Download/Pnlh-Document-Officiel-002.Pdf>

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dec. 22, 2015 Snd. Tech. Album Arch

SOUND TECHNIQUES RECORDING ARCHIVE (Albums recorded and mixed complete as well as partial mixes and overdubs where noted) Affinity-Affinity S=Trident Studio SOHO, London. (TRACKED AND MIXED: SOUND TECHNIQUES A-RANGE) R=1970 (Vertigo) E=Frank Owen, Robin Geoffrey Cable P=John Anthony SOURCE=Ken Scott, Discogs, Original Album Liner Notes Albion Country Band-Battle of The Field S=Sound Techniques Studio Chelsea, London. (TRACKED AND MIXED: SOUND TECHNIQUES A-RANGE) S=Island Studio, St. Peter’s Square, London (PARTIAL TRACKING) R=1973 (Carthage) E=John Wood P=John Wood SOURCE: Original Album liner notes/Discogs Albion Dance Band-The Prospect Before Us S=Sound Techniques Studio Chelsea, London. (PARTIALLY TRACKED. MIXED: SOUND TECHNIQUES A-RANGE) S=Olympic Studio #1 Studio, Barnes, London (PARTIAL TRACKING) R=Mar.1976 Rel. (Harvest) @ Sound Techniques, Olympic: Tracks 2,5,8,9 and 14 E= Victor Gamm !1 SOUND TECHNIQUES RECORDING ARCHIVE (Albums recorded and mixed complete as well as partial mixes and overdubs where noted) P=Ashley Hutchings and Simon Nicol SOURCE: Original Album liner notes/Discogs Alice Cooper-Muscle of Love S=Sunset Sound Recorders Hollywood, CA. Studio #2. (TRACKED: SOUND TECHNIQUES A-RANGE) S=Record Plant, NYC, A&R Studio NY (OVERDUBS AND MIX) R=1973 (Warner Bros) E=Jack Douglas P=Jack Douglas and Jack Richardson SOURCE: Original Album liner notes, Discogs Alquin-The Mountain Queen S= De Lane Lea Studio Wembley, London (TRACKED AND MIXED: SOUND TECHNIQUES A-RANGE) R= 1973 (Polydor) E= Dick Plant P= Derek Lawrence SOURCE: Original Album Liner Notes, Discogs Al Stewart-Zero She Flies S=Sound Techniques Studio Chelsea, London. -

Turning Bad News Into a Teaching Moment Using the Exploring Humanitarian Law Curriculum to Teach About the Impact of War and Natural Disaster

Social Education 74(5), pp 247–251 ©2010 National Council for the Social Studies Special Section: Exploring Humanitarian Law The Exploring Humanitarian Law program was developed by the International Committee of the Red Cross in 2001 to introduce young people to the basic rules that govern international armed conflict. In the past 10 years, the program has been integrated in the curricula of schools in more than 40 countries in an effort to challenge youth to think about and develop solutions for these modern international issues. The curriculum is divided into five thematic modules— The Humanitarian Perspective, Limits in Armed Conflict, The Law in Action, Ensuring Justice, and Responding to the Consequences of Armed Conflict—and provides educators with more than 30 hours of free material. These EHL resources include lesson plans, primary sources documents, and engaging activities that aim to make the situation of armed conflict more relevant to the everyday experiences of youth, most of whom have never witnessed armed conflict firsthand. Learn more at www.redcross.org/ehl. Turning Bad News into a Teaching Moment Using the Exploring Humanitarian Law curriculum to teach about the impact of war and natural disaster Mat Morgan he head of the American Red Cross has visited Haiti a number of times since 1.7 million people, or nearly 90 percent the devastating earthquake in January that killed more than 200,000 people of the capital city, lived in slums. One Tand left an estimated 1.5 million people homeless. She recalls overwhelming third of residents in Port-au-Prince had feelings of both hope and despair, and it is clear these experiences live on within access to clean water, while no more her. -

00009-2010 ( .Pdf )

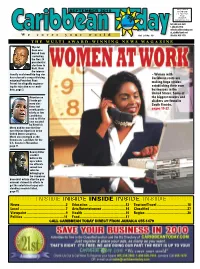

PRESORTED sepTember 2010 STANDARD ® U.S. POSTAGE PAID MIAMI, FL PERMIT NO. 7315 Tel: (305) 238-2868 1-800-605-7516 [email protected] [email protected] We cover your world Vol. 21 No. 10 Jamaica: 655-1479 THE MULTI AWARD-WINNING NEWS MAGAZINE Wyclef Jean was barred from contesting the Nov. 28 presidential elections in Haiti. Now the interna - tionally acclaimed hip-hop star ~ Women with has released a song criticizing Caribbean roots are outgoing President René Préval for allegedly engineer - making huge strides ing his rejection as a candi - establishing their own date, page 2. businesses in the United States. Some of Attention on the biggest movers and Florida pri - shakers are found in mary elec - South Florida, tions last month, partic - pages 19-23 . ularly as four candidates vied to fill the seat vacated by Kendrick Meek and become the first- ever Haitian American in the United States Congress. Meek also emerged as the Democrats’ candidate for the U.S. Senate in November, page 11. Bounty Killer couldn’t believe his eyes when tax officials seized two vehicles belonging to the Jamaican dancehall artiste after the gov - ernment claimed its efforts to get the entertainer to pay out - standing amounts failed, page 15. INSIDE News ......................................................2 Education ............................................12 Tourism/Travel ....................................18 Local ......................................................7 Arts/Entertainment ............................14 Classified ............................................27 -

1 Erin Zavitz and Laurent Dubois, the NEH Collaborative Grant, 2014 1

1 Thomas Madiou, Histoire d’Haïti (Port-au-Prince: Imp de J. Courtois, 1847) Tome 1 Edited and translated by Laurent Dubois and Erin Zavitz Even before insurgent leader Jean-Jacques Dessalines declared Haiti’s independence on January 1, 1804 a plethora of texts were circulating in the Americas and Europe on the revolution in the French colony of Saint Domingue. Over the next decades, Haitian authors took up the challenge of responding to these foreign publications writing their own history of the nation’s founding. One of the seminal works of Haiti’s emerging historiographic tradition is the eight volume Histoire d’Haïti by Thomas Madiou. Published in Port-au-Prince in two installments in 1847 and 1848, the volumes were the first definitive history of Haiti from 1492 to 1846. The translations are from the original publication which I selected because it is now freely available on Google books. Henri Deschamps, a Haitian publishing house, released a more recent reprint between 1988 and 1991 but only limited copies are still available for purchase or held by U.S. libraries. For individuals familiar with the Deschamps edition, the pagination of the 1847/48 Google edition is slightly different. Born in Haiti in 1814 to a mixed race family, Madiou attended school in France from the age of 10. Upon returning to Haiti as an adult, he began publishing articles in Port-au-Prince newspapers only to realize the need for a complete history. Madiou set about reading available print sources and, more importantly, interviewing aging soldiers who fought in the revolution. -

Haitian Historical and Cultural Legacy

Haitian Historical and Cultural Legacy A Journey Through Time A Resource Guide for Teachers HABETAC The Haitian Bilingual/ESL Technical Assistance Center HABETAC The Haitian Bilingual/ESL Technical Assistance Center @ Brooklyn College 2900 Bedford Avenue James Hall, Room 3103J Brooklyn, NY 11210 Copyright © 2005 Teachers and educators, please feel free to make copies as needed to use with your students in class. Please contact HABETAC at 718-951-4668 to obtain copies of this publication. Funded by the New York State Education Department Acknowledgments Haitian Historical and Cultural Legacy: A Journey Through Time is for teachers of grades K through 12. The idea of this book was initiated by the Haitian Bilingual/ESL Technical Assistance Center (HABETAC) at City College under the direction of Myriam C. Augustin, the former director of HABETAC. This is the realization of the following team of committed, knowledgeable, and creative writers, researchers, activity developers, artists, and editors: Marie José Bernard, Resource Specialist, HABETAC at City College, New York, NY Menes Dejoie, School Psychologist, CSD 17, Brooklyn, NY Yves Raymond, Bilingual Coordinator, Erasmus Hall High School for Science and Math, Brooklyn, NY Marie Lily Cerat, Writing Specialist, P.S. 181, CSD 17, Brooklyn, NY Christine Etienne, Bilingual Staff Developer, CSD 17, Brooklyn, NY Amidor Almonord, Bilingual Teacher, P.S. 189, CSD 17, Brooklyn, NY Peter Kondrat, Educational Consultant and Freelance Writer, Brooklyn, NY Alix Ambroise, Jr., Social Studies Teacher, P.S. 138, CSD 17, Brooklyn, NY Professor Jean Y. Plaisir, Assistant Professor, Department of Childhood Education, City College of New York, New York, NY Claudette Laurent, Administrative Assistant, HABETAC at City College, New York, NY Christian Lemoine, Graphic Artist, HLH Panoramic, New York, NY. -

Come to the Races October L<9%0, 26

Come to the Races October l<9%0, 26 * 2 coy** ft iuo »"T0R|gi LAS VEOAS WEATHER BWfOET COURT HOUSE By CHARLES P. SQUIRES ' LAS V£0'A-S ft £ V A 0 A I PLEDGE ALLEGIANCE TO Cooperative Ot—riim THE FLAG OP THE UNITED September tt .... 93 74 STATES OF AMERICA, AMD TO September 99 .... ^..:„82 57 THE REPUBLIC FOR WHICH IT September 29 . 84 55 STANDS, ONE NATION, INDIVIS September 30 86 54 IBLE, WTTH LIBERTY AND JUS October 1 .....w«~ 91 50 TICE FCHl AU.. October. 2 86 56 October 3 80 08 lUTHEPNNfeVADA^ Volume XXXVI, Number 40 LAS.VEOAS, NEVADA, FTVE CENTS PER COPY National Business Women s|f ^SB Bishop Dedicates Race Committee ^^SWeel#)ctober 6 to 12,194tt Beautiful Church To Incorporate"^ Under the leadership of the Most Ibe General Committee rA tba Reverend Thomas K. Gorman, Bish fall race meet inet Tuesday evening THE CHURCH IN LAS VEGAS op of tiie Catholic Church, in Ne at. the municipal court room, witii vada, a group of dignitaries ot tiie The dedication of the new Cath thirty members present including . church performed tiie solemn, digni representatives of nine civic organ olic church Wednesday by Bishop fied and beautiful rites of dedication Gorman and other prelates of tiie izations present and • participating. of the new Church of St. Joan of General Tom .Thebo presided over church who gathered here for that Arc Wednesday morning, in tit* purpose, takes onr minds back to the meeting. He was awtsted by presence of a- congregation which Secretary Tex Blackman . -

Abhyaas News Board … for the Quintessential Test Prep Student

February 5, 2017 ANB20170202 Abhyaas News Board … For the quintessential test prep student 68th Indian Republic Day celebrated The chief guest at the Republic Parade this year The Editor’s Column was Sheikh Mohammed bin Zayed Al Nahyan, the crown prince of Abu Dhabi. Dear Student, A contingent of UAE soldiers marched in the parade. The 149-member Presidential Guard, The new year augurs a lot of new changes. Donald which was led by a UAE band consisting of 35 Trump takes office as the 45th President of USA. The musicians, presented a ceremonial salute to the world watches as he makes sweeping changes in his President and the Chief Guest. A contingent of the first few days in office. National Security Guard (NSG), popularly known as the Black Cat Commandos, also participated in the Padma Awards announced as India celebrated the 68th parade which was commanded by Lt General Republic Day. A departure from the norm, the Budget Manoj Mukund Naravane, General Officer has been presented on Feb 1st. Miss France wins the Commanding, Delhi Area. Miss Universe crown whereas Rogerer Federer wins The army showcased its Tank T-90 and Infantry his 18th Grand Slam title and Serena Williams her 23rd Combat Vehicle and Brahmos Missile, its Weapon title. Locating Radar Swathi, Transportable Satellite Terminal and Akash Weapon System. The Indian Vinod Rai takes over the new BCCI chief and the Air Force tableau had the theme "Air Dominance Chairman of the Tata Group is N Chandra. Through Network Centric Operations". The tableau displayed the scaled down models of Su-30 MKI, Mirage-2000, AWACS, UAV, Apache and Happy Reading !! Communication Satellite. -

Black Sabbath the Complete Guide

Black Sabbath The Complete Guide PDF generated using the open source mwlib toolkit. See http://code.pediapress.com/ for more information. PDF generated at: Mon, 17 May 2010 12:17:46 UTC Contents Articles Overview 1 Black Sabbath 1 The members 23 List of Black Sabbath band members 23 Vinny Appice 29 Don Arden 32 Bev Bevan 37 Mike Bordin 39 Jo Burt 43 Geezer Butler 44 Terry Chimes 47 Gordon Copley 49 Bob Daisley 50 Ronnie James Dio 54 Jeff Fenholt 59 Ian Gillan 62 Ray Gillen 70 Glenn Hughes 72 Tony Iommi 78 Tony Martin 87 Neil Murray 90 Geoff Nicholls 97 Ozzy Osbourne 99 Cozy Powell 111 Bobby Rondinelli 118 Eric Singer 120 Dave Spitz 124 Adam Wakeman 125 Dave Walker 127 Bill Ward 132 Related bands 135 Heaven & Hell 135 Mythology 140 Discography 141 Black Sabbath discography 141 Studio albums 149 Black Sabbath 149 Paranoid 153 Master of Reality 157 Black Sabbath Vol. 4 162 Sabbath Bloody Sabbath 167 Sabotage 171 Technical Ecstasy 175 Never Say Die! 178 Heaven and Hell 181 Mob Rules 186 Born Again 190 Seventh Star 194 The Eternal Idol 197 Headless Cross 200 Tyr 203 Dehumanizer 206 Cross Purposes 210 Forbidden 212 Live Albums 214 Live Evil 214 Cross Purposes Live 218 Reunion 220 Past Lives 223 Live at Hammersmith Odeon 225 Compilations and re-releases 227 We Sold Our Soul for Rock 'n' Roll 227 The Sabbath Stones 230 Symptom of the Universe: The Original Black Sabbath 1970–1978 232 Black Box: The Complete Original Black Sabbath 235 Greatest Hits 1970–1978 237 Black Sabbath: The Dio Years 239 The Rules of Hell 243 Other related albums 245 Live at Last 245 The Sabbath Collection 247 The Ozzy Osbourne Years 249 Nativity in Black 251 Under Wheels of Confusion 254 In These Black Days 256 The Best of Black Sabbath 258 Club Sonderauflage 262 Songs 263 Black Sabbath 263 Changes 265 Children of the Grave 267 Die Young 270 Dirty Women 272 Disturbing the Priest 273 Electric Funeral 274 Evil Woman 275 Fairies Wear Boots 276 Hand of Doom 277 Heaven and Hell 278 Into the Void 280 Iron Man 282 The Mob Rules 284 N. -

Haitian Creole – English Dictionary

+ + Haitian Creole – English Dictionary with Basic English – Haitian Creole Appendix Jean Targète and Raphael G. Urciolo + + + + Haitian Creole – English Dictionary with Basic English – Haitian Creole Appendix Jean Targète and Raphael G. Urciolo dp Dunwoody Press Kensington, Maryland, U.S.A. + + + + Haitian Creole – English Dictionary Copyright ©1993 by Jean Targète and Raphael G. Urciolo All rights reserved. No part of this work may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without the prior written permission of the Authors. All inquiries should be directed to: Dunwoody Press, P.O. Box 400, Kensington, MD, 20895 U.S.A. ISBN: 0-931745-75-6 Library of Congress Catalog Number: 93-71725 Compiled, edited, printed and bound in the United States of America Second Printing + + Introduction A variety of glossaries of Haitian Creole have been published either as appendices to descriptions of Haitian Creole or as booklets. As far as full- fledged Haitian Creole-English dictionaries are concerned, only one has been published and it is now more than ten years old. It is the compilers’ hope that this new dictionary will go a long way toward filling the vacuum existing in modern Creole lexicography. Innovations The following new features have been incorporated in this Haitian Creole- English dictionary. 1. The definite article that usually accompanies a noun is indicated. We urge the user to take note of the definite article singular ( a, la, an or lan ) which is shown for each noun. Lan has one variant: nan. -

AMHE Newsletter Spring 2020 June 8 Haitian Medical Association Abroad Association Medicale Haïtienne À L'étranger Newsletter # 278

AMHE Newsletter spring 2020 june 8 Haitian Medical Association Abroad Association Medicale Haïtienne à l'Étranger Newsletter # 278 AMHE NEWSLETTER Editor in Chief: Maxime J-M Coles, MD Editorial Board: Rony Jean Mary, MD Reynald Altema, MD Technical Adviser: Jacques Arpin Antoine Louis Leocardie Elie Lescot Maxime Coles MD Antoine Louis Leocardie Lescot become president of the republique of Haiti on May 15, 1941. Issued from a privileged society, he used his political influence during the second war to claim the higher position of the land. He ascended to the presidency in gaining power through his ties with the United States of America. He was a mulattoe, issued from the elites and the post war climate allowed his administration to reign over a period of political downturn after many political repression of the dissidents. Elie Lescot was born at Saint Louis du Nord (Nord West of Haiti) on December 9, 1883 in a middleclass family. His father, Ovide Lescot is a resident in Cap-Haiti and decided to protect his pregnant wife, Florelia Laforest, from his political opponents. He chose to relocate her to St Louis du Nord under the protection of her sister Lea, wife of a Guadeloupean business holder and sometimes architect, Edouard Elizee. Ovide Lescot was the son of Pierre Joseph Lescot with Marie-Michelle Morin but he later re- married to Marie-Fortunée Deneau who gave him two daughters: Therese and Leticia. Therese became the wife of the well-known poet Oswald Durand while Laeticia will marry Chery Hippolyte, son of President Florville Hippolyte. Florelia Laforest had an extramarital affair with president Sylvain Salnave before knowing Ovide Lescot In this number - Words of the Editor, Maxime Coles,MD - Article de Axler JEAN PAUL - La chronique de Rony Jean-Mary,M.D. -

Towards a Holistic Interpretation of Musical Genre Analysis Thesis

1 JYVÄSKYLÄ STUDIES IN HUMANITIES Chris Kemp Towards a Holistic Interpretation of Musical Genre Analysis JYVÄSKYLÄN YLIOPISTO 1 2 JYVÄSKYLÄ STUDIES IN HUMANITIES Chris Kemp Towards a Holistic Interpretation of Musical Genre Analysis Academic dissertation to be publicly discussed, by permission of the Faculty of Humanities at the University of Jyväskylä, in Auditorium S212, on June 10, 2004 at 12 o’clock noon. 2 3 Towards a Holistic Interpretation of Musical Genre Analysis JYVÄSKYLÄ STUDIES IN HUMANITIES 3 4 Chris Kemp Towards a Holistic Interpretation of Musical Genre Analysis Academic dissertation to be publicly discussed, by permission of the Faculty of Humanities at the University of Jyväskylä, in Auditorium S212, on June 10, 2004 at 12 o’clock noon. 4 5 ABSTRACT Kemp, Chris Towards a holistic interpretation of musical genre analysis Jyväskylä: University of Jyväskylä, 2004 ? (Jyväskylä Studies in Humanities ISSN ISBN Diss In the past, exploration of music has focused on analysis by formalists, refferentialists and through social, semiotic and anthropological viewpoints including Schenkerian-Yeston (1977), Semiotic-Eco (1977), and Motivic-Ruwet (1987). Although each has its merits in the formal analysis of music, few explore genre identification. In musical genre studies the exploration of musical, paramusical (extramusical) and perceptual elements are essential to facilitate a full understanding of the subject area. Johnson in Zorn supports such a perspective in his argument for a holistic approach to musical analysis (Zorn 2000:29). The multidisciplinary nature of music and the discourses embodied in its creation, development and dissemination utilise a range of signifiers for identification advocating the utilisation of a “hybrid” (Wickens 1999) methodology combining quantitative and qualitative analysis. -

PORT-AU-PRINCE and MONTREAL, 1934-1986 by Grace Louise Sanders a Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requiremen

LA VOIX DES FEMMES: HAITIAN WOMEN’S RIGHTS, NATIONAL POLITICS AND BLACK ACTIVISM IN PORT-AU-PRINCE AND MONTREAL, 1934-1986 by Grace Louise Sanders A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (History and Women’s Studies) in the University of Michigan 2013 Dissertation Committee: Associate Professor Sueann Caulfield, Chair Associate Professor Jesse E. Hoffnung-Garskof Professor Tiya A. Miles Associate Professor Nadine C. Naber Professor Matthew J. Smith, University of the West Indies © Grace L. Sanders 2013 DEDICATION For LaRosa, Margaret, and Johnnie, the two librarians and the eternal student, who insisted that I honor the freedom to read and write. & For the women of Le Cercle. Nou se famn tout bon! ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank the History and Women’s Studies Departments at the University of Michigan. I am especially grateful to my Dissertation Committee Members. Matthew J. Smith, thank you for your close reading of everything I send to you, from emails to dissertation chapters. You have continued to be selfless in your attention to detail and in your mentorship. Jesse Hoffnung-Garskof, thank you for sharing new and compelling ways to narrate and teach the histories of Latin America and North America. Tiya Miles, thank you for being a compassionate mentor and inspiring visionary. I have learned volumes from your example. Nadine Naber, thank you for kindly taking me by the hand during the most difficult times on this journey. You are an ally and a friend. Sueann Caulfield, you have patiently walked this graduate school road with me from beginning to end.