Hexham Northumberland Extensive Urban Survey

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fantastic W Ays to Travel and Save Money with Go North East Travelling with Uscouldn't Be Simpler! Ten Services Betw Een

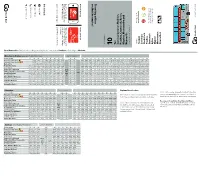

money with Go North East money and save travel to ways Fantastic couldn’t be simpler! couldn’t with us Travelling gonortheast.co.uk the Go North East app. mobile with your to straight times and tickets Live Go North app East Get in touch gonortheast.co.uk 420 5050 0191 @gonortheast simplyGNE 5 mins 5 mins gonortheast.co.uk /gneapp Buses run up to Buses run up to 30 minutes every ramp access find You’ll bus and travel on every on board. advice safety gonortheast.co.uk smartcard. deals on exclusive with everyone, easier for cheaper and travel Makes smartcard the key /thekey the key the key Serving: Hexham Corbridge Stocksfield Prudhoe Crawcrook Ryton Blaydon Metrocentre Newcastle Go North East 10 Bus times from 21 May 2017 21 May Bus times from Ten Ten Hexham, between Services Ryton, Crawcrook, Prudhoe, and Metrocentre Blaydon, Newcastle 10 — Newcastle » Metrocentre » Blaydon » Ryton » Crawcrook » Prudhoe » Corbridge » Hexham Mondays to Fridays (except Public Holidays) Every 30 minutes at Service number 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10X 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 Newcastle Eldon Square - 0623 0645 0715 0745 0815 0855 0925 0955 25 55 1355 1425 1455 1527 1559 1635 1707 1724 1740 1810 1840 1900 1934 1958 2100 2200 2300 Newcastle Central Station - 0628 0651 0721 0751 0821 0901 0931 1001 31 01 1401 1431 1501 1533 1606 1642 1714 1731 1747 1817 1846 1906 1940 2003 2105 2205 2305 Metrocentre - 0638 0703 0733 0803 0833 0913 0944 1014 44 14 1414 1444 1514 1546 1619 1655 1727 X 1800 1829 1858 1919 1952 2016 2118 2218 2318 Blaydon -

Norman Rule Cumbria 1 0

NORMAN RULE I N C U M B R I A 1 0 9 2 – 1 1 3 6 B y RICHARD SHARPE A lecture delivered to Cumberland and Westmorland Antiquarian and Archaeological Society on 9th April 2005 at Carlisle CUMBERLAND AND WESTMORLAND ANTIQUARIAN AND ARCHAEOLOGICAL SOCIETY N O R M A N R U L E I N C U M B R I A 1 0 9 2 – 1 1 3 6 NORMAN RULE I N C U M B R I A 1 0 9 2 – 1 1 3 6 B y RICHARD SHARPE Pr o f essor of Diplomat i c , U n i v e r sity of Oxfo r d President of the Surtees Society A lecture delivered to Cumberland and Westmorland Antiquarian and Archaeological Society on 9th April 2005 at Carlisle CUMBERLAND AND WESTMORLAND ANTIQUARIAN AND ARCHAEOLOGICAL SOCIETY Tract Series Vol. XXI C&W TRACT SERIES No. XXI ISBN 1 873124 43 0 Published 2006 Acknowledgements I am grateful to the Council of the Society for inviting me, as president of the Surtees Society, to address the Annual General Meeting in Carlisle on 9 April 2005. Several of those who heard the paper on that occasion have also read the full text and allowed me to benefit from their comments; my thanks to Keith Stringer, John Todd, and Angus Winchester. I am particularly indebted to Hugh Doherty for much discussion during the preparation of this paper and for several references that I should otherwise have missed. In particular he should be credited with rediscovering the writ-charter of Henry I cited in n. -

Weekly List of Planning Applications

Northumberland County Council Weekly List of Planning Applications Applications can view the document online at http://publicaccess.northumberland.gov.uk/online-applications If you wish to make any representation concerning an application, you can do so in writing to the above address or alternatively to [email protected]. Any comments should include a contact address. Any observations you do submit will be made available for public inspection when requested in accordance with the Access to Information Act 1985. If you have objected to a householder planning application, in the event of an appeal that proceeds by way of the expedited procedure, any representations that you made about the application will be passed to the Secretary of State as part of the appeal Application No: 19/03064/FUL Expected Decision: Delegated Decision Date Valid: Sept. 9, 2019 Applicant: Mr Daniel Kemp Agent: Mr Adam Barrass Keepwick Farm, Humshaugh, 16/17 Castle Bank, Tow Law, Hexham, Bishop Auckland, DL13 4AE, Proposal: Proposal for the construction of a four bedroomed agricultural workers dwelling adjacent to existing agricultural building Location: Land North West Of Carterway Heads, Carterway Heads, Northumberland Neighbour Expiry Date: Sept. 9, 2019 Expiry Date: Nov. 3, 2019 Case Officer: Ms Melanie Francis Decision Level: Ward: South Tynedale Parish: Shotley Low Quarter Application No: 19/03769/FUL Expected Decision: Delegated Decision Date Valid: Sept. 9, 2019 Applicant: Mr & Mrs Glenn Holliday Agent: Earle Hall 12 Birney Edge, Darras Hall, Ridley House, Ridley Avenue, Ponteland, NE20 9JJ Blyth, Northumberland, NE24 3BB, Proposal: Proposed dining room extension; garden room; rooms in roof space with dormer windows Location: 12 Birney Edge, Darras Hall, Ponteland, NE20 9JJ Neighbour Expiry Date: Sept. -

Aspects of the Architectural History of Kirkwall Cathedral Malcolm Thurlby*

Proc Antiqc So Scot, (1997)7 12 , 855-8 Aspects of the architectural history of Kirkwall Cathedral Malcolm Thurlby* ABSTRACT This paper considers intendedthe Romanesque formthe of Kirkwallof eastend Cathedraland presents further evidence failurethe Romanesque for ofthe crossing, investigates exactthe natureof its rebuilding and that of select areas of the adjacent transepts, nave and choir. The extension of the eastern arm is examined with particular attention to the lavish main arcades and the form of the great east window. Their place medievalin architecture Britainin exploredis progressiveand and conservative elements building ofthe evaluatedare context building. the ofthe in use ofthe INTRODUCTION sequence Th f constructioeo t Magnus'S f o n s Cathedra t Kirkwalla l , Orkney comples i , d xan unusual. The basic chronology was established by MacGibbon & Ross (1896, 259-92) and the accoune Orkneth n i ty Inventory e Royath f o l Commissio e Ancienth d Historican o an nt l Monuments of Scotland (RCAHMS 1946,113-25)(illus 1 & 2). The Romanesque cathedral was begun by Earl Rognvald in 1137. Construction moved slowly westwards into the nave before the crossing was rebuilt in the Transitional style and at the same time modifications were made to the transepts includin erectioe gpresene th th f no t square eastern chapels. Shortly after thi sstara t wa sextensioe madth eastere n eo th befor f m no n ar e returnin nave e worgo t th t thi n .A k o s stage no reason was given for the remodelling of the crossing and transepts in the late 12th century. -

Our Economy 2020 with Insights Into How Our Economy Varies Across Geographies OUR ECONOMY 2020 OUR ECONOMY 2020

Our Economy 2020 With insights into how our economy varies across geographies OUR ECONOMY 2020 OUR ECONOMY 2020 2 3 Contents Welcome and overview Welcome from Andrew Hodgson, Chair, North East LEP 04 Overview from Victoria Sutherland, Senior Economist, North East LEP 05 Section 1 Introduction and overall performance of the North East economy 06 Introduction 08 Overall performance of the North East economy 10 Section 2 Update on the Strategic Economic Plan targets 12 Section 3 Strategic Economic Plan programmes of delivery: data and next steps 16 Business growth 18 Innovation 26 Skills, employment, inclusion and progression 32 Transport connectivity 42 Our Economy 2020 Investment and infrastructure 46 Section 4 How our economy varies across geographies 50 Introduction 52 Statistical geographies 52 Where do people in the North East live? 52 Population structure within the North East 54 Characteristics of the North East population 56 Participation in the labour market within the North East 57 Employment within the North East 58 Travel to work patterns within the North East 65 Income within the North East 66 Businesses within the North East 67 International trade by North East-based businesses 68 Economic output within the North East 69 Productivity within the North East 69 OUR ECONOMY 2020 OUR ECONOMY 2020 4 5 Welcome from An overview from Andrew Hodgson, Chair, Victoria Sutherland, Senior Economist, North East Local Enterprise Partnership North East Local Enterprise Partnership I am proud that the North East LEP has a sustained when there is significant debate about levelling I am pleased to be able to share the third annual Our Economy report. -

Northumberland County Council

Northumberland County Council Weekly List of Planning Applications Applications can view the document online at http://publicaccess.northumberland.gov.uk/online-applications If you wish to make any representation concerning an application, you can do so in writing to the above address or alternatively to [email protected]. Any comments should include a contact address. Any observations you do submit will be made available for public inspection when requested in accordance with the Access to Information Act 1985. If you have objected to a householder planning application, in the event of an appeal that proceeds by way of the expedited procedure, any representations that you made about the application will be passed to the Secretary of State as part of the appeal Application No: 19/01367/FUL Expected Decision: Delegated Decision Date Valid: May 7, 2019 Applicant: Mr Philip Mellen-Steele Agent: 9 Queen Street, Alnwick, Northumberland, NE66 1RD, Proposal: Proposed rear ground floor extension to enlarge kitchen, utility and living-room; front elevation bay window at first floor over existing; widen driveway and canopy over garage door Location: 11 Lesbury Road, Lesbury, Northumberland, NE66 3ND Neighbour Expiry Date: May 7, 2019 Expiry Date: July 1, 2019 Case Officer: Mrs Esther Ross Decision Level: Ward: Alnwick Parish: Lesbury Application No: 19/01466/FUL Expected Decision: Delegated Decision Date Valid: May 8, 2019 Applicant: Mrs Rachel Towns Agent: Hilton, New Ridley, Stocksfield, Northumberland, NE43 7RQ, Proposal: Proposed new single storey garage in addition to previously approved scheme. Location: Hilton, New Ridley, Stocksfield, Northumberland, NE43 7RQ, Neighbour Expiry Date: May 8, 2019 Expiry Date: July 2, 2019 Case Officer: Ms Marie Haworth Decision Level: Ward: Stocksfield And Broomhaugh Parish: Stocksfield Application No: 19/00999/FUL Expected Decision: Delegated Decision Date Valid: May 8, 2019 Applicant: Conchie Agent: Half Acres, Catton, Hexham, Northumberland, NE47 9LH, Proposal: 1) Retrospective permission for 14no. -

New Season of Bradford Cathedral Coffee Concerts Begins with Baritone Singer James Gaughan

Date: Thursday 9th January 2020 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE PRESS RELEASE New season of Bradford Cathedral Coffee Concerts begins with baritone singer James Gaughan The monthly Coffee Concerts held at Bradford Cathedral return on Tuesday 14th January when baritone singer James Gaughan performs a programme of music at 11am. Entry is free and refreshments are available from 10:30am. James Gaughan is an experienced soloist specialising in the song and concert repertoire. Based in York, he studies at the De Costa Academy of Singing with Michael De Costa. James gives lunchtime recitals throughout the year. Past performances include at Southwell Minster; Derby, Lincoln, 1 HOSPITALITY. FAITHFULNESS. WHOLENESS. [email protected] Bradford Cathedral, Stott Hill, Bradford, BD1 4EH www.bradfordcathedral.org T: 01274 777720 Sheffield and Wakefield Cathedrals; Emanuel United Reformed Church, Cambridge; Christ Church Harrogate; Hexham Abbey; Great Malvern Priory and others. He also performs regularly as a soloist with choirs and choral societies. Past performances include of Elijah (Mendelssohn); Stabat Mater (Astorga); Cantata 140 (Bach); Ein Deutsches Requiem (Brahms); Requiem (Fauré); Israel in Egypt (Handel); Paukenmesse (Haydn) and Messiah (Handel). James Gaughan: “The programme I’ve prepared is based around the poets, rather than around the composers. I think it’s become quite normal these days to have the historical concerts, where you go from composer to composer and knit them closely together. “What I’ve tried to do with this set-up is to place little sets from different periods of poetry, which means I can have quite a varied set of three songs which could theoretically be from three different centuries which gives a lot of variety for the audience, but still have some coherent link to it.” The monthly Coffee Concert programme continue with saxophonist Rob Burton in February, pianist Jill Crossland in March and Violin and Piano duo James and Alex Woodrow in April. -

Ad122-2016.Pdf

Connections 10 — Newcastle » Metrocentre » Blaydon » Ryton » Prudhoe » Corbridge » Hexham from Newcastle X85 — Newcastle » Benwell Grove » Denton Burn » Heddon-on-the-Wall » Horsley » Corbridge » Hexham Mondays to Fridays (except Public Holidays) Saturdays Sundays (including Public Holidays) Service number 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 Service number 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 Service number 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 Newcastle, Eldon Square 0650 0720 0820 0923 1025 1125 1325 1425 1525 Newcastle, Eldon Square 0700 0730 0830 0925 1025 1125 1325 1425 1525 Newcastle, Eldon Square 0800 0900 0952 1052 1252 1352 1452 Metrocentre 0708 0738 0838 0941 1043 1143 1343 1443 1543 Metrocentre 0716 0746 0846 0943 1043 1143 1343 1443 1543 Metrocentre 0816 0916 1010 1110 1310 1410 1510 Prudhoe Front Street, Co-operative 0737 0808 0909 1013 1115 1215 1415 1516 1617 Prudhoe Front Street, Co-operative 0741 0811 0911 1012 1115 1215 1415 1515 1615 Prudhoe Front Street, Co-operative 0842 0942 1040 1140 1340 1440 1540 Hexham Bus Station 0809 0840 0941 1045 1147 1247 1447 1548 1649 Hexham Bus Station 0810 0840 0940 1044 1147 1247 1447 1547 1647 Hexham Bus Station 0911 1011 1112 1212 1412 1512 1612 Service number X84 X85 X85 X85 X85 X85 X85 X85 X85 Service number X85 X85 X85 X85 X85 X85 X85 Sorry, no service on Sundays or Public Holidays for X84 and X85. Newcastle, Eldon Square 0725 0800 0910 1010 1110 1210 1410 1510 1610 Newcastle, Eldon Square 0910 1010 1110 1210 1410 1510 1610 Hexham Bus Station 0825 0847 0957 1057 1157 1257 1457 1557 1657 Hexham Bus Station 0957 1057 -

For Sale – Residential Development Opportunity

For Sale – Residential Development Opportunity Shaw House Farm, Newton, Stocksfield, Northumberland, NE43 7UE • Residential Development Opportunity • Full Planning Permission Granted • Site Area: 0.5 hectares (1.24 acres) • Planning Reference: 18/03543/FUL Guide Price £950,000 • Rural Location • Freehold ALNWICK | DURHAMD U R H A| M GOSFORTH | N E W C A S | T LMORPETH E | SUNDERLAND | NEWCASTLE | LEEDS | SUNDERLAND D U R H A M | N E W C A S T L E | SUNDERLAND | LEEDS FOR SALE – Residential Development Opportunity Shaw House Farm, Newton, Stocksfield, Northumberland, NE43 7UE OPPORTUNITY Bradley Hall are delighted to offer this residential development opportunity for the conversion of traditional agricultural buildings to 7 residential units with associated access and parking with the demolition of modern agricultural buildings to the north. LOCATION & DESCRIPTION The site is located to the south of Newton, 1.5m to the north of Bywell and 1.9m to the north of Stocksfield which benefits from a train station and bus service links to Hexham. The A69 is located to the south of the farmstead providing access directly into Newcastle to the east and Corbridge/Hexham to the west. The site is located to the east of Shaw House Farmhouse and is bounded by the existing access road leading to Newton on the western boundary. To the southern boundary there is existing residential uses and to the northern and eastern boundaries is open agricultural land. The subject site, known as Shaw House Farm, comprises several agricultural buildings currently utilised for sheep farming. Buildings on site include large, modern steel portal framed barns across the northern portion of the site upon concrete pads; several connected agricultural buildings of sandstone and timber construction, located centrally; and a square shaped barn located to the south-west formed of three rectangular structures, two of sandstone and timber, and the middle of steel portal frame construction. -

MAGAZINE from MEDIEVALISTS.NET the Medieval Magazine Volume 3 Number 4 March 2, 2017

MEDIEVAL STUDIES MAGAZINE FROM MEDIEVALISTS.NET The Medieval Magazine Volume 3 Number 4 March 2, 2017 Miniature of Christine de Pizan breaking up ground while Lady Reason clears away letters to prepare for the building of the City of Ladies. Additional 20698 f. 17 (Netherlands, S. (Bruges) (The British Library). Philippa of Hainault & WomenBook Review of the Medici Travel Tips Anne of Bohemia Eleanor of Toledo The Uffizi The Medieval Magazine March 2, 2017 31 Etheldreda & Ely Cathedral 6 The Queenships of Philippa of Hainault and Anne of Bohemia 28 Book Tour: The Turbulent Crown 37 Travel Tips: Firenze - The Uffizi 57 Queen of the Castle Table of Contents 4 Letter from Editors 6 Intercession and Motherhood: Queenships of Philippa of Hainault and Anne of Bohemia by Conor Byrne 21 Conference News: Medieval Ethiopia at U of Toronto 22 Book Excerpt: Everyday Life in Tudor London by Stephen Porter 28 Book Tour: The Turbulent Crown by Roland Hui 31 Etheldreda: Queen, Abbess, Saint by Jessica Brewer 53 Historic Environment Scotland: Building relationships with metal detectorists 57 Queen of the Castle: Best Medieval Holiday Homes on the Market 63 Book Review: A Medieval Woman's Companion by Susan Signe Morrison 66 Leprosy and Plague at St. Giles in the Fields by Rebecca Rideal Regular Features 20 Talk the Talk - Old Italian, "Fáte Sángue" 27 Building the Medieval - Lady Chapel THE MEDIEVAL MAGAZINE 37 Travel Tips - Florence Editors: Sandra Alvarez and Danielle Trynoski 46 Londinium - Museum of London Website: www.medievalists.net This digital magazine is published bi-monthly. 52 Art/ifact Spotlight - Spindle Whorls & Loom Weights Cover Photo Credit: British Library In Honour of Women “We cannot live in a world that is interpreted for us by others. -

PONTELAND NEIGHBOURHOOD PLAN Health Care and Care of the Elderly Report 1 CONTENTS 1. Introduction and Process 2. Health Servi

PONTELAND NEIGHBOURHOOD PLAN 1 Health Care and Care of the Elderly Report CONTENTS 1. Introduction and Process 2. Health Services Provision 3. Services for Older People 4. Housing Specific for Older People 5. Activities for Older People 6. Infrastructure 7. Key issues identified 8. Our Vision 9. Objectives 10. Proposed Neighbourhood Planning Policies - to be agreed Appendix 1 Questionnaire Appendix 1a - Results from Questionnaire - to follow Appendix 1b - Specific Comments from Questionnaire- to follow Appendix 2 Organisation engagement Appendix 3 Current availability of services Appendix 4 Evidence Appendix 4a – Footpath map Appendix 4b – Bus route map PONTELAND NEIGHBOURHOOD PLAN 2 Health Care and Care of the Elderly Report 1. INTRODUCTION AND PROCESS 1. The purpose of a Neighbourhood Plan for the Parish of Ponteland is to set out a locally developed spatial planning strategy and policies to guide and manage development in Ponteland during the period up to 2031. 2. This report has been prepared by the Health and Older People Sub-Group of the Ponteland Neighbourhood Plan Group. It comprises evidence for the Group in relation to health services provision and the availabilities of services and activities for older people.. The report provides a description of the work undertaken, the information assembled and its assessment. It has been produced to assist in the preparation of a Neighbourhood Plan and its proposals will be reviewed as part of the development of the plan and may be subject to change. 3. Over 35% of the population in Ponteland is over 60, with 13% of these being over 75. A further 23.5% fall into the 45-59 category. -

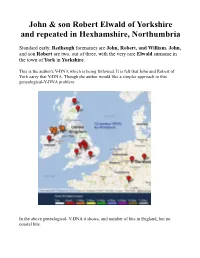

John & Son Robert Elwald of Yorkshire and Repeated in Hexhamshire

John & son Robert Elwald of Yorkshire and repeated in Hexhamshire, Northumbria Standard early, Redheugh forenames are John, Robert, and William. John, and son Robert are two, out of three, with the very rare Elwald surname in the town of York in Yorkshire. This is the author's Y-DNA which is being followed. It is felt that John and Robert of York carry that Y-DNA. Though the author would like a simpler approach to this genealogical-Y-DNA problem. In the above genealogical- Y-DNA it shows, and number of hits in England, but no coastal hits. It should be noted that York is near Wolds (woods), as apposed to the Moors (moorland). Note the location of Scarborough; Hexham north part of map. The first name translated as Johannes (John), and the middle name Johannesen (Johnson (son of John)). So it is in Norway, the name John was held in high, and also surname Walde, for Elwalde is importand. Both German and Danish seem to prefix wald (woods). Elwald surname emerged not as a location such as Scarborough, but as being the son of (fitz) Elwald. It is felt that John and his son Robert could easily carry similar Y- DNA out of the Northumberland, region of York. As one can see above Johannes Elwald mercator quam. This shows, how both Johnannes and Elwald could have strong origins in Denmark German. The name Robert had strong influence after 1320 because of Robert the Bruce, who the Elwald fought for in the separation of the crowns of Scotland and England.