,._,<_--\:-.·/·... ":";":":--.-.. ·. ---- .. ,>'. ·.:,:.--: <>=·. ;:_ . .._-,..-_,- -::,· ..:. 0 >>i:mi~ ~;!~;:91'.t~~~1TAt1.tte~) c P1~,§.~p,rmmeht, ;J} a:,ir:lrapriate, on the candidate's perforrnance, .111e. 9q1Jtext ·;n •.w111ctrth~ ..cahdtdatei:m ·.. thft; J'e:~e,~rch.·forf fle ...~X: tendfKI essay, anydifflcu/ties ef1COUntered anq ftCJW thes~\WfJ(fj ()VfJfCOfflf! ·(see .· •tl1i! ext~nciede.ssay guide). The .cpncl(ldipg interview .(vive . vope) ,mt;}y P.fOvidtli .US$ftJf .informf.ltion: pom1r1~nt~ .can .flelp the ex:amr1er award.a ··tevetfot criterion K.th9lisJtcjudgrpentJ. po not. .comment ~pverse personal circumstan9~s that•· m$iiybave . aff.ected the candidate.\lftl'1e cr.rrtotJnt ottime.spiimt qa;ndidate w~s zero, Jt04 must.explain tf1is, fn particular holft!1t was fhf;Jn ppssible .to ;;1.uthentic;at? the essa~ canciidaJe'sown work. You rnay a-ttachan .aclditfonal sherJtJf th.ere isinspfffpi*?nt f pr1ce here,·.···· · Overall, I think this paper is overambitious in its scope for the page length / allowed. I ~elieve it requires furt_her_ editing, as the "making of" portion takes up too ~ large a portion of the essay leaving inadequate page space for reflections on theory and social relevance. The section on the male gaze or the section on race relations in comedy could have served as complete paper topics on their own (although I do appreciate that they are there). -

Fictional Images of Real Places in Philadelphia

598 CONSTRUCTING IDENTITY Fictional Images of Real Places in Philadelphia A. GRAY READ University of Pennsylvania Fictional images ofreal places in novels and films shadow the city as a trickster, doubling its architecture in stories that make familiar places seem strange. In the opening sequence of Terry Gilliam's recent film, 12 Monkeys, the hero, Bruce Willis,rises fromunderground in the year 2027, toexplore the ruined city of Philadelphia, abandoned in late 1997, now occupied by large animals liberated from the zoo. The image is uncanny, particularly for those familiar with the city, encouraging a suspicion that perhaps Philadelphia is, after all, an occupied ruin. In an instant of recognition, the movie image becomes part of Philadelphia and the real City Hall becomes both more nostalgic and decrepit. Similarly, the real streets of New York become more threatening in the wake of a film like Martin Scorcese's Taxi driver and then more ironic and endearing in the flickering light ofWoody Allen's Manhattan. Physical experience in these cities is Fig. 1. Philadelphia's City Hall as a ruin in "12 Monkeys." dense with sensation and memories yet seized by references to maps, books, novels, television, photographs etc.' In Philadelphia, the breaking of class boundaries (always a Gilliam's image is false; Philadelphia is not abandoned, narrative opportunity) is dramatic to the point of parody. The yet the real city is seen again, through the story, as being more early twentieth century saw a distinct Philadelphia genre of or less ruined. Fiction is experimental life tangent to lived novels with a standard plot: a well-to-do heir falls in love with experience that scouts new territories for the imagination.' a vivacious working class woman and tries to bring her into Stories crystallize and extend impressions of the city into his world, often without success. -

WHO's GUITAR Is That?

2013 KBA -BLUES SOCIETY OF THE YEAR CELEBRATING OUR 25TH YEAR IN THIS ISSUE: -Who’s Guitar is That? -The Colorado-Alabama Connection Volume 26 No3 April/May2020 -An Amazing Story -Johnny Wheels Editor- Chick Cavallero -Blues Boosters Partners -CBS Lifetime Achievement WHO’s GUITAR is Award to Mark Sundermeier -CBS Lifetime Achievement That? Award to Sammy Mayfield By Chick Cavallero -CD Reviews –CBS Members Pages Guitar players and their guitar pet names what’s in a name, eh? Not every guitar player names his CONTRIBUTERS TO THIS ISSUE: guitars, heck be pretty hard since some of them have hundreds, and some big stars have Chick Cavallero, Jack Grace, Patti thousands. Still, there have been a few famous Cavallero, Gary Guesnier, Dr. Wayne ones in the Blues World. Most every blues fan Goins, Michael Mark, Ken Arias, Peter knows who Lucille was, B.B. King’s guitar, right? “Blewzzman” Lauro But why? Well, in 1949 BB was a young bluesman playing at a club in Twist, Arkansas that was heated by a half-filled barrel of kerosene in the middle of the dance floor to keep it warm. A fight broke out and the barrel got knocked over with flaming kerosene all over the wooden floor. “It looked like a river of fire, so I ran outside. But when I got on the outside, I realized I left my guitar inside.” B.B. Said he then raced back inside to save the cheap Gibson L-30 acoustic he was playing …and nearly lost his life! The next day he found out the 2 men who started the fight-and fire- had been fighting over a woman named Lucille who worked at that club. -

2019 National Sports and Entertainment History Bee Round 2

Sports and Entertainment Bee 2018-2019 Prelims 2 Prelims 2 Regulation (Tossup 1) This man stars in an oft-parodied commercial in which he states \Ballgame" before taking a drink of Gatorade Flow. In 2017, this man's newly acquired teammate told him \they say I gotta come off the bench." This man missed nearly the entire 2014-2015 season after suffering a horrific leg injury while practicing for the US National Team. Sam Presti sent Domantas Sabonis and Victor Oladipo to the Indiana Pacers in exchange for this player, who then surprisingly didn't bolt to the Lakers in the 2018 off-season. For the point, name this player who formed an unsuccessful \Big Three" with Carmelo Anthony and Russell Westbrook on the Oklahoma City Thunder. ANSWER: Paul Clifton Anthony George (accept PG13) (Tossup 2) This series used Ratatat's \Cream on Chrome" as background music for many early episodes. Side projects of this series include a \Bedtime" version featuring literature readings and an educational \Basics" version. This series' 2019 April Fools' Day gag involved the a 4Kids dub of Pokemon claiming that Brock loved jelly donuts. This series celebrated million-subscriber benchmarks with episodes featuring the Taco Town 15-layer taco and the Every-Meat Burrito and Death Sandwich from Regular Show. For the point, name this YouTube channel starring Andrew Rea, who cooks various foods as inspired by popular culture. ANSWER: Binging with Babish (Tossup 3) The creators of this game recently announced a \Royal" edition which will add a third semester of gameplay. In April 2019, a heavily criticzed Kotaku article claimed that this game's theme song, \Wake up, Get up, Get out there," contains a slur against people with learning disabilities. -

Bluestransport Skapad: 2005-02-16 Redigerad: 2016-03-06

Bluestransport Skapad: 2005-02-16 Redigerad: 2016-03-06 Filmen the Blues Brothers, fråm 1980, handlar om två bröder, Jake och Elwood Blues (spelade av John Belushi och Dan Aykroyd), som försöker samla ihop sitt gamla band för att att kunna få in pengar så att de kan rädda barnhemmet där de växte upp. De hamnar i en massa trubbel och ett visst fordon är nästan varje gång inblandat, Bluesmobilen, Blues Brothers bil. Blues Brothers i förgrunden och Bluesmobilen i bakgrunden. Bluesmobilen var en Dodge Monaco Sedan från 1974 som var målad svart och vit som en före detta polisbil. Denna model var vanlig som polisbil i USA under 1970-talet. I filmen säger Elwood: "I picked it up at the Mount Prospect City polisen auction last spring. It's an old Mount Prospect Police Car." Bilarna som användes i filmen var inte gamla bilar från Mount Prospect City Police, även om polisdistriktet existerar, för att Mt Prospects polisens bilar hade svarta säten, men Bluesmobilen hade ljusbruna säten. Ljusbruna säten är att föredra i varmare områden som till exempel Californien, de svarta sätena blev för varma. Dessutom finns det bilder med highway patrol-bilar Sida 1 av 5 från Californien som har vertikala stänger i fronten precis som Bluesmobilen. Förmodligen använde man i filmen gamla highway patrol-bilar från Californien. Polisutrustningen på Dodge Monaco inkluderade en 440 cui (7,2 liter) stor motor, som Elwood nämner i filmen när han beskriver bilen för Jake efter att ha hämtat honom från fängelset: "It's got a cop motor, a four hundred and forty cubic inch plant, it's got cop tires, cop suspension, cop shocks, it was a model made before catalytic converters so it'll run good on regular gas." Elwood säger det inte, men självklart är det en V8, vad annars i en amerikansk "fullsizare"? Motorn har 270 hk och 500 Nm:s vridmoment. -

East Bristol Auctions

East Bristol Auctions Games, Trains & Automobiles TOY SALE - Worldwide 1 Hanham Business Park Postage, Packing & Delivery Available On All Items, see Memorial Road www.eastbristol.co.uk Bristol BS15 3JE United Kingdom Viewing Friday 28th July 9am - 5pm Started 29 Jul 2017 09:55 BST Lot Description An original 1:18 scale diecast model 1974 Dodge Monaco Sedan Police Car ' The Bluesmobile ' from The Blues Brothers movie. 1 Appears mint, within the original display box. Made by Joyride ERTL. A rare and original 1985 Dr Who Annual panel of artwork. Depicting Colin Baker as The Doctor. Measures approx; 33cm x 44cm. 2 Watercolour and ink. Can be seen on pages 6 and 7 of the 1985 annual. An original vintage 1980's Kenner made The Real Ghostbusters carded action figure of Peter Venkman 'And Ghoulgroan Ghost.' The 3 figure still sealed to the original cardback, untouched. A Scalextric ' Vintage Collection ' C305 4 1/2 Litre Bentley ' 1:32 scale slot racing car. Appears mint, within a very near mint original 4 display box (the rear flap never having been folded). An original vintage Corgi diecast model Chipperfields Circus 511 ' Performing Poodles .' Contents appear near mint, likely unused, 5 within a very near mint original box. An original vintage Japanese made ' Modern Toys Co.' battery operated tinplate ' Space Ranger No.3 ' with spaceman UFO toy. No. 6 4722. Within its original box with original card top protector. Contents mint. Rare. 7 A Hornby 00 gauge railway trainset locomotive R078 Flying Scotsman. Appears unused, within the original box. A fantastic original precision diecast Sun Star made 1:24 scale Routemaster model bus '2908 RM 870 - WLT 870 First Production 8 Routemaster With A Leyland Engine'. -

Film Guide September 2018

FILM GUIDE SEPTEMBER 2018 www.loftcinema.org THE FILMS OF EDGAR WRIGHT, ALL THROUGH SEPTEMBER! THE ALL-NITE SCREAM-O-RAMA, SATURDAY, SEPTEMBER 29TH! ENJOY BEER & WINE AT THE LOFT CINEMA! We also offer Fresco Pizza*, Tucson Tamale Factory Tamales, Burritos from Tumerico, Ethiopian Wraps from Cafe Desta and Sandwiches from the 4th Ave. Deli, along with organic popcorn, craft chocolate bars, vegan cookies and more! *Pizza served after 5pm daily. SEPTEMBER 2018 SPECIAL ENGAGEMENTS 4-32 SOLAR CINEMA 4, 16, 20 BEER OF THE MONTH: LOFT MEMBERSHIPS 5-6 ALL DAY IPA NT LIVE 7 FOUNDERS BREWING COMPANY LOFT JR. 9 ONLY $3.50 ALL THROUGH SEPTEMBER! LOFT STAFF SELECTS 14 ESSENTIAL CINEMA 15 NEW AT THE LOFT CINEMA! SCIENCE ON SCREEN 25 The Loft Cinema now offers Closed Captions and Audio SCREAM-O-RAMA 27-28 Descriptions for films whenever they are available. Check our COMMUNITY RENTALS 32-33 website to see which films offer this technology. NEW FILMS 35-44 REEL READS SELECTION 40 FILM GUIDES ARE AVAILABLE AT: MONDO MONDAYS 45 • aLoft Hotel • First American Title • Rogue Theatre • Antigone Books • Fresco Pizza • Santa Barbara Ice Cream CULT CLASSICS 46 • Aqua Vita • Fronimos • Shot in the Dark Café • AZ Title Security • Heroes & Villains • Southern AZ AIDS THE LOFT CINEMA • Bentley’s • Hotel Congress Foundation • SW U of Visual Arts 3233 E. Speedway Blvd. • Black Crown Coffee • How Sweet It Was • Ted’s Country Store Tucson, AZ 85716 • Bookmans • Humanities Seminars • Bookstop • Imagine Barber Shop • Time Market SHOWTIMES: 520-795-7777 • Brooklyn Pizza -

New Years Eve Films

Movies to Watch on New Year's Eve Going Out Is So Overrated! This year, New Year’s Eve celebrations will have to be done slightly differently due to the pandemic. So, the Learning Curve thought ‘Why not just ring in 2021 with some feel-good movies in your comfy PJs instead?’ After all, everyone knows that the best way to turn over a new year is snuggled up in front of the TV with a hot beverage in your hand. The good news is, no matter how you want to feel going into the next year, there’s a movie on this list that’ll deliver. Best of all — you won’t wake up the next day and begin January with a hangover! Godfather Part II (1974) Director: Francis Ford Coppola Starring: Al Pacino, Robert De Niro, Robert Duvall Continuing the saga of the Corleone crime family, the son, Michael (Pacino) is trying to expand the business to Las Vegas, Hollywood and Cuba. They delve into double crossing, greed and murder as they all try to be the most powerful crime family of all time. Godfather part II is hailed by fans as a masterpiece, a great continuation to the story and the best gangster movie of all time. This is a character driven movie, as we see peoples’ motivations, becoming laser focused on what they want and what they will do to get it. Although the movie is a gripping slow crime drama, it does have one flaw, and that is the length of the movie clocking in at 3 hours and 22 minutes. -

National Lampoon's Animal House

From: Reviews and Criticism of Vietnam War Theatrical and Television Dramas (http://www.lasalle.edu/library/vietnam/FilmIndex/home.htm) compiled by John K. McAskill, La Salle University ([email protected]) N2825 NATIONAL LAMPOON’S ANIMAL HOUSE (USA, 1978) (Other titles: American college; Animal house) Credits: director, John Landis ; writers, Harold Ramis, Douglas Kenney, Chris Miller. Cast: John Belushi, Tim Matheson, John Vernon, Thomas Hulce. Summary: Comedy film set at a 1960s Middle Western college. The members of Delta Tau Chi fraternity offend the straight-arrow and up-tight people on campus in a film which irreverently mocks college traditions. One of the villains is an ROTC cadet who, it is noted at the end of the film, was later shot by his own men in Vietnam. Ansen, David. “Movies: Gross out” Newsweek 92 (Aug 7, 1978), p. 85. Barbour, John. [National Lampoon’s animal house] Los Angeles 23 (Sep 1978), p. 240-43. Bartholomew, David. “National Lampoon’s animal house” Film bulletin 47 (Oct/Nov 1978), p. R-F. Biskind, Peter. [National Lampoon’s animal house] Seven days 2/17 (Nov 10, 1978), p. 33. Bookbinder, Robert. The films of the seventies Secaucus, N.J. : Citadel, 1982. (p. 225-28) Braun, Eric. “National Lampoon’s animal house” Films and filming 25/7 (Apr 1979), p. 31-2. Canby, Vincent. “What’s so funny about potheads and toga parties?” New York times 128 (Nov 19, 1978), sec. 2, p. 17. Cook, David A.. Lost illusions : American cinema in the shadow of Watergate and Vietnam, 1970-1979 New York : Scribner’s, 1999. -

Housing Policy Debate Tracking and Explaining Neighborhood

This article was downloaded by: [University of Pennsylvania], [John D. Landis] On: 18 May 2015, At: 08:30 Publisher: Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK Housing Policy Debate Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rhpd20 Tracking and Explaining Neighborhood Socioeconomic Change in U.S. Metropolitan Areas Between 1990 and 2010 John D. Landisa a Department of City and Regional Planning, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, USA Published online: 18 May 2015. Click for updates To cite this article: John D. Landis (2015): Tracking and Explaining Neighborhood Socioeconomic Change in U.S. Metropolitan Areas Between 1990 and 2010, Housing Policy Debate, DOI: 10.1080/10511482.2014.993677 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10511482.2014.993677 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Taylor & Francis makes every effort to ensure the accuracy of all the information (the “Content”) contained in the publications on our platform. However, Taylor & Francis, our agents, and our licensors make no representations or warranties whatsoever as to the accuracy, completeness, or suitability for any purpose of the Content. Any opinions and views expressed in this publication are the opinions and views of the authors, and are not the views of or endorsed by Taylor & Francis. The accuracy of the Content should not be relied upon and should be independently verified with primary sources of information. Taylor and Francis shall not be liable for any losses, actions, claims, proceedings, demands, costs, expenses, damages, and other liabilities whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with, in relation to or arising out of the use of the Content. -

The Canadianization of the American Media Landscape Eric Weeks

Document generated on 09/26/2021 3:27 a.m. International Journal of Canadian Studies Revue internationale d’études canadiennes Where is There? The Canadianization of the American Media Landscape Eric Weeks Culture — Natures in Canada Article abstract Culture — natures au Canada An increasing number of American film and television productions are filmed Number 39-40, 2009 inCanada. This paper argues that while the Canadianization of the American medialandscape may make financial sense, the trend actually causes harm to URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/040824ar the culturallandscape of both countries. This study examines reasons DOI: https://doi.org/10.7202/040824ar contributing to thetendency to move production to Canada and how recent events have impactedHollywood's northern migration. Further, "authentic" representations of place onthe big and small screens are explored, as are the See table of contents effects that economic runawayproductions—those films and television programs that relocate production due tolower costs found elsewhere—have on a national cultural identity and audiencereception, American and Canadian Publisher(s) alike. Conseil international d'études canadiennes ISSN 1180-3991 (print) 1923-5291 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this article Weeks, E. (2009). Where is There? The Canadianization of the American Media Landscape. International Journal of Canadian Studies / Revue internationale d’études canadiennes, (39-40), 83–107. https://doi.org/10.7202/040824ar Tous droits réservés © Conseil international d'études canadiennes, 2009 This document is protected by copyright law. Use of the services of Érudit (including reproduction) is subject to its terms and conditions, which can be viewed online. https://apropos.erudit.org/en/users/policy-on-use/ This article is disseminated and preserved by Érudit.