Artisans in the North Carolina Backcountry

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2021 Wachovia Historical Society 125Th Annual Meeting—Oct

WT The Wachovia Tract WT A Publication of the Wachovia Historical Society Volume 21, Issue 1 Spring 2021 Wachovia Historical Society 125th Annual Meeting—Oct. 20 by Paul F. Knouse, Jr. and Johnnie P. Pearson The 125th Annual Meeting of the Wachovia Historical Society was held virtually last Oc- tober 20, 2020, a change in our original plans for the meeting due to the pandemic. WHS is most grateful to Mr. Erik Salzwedel, Business Manager of the Moravian Music Foundation. Erik did a masterful job of working with Annual Meeting chair, Johnnie P. Pearson, to string together music recordings, presentations by WHS Board Members, the Annual Oration, and the presentation of the Archie K. Davis Award in a seamless video production of our annual meeting Inside Spring 2021 on WHS’s own You Tube channel. We are also pleased that those una- ble to view the meeting “live” may still view the video at any time on this channel. Thank you, Erik and Johnnie, and all participants, for your work and for making it possible to continue our Annual Meet- 125th Annual Meeting…...pp. 1-5 ing tradition. Renew Your Membership.…...p.5 The October 20th telecast began with organ music by Mary Louise 2020 Archie K. Davis Award Kapp Peeples from the CD, “Sing Hallelujah,” and instrumental mu- Winner…………….…….....p. 6 sic from the Moravian Lower Brass in the CD, “Harmonious to President’s Report…….……..p. 7 Dwell.” Both CD’s are produced by and available for sale from the 126th Annual Meeting…..…..p. 8 Moravian Music Foundation (see covers Join the Guild!.................…..p. -

Salem Academy Alumnae: Online Community

{Salem Academy} MAGAZINE 2009 SALEM ACADEMY Magazine Susan E. Pauly SALEM ACADEMY President Karl J. Sjolund Head of School Vicki Williams Sheppard C’82 ALUMNAE: Vice President of Institutional Advancement Alumnae Office ONLINE Megan Ratley C’06, Director of Academy Alumnae Relations COMMUNITY Published by the Office of Communications and Public Relations In the coming months we will be implementing Jacqueline McBride, Director Ellen Schuette, Associate Director an online community for all Academy Contributing Writers: Karl Sjolund, Lucia Uldrick, Wynne Overton, alumnae to use through the school website: Megan Ratley, Lorie Howard, . Rose Simon, Ellen Schuette and www.salemacademy.com Mary Lorick Thompson After logging in with a unique username and Designer: Carrie Leigh Dickey C’00 Photography: Alan Calhoun, Allen password, alumnae will be able to submit and Aycock. Class reunion photos by read class notes, submit bio updates, register Snyder Photography. for reunion weekend and other events, as The Salem Academy Magazine is pub- well as many other exciting things. lished by Salem Academy, 500 East Salem Avenue, Winston-Salem, North Carolina 27101. Please check back often and contact the Alumnae This publication is mailed to alumnae, Office with any questions or comments! faculty, staff, parents and friends of Salem. Salem Academy welcomes qualified Megan Ratley C’06 students regardless of race, color, national origin, sexual orientation, religion or dis- Salem Academy ability to all the rights, privileges, pro- Director of Alumnae Relations grams and activities of this institution. 336/721-2664 For additional information about any programs or events mentioned in this publications, please write, call, email or visit: Alumnae Office Salem Academy SAVE THE DATE: 500 East Salem Avenue Winston-Salem, NC 27101 336/721-2664 REUNION Email: [email protected] Website: www.salemacademy.com WEEKEND On the cover: The Salem Academy graduating class of 2009. -

Old Salem Historic District Design Review Guidelines

Old Salem Historic District Guide to the Certificate of Appropriateness (COA) Process and Design Review Guidelines PREFACE e are not going to discuss here the rules of the art of building “Was a whole but only those rules which relate to the order and way of building in our community. It often happens due to ill-considered planning that neighbors are molested and sometimes even the whole community suffers. For such reasons in well-ordered communities rules have been set up. Therefore our brotherly equality and the faithfulness which we have expressed for each other necessitates that we agree to some rules and regulation which shall be basic for all construction in our community so that no one suffers damage or loss because of careless construction by his neighbor and it is a special duty of the Town council to enforce such rules and regulations. -From Salem Building” Regulations Adopted June 1788 i n 1948, the Old Salem Historic District was subcommittee was formed I established as the first locally-zoned historic to review and update the Guidelines. district in the State of North Carolina. Creation The subcommittee’s membership of the Old Salem Historic District was achieved included present and former members in order to protect one of the most unique and of the Commission, residential property significant historical, architectural, archaeological, owners, representatives of the nonprofit and cultural resources in the United States. and institutional property owners Since that time, a monumental effort has been within the District, and preservation undertaken by public and private entities, and building professionals with an nonprofit organizations, religious and educational understanding of historic resources. -

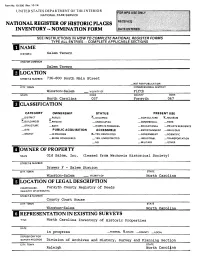

Hclassification

Form No. 10-300 (Rev. 10-74) UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOWTO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS [NAME HISTORIC Salem Tavern AND/OR COMMON Salem Tavern LOCATION STREET& NUMBER 736-800 South Main Street _NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY. TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Winston-Salem __. VICINITY OF Fifth STATE CODE COUNTY CODE North Carolina 037 Forsyth 067 HCLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE _DISTRICT —PUBLIC •^-OCCUPIED _ AGRICULTURE X_MUSEUM ^LBUILDINGIS) —PRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL —PARK —STRUCTURE _BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT _JN PROCESS X_YES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC _ BEING CONSIDERED — YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION _ NO —MILITARY —OTHER: OWNER OF PROPERTY NAME Old Salem, Inc. (leased from Wachovia Historical Society) STREET & NUMBER Drawer F - Salem Station CITY. TOWN STATE Winston-Salem _ VICINITY OF North Carolina LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE, Forsyth County Registry of Deeds REGISTRY OF DEEDS,ETC. STREET & NUMBER County Court House CITY. TOWN STATE Winston-Salem North Carolina | REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE North Carolina Inventory of Historic Properties DATE in progress —FEDERAL X.STATE —COUNTY —LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS Division of Archives and History, Survey and Planning Section CITY. TOWN STATE Raleigh North Carolina DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE —UNALTERED ^.ORIGINAL SITE .^EXCELLENT —DETERIORATED _GOOD —RUINS FALTERED restored MOVED DATE- _FAIR _UNEXPOSED DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE The Salem Tavern is located on the west side of South Main Street (number 736-800) in the restored area of Old Salem, now part of Winston-Salem, North Carolina. -

Z T:--1 ( Signa Ure of Certifying Ohicial " F/ Date

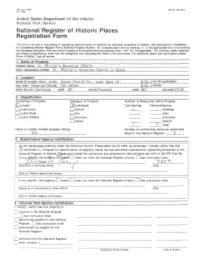

NPS Form 10-900 008 No. 1024-0018 (Rev. 8-86) U National Park Service This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations of eligibility for individual properties or districts. See instructions in Guidelines for Completing National Register Forms (National Register Bulletin 16). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the requested information. If an item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, styles, materials, and areas of significance, enter only the categories and subcategories listed in the instructions. For additional space use continuation sheets (Form 1 0-900a). Type all entries. 1. Name of Property historic name St. Philip's Moravian Church other names/site number St. Philip' s ~1oravian Church in Salem city, town Hinston-Salem, Old Salem vicinity state North Carolina code NC county Forsyth code zip code 27108 Ownership of Property Category of Property Number of Resources within Property KJ private [Zl building(s) Contributing Noncontributing o public-local Ddistrict 1 ___ buildings o public-State DSi1e ___ sites o public-Federal D structure ___ structures Dobject _---,...,--------objects 1 __O_Total Name of related multiple property listing: Number of contributing resources previously N/A listed in the National Register 0 As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this ~ nomination 0 request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National R~g~ter of Historic~nd me~Js the procedural a~d profes~ional r.eq~irements set f~rth .in 36 CFR Part 60. -

Costume Crafts an Exploration Through Production Experience Michelle L

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Master's Theses Graduate School 2010 Costume crafts an exploration through production experience Michelle L. Hathaway Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses Part of the Theatre and Performance Studies Commons Recommended Citation Hathaway, Michelle L., "Costume crafts na exploration through production experience" (2010). LSU Master's Theses. 2152. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses/2152 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Master's Theses by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. COSTUME CRAFTS AN EXPLORATION THROUGH PRODUCTION EXPERIENCE A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts in The Department of Theatre by Michelle L. Hathaway B.A., University of Colorado at Denver, 1993 May 2010 Acknowledgments First, I would like to thank my family for their constant unfailing support. In particular Brinna and Audrey, girls you inspire me to greatness everyday. Great thanks to my sister Audrey Hathaway-Czapp for her personal sacrifice in both time and energy to not only help me get through the MFA program but also for her fabulous photographic skills, which are included in this thesis. I offer a huge thank you to my Mom for her support and love. -

Studying Craft: Trends in Craft Education and Training Participation in Contemporary Craft Education and Training

Studying craft: trends in craft education and training Participation in contemporary craft education and training Cover Photography Credits: Clockwise from the top: Glassmaker Michael Ruh in his studio, London, December 2013 © Sophie Mutevelian Head of Art Andrew Pearson teaches pupils at Christ the King Catholic Maths and Computing College, Preston Cluster, Firing Up, Year One. © University of Central Lancashire. Silversmith Ndidi Ekubia in her studio at Cockpit Arts, London, December 2013 © Sophie Mutevelian ii ii Participation in contemporary craft education and training Contents 1. GLOSSARY 3 2. FOREWORD 4 3. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 5 3.1 INTRODUCTION 5 3.2 THE OFFER AND TAKE-UP 5 3.3 GENDER 10 3.4 KEY ISSUES 10 3.5 NEXT STEPS 11 4. INTRODUCTION 12 4.1 SCOPE 13 4.2 DEFINITIONS 13 4.3 APPROACH 14 5. POLICY TIMELINE 16 6. CRAFT EDUCATION AND TRAINING: PROVISION AND PARTICIPATION 17 6.1 14–16 YEARS: KEY STAGE 4 17 6.2 16–18 YEARS: KEY STAGE 5 / FE 22 6.3 ADULTS: GENERAL FE 30 6.4 ADULTS: EMPLOYER-RELATED FE 35 6.5 APPRENTICESHIPS 37 6.6 HIGHER EDUCATION 39 6.7 COMMUNITY LEARNING 52 7. CONCLUDING REMARKS 56 8. APPENDIX: METHODOLOGY 57 9. NOTES 61 1 Participation in contemporary craft education and training The Crafts Council is the national development agency for contemporary craft. Our goal is to make the UK the best place to make, see, collect and learn about contemporary craft. www.craftscouncil.org.uk TBR is an economic development and research consultancy with niche skills in understanding the dynamics of local, regional and national economies, sectors, clusters and markets. -

Recipes Your Best Pies 39 Focus on Texas Photo Contest: Swings 40 Around Texas List of Local Events 42 Hit the Road Taking in Tyler by Melissa Gaskill

LOCAL ELECTRIC COOPERATIVE EDITION APRIL 2016 Helping Local Libraries Gettysburg Casualty Best Pies. Yum! HATSON! Texas hatmakers have you covered We’re e on a mission to set the neighborhood standard. With the most dependable equipment, we create spectacular spaces. We thrive on the fresh air, the challenge and the results of our efforts. We set the bar high to create a space we’re proud to call our own. kubota.com © Kubota Tractorr Corpporation, 2016 Since 1944 April 2016 FAVORITES 5 Letters 6 Currents 20 Local Co-op News Get the latest information plus energy and safety tips from your cooperative. 33 Texas History Gettysburg’s Last Casualty By E.R. Bills 35 Recipes Your Best Pies 39 Focus on Texas Photo Contest: Swings 40 Around Texas List of Local Events 42 Hit the Road Taking in Tyler By Melissa Gaskill Jeff Biggars applies steam ONLINE as he shapes a hat. TexasCoopPower.com Find these stories online if they don’t FEATURES appear in your edition of the magazine. Observations Cowboy Hatters Texas artisans crown your cranium in Tough Kid, Tough Breaks 8 a grand and storied tradition By Clay Coppedge Story by Gene Fowler | Photos by Tadd Myers Texas USA The Erudite Ranger Community Anchors Enlivening libraries establishes By Lonn Taylor 12 an environment for learning, sharing and loving literacy By Dan Oko NEXT MONTH New Directions in Farming A younger generation seeks alternatives to keep the family business thriving. 33 39 35 42 BIGGARS: TADD MYERS. PLANT: CANDY1812 | DOLLAR PHOTO CLUB ON THE COVER J.W. Brooks handcrafts hats for cowboys and cowgirls at his shop in Lipan. -

The History of the Moravian Church Rooting in Unitas Fratrum Or the Unity of the Brethren

ISSN 2308-8079. Studia Humanitatis. 2017. № 3. www.st-hum.ru УДК 274[(437):(489):(470)] THE HISTORY OF THE MORAVIAN CHURCH ROOTING IN UNITAS FRATRUM OR THE UNITY OF THE BRETHREN (1457-2017) BASED ON THE DESCRIPTION OF THE TWO SETTLEMENTS OF CHRISTIANSFELD AND SAREPTA Christensen C.S. The article deals with the history and the problems of the Moravian Church rooting back to the Unity of the Brethren or Unitas Fratrum, a Czech Protestant denomination established around the minister and philosopher Jan Hus in 1415 in the Kingdom of Bohemia. The Moravian Church is thereby one of the oldest Protestant denominations in the world. With its heritage back to Jan Hus and the Bohemian Reformation (1415-1620) the Moravian Church was a precursor to the Martin Luther’s Reformation that took place around 1517. Around 1722 in Herrnhut the Moravian Church experienced a renaissance with the Saxonian count Nicolaus von Zinzendorf as its protector. A 500 years anniversary celebrated throughout the Protestant countries in 2017. The history of the Moravian Church based on the description of two out of the 27 existing settlements, Christiansfeld in the southern part of Denmark and Sarepta in the Volgograd area of Russia, is very important to understand the Reformation in 1500s. Keywords: Moravian Church, Reformation, Jan Hus, Sarepta, Christiansfeld, Martin Luther, Herrnhut, Bohemia, Protestantism, Bohemian Reformation, Pietism, Nicolaus von Zinzendorf. ИСТОРИЯ МОРАВСКОЙ ЦЕРКВИ, БЕРУЩЕЙ НАЧАЛО В «UNITAS FRATRUM» ИЛИ «ЕДИНОМ БРАТСТВЕ» (1457-2017), ОСНОВАННАЯ НА ОПИСАНИИ ДВУХ ПОСЕЛЕНИЙ: КРИСТИАНСФЕЛЬДА И САРЕПТЫ Христенсен К.С. Статья посвящена исследованию истории и проблем Моравской Церкви, уходящей корнями в «Unitas Fratrum» или «Единое братство», которое ISSN 2308-8079. -

The Milliner Cross Stitch Pattern by Perrette Samouiloff

The Milliner cross stitch pattern by Perrette Samouiloff Manufacturer: Perrette Samouiloff Reference:PER239 Price: $11.99 Options: download pdf file : English Description: The Milliner CROSS STITCH PATTERN READY TO DOWNLOAD, DESIGNED BY Perrette Samouiloff This design is part of a series of cross stitch charts related to needlecrafts. After the Lacemaker, here is a tribute to the fine art of hatmaking. The milliner's trade, which has almost disappeared today, is the art of designing, making, decorating and personalizing hats, fashion accessories par excellence. In this cross stitch pattern, the milliner is at work, needle in hand, in her hat shop, while her customers try various hats on. The hats come in a wide variety of styles and very feminine shapes: wide brim and veil, cloche hats from the thirties, floppy brimmed hats, round caps, straw hats, together with a whole collection of exquisite small hat pins. The title of the embroidery "The Milliner" is embroidered in pretty cursive letters. The design is an adaptation from the French "La Modiste". If you would rather stitch the French version, please contact us after placing the order and we will send you the chart with the original French text (last picture). A cross stitch pattern by Perrette Samouiloff. >> see more patterns related to Fashion and Costumes by Perrette Samouiloff Chart info & Needlework supplies for the pattern: The Milliner Chart size in stitches: 138 x 160(wide x high) Needlework fabric: Aida, Linen or Evenweave, white >> View size in my choice of fabric (fabric calculator) Stitches: Cross stitch, Backstitch, 3/4 cross stitch Chart: Black & White, color detail Threads: DMC Number of colors:1 Themes: hat making workshop, hat shop, fashion, ornamental hat pins >> see all patterns related to Clothes and Fashion accessories (all designers) All patterns on Creative Poppy's website are printable and available for instant download. -

Vital Signs the Intersection of Health & Community Development

Vital Signs The Intersection of Health & Community Development Tweet @phillycdcs Join the Movement Towards An Equitable Philadelphia PACDC Community Development Leadership Institute’s 2019 FORWARD EQUITABLE DEVELOPMENT CONFERENCE Wednesday, June 26th & Thursday June 27th, 2019 KEYNOTE SPEAKER Liz Ogbu A designer, urbanist, and social innovator, Liz is an expert on social and spatial innovation in challenged urban environments Philadelphia globally. Through her multidisciplinary design and innovation consultancy, Studio O, she collaborates with/in communities in need does Better to leverage the power of design to catalyze sustained social impact. Among her honors, when we ALL she is a TED speaker, one of Public Interest Design’s Top 100, and a former Aspen Ideas do Better Scholar. “What if gentrification was about healing communities instead of displacing them?” —Liz Ogbu PHOTO CREDIT: RYAN LASH PHOTOGRAPHY Join 300 community developers, small business entrepreneurs, health practitioners, researchers, artists, educators, and activists committed to working toward a more equitable Philadelphia. Conference attendees will explore innovative pathways to ensuring all Philadelphia’s residents and businesses prosper, network with others striving to undertake equitable development, and be uplifted and energized through moving stories of success and lessons learned. Keynote and workshops on Wednesday, June 26th, and in-depth learning seminars on Thursday, June 27th. CONFERENCE SPONSOR PARTNERS: Jefferson Center for Urban Health/Jefferson Health Systems, -

A Loving Home's a Happy Home 19Th-Century Moravian Parlor Music by Lisetta and Amelia Van Vleck, Carl Van Vleck & F. F. Ha

A Loving Home’s A Happy Home 19th-Century Moravian Parlor Music by Lisetta and Amelia Van Vleck, Carl Van Vleck & F. F. Hagen Rev. Dr. Nola Reed Knouse, Director, Moravian Music Foundation It is often stated that, for Moravians, music is an essential part of life, not something added later on when the essential things have been taken care of. We have long known of the great emphasis the Moravians placed on education of both boys and girls. Over the more than five hundred and fifty years since the founding of the Unitas Fratrum, these two emphases have been woven together into a rich and colorful history of music-teaching and music-making. The renewed Moravian Church in the eighteenth century, following Zinzendorf ’s recognition that men and women in various stages of life have different spiritual expressions, needs, and gifts, encouraged expressions of faith by women as well as by men. While we know of no Moravian women composers of sacred vocal music in the eighteenth century, there survive an immense number of hymn texts written by women—in fact, in an informal overview, the proportion of texts written by women seems to be greater in the 1778 Gesangbuch (German Moravian hymnal) than in the 1995 Moravian Book of Worship. Many of these are ones still known and loved today. Pauline Fox, notes that music manuscript books used from the mid-18th through mid-19th centuries among the Pennsylvania Moravians (like those originating among the Moravians in North Carolina) contain a wide variety of musical styles and genres—hymns, simple devotional songs, popular songs and piano works often appearing very soon after their publication.