Lost Roads on Hexham Fell

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Map for Day out One Hadrian's Wall Classic

Welcome to Hadian’s Wall Country a UNESCO Arriva & Stagecoach KEY Map for Day Out One World Heritage Site. Truly immerse yourself in Newcastle - Hexham - Carlisle www.arrivabus.co.uk/north-east A Runs Daily the history and heritage of the area by exploring 685 Hadrian’s Wall Classic Tickets and Passes National Trail (See overleaf) by bus and on foot. Plus, spending just one day Arriva Cuddy’s Crags Newcastle - Corbridge - Hexham www.arrivabus.co.uk/north-east Alternative - Roman Traveller’s Guide without your car can help to look after this area of X85 Runs Monday - Friday Military Way (Nov-Mar) national heritage. Hotbank Crags 3 AD122 Rover Tickets The Sill Walk In this guide to estbound These tickets offer This traveller’s guide is designed to help you leave Milecastle 37 Housesteads eet W unlimited travel on Parking est End een Hadrian’s Wall uns r the AD122 service. Roman Fort the confines of your car behind and truly “walk G ee T ont Str ough , Hexham Road Approx Refreshments in the footsteps of the Romans”. So, find your , Lion and Lamb journey times Crag Lough independent spirit and let the journey become part ockley don Mill, Bowes Hotel eenhead, Bypass arwick Bridge Eldon SquaLemingtonre Thr Road EndsHeddon, ThHorsler y Ovington Corbridge,Road EndHexham Angel InnHaydon Bridge,Bar W Melkridge,Haltwhistle, The Gr MarketBrampton, Place W Fr Scotby Carlisle Adult Child Concession Family Roman Site Milecastle 38 Country Both 685 and X85 of your adventure. hr Sycamore 685 only 1 Day Ticket £12.50 £6.50 £9.50 £26.00 Haydon t 16 23 27 -

Norman Rule Cumbria 1 0

NORMAN RULE I N C U M B R I A 1 0 9 2 – 1 1 3 6 B y RICHARD SHARPE A lecture delivered to Cumberland and Westmorland Antiquarian and Archaeological Society on 9th April 2005 at Carlisle CUMBERLAND AND WESTMORLAND ANTIQUARIAN AND ARCHAEOLOGICAL SOCIETY N O R M A N R U L E I N C U M B R I A 1 0 9 2 – 1 1 3 6 NORMAN RULE I N C U M B R I A 1 0 9 2 – 1 1 3 6 B y RICHARD SHARPE Pr o f essor of Diplomat i c , U n i v e r sity of Oxfo r d President of the Surtees Society A lecture delivered to Cumberland and Westmorland Antiquarian and Archaeological Society on 9th April 2005 at Carlisle CUMBERLAND AND WESTMORLAND ANTIQUARIAN AND ARCHAEOLOGICAL SOCIETY Tract Series Vol. XXI C&W TRACT SERIES No. XXI ISBN 1 873124 43 0 Published 2006 Acknowledgements I am grateful to the Council of the Society for inviting me, as president of the Surtees Society, to address the Annual General Meeting in Carlisle on 9 April 2005. Several of those who heard the paper on that occasion have also read the full text and allowed me to benefit from their comments; my thanks to Keith Stringer, John Todd, and Angus Winchester. I am particularly indebted to Hugh Doherty for much discussion during the preparation of this paper and for several references that I should otherwise have missed. In particular he should be credited with rediscovering the writ-charter of Henry I cited in n. -

Assessing the Past the Following List Contains Details of Archaeological

Assessing the Past The following list contains details of archaeological assessments, evaluations and other work carried out in Northumberland in 2013-2015. They mostly result from requests made by the County Archaeologist for further research to be carried out ahead of planning applications being determined. Copies of these reports are available for consultation from the Archaeology Section at County Hall and some are available to download from the Library of Unpublished Fieldwork held by the Archaeology Data Service. Event Site Name Activity Organisation Commissioned by Start Parish No 15115 East House Farm, Guyzance, DESK BASED Wessex Archaeology Knight Frank LLP 2013 ACKLINGTON Northumberland: Archaeological Impact ASSESSMENT Assessment 15540 Lanton Quarry Phase 6 archaeological STRIP MAP AND Archaeological Lafarge Tarmac Ltd 2013 AKELD excavation SAMPLE Research Services 15340 Highburn House, Wooler WATCHING BRIEF Archaeological Services Sustainable Energy 2013 AKELD Durham University Systems Ltd 15740 Archaeological assessment of Allenheads DESK BASED Vindomora Solutions The North Pennines 2013 ALLENDALE Lead Ore Works and associated structures, ASSESSMENT AONB Partnership as Craigshield Powder House, Allendale part of the HLF funded Allen Valleys Partnership Project 15177 The Dale Hotel, Market Place, Allendale, EVALUATION Wardell Armstrong Countryside Consultants 2013 ALLENDALE Northumberland: archaeological evaluation 15166 An Archaeological Evaluation at Haggerston TRIAL TRENCH Pre-Construct Prospect Archaeology 2013 ANCROFT -

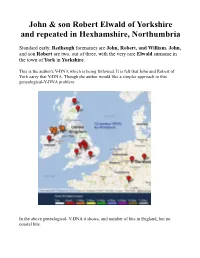

John & Son Robert Elwald of Yorkshire and Repeated in Hexhamshire

John & son Robert Elwald of Yorkshire and repeated in Hexhamshire, Northumbria Standard early, Redheugh forenames are John, Robert, and William. John, and son Robert are two, out of three, with the very rare Elwald surname in the town of York in Yorkshire. This is the author's Y-DNA which is being followed. It is felt that John and Robert of York carry that Y-DNA. Though the author would like a simpler approach to this genealogical-Y-DNA problem. In the above genealogical- Y-DNA it shows, and number of hits in England, but no coastal hits. It should be noted that York is near Wolds (woods), as apposed to the Moors (moorland). Note the location of Scarborough; Hexham north part of map. The first name translated as Johannes (John), and the middle name Johannesen (Johnson (son of John)). So it is in Norway, the name John was held in high, and also surname Walde, for Elwalde is importand. Both German and Danish seem to prefix wald (woods). Elwald surname emerged not as a location such as Scarborough, but as being the son of (fitz) Elwald. It is felt that John and his son Robert could easily carry similar Y- DNA out of the Northumberland, region of York. As one can see above Johannes Elwald mercator quam. This shows, how both Johnannes and Elwald could have strong origins in Denmark German. The name Robert had strong influence after 1320 because of Robert the Bruce, who the Elwald fought for in the separation of the crowns of Scotland and England. -

The Forts on Hadrian S Wall: a Comparative Analysis of the Form and Construction of Some Buildings

Durham E-Theses The forts on Hadrian s wall: a comparative analysis of the form and construction of some buildings Taylor, David J.A. How to cite: Taylor, David J.A. (1999) The forts on Hadrian s wall: a comparative analysis of the form and construction of some buildings, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/4555/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 The forts on Hadrian's Wall: a comparative analysis of the form and construction of some buildings in three volumes David J. A. Taylor 19 JUL Volume 1 The copyright of this thesis rests witli tlie author. No quotation from it should be published widiout the written consent of the author and information derived from it should be acknowledged. A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Archaeology, University of Durham, 1999 I confirm that no part of the material offered has previously been submitted by me for a degree in this or in any other University. -

Hadrian's Wall 1999-2009

HADRIAN’S WALL 1999-2009 HADRIAN’S WALL HADRIAN’S WALL 1999-2009 A summary of recent excavation and research prepared for the Thirteenth Pilgrimage of Hadrian’s Wall, 2009 HADRIAN’S WALL 1999-2009 The Pilgrimage of Hadrian’s Wall (a tradition going back to 1849) takes place every ten years, giving all who are interested in the remains of Rome’s most elaborate frontier a chance to revisit the remains and hear about the latest archaeological developments. This specially prepared book, with contributions from all the major excavators on the Wall, describes research and discovery that has taken place since the last pilgrimage in 1999. This has been an extraordinary decade for Wall-research, featuring the discovery of the probable ancient name for the barrier, and the recognition Compiled by N. Hodgson of a previously unknown element of its anatomy (obstacles in front of the Wall), which is the rst such addition to our image of the Wall in modern times. This book explains where the new information is to be found, and will appeal to all who visit or study Hadrian’s remarkable frontier. CUMBERLAND & WESTMORLAND ANTIQUARIAN AND ARCHAEOLOGICAL SOCIETY THE SOCIETY OF ANTIQUARIES OF NEWCASTLE UPON TYNE Compiled by N. Hodgson Front cover: the Staffordshire Moorlands Pan, inscribed with the names of Wall- forts and the probable ancient name of the Wall (courtesy of Portable Antiquities Scheme) Back cover: emplacements for obstacles between the Wall and its ditch, under excavation at Byker, Newcastle upon Tyne 551114_TWM_COVER.indd1114_TWM_COVER.indd 1 117/07/20097/07/2009 009:319:31 CUMBERLAND AND WESTMORLAND ANTIQUARIAN AND ARCHAEOLOGICAL SOCIETY THE SOCIETY OF ANTIQUARIES OF NEWCASTLE UPON TYNE HADRIAN’S WALL 1999-2009 A Summary of Excavation and Research prepared for The Thirteenth Pilgrimage of Hadrian’s Wall, 8-14 August 2009 compiled by N. -

Spring: Download

HEXHAM LOCAL HISTORY SOCIETY Newsletter 59 Spring 2011 Still waiting for volunteers – one will do! If you fancy a go, I’ll be more than Editor happy to walk you through compiling the next issue, due out in the summer. sought Hope to hear from someone soon on [email protected] ! I’d like to thank all members who have paid or renewed their subscriptions Message promptly – and to gently remind those of you who have yet to get around to it! from the Subscription rates remain unchanged and, as I’m sure you’ll agree, are Secretary excellent value for money. Yvonne Purdy Next month sees the 250th anniversary of the Hexham Militia Riot, when The Hexham troops opened fire on crowds protesting against balloting for militia conscription Riot on Monday 9th March 1761. Those who have read Tom Corfe’s excellent Liz Sobell & account of the riot (2004) will know just what shock and distress must have Jim Hedley been caused in Hexham and the surrounding area when news of the 52 dead and hundreds injured swept through the district. All the more surprising, then, is this letter written about a missed breakfast meeting just two days later, when in the Market Place the blood of the dead and injured had barely washed away. It was written by Robert Lowes, aged 54, an attorney in Hexham and member of the well-connected family of Lowes of Ridley Hall near Haltwhistle. His house, later the Post Office and now known as Hadrian House, was just off the Market Place. -

Housesteads Roman Fort to Chesters Roman Fort and Museum Northumberland

Housesteads Roman Fort to Chesters Roman Fort and Museum Northumberland 8 Limestone 9 7 Corner Carrawburgh Black Carts Turret 5 Roman Fort Grindon 6 4 milecastle Sewingshields Wall 10 3 Busy Gap Chesters 2 Roman Fort Knag Burn Gateway 1 Housesteads Roman Fort 1000m 2000ft Survey Map: Ordnance Note: this map is intended as a guide only. We would always advise you to use these guides in conjunction with the OS maps referenced below. Please check the opening times of properties at www.english-heritage.org.uk before setting off. Need to know Directions OS reference: OS Explorer map OL43 1 The trail starts with a visit to Housesteads Roman Fort. From here, turn right and join Hadrian’s Wall Distance: 9.6 miles/15.5km (six hours) Path as it leaves the fort. Difficulty: 3/5 2 Continue east to Knag Burn Gateway, possibly an old Terrain: A moderate walk through woods and moorland with some stiles and clear customs post. The trail is clearly way marked with a waymarking field wall to the side. Access: This walk is not suitable for wheelchairs 3 Follow the wall and cross a stile to arrive at Busy Dog walking: This is a dog-friendly walk Gap, where a drove road ran north in later times. Refreshments: Drinks and food are available at Chesters Tearoom. Look out for A section of the original wall remains to the left. refreshments along the route – often at the car park near Carrawburgh Roman Fort 4 Head through the gate and follow the wall over a Sat nav: Starts Housesteads Roman Fort, Bardon Mill, Hexham NE47 6NN (01434 series of hills until you reach the trig point atop the 344363); ends Chesters Roman Fort, Chollerford, Hexham NE46 4EU crag at Sewingshields Wall with a lovely view of Broomlee Lough. -

Hexham Northumberland Extensive Urban Survey

Hexham Northumberland Extensive Urban Survey The Northumberland Extensive Urban Survey Project was carried out between 1995 and 2008 by Northumberland County Council with the support of English Heritage. © Northumberland County Council and English Heritage 2009 Produced by Rhona Finlayson, Richard Carlton and Caroline Hardie 1995-7 Revised by Alan Williams 2007-8 Strategic Summary by Karen Derham 2008 Planning policies revised 2010 All the mapping contained in this report is based upon the Ordnance Survey mapping with the permission of the Controller of Her Majesty's Stationary Office. © Crown copyright. All rights reserved 100049048 (2009) All historic mapping contained in this report is reproduced courtesy of the Northumberland Collections Service unless otherwise stated. Copies of this report and further information can be obtained from: Northumberland Conservation Development & Delivery Planning Economy & Housing Northumberland County Council County Hall Morpeth NE61 2EF Tel: 01670 620305 Email: [email protected] Website: http://www.northumberland.gov.uk/archaeology Hexham Extensive Urban Survey 1 CONTENTS PART ONE: THE STORY OF HEXHAM 1 INTRODUCTION 1.1 Project Background 1.2 Location, Geology and Topography 1.3 Brief History 1.4 Documentary and Secondary Sources 1.5 Cartographic Sources 1.6 Archaeological Sources 1.7 Protected Sites 2 PREHISTORIC AND ROMAN 2.1 The Prehistoric Period 2.2 The Roman Period 3 EARLY MEDIEVAL 3.1 The Churches 3.2 Graveyards 3.3 Secular Settlement 3.4 Communications 4 MEDIEVAL 4.1 Churches -

Enjoy a Great Walk Through Hadrian's Wall Country with the AD122 Bus

Enjoy a great walk through Hadrian’s Wall Country with the AD122 Bus The AD122, the Hadrian’s Wall Country Bus, makes it easy to explore our Roman heritage and get out and about in some of the country’s most spectacular landscapes. With eco-friendly buses, next stop announcements, stunning views and friendly drivers, the journey is part of the experience. Here are some suggestions for walks and visits either as a family, with friends or just with your own company ! You can download the walks (http://hadrianswallcountry.co.uk/walking/walking-routes) and the bus timetable (http://hadrianswallcountry.co.uk/travel/bus) from the official Hadrian’s Wall website. Chesters Fort and Humshaugh (start/finish at Chesters Fort - 15 minutes on the AD122 from Hexham): an easy two and a half walking mile route that will take about an hour. Refreshments at the Crown Inn, Humshaugh, the George Hotel in Chollerford or the refurbished tea rooms at Chesters Roman Fort. Include a visit to the Fort to see the newly updated information on site and in the charming and fascinating museum. Picnic by the banks of the Tyne where a Roman bridge once stood. A Barbarian View of the Wall (start/finish at Once Brewed/The Sill – 35 minutes on the AD122 from Hexham, 15 minutes from Haltwhistle station): a fairly strenuous three and a half mile walking route that will take about two hours, or a little more. The route follows the Hadrian’s Wall Path National Trail for part of the way, then takes you north into ‘Barbarian territory, giving you a different and spectacular view of the Wall snaking along the Crags to the south. -

Download Download

Bearsden A Roman Fort on the Antonine Wall David J Breeze ISBN: 978-1-908332-08-0 (hardback) • 978-1-908332-18-9 (PDF) The text in this work is published under a Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommerical 4.0 International licence (CC BY-NC 4.0). This licence allows you to share, copy, distribute and transmit the work and to adapt the work for non-commercial purposes, providing attribution is made to the authors (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work). Attribution should include the following information: Breeze, D J 2016 Bearsden: A Fort on the Antonine Wall. Edinburgh: Society of Antiquaries of Scotland. https://doi.org/10.9750/9781908332189 Important: The illustrations and figures in this work are not covered by the terms of the Creative Commons licence. Permissions must be obtained from third-party copyright holders to reproduce any of the illustrations. Every effort has been made to obtain permissions from the copyright holders of third-party material reproduced in this work. The Society of Antiquaries of Scotland would be grateful to hear of any errors or omissions. Society of Antiquaries of Scotland is a registered Scottish charity number SC 010440. Visit our website at www.socantscot.org or find us on Twitter @socantscot. BEARSDEN: A ROMAN FORT ON THE ANTONINE WALL bibliography bibliographY ABBREVIATIONS Allen, G 2004 ‘Roman Glass’, in Bishop, M C Inveresk Gate: Excavations in the Roman Civil Settlement at Inveresk, East Lothian, 1996–2000: AE l’anneé épigraphique 167–9. Loanhead: STAR. BMC British Museum Catalogue of Coins of the Roman Amrein H 2006 ‘Marques sur verre attestées en Suisse’, in Foy & Nenna Empire (eds) 2006b: 209–43. -

Contextualizing Hadrian's Wall

CONTEXTUALIZING HADRIAN’S WALL: THEWALLAS‘DEBATABLELANDS’ Richard Hingley and Rich Hartis . Introduction This article emphasizes the symbolic monumentality of Hadrian’s Wall, exploring the idea that it was a porous and contested frontier.1 There has been a recent outpouring of archaeological and management pub- lications on Hadrian’s Wall,2 which provide substantial new knowledge and improve our understanding of the structure. In light of the state-of- play with Wall studies today, our motivation here is twofold. Firstly, we aim to encourage the opening up research on Hadrian’s Wall to a broad series of questions deriving from studies of frontiers and borders in other cultural contexts.3 There are many new approaches to contemporary and historic borderlands and frontiers, stemming from geography, history, cultural studies and English literature, and we wish to promote a broad comparative approach to Roman frontiers that draws upon this wider frontier-research.4 Secondly, our approach draws upon recent writings that formulate new approaches to Roman identities and social change,5 1 R. Hingley, ‘Tales of the Frontier: diasporas on Hadrian’s Wall’, in H. Eckardt (ed.), Roman Diasporas (Portsmouth, ). 2 For examples, P. Bidwell, Understanding Hadrian’s Wall (Kendal ); D. Breeze, J. Collingwood Bruce’s Handbook to the Roman Wall (Newcastle upon Tyne , th ed.); A. Rushworth, Housesteads Roman Fort—The Grandest Station (London ); M.F.A. Symonds—D.J.P.Mason, Frontiers of Knowledge: A Research Framework for Hadri- an’s Wall (Durham ). 3 See S. James, ‘Limsefreunde in Philadelphia: a snapshot of the state of Roman Frontier Studies’, Britannia (), – and R.