Knowledge, Awareness and Use of HIV Services Among the Youth from Nomadic and Agricultural Communities in Tanzania E

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Section Ii: Instructions to Bidders

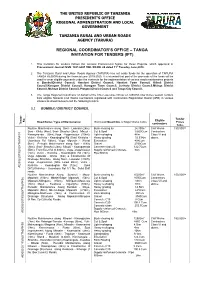

THE UNITED REPUBLIC OF TANZANIA PRESIDENT’S OFFICE REGIONAL ADMINISTRATION AND LOCAL GOVERNMENT TANZANIA RURAL AND URBAN ROADS AGENCY (TARURA) REGIONAL COORDINATOR’S OFFICE – TANGA INVITATION FOR TENDERS (IFT) . 1. This Invitation for tenders follows the General Procurement Notice for these Projects, which appeared in Procurement Journal ISSN: 1821-6021 VOL XII-NO. 24 dated 11th Tuesday June,2019. 2. The Tanzania Rural and Urban Roads Agency (TARURA) has set aside funds for the operation of TARURA TANGA REGION during the financial year 2019-2020. It is intended that part of the proceeds of the funds will be used to cover eligible payments under the contracts for the implementation of various roads maintenance projects at BumbuliDistrict Council, Handeni District Council, Handeni Town Council, Kilindi District Council,Korogwe District Council, Korogwe Town Council, Lushoto District Council,Mkinga District Council, Muheza District Council, Pangani District Council and Tanga City Council. 3. The Tanga Regional Coordinator on behalf of the Chief executive Officer of TARURA now invites sealed Tenders from eligible National Civil Works Contractors registered with Contractors Registration Board (CRB) in various classes as shown below to bid the following tenders. 3.1 BUMBULI DISTRICT COUNCIL Tender Eligible No. Road Name / Type of Maintenance Estimated Quantities of Major Works Items Prices Tender Tender contractors Tshs. Routine Maintenance along Soni - Lwandai (2km), Bush clearing by 24,300m2 Civil Works 150,000/= Soni - Kihitu (4km), Soni- Shashui (2km), Mbuzii - Cut & Spoil 9,600Cum Contractors Kwangwenda (6km),Vuga -Vugamission (10km), Light reshaping 4Km Class VI and Vulini - Kivilicha - Kwandoghoi Rd (5km) Kiviricha - Heavy grading 32.53Km above. -

Effect of Training Program on Employee Retention in Tanzania: a Case Study of Kilindi District Council in Tanga Region

The University of Dodoma University of Dodoma Institutional Repository http://repository.udom.ac.tz Business Master Dissertations 2015 Effect of training program on employee retention in Tanzania: A case study of Kilindi district council in Tanga region Lusewa, Hussein O. The University of Dodoma Lusewa, H. O. (2015). Effect of training program on employee retention in Tanzania: A case study of Kilindi district council in Tanga region http://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12661/1232 Downloaded from UDOM Institutional Repository at The University of Dodoma, an open access institutional repository. EFFECT OF TRAINING PROGRAM ON EMPLOYEE RETENTION IN TANZANIA: A CASE STUDY OF KILINDI DISTRICT COUNCIL IN TANGA REGION By Hussein O. Lusewa Dissertation Submitted for Partial Fulfillment for the Award of the Degree of Masters of Business Administration of University of Dodoma The University of Dodoma September, 2015 CERTIFICATION The undersigned certifies that has read and hereby recommends for acceptance by the University of Dodoma a dissertation entitled “Effect of Training Program on Employee Retention in Tanzania: A Case Study of Kilindi District Council in Tanga Region”, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Business Administration of the University of Dodoma. Signature......................... Dr Mark Paul Diyammi (SUPERVISOR) Date......................................... i DECLARATION AND COPYRIGHT I, Hussein O. LUSEWA declare that; this Dissertation is my own original work and that it has not been presented and will not be presented to any other University for a similar or any other degree award. Signature..................................... No part of this dissertation may be reproduced, store in any retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means without prior written permission of the author or the University of Dodoma. -

Report on the State of Pastoralists' Human Rights in Tanzania

REPORT ON THE STATE OF PASTORALISTS’ HUMAN RIGHTS IN TANZANIA: SURVEY OF TEN DISTRICTS OF TANZANIA MAINLAND 2010/2011 [Area Surveyed: Handeni, Kilindi, Bagamoyo, Kibaha, Iringa-Rural, Morogoro, Mvomero, Kilosa, Mbarali and Kiteto Districts] Cover Picture: Maasai warriors dancing at the initiation ceremony of Mr. Kipulelia Kadege’s children in Handeni District, Tanga Region, April 2006. PAICODEO Tanzania Funded By: IWGIA, Denmark 1 REPORT ON THE STATE OF PASTORALISTS’ HUMAN RIGHTS IN TANZANIA: SURVEY OF TEN DISTRICTS OF TANZANIA MAINLAND 2010/2011 [Area Surveyed: Handeni, Kilindi, Bagamoyo, Kibaha, Iringa-Rural, Morogoro-Rural, Mvomero, Kilosa, Mbarali and Kiteto Districts] PARAKUIYO PASTORALISTS INDIGENOUS COMMUNITY DEVELOPMENT ORGANISATION-(PAICODEO) Funded By: IWGIA, Denmark i REPORT ON THE STATE OF PASTORALISTS’ RIGHTS IN TANZANIA: SURVEY OF TEN DISTRICTS OF TANZANIA MAINLAND 2010/2011 Researchers Legal and Development Consultants Limited (LEDECO Advocates) Writer Adv. Clarence KIPOBOTA (Advocate of the High Court) Publisher Parakuiyo Pastoralists Indigenous Community Development Organization © PAICODEO March, 2013 ISBN: 978-9987-9726-1-6 ii TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ..................................................................................................... vii FOREWORD ........................................................................................................................viii Legal Status and Objectives of PAICODEO ...........................................................viii Vision ......................................................................................................................viii -

NI 43-101 Technical Report

NI 43-101 Technical Report on the Handeni Property centred at 39.97°E, 5.753°S Tanga Province, Kilindi District Tanzania For Canaco Resources Inc 500-602 West Hasting Street Vancouver, BC V6B 1P2 Canada By EurGeol Dr. S. M. Archibald, PGeo Aurum Exploration Services March 1st 2011 Aurum Exploration Services TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY..................................................................................................................... 7 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY..................................................................................................................... 7 2. INTRODUCTION AND TERMS OF REFERENCE.................................................................................. 11 3. RELIANCE ON OTHER EXPERTS....................................................................................................... 12 4. PROPERTY DESCRIPTION AND LOCATION ...................................................................................... 13 TENURE RIGHTS (HANDENI PROPERTY) ...........................................................................................................13 TENURE RIGHTS (GENERAL) ..........................................................................................................................16 5. ACCESSIBILITY, CLIMATE, LOCAL RESOURCES, INFRASTRUCTURE AND PHYSIOGRAPHY.................. 20 ACCESSIBILITY .............................................................................................................................................20 CLIMATE ....................................................................................................................................................21 -

Appendices to Vol 4B

Vote 86 Tanga Region Councils in the Region Council District Councils Code 2018 Tanga City Council 2025 Korogwe Town Council 2038 Handeni Town Council 3069 Muheza District Council 3070 Pangani District Council 3071 Korogwe District Council 3072 Handeni District Council 3073 Lushoto District Council 3093 Kilindi District Council 3106 Mkinga District Council 3141 Bumbuli District Council 2 Vote 86 Tanga Region Council Development Budget Summary Local and Foreign 2014/15 Code Council Local Foreign Total 2018 Tanga City Council 6,284,528,000 4,055,726,000 10,340,254,000 2025 Korogwe Town Council 835,355,000 2,133,500,000 2,968,855,000 2038 Handeni Town Council 0 0 0 3069 Muheza District Council 1,724,971,000 2,109,900,000 3,834,871,000 3070 Pangani District Council 1,437,699,000 1,452,376,000 2,890,075,000 3071 Korogwe District Council 2,037,310,000 1,855,108,000 3,892,418,000 3072 Handeni District Council 2,584,232,000 2,273,114,000 4,857,346,000 3073 Lushoto District Council 3,092,479,000 2,451,378,000 5,543,857,000 3093 Kilindi District Council 3,223,981,000 1,940,690,000 5,164,671,000 3106 Mkinga District Council 1,878,651,000 1,255,017,000 3,133,668,000 3141 Bumbuli District Council 2,547,702,000 1,120,279,000 3,667,981,000 Total 25,646,908,000 20,647,088,000 46,293,996,000 3 Vote 86 Tanga Region Code Description 2012/2013 2013/2014 2014/2015 Actual Expenditure Approved Expenditure Estimates Local Foreign Local Foreign Local Foreign Total Shs. -

Northern Zone Regions Investment Opportunities

THE UNITED REPUBLIC OF TANZANIA PRIME MINISTER’S OFFICE REGIONAL ADMINISTRATION AND LOCAL GOVERNMENT Arusha “The centre for Tourism & Cultural heritage” NORTHERN ZONE REGIONS INVESTMENT OPPORTUNITIES Kilimanjaro “Home of the snow capped mountain” Manyara “Home of Tanzanite” Tanga “The land of Sisal” NORTHERN ZONE DISTRICTS MAP | P a g e i ACRONYMY AWF African Wildlife Foundation CBOs Community Based Organizations CCM Chama cha Mapinduzi DC District Council EPZ Export Processing Zone EPZA Export Processing Zone Authority GDP Gross Domestic Product IT Information Technology KTC Korogwe Town Council KUC Kilimanjaro Uchumi Company MKUKUTA Mkakati wa Kukuza Uchumi na Kupunguza Umaskini Tanzania NDC National Development Corporation NGOs Non Government Organizations NSGPR National Strategy for Growth and Poverty Reduction NSSF National Social Security Fund PANGADECO Pangani Development Corporation PPP Public Private Partnership TaCRI Tanzania Coffee Research Institute TAFIRI Tanzania Fisheries Research Institute TANROADS Tanzania National Roads Agency TAWIRI Tanzania Wildlife Research Institute WWf World Wildlife Fund | P a g e ii TABLE OF CONTENTS ACRONYMY ............................................................................................................ii TABLE OF CONTENTS ........................................................................................... iii 1.0 INTRODUCTION ..............................................................................................1 1.1 Food and cash crops............................................................................................1 -

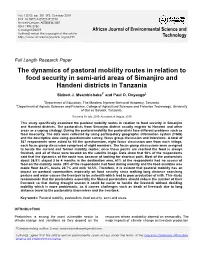

The Dynamics of Pastoral Mobility Routes in Relation to Food Security in Semi-Arid Areas of Simanjiro and Handeni Districts in Tanzania

Vol. 13(10), pp. 381-392, October 2019 DOI: 10.5897/AJEST2019.2730 Article Number: AE588E361887 ISSN: 1996-0786 Copyright ©2019 African Journal of Environmental Science and Author(s) retain the copyright of this article http://www.academicjournals.org/AJEST Technology Full Length Research Paper The dynamics of pastoral mobility routes in relation to food security in semi-arid areas of Simanjiro and Handeni districts in Tanzania Sixbert J. Msambichaka1* and Paul O. Onyango2 1Department of Education, The Mwalimu Nyerere Memorial Academy, Tanzania. 2Department of Aquatic Sciences and Fisheries, College of Agricultural Sciences and Fisheries Technology, University of Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. Received 10 July, 2019; Accepted 28 August, 2019 This study specifically examined the pastoral mobility routes in relation to food security in Simanjiro and Handeni districts. The pastoralists from Simanjiro district usually migrate to Handeni and other areas as a coping strategy. During the pastoral mobility the pastoralists face different problems such as food insecurity. The data were collected by using participatory geographic information system (PGIS) and the descriptive data using questionnaire survey, focus group discussion and interviews. A total of 367 respondents were asked to fill the questionnaire, eight focus discussion one from each village, each focus group discussion comprised of eight members. The focus group discussions were assigned to locate the current and former mobility routes; once these points are reached the food is always finished, and all of these were located on the satellite image. Data show that 58% of the respondents said that the dynamics of the route was because of looking for shortcut path. -

LAND BASED CONFLICT SITUATIONAL and TRENDS ANALYSISCARE in TANZANIA International in Tanzania

LAND BASED CONFLICT SITUATIONAL AND TRENDS ANALYSISCARE IN TANZANIA International in Tanzania PASTORALIST Situational & Trends Analysis: Land Based Conflict in Tanzania May 2016 IDC Ltd LAND BASED CONFLICT SITUATIONAL AND TRENDS ANALYSIS IN TANZANIA ACKNOWLEDGMENTS IDC would like to thank members of CARE International for all their help and cooperation, with a special mention to Madubi Marcely who coordinated this research. On the ground, the Tanzanian Natural Resource Forum (TNRF), provided invaluable input on the myriad of issues and complexities that surround land based conflicts in Tanzania. I would especially like to thank Zacharia Faustin who set up the two workshops in Arusha and led the lively discussions with some of the Pastoralists Programme CSOs leaders. Authors: Ally Bedford and the IDC Team Tanzania Executive Summary Report Sections Section 1 Introduction Section 2 Land Conflict Trends Section 3 Drivers of Land Conflicts Section 4 Case Studies Section 5 Recommendations Section 6 Conclusions Annex 1 Acronyms Annex 2 Government Conflicts Records Annex 3 Case Studies Annex 4 Evictions Annex 5 Policy Brief Annex 6 Facts and Stats Annex 7 Land Use Planning Review Annex 8 TOR and Methodology Annex 9 Bibliography Annex 10 Appendices Available Appendices List Video Viewings at: https://youtu.be/QcM‐0uXoZzY May 2016 IDC Ltd LAND BASED CONFLICT SITUATIONAL AND TRENDS ANALYSIS IN TANZANIA EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The background of the Land Conflict Situational and Trends Analysis in Tanzania is based on the need to understand the growing incidences of violent conflicts arising in recent times. Despite a range of interventions through the Pastoralist Programme (PP) managed by Care Int., and TNRF (supported by IrishAid), land based conflicts seem to have been increasing. -

The Extractive Resource Industry in Tanzania

The Extractive Resource Industry in Tanzania: Resource The Extractive The Extractive Resource Industry in Tanzania: Status and challenges of the mining sector The existing mineral wealth in a country should be a blessing. However the experience in some countries shows that this can prove to be very problematic instead. This publication is inspired by the increasing discovery of minerals in East Africa and the concern about their impact on the future of the region. It argues that if timely investments are made in promoting and implementing good practices in this sector, the problems that have plagued other resource-rich countries can be avoided in Status and challenges of the mining sector East Africa. This report, a product of a process that has engaged various industry stakeholders focuses on Tanzania, which is a relatively late arrival to large-scale mining. It maps out the performance of the mining sector as one component of Tanzania’s extractive resource industry (ERI) and analyses the interactions of the different stakeholders over time. It argues that although there are a number of challenges faced by the ERI sector, Tanzania could yet become one of the best performers in her class. However this will require hard work and investments by all stakeholders. By providing information on the challenges and implications of the current state of the ERI in Tanzania, this report wishes to contribute to the on going discourse and efforts to improve the performance of the ERI in Tanzania in a way that incorporates public accountability and transparency as well as increased participation and benefit to the Tanzanian population. -

From the Director's Desk

A Quarterly Newsletter from Tanzania, Issue No. 21, October-December, 2017 HABARI From the Director’s Desk Our Esteemed HABARI Readers. We are excited to release our end of year newsletter Oct-December, 2017 that highlights the work of Amref Health Africa in Tanzania especially on successes, call for action and a way forward. We are fast approaching the very end of 2017 and it is a right time for us to reflect on what we have achieved and define how best we can improve for impacting the lives of communities especially those that are faced with the most pressing health needs. Achieving our vision of Lasting health change in Africa that values the wellbeing of Tanzanians and others is not something we can do alone, strengthening our strategic partnerships is one of our major building blocks. We value our partners who are contributing in making changes that reflect our vision, which is key to the community we serve. I wish to acknowledge the hard work of Amref staff, our supporters who make what we do possible and the Dr. Florence Temu community that we worked with throughout 2017 for the great working relationship and engagement. Country Director “More Midwives, For Safe Delivery” Shinyanga - Youth Reaching their On a partly rainy morning of November 4, 2017, the Vice President of The United Dreams in DREAMS Republic of Tanzania, Hon. Mama Samia Suluhu Hassan and Hon. Ummy Mwalimu, Amref Health Africa in Tanzania has officially launched Minister for Health, Community Development, Gender, Elderly and Children, led the DREAMS Innovation Challenge “ Keeping Girls in School” over 1700 Dar es Salaam residents in Amref’s Stand up for African Mothers (SU4AM) Project that aims at reducing HIV risks among adolescent fundraising charity walk. -

The Culture of “Silent Sexuality” Amongst the Shambala of Tanzania: Towards an Intercultural Approach in the Pastoral Ministry

THE CULTURE OF “SILENT SEXUALITY” AMONGST THE SHAMBALA OF TANZANIA: TOWARDS AN INTERCULTURAL APPROACH IN THE PASTORAL MINISTRY By Eberhardt Ngugi Shemsanga A Dissertation Submitted in Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) Department of Practical Theology and Missiology in the Faculty of Theology at the University of Stellenbosch Promoter: Dr. Christo Thesnaar MARCH 2013 Stellenbosch University http://scholar.sun.ac.za DECLARATION I, the undersigned, hereby declare that the work contained in this dissertation is my own original work, and that I have not previously in its entirety or in part submitted it at any university for a degree. Signature................................. Date......................................... Copyright © 2013 Stellenbosch University All rights reserved i Stellenbosch University http://scholar.sun.ac.za ABSTRACT SOLI DEO GLORIA This dissertation aims at discussing the influence of two eminent trends on African culture: modernity and globalization with special reference to the culture of silent sexuality as understood and practiced by the Shambala of Tanzania. It is based on secondary data collected through review of studies, reports, policy documents and surveys from various data sets from national, regional and international organizations. The two trends have not only transported the good side of the economic and social development across the globe and connected people from different cultures or nations in the world, but have also changed the culture of host communities. For example, the change from collectivism social structure that characterizes African society to individualism social structure that characterises the market-oriented culture of western society. This change indicates that without doubt “globalization and modernity are the most important and developed theories of the twentieth century” (Ritzer 2008:230). -

Innovative Agricultural Research Initiative (Iagri) Final Report

Innovative Agricultural Research Initiative (iAGRI) Final Report Cooperative Agreement Number: 621-A-00-11-000090-00 Activity Start Date and End Date: March 1, 2011 to August 27, 2017 AOR Name: David Charles Submitted by: Mark Erbaugh Ohio State University (OSU) Office of International Programs in Agriculture 160 Bevis Hall 1080 Carmack Road Columbus, OH 43210 Tel: (614) 292-7252 Fax: (614) 292-1757 This document was produced for review by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). July 2008 1 Table of Contents 1. Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. 5 1.1 Program Description ............................................................................................................................... 5 1.2 Project Objectives ................................................................................................................................... 6 1.3 Balancing Intermediate and Long-term Results ..................................................................................... 6 1.4 Overview of Activities ............................................................................................................................. 6 1.5 Monitoring and Evaluation ..................................................................................................................... 9 2. Project Outcomes Measured by Formal Indicators of Intermediate Results ...............................................