Vital Signs the Intersection of Health & Community Development

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Costume Crafts an Exploration Through Production Experience Michelle L

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Master's Theses Graduate School 2010 Costume crafts an exploration through production experience Michelle L. Hathaway Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses Part of the Theatre and Performance Studies Commons Recommended Citation Hathaway, Michelle L., "Costume crafts na exploration through production experience" (2010). LSU Master's Theses. 2152. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses/2152 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Master's Theses by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. COSTUME CRAFTS AN EXPLORATION THROUGH PRODUCTION EXPERIENCE A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts in The Department of Theatre by Michelle L. Hathaway B.A., University of Colorado at Denver, 1993 May 2010 Acknowledgments First, I would like to thank my family for their constant unfailing support. In particular Brinna and Audrey, girls you inspire me to greatness everyday. Great thanks to my sister Audrey Hathaway-Czapp for her personal sacrifice in both time and energy to not only help me get through the MFA program but also for her fabulous photographic skills, which are included in this thesis. I offer a huge thank you to my Mom for her support and love. -

Studying Craft: Trends in Craft Education and Training Participation in Contemporary Craft Education and Training

Studying craft: trends in craft education and training Participation in contemporary craft education and training Cover Photography Credits: Clockwise from the top: Glassmaker Michael Ruh in his studio, London, December 2013 © Sophie Mutevelian Head of Art Andrew Pearson teaches pupils at Christ the King Catholic Maths and Computing College, Preston Cluster, Firing Up, Year One. © University of Central Lancashire. Silversmith Ndidi Ekubia in her studio at Cockpit Arts, London, December 2013 © Sophie Mutevelian ii ii Participation in contemporary craft education and training Contents 1. GLOSSARY 3 2. FOREWORD 4 3. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 5 3.1 INTRODUCTION 5 3.2 THE OFFER AND TAKE-UP 5 3.3 GENDER 10 3.4 KEY ISSUES 10 3.5 NEXT STEPS 11 4. INTRODUCTION 12 4.1 SCOPE 13 4.2 DEFINITIONS 13 4.3 APPROACH 14 5. POLICY TIMELINE 16 6. CRAFT EDUCATION AND TRAINING: PROVISION AND PARTICIPATION 17 6.1 14–16 YEARS: KEY STAGE 4 17 6.2 16–18 YEARS: KEY STAGE 5 / FE 22 6.3 ADULTS: GENERAL FE 30 6.4 ADULTS: EMPLOYER-RELATED FE 35 6.5 APPRENTICESHIPS 37 6.6 HIGHER EDUCATION 39 6.7 COMMUNITY LEARNING 52 7. CONCLUDING REMARKS 56 8. APPENDIX: METHODOLOGY 57 9. NOTES 61 1 Participation in contemporary craft education and training The Crafts Council is the national development agency for contemporary craft. Our goal is to make the UK the best place to make, see, collect and learn about contemporary craft. www.craftscouncil.org.uk TBR is an economic development and research consultancy with niche skills in understanding the dynamics of local, regional and national economies, sectors, clusters and markets. -

Recipes Your Best Pies 39 Focus on Texas Photo Contest: Swings 40 Around Texas List of Local Events 42 Hit the Road Taking in Tyler by Melissa Gaskill

LOCAL ELECTRIC COOPERATIVE EDITION APRIL 2016 Helping Local Libraries Gettysburg Casualty Best Pies. Yum! HATSON! Texas hatmakers have you covered We’re e on a mission to set the neighborhood standard. With the most dependable equipment, we create spectacular spaces. We thrive on the fresh air, the challenge and the results of our efforts. We set the bar high to create a space we’re proud to call our own. kubota.com © Kubota Tractorr Corpporation, 2016 Since 1944 April 2016 FAVORITES 5 Letters 6 Currents 20 Local Co-op News Get the latest information plus energy and safety tips from your cooperative. 33 Texas History Gettysburg’s Last Casualty By E.R. Bills 35 Recipes Your Best Pies 39 Focus on Texas Photo Contest: Swings 40 Around Texas List of Local Events 42 Hit the Road Taking in Tyler By Melissa Gaskill Jeff Biggars applies steam ONLINE as he shapes a hat. TexasCoopPower.com Find these stories online if they don’t FEATURES appear in your edition of the magazine. Observations Cowboy Hatters Texas artisans crown your cranium in Tough Kid, Tough Breaks 8 a grand and storied tradition By Clay Coppedge Story by Gene Fowler | Photos by Tadd Myers Texas USA The Erudite Ranger Community Anchors Enlivening libraries establishes By Lonn Taylor 12 an environment for learning, sharing and loving literacy By Dan Oko NEXT MONTH New Directions in Farming A younger generation seeks alternatives to keep the family business thriving. 33 39 35 42 BIGGARS: TADD MYERS. PLANT: CANDY1812 | DOLLAR PHOTO CLUB ON THE COVER J.W. Brooks handcrafts hats for cowboys and cowgirls at his shop in Lipan. -

The Milliner Cross Stitch Pattern by Perrette Samouiloff

The Milliner cross stitch pattern by Perrette Samouiloff Manufacturer: Perrette Samouiloff Reference:PER239 Price: $11.99 Options: download pdf file : English Description: The Milliner CROSS STITCH PATTERN READY TO DOWNLOAD, DESIGNED BY Perrette Samouiloff This design is part of a series of cross stitch charts related to needlecrafts. After the Lacemaker, here is a tribute to the fine art of hatmaking. The milliner's trade, which has almost disappeared today, is the art of designing, making, decorating and personalizing hats, fashion accessories par excellence. In this cross stitch pattern, the milliner is at work, needle in hand, in her hat shop, while her customers try various hats on. The hats come in a wide variety of styles and very feminine shapes: wide brim and veil, cloche hats from the thirties, floppy brimmed hats, round caps, straw hats, together with a whole collection of exquisite small hat pins. The title of the embroidery "The Milliner" is embroidered in pretty cursive letters. The design is an adaptation from the French "La Modiste". If you would rather stitch the French version, please contact us after placing the order and we will send you the chart with the original French text (last picture). A cross stitch pattern by Perrette Samouiloff. >> see more patterns related to Fashion and Costumes by Perrette Samouiloff Chart info & Needlework supplies for the pattern: The Milliner Chart size in stitches: 138 x 160(wide x high) Needlework fabric: Aida, Linen or Evenweave, white >> View size in my choice of fabric (fabric calculator) Stitches: Cross stitch, Backstitch, 3/4 cross stitch Chart: Black & White, color detail Threads: DMC Number of colors:1 Themes: hat making workshop, hat shop, fashion, ornamental hat pins >> see all patterns related to Clothes and Fashion accessories (all designers) All patterns on Creative Poppy's website are printable and available for instant download. -

Color Front Cover

COLOR FRONT COVER COLOR CGOTH IS I COLOR CGOTH IS II COLOR CONCERT SERIES Welcome to our 18th Season! In this catalog you will find a year's worth of activities that will enrich your life. Common Ground on the Hill is a traditional, roots-based music and arts organization founded in 1994, offering quality learning experiences with master musicians, artists, dancers, writers, filmmakers and educators while exploring cultural diversity in search of a common ground among ethnic, gender, age, and racial groups. The Baltimore Sun has compared Common Ground on the Hill to the Chautauqua and Lyceum movements, precursors to this exciting program. Our world is one of immense diversity. As we explore and celebrate this diversity, we find that what we have in common with one another far outweighs our differences. Our common ground is our humanity, often best expressed by artistic traditions that have enriched human experience through the ages. We invite you to join us in searching for common ground as we assemble around the belief that we can improve ourselves and our world by searching for the common ground in one another, through our artistic traditions. In a world filled with divisive, negative news, we seek to discover, create and celebrate good news. How we have grown! Common Ground on the Hill is a multifaceted year-round program, including two separate Traditions Weeks of summer classes, concerts and activities, held on the campus of McDaniel College, two separate Music and Arts festivals held at the Carroll County Farm Museum, two seven-event Monthly Concert Series held in Westminster and Baltimore, and a new program this summer at the Lutheran Theological Seminary at Gettysburg, Common Ground on Seminary Ridge. -

Tela Ecólogica Textile Traditions + Eco-Tourism in Yucatán --- 2017 International Textile + Apparel Association Study Tour

Tela Ecólogica Textile Traditions + Eco-Tourism in Yucatán --- 2017 International Textile + Apparel Association Study Tour --- Date December 9-20, 2017 Duration 12 days Cost $2,500 USD per person OVERVIEW Tela Ecólogica is a textile-focused cultural and creative immersion experience into the world of Mexican artisanship, craft processes and design. This study opportunity offers exposure to new cultural environments and insight into the world of artisan production as it applies to the Yucatán region and its people. It will foster a deeper understanding of the impacts of globalization on Mayan culture, and the significance of environmental stewardship and social justice through the lens of cultural textiles and craft. Yucatán is wonderfully rich with the cultural context of language, food, and visual aesthetics. Participants will experience travel in the region from a range of different vantage points- from tourist resorts, historic boutique hotels to thatched roof huts. We will stay in haciendas, swim in cenotes, and visit ancient Maya ruins. We will tour the popular cities of Cancun, Tulum and Playa del Carmen, and visit the lesser-travelled cities of Merida and Valladolid, and experience many charming pueblos along the way. Participants will get a rarely-seen glimpse of authentic textile design and craft making throughout the the Yucatán peninsula region, experiencing the beauty of Mexican culture as we tour marketplaces, textile factories, ateliers, boutiques, artist studios, designer workshops, artisan homes and museums. We will learn regional handcraft skills from indigenous Mayan artisans and designers- exploring henequen fiber processing, back-strap loom weaving, hand and machine embroidery, cross-stitch, crochet and natural dyeing, completing our own sample works along the way. -

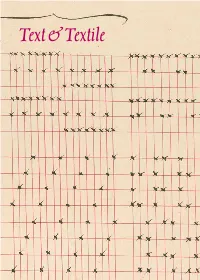

Text &Textile Text & Textile

1 TextText && TextileTextile 2 1 Text & Textile Kathryn James Curator of Early Modern Books & Manuscripts and the Osborn Collection, Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library Melina Moe Research Affiliate, Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library Katie Trumpener Emily Sanford Professor of Comparative Literature and English, Yale University 3 May–12 August 2018 Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library Yale University 4 Contents 7 Acknowledgments 9 Introduction Kathryn James 13 Tight Braids, Tough Fabrics, Delicate Webs, & the Finest Thread Melina Moe 31 Threads of Life: Textile Rituals & Independent Embroidery Katie Trumpener 51 A Thin Thread Kathryn James 63 Notes 67 Exhibition Checklist Fig. 1. Fabric sample (detail) from Die Indigosole auf dem Gebiete der Zeugdruckerei (Germany: IG Farben, between 1930 and 1939[?]). 2017 +304 6 Acknowledgments Then Pelle went to his other grandmother and said, Our thanks go to our colleagues in Yale “Granny dear, could you please spin this wool into University Library’s Special Collections yarn for me?” Conservation Department, who bring such Elsa Beskow, Pelle’s New Suit (1912) expertise and care to their work and from whom we learn so much. Particular thanks Like Pelle’s new suit, this exhibition is the work are due to Marie-France Lemay, Frances of many people. We would like to acknowl- Osugi, and Paula Zyats. We would like to edge the contributions of the many institu- thank the staff of the Beinecke’s Access tions and individuals who made Text and Textile Services Department and Digital Services possible. The Yale University Art Gallery, Yale Unit, and in particular Bob Halloran, Rebecca Center for British Art, and Manuscripts and Hirsch, and John Monahan, who so graciously Archives Department of the Yale University undertook the tremendous amount of work Library generously allowed us to borrow from that this exhibition required. -

(A) Machinery, Plant, Vehicles ; (B) Construction of Buildings ; Basic Data on the Essential Characteristics of Industry Were Co

Official Journal of the European Communities 201 13.8.64 OFFICIAL JOURNAL OF THE EUROPEAN COMMUNITIES 2193/64 COUNCIL DIRECTIVE of 30 July 1964 concerning co-ordinated annual surveys of investment in industry ( 64/475/EEC ) THE COUNCIL OF THE EUROPEAN ECONOMIC Article 2 COMMUNITY, For the purposes of this Directive, an industry shall Having regard to the Treaty establishing the Euro be defined by reference to the 'Nomenclature of Indus pean Economic Community, and in particular Article tries in the European Communities' ( NICE). 1 In the 213 thereof ; case of small undertakings the survey may be carried out by random sampling. Having regard to the draft submitted by the Com Article 3 Whereas in order to carry out the tasks entrusted to it under the Treaty the Commission must have at its The figures to be recorded shall be those in respect disposal annual statistics on the trend of investment of annual investment expenditure ( including plant in the industries of the Community ; constructed by the undertakings themselves), broken Whereas in the industrial survey for 1962 comparable down as follows : basic data on the essential characteristics of industry ( a ) Machinery, plant, vehicles ; were collected for the first time ; whereas such a ( b) Construction of buildings ; census cannot be carried out frequently ; whereas annual statistics concerning certain basic matters ( c) Purchase of existing buildings and of land . cannot however be dispensed with for the intervening Investments of a social nature shall , where possible, be years -

An Illustrated Guide to Hatmaking Denise Dreher

From The Neck Up: An Illustrated Guide To Hatmaking Denise Dreher - free pdf download free online From the Neck Up: An Illustrated Guide to Hatmaking, PDF From the Neck Up: An Illustrated Guide to Hatmaking Popular Download, Denise Dreher epub From the Neck Up: An Illustrated Guide to Hatmaking, Denise Dreher epub From the Neck Up: An Illustrated Guide to Hatmaking, PDF Download From the Neck Up: An Illustrated Guide to Hatmaking Free Collection, From the Neck Up: An Illustrated Guide to Hatmaking Ebook Download, From the Neck Up: An Illustrated Guide to Hatmaking Free Read Online, Download PDF From the Neck Up: An Illustrated Guide to Hatmaking, Denise Dreher ebook From the Neck Up: An Illustrated Guide to Hatmaking, From the Neck Up: An Illustrated Guide to Hatmaking Book Download, From the Neck Up: An Illustrated Guide to Hatmaking Ebooks Free, pdf Denise Dreher From the Neck Up: An Illustrated Guide to Hatmaking, Download pdf From the Neck Up: An Illustrated Guide to Hatmaking, Read From the Neck Up: An Illustrated Guide to Hatmaking Online Free, PDF From the Neck Up: An Illustrated Guide to Hatmaking Full Collection, PDF From the Neck Up: An Illustrated Guide to Hatmaking Popular Download, From the Neck Up: An Illustrated Guide to Hatmaking pdf read online, pdf Denise Dreher From the Neck Up: An Illustrated Guide to Hatmaking, Free Download From the Neck Up: An Illustrated Guide to Hatmaking Full Popular Denise Dreher, From the Neck Up: An Illustrated Guide to Hatmaking pdf read online, CLICK HERE - DOWNLOAD epub, mobi, azw, pdf Description: -

Pre-College Summer 2017.Indd

PRE-COLLEGEPRE-COLLEGE PROGRAMPROGRAM FUA FLORENCE UNIVERSITY OF THE ARTS Summer 2017 FFlorence,lorence, IItalytaly FUA PROGRAM OVERVIEW FUA Florence University of the Arts is offering a unique opportunity for high school students to participate in its cultural and academic offering. During the 3 or 4-week program, students can earn college credit, selecting from an exciting range of courses held at FUA’s academic campuses located in the historic center of Florence. Courses are designed to prepare students for college entrance and the transfer of credit, whilst participation in field learning and extra-curricular activities will engage and immerse students in the Italian culture. STUDYING IN FLORENCE PROGRAM DETAILS As the place that fostered the birth of Renaissance art, literature, philosophy and This program is aimed at students wishing to design their own intellectual thought, the home of world famous cuisine and of fashion greats, Italy curriculum prior to college entrance. Students may opt for a 3 or is the ideal place to study. Perhaps nowhere else than Tuscany can such a multitude 4-week program. The 4-week program begins with a week of Cultural of artistic, cu ltural and historic resources be found; situated in the true heart of Introduction to Italy field learning experience in various locations the country, the region has everything to offer, from medieval hill-top hamlets to prior to the 3 weeks of coursework in Florence. All 3 and 4-week bustling port cities, snow-capped mountains, and miles of beaches. students select two courses from the offered curriculum at the FUA campus in Florence. -

Francisco Rico Vanessa Coley the Hat Stand Pinokpok and More... the E-Magazine for Those Who Make Hats Issue 125 August 2016 Contents

Issue 125 August 2016 Francisco Rico Vanessa Coley The Hat Stand Pinokpok and more... the e-magazine for those who make hats Issue 125 August 2016 Contents: Francisco Rico 2 Meet one of London's hottest new designers - maker of will.i.am's Met Gala hat. Hat of the Month 6 A veiled mini topper by Vanessa Coley. The Hat Stand 11 The Sheffield pop-up returns as a testament to the power of teamwork. Know Your Millinery Materials 15 LilyM Millinery Supplies show us how pinokpok is made. Letter to the Editor 18 Using leather in millinery. The Back Page 19 A South American hat competition and how to contact us. Cover/Back Page: Images by Ellie Grace Photography Hats by Imogen’s Imagination and Amanda Moon Headwear 1 www.hatalk.com FRANCISCO RICO 2 www.hatalk.com Francisco Rico was born and raised move to London in 2012 to pursue working for him. He creates two in Seville, Spain. After spending his new passion - designing and couture hat collections a year, as well several years undertaking business producing hats. Since then, he has as concept collections and private studies and working in management studied under royal milliner Rose commissions. He has worked on and development for a number of Cory, taken classes at Central Saint pieces for some very high profile international companies, Francisco Martins and completed the HND clients, including a recent project for stumbled upon the world of hats Millinery programme at Kensington recording artist will.i.am. in Madrid and realised that he had and Chelsea College. -

SUMMER 2018 HIGH SCHOOL PROGRAMS About SAI SAI High School Summer Program

SUMMER 2018 HIGH SCHOOL PROGRAMS About SAI SAI High School Summer Program Since 1995, SAI has provided students with exceptional cultural and educational in Florence, Italy experiences abroad, offering the opportunity to enroll in some of the finest SAI and Florence University of the Arts (FUA) are pleased to offer high school schools available to English speaking students in Europe. By encouraging students from all academic backgrounds the possibility to enroll in college-level students to explore the complex intersections between self, community, and courses while nurturing their knowledge and talents in a safe and supportive creativity, SAI aims to provide an inspiring and transformative experience for all environment. Courses are supplemented by hands-on activities: excursions to participants. All of SAI’s services, in the U.S. and overseas, are geared toward important centers of Italian art and culture; design and studio art classes supported ensuring student safety and maximizing the student experience; both in terms by state-of-the-art facilities; cooking classes in professional kitchens; and fun of providing a framework for academic inquiry, and offering each student sporting activities. In addition, Italian language courses offer beginning-level opportunities for personal growth and development. students the tools to communicate in everyday life while taking advantage of the city of Florence as a classroom. We pride ourselves on our guiding principles: SAI offers a 3 week and 4 week option, in which students earn 6 or 9 college Personal attention We build relationships with our students • credits while living in one of the most treasured centers of art, culture and history throughout the study abroad experience.