Z T:--1 ( Signa Ure of Certifying Ohicial " F/ Date

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Spirit of the Moravian Church 2011 Preface

The Spirit of the Moravian Church 2011 Preface One of the most frequent requests to the Moravian Archives has been for a reprint of Clarence Shawe’s delightful little booklet, The Spirit of the Moravian Church. This e-book edition reproduces that booklet in its original form. In addition, the observations of two other bishops are provided for the insight they give, spanning the centuries, on the Moravian spirit. Bishop Clarence H. Shawe wrote The Spirit of the Moravian Church for the great celebration of our church’s 500th anniversary in 1957. He prepared it in the context of the British Province, and his writing reflects the style of a more gracious age when he was growing up there in the late 19th century. Some of the details and expressions may therefore sound unfamiliar to many American ears of the 21st century. That being said, this is a very solid, enjoyable, and informative work which truly captures the spirit of our worldwide Moravian Church. In doing so it clearly expounds and explores several key characteristics which have shaped our Church for more than 500 years and continue to define it today. As such, it is well worth the reading in this or any other century. Bishop D. Wayne Burkette presented his message of “A Gifted Church, a Giving Church” to the 2008 Insynodal Conference of the Southern Province. As president at the time of the Province’s Provincial Elders Conference and formerly headmaster of Salem Academy, Bishop Burkette offers a distinctly 21st-century view of the gifts of the Moravian Church. -

Old Salem Historic District Design Review Guidelines

Old Salem Historic District Guide to the Certificate of Appropriateness (COA) Process and Design Review Guidelines PREFACE e are not going to discuss here the rules of the art of building “Was a whole but only those rules which relate to the order and way of building in our community. It often happens due to ill-considered planning that neighbors are molested and sometimes even the whole community suffers. For such reasons in well-ordered communities rules have been set up. Therefore our brotherly equality and the faithfulness which we have expressed for each other necessitates that we agree to some rules and regulation which shall be basic for all construction in our community so that no one suffers damage or loss because of careless construction by his neighbor and it is a special duty of the Town council to enforce such rules and regulations. -From Salem Building” Regulations Adopted June 1788 i n 1948, the Old Salem Historic District was subcommittee was formed I established as the first locally-zoned historic to review and update the Guidelines. district in the State of North Carolina. Creation The subcommittee’s membership of the Old Salem Historic District was achieved included present and former members in order to protect one of the most unique and of the Commission, residential property significant historical, architectural, archaeological, owners, representatives of the nonprofit and cultural resources in the United States. and institutional property owners Since that time, a monumental effort has been within the District, and preservation undertaken by public and private entities, and building professionals with an nonprofit organizations, religious and educational understanding of historic resources. -

Hclassification

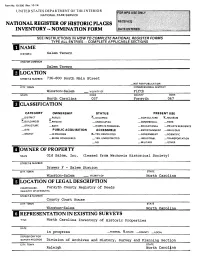

Form No. 10-300 (Rev. 10-74) UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOWTO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS [NAME HISTORIC Salem Tavern AND/OR COMMON Salem Tavern LOCATION STREET& NUMBER 736-800 South Main Street _NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY. TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Winston-Salem __. VICINITY OF Fifth STATE CODE COUNTY CODE North Carolina 037 Forsyth 067 HCLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE _DISTRICT —PUBLIC •^-OCCUPIED _ AGRICULTURE X_MUSEUM ^LBUILDINGIS) —PRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL —PARK —STRUCTURE _BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT _JN PROCESS X_YES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC _ BEING CONSIDERED — YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION _ NO —MILITARY —OTHER: OWNER OF PROPERTY NAME Old Salem, Inc. (leased from Wachovia Historical Society) STREET & NUMBER Drawer F - Salem Station CITY. TOWN STATE Winston-Salem _ VICINITY OF North Carolina LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE, Forsyth County Registry of Deeds REGISTRY OF DEEDS,ETC. STREET & NUMBER County Court House CITY. TOWN STATE Winston-Salem North Carolina | REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE North Carolina Inventory of Historic Properties DATE in progress —FEDERAL X.STATE —COUNTY —LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS Division of Archives and History, Survey and Planning Section CITY. TOWN STATE Raleigh North Carolina DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE —UNALTERED ^.ORIGINAL SITE .^EXCELLENT —DETERIORATED _GOOD —RUINS FALTERED restored MOVED DATE- _FAIR _UNEXPOSED DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE The Salem Tavern is located on the west side of South Main Street (number 736-800) in the restored area of Old Salem, now part of Winston-Salem, North Carolina. -

Constitution of the Moravian Church in America, Southern Province

Constitution of the Moravian Church in America, Southern Province Section 1. Name and Title The name and title of this Province of the Unitas Fratrum shall be the "Moravian Church in America, Southern Province." Section 2. The Government of the Unity The Unity Synod of the Moravian Church is supreme in all things assigned to it by the Constitution of the Unity. In all other affairs of the Unity in the Southern Province, the Government is vested in the Provincial Synod, and in the Boards elected and authorized by the Provincial Synod. Section 3. The Provincial Synod The Provincial Synod has the supreme legislative power of the Province in all things not committed to the Unity Synod. It shall consist of elected delegates and official members; it shall determine the qualification of its own members; it shall prescribe what bodies shall be entitled to representation, and on what basis, and in what manner to be elected. Section 4. Duties and Functions of the Provincial Synod The Provincial Synod shall have power: 1. to carry out the principles of the Moravian Church (Unitas Fratrum) laid down by the Unity Synod for constitution, doctrine, worship and congregational life; 2. to examine and oversee the spiritual and temporal affairs of the Province and its congregations; 3. to legislate in regard to constitution, worship and congregational life for the Province; 4. to provide the vision, direction and expectations for Provincial mission and ministry and to review the results thereof; 5. to elect the Provincial Elders' Conference which shall constitute the administrative board of the Province and which shall be responsible to the Synod for the management of the affairs committed to it; 6. -

The Moravian Church and the White River Indian Mission

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1991 "An Instrument for Awakening": The Moravian Church and the White River Indian Mission Scott Edward Atwood College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the History of Religion Commons, Indigenous Studies Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Atwood, Scott Edward, ""An Instrument for Awakening": The Moravian Church and the White River Indian Mission" (1991). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539625693. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-5mtt-7p05 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. "AN INSTRUMENT FOR AWAKENING": THE MORAVIAN CHURCH AND THE WHITE RIVER INDIAN MISSION A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of History The College of William and Mary in Virginia In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements-for the Degree of Master of Arts by Scott Edward Atwood 1991 APPROVAL SHEET This thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Author Approved, May 1991 <^4*«9_^x .UU James Axtell Michael McGiffert Thaddeus W. Tate, Jr. i i TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGMENTS................................................................................. -

ROLE of the BISHOP of the MORAVIAN CHURCH UNDERSTANDING and PRACTICE of the CZECH PROVINCE Concerning the Attitude to the Role

ROLE OF THE BISHOP OF THE MORAVIAN CHURCH UNDERSTANDING AND PRACTICE OF THE CZECH PROVINCE Concerning the attitude to the role of the bishop of the Moravian Church, the Czech Province carries on the attitude of the Ancient and Renewed Unitas Fratrum. The role of the bishop in the Ancient Moravian Church (Unity of Brethren) The Ancient Unity of Brethren was established as an expression of the desire of a group of brethren around brother Gregor to live together in obedience to the Lord, according to the Scriptures, and following the example of the apostles. This desire of the brethren was a renewal of the early church. An important step was taken in 1467 in Lhotka near Rychnov, when - after long deliberation and prayers – they appointed their own bishops. This was done by drawing lots. In the words of brother Gregor: "We have entrusted the Lord our God, that He has chosen some to the office of apostle in place of His Son beloved Lord Jesus Christ” (Jan Blahoslav, About the Origin of Unity and Her Order). By drawing lots Matthias of Kunwald, Thomas of Prelouč and Elias of Chřenovic were chosen. Brother Gregor then testified that he was ahead of God's revelation that it will be these three. The Ancient Unity understood bishops as successors of the Apostles. Initially, there were three bishops, and later their number was increased to four and then to six. Each bishop (senior) had several assistants (conseniors) to help him; the bishops along with assistants formed the board. The bishops were elected by the synod votes of all the priests (pastors), and were confirmed by current bishops. -

Count Nicholas Ludwig Von Zinzendorf (1700-1760)

Count Nicholas Ludwig von Zinzendorf (1700-1760) Count Nicholas Ludwig von Zinzendorf was born in Dresden on May 26, 1700. He became a leader of the Protestant Reformation and the founder of the Renewed Moravian Church. Zinzendorf built the Moravian Church upon the foundation of Comenius's Revision of The Order of Discipline of the Church of the Brethren. Zinzendorf wrote the Brotherly Agreement of 1727 for the Protestant refugees who had taken refuge on his estate. He soon became the leading theologian of the Moravian Church. The young Count studied theology and submitted to ordination within the Lutheran Church in order to offer political protection and spiritual guidance to the Herrnhut community. Zinzendorf’s theology grew out of Luther's Catechisms, Comenius's records of Brethren teachings and his own experiences in the Herrnhut community. Zinzendorf’s teachings put Christ at the center of the Moravian theology. The Count wrote hymns and litanies which stressed the salvific benefits of Jesus' death upon the cross, and introduced the lovefeast to Moravian life (Sawyer, p. 41 ). Zinzendorf emphasized devotion to the blood of Jesus, organized church bands, designated the role of the Holy Spirit within the Moravian community as the role of a mother (Kinkel, p. 24), and moved the Moravians toward mission work because of his belief that the atonement of Jesus had opened the hearts of all individuals to the voice of the Holy Spirit proclaiming the Good News of salvation (Kinkel, pp. 61-67). Formation Influences from Count Zinzendorf’s Early Life Zinzendorf was born to position, power, and piety. -

Czech-American Protestants: a Minority Within a Minority

Nebraska History posts materials online for your personal use. Please remember that the contents of Nebraska History are copyrighted by the Nebraska State Historical Society (except for materials credited to other institutions). The NSHS retains its copyrights even to materials it posts on the web. For permission to re-use materials or for photo ordering information, please see: http://www.nebraskahistory.org/magazine/permission.htm Nebraska State Historical Society members receive four issues of Nebraska History and four issues of Nebraska History News annually. For membership information, see: http://nebraskahistory.org/admin/members/index.htm Article Title: Czech-American Protestants: A Minority within a Minority Full Citation: Bruce M Garver, “Czech-American Protestants: A Minority within a Minority,” Nebraska History 74 (1993): 150-167 URL of article: http://www.nebraskahistory.org/publish/publicat/history/full-text/NH1993CAProtestants.pdf Date: 3/23/2015 Article Summary: There were few Czech-American Protestants, but they received the assistance of mainline American Protestant denominations in establishing congregations and building meeting houses. They perpetuated the use of the Czech language and did important charitable work. Cataloging Information: Names: František Kún, Jan Pípal, E A Adams, David S Schaff, Will Monroe, Gustav Alexy, Albert Schauffler, Vincenc Písek, A W Clark, Jaroslav Dobiáš, František B Zdrůbek, Bohdan A Filipi, Tomáš G Masaryk, J L Hromádka Place Names: Bohemia; Moravia; Saunders and Colfax Counties, Nebraska; -

The History of the Moravian Church Rooting in Unitas Fratrum Or the Unity of the Brethren

ISSN 2308-8079. Studia Humanitatis. 2017. № 3. www.st-hum.ru УДК 274[(437):(489):(470)] THE HISTORY OF THE MORAVIAN CHURCH ROOTING IN UNITAS FRATRUM OR THE UNITY OF THE BRETHREN (1457-2017) BASED ON THE DESCRIPTION OF THE TWO SETTLEMENTS OF CHRISTIANSFELD AND SAREPTA Christensen C.S. The article deals with the history and the problems of the Moravian Church rooting back to the Unity of the Brethren or Unitas Fratrum, a Czech Protestant denomination established around the minister and philosopher Jan Hus in 1415 in the Kingdom of Bohemia. The Moravian Church is thereby one of the oldest Protestant denominations in the world. With its heritage back to Jan Hus and the Bohemian Reformation (1415-1620) the Moravian Church was a precursor to the Martin Luther’s Reformation that took place around 1517. Around 1722 in Herrnhut the Moravian Church experienced a renaissance with the Saxonian count Nicolaus von Zinzendorf as its protector. A 500 years anniversary celebrated throughout the Protestant countries in 2017. The history of the Moravian Church based on the description of two out of the 27 existing settlements, Christiansfeld in the southern part of Denmark and Sarepta in the Volgograd area of Russia, is very important to understand the Reformation in 1500s. Keywords: Moravian Church, Reformation, Jan Hus, Sarepta, Christiansfeld, Martin Luther, Herrnhut, Bohemia, Protestantism, Bohemian Reformation, Pietism, Nicolaus von Zinzendorf. ИСТОРИЯ МОРАВСКОЙ ЦЕРКВИ, БЕРУЩЕЙ НАЧАЛО В «UNITAS FRATRUM» ИЛИ «ЕДИНОМ БРАТСТВЕ» (1457-2017), ОСНОВАННАЯ НА ОПИСАНИИ ДВУХ ПОСЕЛЕНИЙ: КРИСТИАНСФЕЛЬДА И САРЕПТЫ Христенсен К.С. Статья посвящена исследованию истории и проблем Моравской Церкви, уходящей корнями в «Unitas Fratrum» или «Единое братство», которое ISSN 2308-8079. -

EVENTSFALL 2016 They Are We Film Screening and Discussion, P.3

COURSES FOR COMMUNITY SALEM COLLEGE CULTURAL EVENTSFALL 2016 They Are We Film Screening and Discussion, p.3 SANDRESKY SERIES A Grand Reunion of Pianists!, p.5 Salem Signature First-Year Read - Laila Lalami: The Moor’s Account, p.7 Winston-Salem, NC Winston-Salem, Permit No. 31 No. Permit Winston-Salem, NC 27101 NC Winston-Salem, PAID 601 South Church Street Church South 601 U.S. Postage U.S. SALEM COLLEGE SALEM Non-Profit Engage, Educate, Inspire August October During our Fall 2016 season of cultural 29 Matthew Christopher: 1-2 Salem Bach Festival (p4) events, Salem College seeks to engage, educate, and inspire Abandoned America – 1-2 Salem College Pierrettes through the fine arts, scholarship, and discussion; through Exhibition through October 16 Present Steel Magnolias (p5) the written and spoken word; and through performances of (p8) 4 They Are We Film Screening all kinds. We are proud to present a wide variety of events 29 Joy Ritenour – Looking and Discussion (p3) each year by bringing distinguished authors, performing Around: The Fruit Series – 13 Comenius Symposium (p7) artists, musicians, and visual artists to the Triad, in addition to Exhibition through October 16 14 Center for Women Writers featuring our faculty and students. (p8) Directors’ Cut: Reading and 29 Barbara Pflieger Mory: Conversation (p6) Salem Academy and College has been educating girls and Seeking Peace – Exhibition 18 Roberto Martínez: Classical women for more than 244 years. Today, Salem College offers (p8) through October 16 Guitarist, Composer, and undergraduate majors and minors for young women; graduate Music Researcher (p3) programs in education and music for both women and men; September 20 Colorful Sounds in Concert, non-degree programs through Courses for Community; and a 8 Salem Signature First-Year featuring Roberto Martínez range of degree and certificate programs for women and men, Read: Laila Lalami: The Moor’s (p3) ages twenty-three and older, through the Martha H. -

One Flock, One Shepherd: Lutheran-Moravian Relations

One Flock, One Shepherd: Lutheran-Moravian Relations One Flock, One Shepherd: Lutheran-Moravian Relations Since 1992, North American Moravians and Lutherans have been in dialogue about what it means to be churches seeking unity under one Lord and Savior. In 1998 and 1999, the Moravian Church Northern and Southern Provinces, and the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America, voted to establish a relationship of full communion. This relationship would recognize a mutual commitment to faith, practice, the nature of baptism, and the Lord’s Supper. Since 1999, these denominations have made visible commitments to evangelism, witness, and service, and work hard to keep one another informed about decisions around faith and life. As a result of this full communion relationship, Moravians and Lutherans listen to one another in decision-making and encourage ordained ministers to serve in each other’s churches. This summary, One Flock, One Shepherd: Lutheran-Moravian Relations, promotes further conversation and relations between Lutherans and Moravians. In 2007, the Eastern West Indies Moravian Province joined in full communion along with Moravians and Lutherans in North America. Likewise, an invitation was extended to the Moravian Alaskan Province to join as well. I. Looking Back: The Lutheran-Moravian Relationship: While we have been close to each other geographically, ethnically and theologically, Lutheran and Moravian churches in North America proceeded on separate denominational tracks. European and Native American influences in culture, tradition, and perspective, are mutually enriching for the entire life of the church. Jan Hus and the Bohemian Brethren, on the Moravian side, organized themselves as the Unitas Fratrum, preparing the ground for Martin Luther’s German Reformation. -

Early Moravian Pietism

EARLY MORAVIAN PIETISM BY MILTON C. WESTPHAL Lansdowne, Pennsylvania T HE visitor to the modern steel-town of Bethlehem, Penn- Tsylvania, is impressed with the noise and bustle of a com- munity which never would be suspected of having a distinctly spiritual origin. He might easily pass by the group of stone buildings on Church Street, which once housed the stalwart ad- herents of the Moravian Pilgrim Congregation, without noting that the historic edifices are essentially different from the many other closely built dwellings and business structures which en- croach upon them. Yet within the walls of these venerable piles were enacted scenes whose romance and passion have never yet been adequately appraised for their significance in the vari- colored history of American Protestantism. Even the townspeople of Bethlehem are almost entirely oblivi- ous of the fact that the name "Moravian Brethren" is one by which to conjure up a noteworthy succession of valiant religious characters, whose heroic deeds and pious strivings are still to be celebrated in an epic of the love of the Brethren for "The Christ of the Many Wounds." To be sure some of the remnants of the early fervor of the Moravian Church still remain to impress themselves upon the work-a-day minds of modern Bethlehemites, but American Moravianism has undergone a radical transforma- tion. The former holiness and the communal economy of that exclusive brotherhood have been surrendered. The fervent pietistic spirit, which prevailed when foot-washing and the "kiss of peace" were characteristic symbols, now lingers only as a pass- ing memory.