Lyceum of Martial and Societal Antediluvian Chronicles

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

"Fifth" Maryland at Guilford Courthouse: an Exercise in Historical Accuracy - L

HOME CMTE. SUBMISSIONS THE "FIFTH" MARYLAND AT GUILFORD COURTHOUSE: AN EXERCISE IN HISTORICAL ACCURACY - L. E. Babits, February 1988 Over the years, an error has gradually crept into the history of the Maryland Line. The error involves a case of mistaken regimental identity in which the Fifth Maryland is credited with participation in the battle of Guilford Courthouse at the expense of the Second Maryland.[1] When this error appeared in the Maryland Historical Magazine,[2] it seemed time to set the record straight. The various errors seem to originate with Mark Boatner. In his Encyclopedia of the American Revolution, Boatner, while describing the fight at Guilford Courthouse, states: As the 2/Gds prepared to attack without waiting for the three other regiments to arrive, Otho Williams, "charmed with the late demeanor of the first regiment (I Md), hastened toward the second (5th Md) expecting a similar display...". But the 5th Maryland was virtually a new regiment. "The sight of the scarlet and steel was too much for their nerves," says Ward.[3] In this paragraph Boatner demonstrates an ignorance of the actual command and organizational structure of Greene's Southern Army because he quotes from Ward's l94l work on the Delaware Line and Henry Lee's recollections of the war, both of which correctly identify the unit in question as the Second Maryland Regiment.[4] The writer of the Kerrenhappuch Turner article simply referred to Boatner's general reference on the Revolutionary War for the regimental designation.[5] Other writers have done -

The Linden Times

The Linden Times A bi-weekly newsletter for the members & friends of the Calvert County Historical Society – March 19, 2021 This edition of The Linden Times is four pages in celebration of The Maryland 400. No, the Maryland 400 is not a NASCAR race held in Maryland; rather it is about Maryland’s first and most distinguished Revolutionary soldiers. The Maryland 400, also called “The Old Line” , were members of the 1st Maryland Regiment who repeatedly charged a numerically superior British force during the The Maryland 400 at the Battle of Brooklyn Revolutionary War’s Battle of Long Island, NY. As the leading conflict after the signing of the Declaration of Independence, the fallen soldiers were the first to die as Americans defending their country, as opposed to colonial subjects rebelling against the monarchy. The Maryland 400 sustained very heavy casualties but allowed General Washington to successfully save the bulk of his nearly surrounded continental troops and evacuated them to Manhattan. This historic action is commemorated in the State of Maryland's nickname, “The Old Line State." The lineage for the Maryland Regiment can be traced to June 14, 1775, when military units were formed to protect the frontiers of western Maryland. In August of that year, another two companies assembled in Frederick, Maryland. They then marched 551 miles in 21 days to support General Washington’s efforts to drive the British out of Boston. Later, more Maryland militia companies, (armed with older, surplus British muskets and bayonets), were formed and then sent north to support Washington’s battles for New York City. -

Delaware in the American Revolution (2002)

Delaware in the American Revolution An Exhibition from the Library and Museum Collections of The Society of the Cincinnati Delaware in the American Revolution An Exhibition from the Library and Museum Collections of The Society of the Cincinnati Anderson House Washington, D. C. October 12, 2002 - May 3, 2003 HIS catalogue has been produced in conjunction with the exhibition, Delaware in the American Revolution , on display from October 12, 2002, to May 3, 2003, at Anderson House, THeadquarters, Library and Museum of the Society of the Cincinnati, 2118 Massachusetts Avenue, NW, Washington, D. C. 20008. It is the sixth in a series of exhibitions focusing on the contributions to the American Revolution made by the original 13 he season loudly calls for the greatest efforts of every states and the French alliance. Tfriend to his Country. Generous support for this exhibition was provided by the — George Washington, Wilmington, to Caesar Rodney, Delaware State Society of the Cincinnati. August 31, 1777, calling for the assistance of the Delaware militia in rebuffing the British advance to Philadelphia. Collections of the Historical Society of Delaware Also available: Massachusetts in the American Revolution: “Let It Begin Here” (1997) New York in the American Revolution (1998) New Jersey in the American Revolution (1999) Rhode Island in the American Revolution (2000) Connecticut in the American Revolution (2001) Text by Ellen McCallister Clark and Emily L. Schulz. Front cover: Domenick D’Andrea. “The Delaware Regiment at the Battle of Long Island, August 27, 1776.” [detail] Courtesy of the National Guard Bureau. See page 11. ©2002 by The Society of the Cincinnati. -

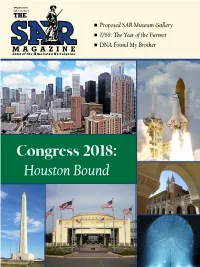

Link.Net Chancellor General Davis Lee Wright, Esq., P.O

SPRING 2018 Vol. 112, No. 4 n Proposed SAR Museum Gallery n 1768: The Year of the Farmer n DNA Found My Brother Congress 2018: Houston Bound SPRING 2018 Vol. 112, No. 4 6 16 6 2018 Congress to Convene 10 America’s Heritage and the 22 Newly Acquired Letters in Houston SAR Library Reveal More About the Maryland 400 7 Amendment Proposal/ 11 The Proposed SAR Museum Leadership Medical Committee Gallery 24 State Society & Chapter News 8 Nominating Committee Report/Butler Awarded 16 250th Series: 1768—The Year 38 In Our Memory/ Medal of Honor of the Farmer New Members 9 Newsletter Competitions 20 DNA Found My Brother 47 When You Are Traveling THE SAR MAGAZINE (ISSN 0161-0511) is published quarterly (February, May, August, November) and copyrighted by the National Society of the Sons of the American Revolution, 809 West Main Street, Louisville, KY 40202. Periodicals postage paid at Louisville, KY and additional mailing offices. Membership dues include The SAR Magazine. Subscription rate $10 for four consecutive issues. Single copies $3 with checks payable to “Treasurer General, NSSAR” mailed to the HQ in Louisville. Products and services advertised do not carry NSSAR endorsement. The National Society reserves the right to reject content of any copy. Send all news matter to Editor; send the following to NSSAR Headquarters: address changes, election of officers, new members, member deaths. Postmaster: Send address changes to The SAR Magazine, 809 West Main Street, Louisville, KY 40202. PUBLISHER: STAFF DIRECTORY President General Larry T. Guzy As indicated below, staff members have an email address and an extension number of the automated 4531 Paper Mill Road, SE telephone system to simplify reaching them. -

Brooklyn, New York

HOLY NAME OF JESUS CHURCH WINDSOR TERRACE BROOKLYN, NEW YORK Fr. Lawrence D. Ryan, Pastor Mrs. Ann Dolan, Parish Trustee Deacon Abel Torres Mr. Philip Lehpamer, Parish Trustee Deacon Michael Saez Mrs. Kathryn Sisto, Religious Education Coordinator Rev. Austin Emeh, In Residence Ms. Ivonne Rojas, Director of Music Rev. Patrick Burns, In Residence St. Joseph the Worker Catholic Academy REV. Msgr. Michael J. Curran, Weekend Assistant Ms. Kathleen Schneck, Principal Mrs. Louise O’Connor, Office Manager Ms. Jennifer Gallina, Assistant Principal Mrs. Louise Witthohn, Academy Secretary Website: www.holynamebrooklyn.com We are also on Facebook and Twitter SUNDAY EUCHARIST - MISA DOMINICALES THE SACRAMENT OF RECONCILIATION - PENITENCIA Saturday: 5:30pm. Saturday: 4:00 to 5:00 pm. Sunday: 7:30, 9:00 (Spanish), 10:30am &12:00 Noon DEVOTIONS - DEVOCIONES WEEKDAY EUCHARIST - MISAS DE LA SEMANA Miraculous Medal Novena: Mondays after the 9:00am mass. Monday thru Friday: 9:00am. Sacred Heart: Fridays after the 9:00am mass. Saturday: 9:00am. Adoration of the Blessed Sacrament:Thursdays 9:30am to Holidays: as announced in this bulletin. 11:45 am followed by Benediction. BAPTISM OF INFANTS LOS BAUTISMOS DE INFANTES. Is celebrated on the first Sunday of the month at 1:30 pm. Span- Seran celebrados en Espanol el Segundo Domingo del mes a la ish baptisms are celebrated on the second Sunday of the month 1:30 pm y en ingles, el primer Domingo del mes a la 1:30 pm. at 1:30 pm. Please call the Rectory to make an appointment to Por favor de, llamar a la rectoría para hacer una cita con un meet with one of the clergy and bring the child’s birth certificate miembro del clero y, de traer el certificado de nacimiento del to the appointment. -

Battle of White Plains Roster.Xlsx

Partial List of American Officers and Soldiers at the Battle of White Plains, October 28 - November 1, 1776 Name State DOB-DOD Rank Regiment 28-Oct Source Notes Abbot, Abraham MA ?-9/8/1840 Capt. Blake Dept. of Interior Abbott, Seth CT 12/23/1739-? 2nd Lieut. Silliman's Levies (1st Btn) Chatterton Hill Desc. Of George Abbott Capt. Hubble's Co. Abeel, James NY 5/12/1733-4/20/1825 Maj. 1st Independent Btn. (Lasher's) Center Letter from James Abeel to Robert Harper Acker, Sybert NY Capt. 6th Dutchess Co. Militia (Graham's) Chatterton Hill Acton 06 MA Pvt. Eleazer Brooks's Regiment Chatterton Hill Shattuck's 1835 History of LostConcord art, sent with wounded Acton 07 MA Eleazer Brooks's Regiment Chatterton Hill Shattuck's 1835 History of Concord Acton 08 MA Eleazer Brooks's Regiment Chatterton Hill Shattuck's 1835 History of Concord Acton 09 MA Eleazer Brooks's Regiment Chatterton Hill Shattuck's 1835 History of Concord Acton 10 MA Eleazer Brooks's Regiment Chatterton Hill Shattuck's 1835 History of Concord Acton 11 MA Eleazer Brooks's Regiment Chatterton Hill Shattuck's 1835 History of Concord Acton 12 MA Eleazer Brooks's Regiment Chatterton Hill Shattuck's 1835 History of Concord Acton 13 MA Eleazer Brooks's Regiment Chatterton Hill Shattuck's 1835 History of Concord Acton 14 MA Eleazer Brooks's Regiment Chatterton Hill Shattuck's 1835 History of Concord Adams, Abner CT 11/5/1735-8/5/1825 Find a Grave Ranger for Col. Putnam Adams, Abraham CT 12/2/1745-? Silliman's Levies (1st Btn) Chatterton Hill Rev War Rcd of Fairfield CTCapt Read's Co. -

The Haversack the Newsletter of the Sergeant Lawrence Everhart Chapter Maryland Society of the Sons of the American Revolution

Vol. 3 Issue 4 September, 2016 The Haversack The Newsletter of the Sergeant Lawrence Everhart Chapter Maryland Society of the Sons of the American Revolution st President’s Report meeting. Both 1 Vice President Pat Barron and 2nd Vice President Eugene Moyer are working dil- Greetings Compatriots: igently to produce a wonderful program that will, I’m very pleased to announce that our Chapter’s without a doubt, be interesting and enjoyable for partnership building and planning efforts for our all. very first social meeting with Maryland’s Lieuten- Donald A. Deering ant Governor Boyd K. Rutherford resulted in a President huge success. Approximately 100 attendees from Foundation Chair various businesses, local government, private non- Sergeant Lawrence Everhart Chapter profits and other organizations attended to meet the Maryland Society of the Sons of the American Lt. Governor and learn of Maryland’s proposals Revolution for growth and economic development. As an add- National Society of the Sons of the American ed highlight, the Lieutenant Governor was intro- Revolution duced by Maryland State Secretary of Veteran’s Affairs, George W. Ownings III, who, along with his son and two grandsons, was recently inducted 2016 SEMI-ANNUAL MEETING as an SAR member. We were also pleased to wel- come Frederick’s very first County Executive “Jan Gardner” who offered a brief presentation prior to The semi-annual meeting of the Sergeant Law- the Secretary’s introduction. rence Everhart chapter will be held at Dutch’s Daughter restaurant on Thursday, October 20, Our partners in this endeavor, who we hope to 2016, beginning with a social hour at 6:00 PM. -

Fort Greene Park Prospect Park

Page 2 New York City Department of Parks & Recreation's Page 2 Fort Greene Park Prospect Park Fort Greene Historic Walking Tours &/or History Programs All programs meet outside the Audubon Center. Every Saturday at 1 p.m. * 06/14 tour starts at noon Sat, 6/15, 11 a.m. – Father’s Day Fishing – Bring Dad out to the park for an afternoon of fishing with Sun, 6/08, 12 p.m. – Nuts about Squirrels- Enjoy a fun the kids. Poles and bait will be provided. afternoon learning about those nutty creatures. Sat, 6/21, 11 a.m.- Canoe the Lullwater- Join the Sat, 6/14, 12 p.m. - Fort Green Neighborhood Walking Rangers for canoeing . Arrive early; first come first Tour- Explore the rich history and architecture of this served. Canoe times to sign up for: 11 a.m., 12:30 p.m. historic district. Wear comfortable walking shoes. or 2 p.m. Sign-up starts at 10:30 a.m. Sun, 6/15, 1 p.m. – Fort Greene Trivia- Join us as we answer some great questions about the Park. What’s the Sun, 6/22, 12 p.m.- Explore the Ravine Hike- Join the tallest tree? How tall is the Monument? Urban Park Rangers for a guided walk through the Ravine. Sun, 6/22, 1 p.m. – History of Fort Greene-What’s so special about Fort Greene? How did it get it’s name? Sat, 6/28, 1 p.m.- Tree-mendous Walk- Join the Urban Come find out its history. Park Rangers for a guided tour of beautiful Prospect Park. -

Battle of Long Island - Wikipedia

Battle of Long Island - Wikipedia https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Long_Island Coordinates: 40°39′58″N 73°57′58″W From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia The Battle of Long Island is also known as the Battle of Brooklyn and the Battle of Brooklyn Heights. It was Battle of Long Island fought on August 27, 1776 and was the first major battle of Part of the American Revolutionary War the American Revolutionary War to take place after the United States declared its independence on July 4, 1776. It was a victory for the British Army and the beginning of a successful campaign that gave them control of the strategically important city of New York. In terms of troop deployment and fighting, it was the largest battle of the entire war. After defeating the British in the Siege of Boston on March 17, 1776, commander-in-chief General George Washington brought the Continental Army to defend the port city of New York, then limited to the southern end of Manhattan The Delaware Regiment at the Battle of Long Island Island. Washington understood that the city's harbor would Date August 27, 1776 provide an excellent base for the British Navy during the campaign, so he established defenses there and waited for Location Kings County, Long Island, New York the British to attack. In July, the British under the command 40°39′58″N 73°57′58″W of General William Howe landed a few miles across the Result British victory[1] harbor from Manhattan on the sparsely-populated Staten Island, where they were slowly reinforced by ships in Belligerents Lower New York Bay during the next month and a half, United States bringing their total force to 32,000 troops. -

The Battle of Brooklyn, August 27-29, 1776 a Walking Guide to Sites and Monuments

The Battle of Brooklyn, August 27-29, 1776 A Walking Guide to Sites and Monuments Old Stone House & Washington Park 336 Third Street between Fourth and Fifth Avenues P.O. Box 150613, Brooklyn, NY 11215 718.768.3195 www.theoldstonehouse.org Using This Guide This guide is offered as a means through which visi- Transportation Resources The following sites are in geographic proximity and can be tors may experience the 1776 Battle of Brooklyn as it Walking: Due to the immense area of the battlefield and the visited together. developed in the fields, orchards, creeks, and country long distances between some of the sites, a walking tour of all sites Sites 1, 21 (The British Landing at Gravesend, Mile- lanes that later became nearly invisible in Brooklyn’s is not very practical. Nearby sites and other attractions which are stone Park, New Utrecht Liberty Pole) densely inhabited nineteenth and twentieth century within walking distance (although here, too, distances might be too Sites 11, 12 (The Red Lion Inn,* Battle Hill in urban expansion. great for some walkers) are listed for each site. Point-to-point tran- Green-Wood Cemetery) It is intended to be much more than a requiem for sit/walking directions are available from www.hopstop.com. Sites 13, 15, 25 (Flatbush Pass/Battle Pass, Mount Car: the dead and wounded of the battle. Land use evolves Curbside parking is problematic in the extreme at some Prospect, Lefferts Homestead) over time, and Brooklyn offers a prism through which locations, easier in others, and easier in general on weekends and Sites 16, 22, 24 (Litchfield Villa, Old First Re- visitors may consider nearly four centuries of the chang- holidays. -

Report of an Archeological Survey at Red Bank Battlefield Park (Fort Mercer), National Park, Gloucester County, New Jersey

"IT IS PAINFUL FOR ME TO LOSE SO MANY GOOD PEOPLE" REPORT OF AN ARCHEOLOGICAL SURVEY AT RED BANK BATTLEFIELD PARK (FORT MERCER), NATIONAL PARK, GLOUCESTER COUNTY, NEW JERSEY PREPARED FOR GLOUCESTER COUNTY DEPARTMENT OF PARKS AND RECREATION PREPARED BY AMERICAN BATTLEFIELD PROTECTION PROGRAM GRANT GA--- COMMONWEALTH HERITAGE GROUP, INC. WEST CHESTER, PENNSYLVANIA +VOF ARPA COMPLIANT COPY "IT IS PAINFUL FOR ME TO LOSE SO MANY GOOD PEOPLE" Report of an Archeological Survey at Red Bank Battlefield Park (Fort Mercer), National Park, Gloucester County, New Jersey Prepared for Gloucester County Department of Parks and Recreation Prepared by Wade P. Catts, RPA Robert Selig, Ph.D. Elisabeth LaVigne, RPA Kevin Bradley, RPA Kathryn Wood and David Orr, Ph.D. American Battlefield Protection Program Grant GA-2287-14-004 Commonwealth Heritage Group, Inc. 535 N. Church Street West Chester, PA 19380 FINAL June 2017 This material is based upon work assisted by a grant from the Department of the Interior, National Park Service. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Department of the Interior ABSTRACT This report presents the goals, methods, and results of an historical and archeological survey at Red Bank Battlefield Park, a park owned and administered by Gloucester County, New Jersey. The Park commemorates the American Revolutionary War battle fought October 22, 1777, between the American defenders of Fort Mercer (remnants of which are located in the Park) and a reinforced Hessian brigade. The project was funded by the American Battlefield Protection Program (ABPP) and followed the guidelines established by the ABPP as well as those of the state of New Jersey. -

Blwt671-400 John Eccleston

Southern Campaign American Revolution Pension Statements and Rosters Bounty Land Claim for John Eccleston (Eggleston) BLWt671-400 Transcribed and annotated by C. Leon Harris. [Note: The federal file jacket labeled “John Eggleston” indicates that the subject of the file was a Major, and it bears the notation “Dated April 18 1794.” The file comprises only the correspondence transcribed below, which explains that John Eccleston’s surname was misspelled.] ST. JAMES HOTEL/ Hennepin Avenue at Second St./ MINNEAPOLIS, MINN. June 13, 1925, Chief of the Record and Pension Office War Department, Washington, D.C. Will you kindly furnish me with the official military record of Thomas Woolford, Dorchester County Maryland, who is said to have enlisted March 2, 1776, as Captain of the 6th Independent Maryland Company. Also of Thomas White, Dorchester Co. Said to be member of the 7th Company of Maryland Battalion, 1776. Also of John Eccleston, Dorchester Co. who is said to have been commissioned 1st Lieut 6th Independent company of Maryland Troops Jan. 5, 1776. Commissioned Captain 2nd Reg. Dec. 10, 1776. and Major Dec. 10, 1777. Respectfully Yours,/ Twiford E. Hughes, [signed] T. E. Hughes Address as above August 4, 1925 Twiford E. Hughes St. James Hotel Minneapolis, Minn. Sir: I have to advise you that from the records of this Bureau it appears that Warrant No. 671 for four hundred acres of bounty land was issued April 18, 1794 on account of the services of Major John Eggleston of the Maryland Line, War of the Revolution. There is no further data on file as to his services and no data on file as to his family, owing to the destruction of papers in such claims when the war Office was burned in November 1800.