UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE Interiority and Counter

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

I Wanna Be Me”

Introduction The Sex Pistols’ “I Wanna Be Me” It gave us an identity. —Tom Petty on Beatlemania Wherever the relevance of speech is at stake, matters become political by definition, for speech is what makes man a political being. —Hannah Arendt, The Human Condition here fortune tellers sometimes read tea leaves as omens of things to come, there are now professionals who scrutinize songs, films, advertisements, and other artifacts of popular culture for what they reveal about the politics and the feel W of daily life at the time of their production. Instead of being consumed, they are historical artifacts to be studied and “read.” Or at least that is a common approach within cultural studies. But dated pop artifacts have another, living function. Throughout much of 1973 and early 1974, several working- class teens from west London’s Shepherd’s Bush district struggled to become a rock band. Like tens of thousands of such groups over the years, they learned to play together by copying older songs that they all liked. For guitarist Steve Jones and drummer Paul Cook, that meant the short, sharp rock songs of London bands like the Small Faces, the Kinks, and the Who. Most of the songs had been hits seven to ten 1 2 Introduction years earlier. They also learned some more current material, much of it associated with the band that succeeded the Small Faces, the brash “lad’s” rock of Rod Stewart’s version of the Faces. Ironically, the Rod Stewart songs they struggled to learn weren’t Rod Stewart songs at all. -

Here Is a Printable

Ryan Leach is a skateboarder who grew up in Los Angeles and Ventura County. Like Belinda Carlisle and Lorna Doom, he graduated from Newbury Park High School. With Mor Fleisher-Leach he runs Spacecase Records. Leach’s interviews are available at Bored Out (http://boredout305.tumblr.com/). Razorcake is a bi-monthly, Los Angeles-based fanzine that provides consistent coverage of do-it-yourself punk culture. We believe in positive, progressive, community-friendly DIY punk, and are the only bona fide 501(c)(3) non-profit music magazine in America. We do our part. An Oral History of The Gun Club originally appeared in Razorcake #29, released in December 2005/January 2006. Original artwork and layout by Todd Taylor. Photos by Edward Colver, Gary Leonard and Romi Mori. Cover photo by Edward Colver. Zine design by Marcos Siref. Printing courtesy of Razorcake Press, Razorcake.org he Gun Club is one of Los Angeles’s greatest bands. Lead singer, guitarist, and figurehead Jeffrey Lee Pierce fits in easily with Tthe genius songwriting of Arthur Lee (Love), Chris Hillman (Byrds), and John Doe and Exene (X). Unfortunately, neither he nor his band achieved the notoriety of his fellow luminary Angelinos. From 1979 to 1996, Jeffrey manned the Gun Club ship through thick and mostly thin. Understandably, the initial Fire of Love and Miami lineup of Ward Dotson (guitar), Rob Ritter (bass), Jeffrey Lee Pierce (vocals/ guitar) and Terry Graham (drums) remains the most beloved; setting the spooky, blues-punk template for future Gun Club releases. At the time of its release, Fire of Love was heralded by East Coast critics as one of the best albums of 1981. -

Read Razorcake Issue #27 As A

t’s never been easy. On average, I put sixty to seventy hours a Yesterday, some of us had helped our friend Chris move, and before we week into Razorcake. Basically, our crew does something that’s moved his stereo, we played the Rhythm Chicken’s new 7”. In the paus- IInot supposed to happen. Our budget is tiny. We operate out of a es between furious Chicken overtures, a guy yelled, “Hooray!” We had small apartment with half of the front room and a bedroom converted adopted our battle call. into a full-time office. We all work our asses off. In the past ten years, That evening, a couple bottles of whiskey later, after great sets by I’ve learned how to fix computers, how to set up networks, how to trou- Giant Haystacks and the Abi Yoyos, after one of our crew projectile bleshoot software. Not because I want to, but because we don’t have the vomited with deft precision and another crewmember suffered a poten- money to hire anybody to do it for us. The stinky underbelly of DIY is tially broken collarbone, This Is My Fist! took to the six-inch stage at finding out that you’ve got to master mundane and difficult things when The Poison Apple in L.A. We yelled and danced so much that stiff peo- you least want to. ple with sourpusses on their faces slunk to the back. We incited under- Co-founder Sean Carswell and I went on a weeklong tour with our aged hipster dancing. -

SUBCULTURE: the MEANING of STYLE with Laughter in the Record-Office of the Station, and the Police ‘Smelling of Garlic, Sweat and Oil, But

DICK HEBDIGE SUBCULTURE THE MEANING OF STYLE LONDON AND NEW YORK INTRODUCTION: SUBCULTURE AND STYLE I managed to get about twenty photographs, and with bits of chewed bread I pasted them on the back of the cardboard sheet of regulations that hangs on the wall. Some are pinned up with bits of brass wire which the foreman brings me and on which I have to string coloured glass beads. Using the same beads with which the prisoners next door make funeral wreaths, I have made star-shaped frames for the most purely criminal. In the evening, as you open your window to the street, I turn the back of the regulation sheet towards me. Smiles and sneers, alike inexorable, enter me by all the holes I offer. They watch over my little routines. (Genet, 1966a) N the opening pages of The Thief’s Journal, Jean Genet describes how a tube of vaseline, found in his Ipossession, is confiscated by the Spanish police during a raid. This ‘dirty, wretched object’, proclaiming his homosexuality to the world, becomes for Genet a kind of guarantee - ‘the sign of a secret grace which was soon to save me from contempt’. The discovery of the vaseline is greeted 2 SUBCULTURE: THE MEANING OF STYLE with laughter in the record-office of the station, and the police ‘smelling of garlic, sweat and oil, but . strong in their moral assurance’ subject Genet to a tirade of hostile innuendo. The author joins in the laughter too (‘though painfully’) but later, in his cell, ‘the image of the tube of vaseline never left me’. -

© Sex Pistols Sessions Spreadsheet © 2013 God Save the Sex Pistols Studio Sessions Spreadsheet

©www.sex-pistols.net Sex Pistols Sessions Spreadsheet ©www.sex-pistols.net 2013 God Save The Sex Pistols Studio Sessions Spreadsheet. Exclusive ©www.sex-pistols.net 2013 Date Version Super Deluxe SEXBOX1 This Is Crap No Future Spunk Swindle v3 Other CDs Track Time * Track Time * Track Time * Track Time * Track Time * Track Time * Track Time Detail * Chris Spedding Session – Majestic Studios, May 1976 Problems 15/05/1977 1–18 03:41 13 03:36 No Feelings 15/05/1977 1–20 02:42 14 02:42 Pretty Vacant 15/05/1977 1–19 02:44 15 02:45 Dave Goodman Session 1 – Denmark Street & Riverside Studios, July 1976 Pretty Vacant 13–30/07/76 2–01 03:53 1 1 03:29 14 03:30 Lazy Sod 13–30/07/76 1 02:08 2 02:07 1 02:09 Satellite 13–30/07/76 2 04:10 3 04:10 2 04:12 No Feeling 13–30/07/76 Single 2B 2–01 02:46 1–14 02:47 3 02:51 4 02:51 3 02:54 I Wanna Be Me 13–30/07/76 Single 1B –––– –––– 1–13 03:06 4 03:10 5 03:11 4 03:16 3 03:03 Anarchy CD Submission 13–30/07/76 2–02 04:08 5 04:17 6 04:16 5 04:17 Anarchy In The UK 13–30/07/76 21 03:58 7 03:59 13 03:59 Dave Goodman Session 2 – Lansdowne & Wessex Studios, October 1976 Anarchy In The UK 10–12/10/76 6 04:07 8 04:09 6 04:10 Anarchy In The UK 10–12/10/76 Mike Thorne Remix 2–03 04:05 2 04:04 Anarchy CD Substitute 10–12/10/76 2–04 03:10 10 03:06 2 No Lip 10–12/10/76 2–05 03:15 11 03:27 2 Stepping Stone 10–12/10/76 2–06 03:00 12 03:05 2 Johnny B Goode 10–12/10/76 2–07 01:44 3 02:34 2 Road Runner 10–12/10/76 2–08 04:10 4 03:39 2 Watcha Gonna Do About It 10–12/10/76 2–09 01:57 7 01:53 2 4 01:53 Vacant CD2 2 No Fun 10–12/10/76 -

King Mob Echo: from Gordon Riots to Situationists & Sex Pistols

KING MOB ECHO FROM 1780 GORDON RIOTS TO SITUATIONISTS SEX PISTOLS AND BEYOND BY TOM VAGUE INCOMPLETE WORKS OF KING MOB WITH ILLUSTRATIONS IN TWO VOLUMES DARK STAR LONDON ·- - � --- Printed by Polestar AUP Aberdeen Limited, Rareness Rd., Altens Industrial Estate, Aberdeen AB12 3LE § 11JJJDJJDILIEJMIIENf1r 1f(Q) KIINCGr JMI(Q)IB3 JECCIHI(Q) ENGLISH SECTION OF THE SITUATIONIST INTERNATIONAL IF([J)IF ffiIE V ([J) IL lUilII ([J) W §IFIEIEIIJ) IHIII§il([J) ffiY ADDITIONAL RESEARCH BY DEREK HARRIS AND MALCOLM HOPKINS Illustrations: 'The Riots in Moorfields' (cover), 'The London Riots', 'at Langdale's' by 'Phiz' Hablot K. Browne, Horwood's 1792-9 'Plan of London', 'The Great Rock'n'Roll Swindle', 'Oliver Twist Manifesto' by Malcolm McLaren. Vagrants and historical shout outs: Sandra Belgrave, Stewart Home, Mark Jackson, Mark Saunders, Joe D. Stevens at NDTC, Boz & Phiz, J. Paul de Castro, Blue Bredren, Cockney Visionaries, Dempsey, Boss Goodman, Lord George Gordon, Chris Gray, Jonathon Green, Jefferson Hack, Christopher Hibbert, Hoppy, Ian Gilmour, Ish, Dzifa & Simone at The Grape, Barry Jennings, Joe Jones, Shaun Kerr, Layla, Lucas, Malcolm McLaren, John Mead, Simon Morrissey, Don Nicholson-Smith, Michel Prigent (pre-publicity), Charlie Radcliffe, Jamie Reid, George Robertson & Melinda Mash, Dragan Rad, George Rude, Naveen Saleh, Jon Savage, Valerie Solanas, Carolyn Starren & co at Kensington Library, Mark Stewart, Toko, Alex Trocchi, Fred & Judy Vermorel, Warren, Dr. Watson, Viv Westwood, Jack Wilkes, Dave & Stuart Wise Soundtrack: 'It's a London Thing' Scott Garcia, 'Going Mobile' The Who, 'Living for the City' Stevie Wonder, 'Boston Tea Party' Alex Harvey, 'Catholic Day' Adam and the Ants, 'Do the Strand' Roxy Music', 'Rev. -

CHRISTIAN DEATH Street Date: Only Theatre of Pain, LP AVAILABLE NOW!

CHRISTIAN DEATH Street Date: Only Theatre of Pain, LP AVAILABLE NOW! INFORMATION: Artist Hometown: Los Angeles Key Markets: Los Angeles, Orange County CA, New York, Europe (France, Germany, Belgium in particular), Japan, Mexico For Fans of: ROZZ WILLIAMS, 45 GRAVE, BAUHAUS, XMAL DEUTSCHLAND, SIOUXSIE AND THE BANSHEES, DELERIUM, SWANS The founding fathers of American goth-rock, CHRISTIAN DEATH released their debut, Only Theatre of Pain, on Frontier Records in March 1982, and that landmark album has had an enormous influence on goth, death-rock, ARTIST: CHRISTIAN DEATH dark-wave, metal and even industrial music scenes all over the world, TITLE: Only Theatre of Pain shaping the approach of more bands than can be counted. Led by vocalist LABEL: Frontier Records and founder Rozz Williams, the CHRISTIAN DEATH of Only Theatre of Pain CAT#: 31007-1-W included guitarist Rikk Agnew, fresh out of THE ADOLESCENTS, bassist FORMAT: LP James McGearty, drummer George Belanger and backing vocals from GENRE: Gothic Rock, Goth, Superheroines leader (and Rozz’s future wife), Eva O as well as performance Death Rock, Punk artist Ron Athey. It was this line-up, with its dirgy, effects-laden guitar riffs BOX LOT: 50 and ambient horror-soundtrack synths, that crystalized the ominous post- SRLP: $14.98 punk sound that has established this album as the ultimate archetype of goth UPC: 018663100715 EXPORT: NO RESTRICTIONS sensibility. Genre touchstones include “Romeo’s Distress,” “Spiritual Cramp” and “Mysterium Iniquitatis.” Marketing Points: Tracklist: • This is a one-time only MISS-PRESS of the newly remastered version of 1. Cavity - First Communion the OTOP but with the previous edition’s black and gold LP jacket 2. -

Razorcake Issue #25 As A

ot too long ago, I went to visit some relatives back in Radon, the Bassholes, or Teengenerate, during every spare moment of Alabama. At first, everybody just asked me how I was my time, even at 3 A.M., was often the only thing that made me feel N doing, how I liked it out in California, why I’m not mar- like I could make something positive out of my life and not just spend N it mopping floors. ried yet, that sort of thing. You know, just the usual small talk ques- tions that people feel compelled to ask, not because they’re really For a long time, records, particularly punk rock records, were my interested but because they’ll feel rude if they don’t. Later on in the only tether to any semblance of hope. Growing up, I was always out of day, my aunt started talking to me about Razorcake, and at one point place even among people who were sort of into the same things as me. she asked me if I got benefits. It’s probably a pretty lame thing to say, but sitting in my room listen- I figured that it was pretty safe to assume that she didn’t mean free ing to Dillinger Four or Panthro UK United 13 was probably the only records and the occasional pizza. “You mean like health insurance?” time that I ever felt like I wasn’t alone. “Yeah,” she said. “Paid vacation, sick days, all that stuff. But listening to music is kind of an abstract. -

The Life and Politics of David Widgery David Renton

The Life and Politics of David Widgery David Renton David Widgery (1947-1992) was a unique figure on the British left. Better than any one else, his life expressed the radical diversity of the 1968 revolts. While many socialists could claim to have played a more decisive part in any one area of struggle - trade union, gender or sexual politics, radical journalism or anti- racism - none shared his breadth of activism. Widgery had a remarkable abili- ty to "be there," contributing to the early debates of the student, gay and femi- nist movements, writing for the first new counter-cultural, socialist and rank- and-file publications. The peaks of his activity correspond to the peaks of the movement. Just eighteen years old, Widgery was a leading part of the group that established Britain's best-known counter-cultural magazine Oz. Ten years later, he helped to found Rock Against Racism, parent to the Anti-Nazi League, and responsible for some of the largest events the left has organised in Britain. RAR was the left's last great flourish, before Margaret Thatcher became Prime Minister, and the movement entered a long period of decline, from which even now it is only beginning to awake. David Widgery was a political writer. Some of the breadth of his work can be seen in the range of the papers for which he wrote. His own anthology of his work, compiled in 1989 includes articles published in City Limits, Gay Left, INK, International Socialism, London Review of Books, Nation Review, New Internationalist, New Socialist, New Society, New Statesman, Oz, Radical America, Rank and File Teacher,Socialist Worker, Socialist Review, Street Life, Temporary Hoarding, Time Out and The Wire.' Any more complete list would also have to include his student journalism and regular columns in the British Medical Journal and the Guardian in the 1980s. -

The RETURN LIVING DEAD the RETURN LIVING DEAD

The RETURN SELLING POINTS: OF THE • Co-written by John Russo, who was George Romero’s writing partner, 1985’s The Return of the Living Dead Was the Punk Rock Sequel to Night LIVING DEAD of the Living Dead • Was the First Film to Feature Brain-Eating Zombies Original Soundtrack SONGS: (Limited Black & Red Starbust Vinyl Edition) • The Amazing Soundtrack Included SIDE ONE Songs by The Cramps, 45 Grave, 1. Surfin’ Dead The Cramps The Damned, T.S.O.L., The Flesh STREET DATE: October 14, 2016 Eaters, The Jet Black Berries, and 2. Partytime More Notorious Punk and Death (Zombie Version) 45 Grave Rock Acts 3. Nothing for You T.S.O.L. There are zombies…and • Original Cover and Label Art 4. Eyes Without a Face then there are brain-eating The Flesh Eaters • Limited Edition of 600 Copies in zombies! And Return of the Living Dead was the 5. Burn the Flames Black and Red Starburst Vinyl Roky Erickson film where brain-eating zombies got their first lease on, er, life. Co-written by John Russo, who was George Romero’s writing partner on Night of SIDE TWO the Living Dead, this 1985 quasi-sequel 1. Dead Beat Dance introduced more “splatstick” humor to the horror The Damned formula as well as the indelible image of ghouls 2. Take a Walk Tall Boys groaning “Braainsss” as they shuffle along. All set 3. Love Under Will The Jet Black Berries to a KILLER score featuring the greatest punk 4. Tonight (We’ll Make Love and death rock bands of the era, including The Until We Die) SSQ 8848064 00501 Cramps, 45 Grave, The Flesh Eaters, The 5. -

Order Form Full

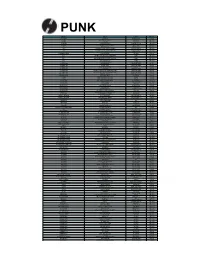

PUNK ARTIST TITLE LABEL RETAIL 100 DEMONS 100 DEMONS DEATHWISH INC RM90.00 4-SKINS A FISTFUL OF 4-SKINS RADIATION RM125.00 4-SKINS LOW LIFE RADIATION RM114.00 400 BLOWS SICKNESS & HEALTH ORIGINAL RECORD RM117.00 45 GRAVE SLEEP IN SAFETY (GREEN VINYL) REAL GONE RM142.00 999 DEATH IN SOHO PH RECORDS RM125.00 999 THE BIGGEST PRIZE IN SPORT (200 GR) DRASTIC PLASTIC RM121.00 999 THE BIGGEST PRIZE IN SPORT (GREEN) DRASTIC PLASTIC RM121.00 999 YOU US IT! COMBAT ROCK RM120.00 A WILHELM SCREAM PARTYCRASHER NO IDEA RM96.00 A.F.I. ANSWER THAT AND STAY FASHIONABLE NITRO RM119.00 A.F.I. BLACK SAILS IN THE SUNSET NITRO RM119.00 A.F.I. SHUT YOUR MOUTH AND OPEN YOUR EYES NITRO RM119.00 A.F.I. VERY PROUD OF YA NITRO RM119.00 ABEST ASYLUM (WHITE VINYL) THIS CHARMING MAN RM98.00 ACCUSED, THE ARCHIVE TAPES UNREST RECORDS RM108.00 ACCUSED, THE BAKED TAPES UNREST RECORDS RM98.00 ACCUSED, THE NASTY CUTS (1991-1993) UNREST RM98.00 ACCUSED, THE OH MARTHA! UNREST RECORDS RM93.00 ACCUSED, THE RETURN OF MARTHA SPLATTERHEAD (EARA UNREST RECORDS RM98.00 ACCUSED, THE RETURN OF MARTHA SPLATTERHEAD (SUBC UNREST RECORDS RM98.00 ACHTUNGS, THE WELCOME TO HELL GOING UNDEGROUND RM96.00 ACID BABY JESUS ACID BABY JESUS SLOVENLY RM94.00 ACIDEZ BEER DRINKERS SURVIVORS UNREST RM98.00 ACIDEZ DON'T ASK FOR PERMISSION UNREST RM98.00 ADICTS, THE AND IT WAS SO! (WHITE VINYL) NUCLEAR BLAST RM127.00 ADICTS, THE TWENTY SEVEN DAILY RECORDS RM120.00 ADOLESCENTS ADOLESCENTS FRONTIER RM97.00 ADOLESCENTS BRATS IN BATTALIONS NICKEL & DIME RM96.00 ADOLESCENTS LA VENDETTA FRONTIER RM95.00 ADOLESCENTS -

Professor and the Madman Are Set to Expand Beyond the Confines of Their Punk Rock Legacies with the Kaleidoscopic Sounds of Disintegrate Me

REMEMBER WHEN ROCK ‘N’ ROLL WAS EXCITING? PROFESSOR AND THE MADMAN ARE SET TO EXPAND BEYOND THE CONFINES OF THEIR PUNK ROCK LEGACIES WITH THE KALEIDOSCOPIC SOUNDS OF DISINTEGRATE ME THE FIRST IMPORTANT NEW ROCK BAND OF 2018 COMPRISES ALFIE AGNEW (Adolescents, D.I.), SEAN ELLIOTT (D.I., Mind Over Four), PAUL GRAY (The DaMned, Eddie & the Hot Rods, UFO) AND RAT SCABIES (The DaMned) Disintegrate Me released on clear vinyl, CD & download by Fullertone Records on February 23, 2018 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE / January 22, 2018 - Southern California’s PROFESSOR AND THE MADMAN are reaDy for the curtain to rise on the group’s worlD Debut. InspireD by Universal horror Movies, the literature of EDgar Allan Poe, anD the chaos of the world arounD theM, the four veteran Musicians who coMprise PROFESSOR AND THE MADMAN are co-frontMen/songwriters Alfie Agnew anD Sean Elliott, alongsiDe the legenDary rhythM section of DruMMer Rat Scabies anD bassist Paul Gray. The group’s new albuM, Disintegrate Me, is releaseD on clear vinyl, CD & DownloaD by FullerTone Records on February 23, 2018. It Marks Gray’s Debut in the group. Co-produced by the band and David M. Allen (The Cure, The DaMneD, The Sisters of Mercy), Disintegrate Me’s nine tracks encoMpass elements of British Invasion rock, Britpop, psych, Prog, power pop, anD even country, all unDerpinneD by the MeloDic punk energy so clearly iMprinteD on the banD’s DNA. Agnew anD Elliott wrote all of the songs anD take turns singing leaD. There’s a deep sense of introspection at the heart of Disintegrate Me as songs grapple with lack of Direction in life, DreaMs unfulfilled, and coMing to terMs with the loss of frienDs anD faMily.