Online Re-Creation Culture in the 21St Century

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pdf 611.37 K

Socio-Cultural and Technical Issues in Non-Expert Dubbing: A Case Study Christiane Nord1a, Masood Khoshsaligheh2b, Saeed Ameri3b Abstract ARTICLE HISTORY: Advances in computer sciences and the emergence of innovative technologies have entered numerous new Received November 2014 elements of change in translation industry, such as the Received in revised form February 2015 inseparable usage of software programs in audiovisual Accepted February 2015 translation. Initiated by the expanding reality of fandubbing Available online February 2015 in Iran, the present article aimed at illuminating this practice into Persian in the Iranian context to partly address the line of inquiries about fandubbing which still is an uncharted territory on the margins of Translation Studies. Considering the scarce research in this area, the paper aimed to provide data to attract more attention to the notion of fandubbing by KEYWORDS: providing real-world examples from a community with a language of limited diffusion. An exploratory review of a Non-expert dubbing large and diverse sample of openly accessed dubbed Fundubbing products into Persian, ranging from short-formed clips to Fandubbing feature movies, such dubbing practice was further classified Quasi-professional dubbing into fundubbing, fandubbing, and quasi-professional dubbing. User-generated translation Based on the results, the study attempted to describe the cultural aspects and technical features of each type. © 2015 IJSCL. All rights reserved. 1 Professor, Email: [email protected] 2 Assistant Professor, Email: [email protected] (Corresponding Author) Tel: +98-915-501-2669 3 MA Student, Email: [email protected] a University of the Free State, South Africa b Ferdowsi University of Mashhad, Iran 2 Socio-Cultural and Technical Issues in Non-Expert Dubbing: A Case Study 1. -

Teenie Weenie in a Too Big World: a Story for Fearful Children Free

FREE TEENIE WEENIE IN A TOO BIG WORLD: A STORY FOR FEARFUL CHILDREN PDF Margot Sunderland,Nicky Hancock,Nicky Armstrong | 32 pages | 03 Oct 2003 | Speechmark Publishing Ltd | 9780863884603 | English | Bicester, Oxon, United Kingdom ບິ ກິ ນີ - ວິ ກິ ພີ ເດຍ A novelty song is a type of song built upon some form of novel concept, such as a gimmicka piece of humor, or a sample of popular culture. Novelty songs partially overlap with comedy songswhich are more explicitly based on humor. Novelty songs achieved great popularity during the s and s. Novelty songs are often a parody or humor song, and may apply to a current event such as a holiday or a fad such as a dance or TV programme. Many use unusual Teenie Weenie in a Too Big World: A Story for Fearful Children, subjects, sounds, or instrumentation, and may not even be musical. It is based on their achievement Teenie Weenie in a Too Big World: A Story for Fearful Children a UK number-one single with " Doctorin' the Tardis ", a dance remix mashup of the Doctor Who theme music released under the name of 'The Timelords. Novelty songs were a major staple of Tin Pan Alley from its start in the late 19th century. They continued to proliferate in the early years of the 20th century, some rising to be among the biggest hits of the era. We Have No Bananas "; playful songs with a bit of double entendre, such as "Don't Put a Tax on All the Beautiful Girls"; and invocations of foreign lands with emphasis on general feel of exoticism rather than geographic or anthropological accuracy, such as " Oh By Jingo! These songs were perfect for the medium of Vaudevilleand performers such as Eddie Cantor and Sophie Tucker became well-known for such songs. -

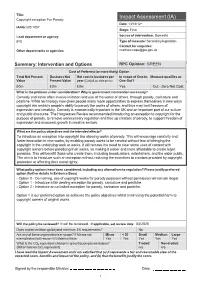

Copyright Exception for Parody Date: 13/12/12* IA No: BIS 1057 Stage: Final

Title: Impact Assessment (IA) Copyright exception For Parody Date: 13/12/12* IA No: BIS 1057 Stage: Final Lead department or agency: Source of intervention: Domestic IPO Type of measure: Secondary legislation Contact for enquiries: Other departments or agencies: [email protected] Summary: Intervention and Options RPC Opinion: GREEN Cost of Preferred (or more likely) Option Total Net Present Business Net Net cost to business per In scope of One-In, Measure qualifies as Value Present Value year (EANCB on 2009 prices) One-Out? £0m £0m £0m Yes Out - Zero Net Cost What is the problem under consideration? Why is government intervention necessary? Comedy and satire often involve imitation and use of the works of others, through parody, caricature and pastiche. While technology now gives people many more opportunities to express themselves in new ways copyright law restricts people's ability to parody the works of others, and thus may limit freedom of expression and creativity. Comedy is economically important in the UK and an important part of our culture and public discourse. The Hargreaves Review recommended introducing an exception to copyright for the purpose of parody, to remove unnecessary regulation and free up creators of parody, to support freedom of expression and economic growth in creative sectors. What are the policy objectives and the intended effects? To introduce an exception into copyright law allowing works of parody. This will encourage creativity and foster innovation in new works, by enabling parody works to be created without fear of infringing the copyright in the underlying work or works. It will remove the need to clear some uses of content with copyright owners before parodying their works, so making it easier and more affordable to create legal parodies. -

"WEIRD AL" YANKOVIC: POLKAS, PARODIES and the POWER of SATIRE by Chuck Miller Originally Published in Goldmine #514

"WEIRD AL" YANKOVIC: POLKAS, PARODIES AND THE POWER OF SATIRE By Chuck Miller Originally published in Goldmine #514 Al Yankovic strapped on his accordion, ready to perform. All he had to do was impress some talent directors, and he would be on The Gong Show, on stage with Chuck Barris and the Unknown Comic and Jaye P. Morgan and Gene Gene the Dancing Machine. "I was in college," said Yankovic, "and a friend and I drove down to LA for the day, and auditioned for The Gong Show. And we did a song called 'Mr. Frump in the Iron Lung.' And the audience seemed to enjoy it, but we never got called back. So we didn't make the cut for The Gong Show." But while the Unknown Co mic and Gene Gene the Dancing Machine are currently brain stumpers in 1970's trivia contests, the accordionist who failed the Gong Show taping became the biggest selling parodist and comedic recording artist of the past 30 years. His earliest parodies were recorded with an accordion in a men's room, but today, he and his band have replicated tracks so well one would think they borrowed the original master tape, wiped off the original vocalist, and superimposed Yankovic into the mix. And with MTV, MuchMusic, Dr. Demento and Radio Disney playing his songs right out of the box, Yankovic has reached a pinnacle of success and longevity most artists can only imagine. Alfred Yankovic was born in Lynwood, California on October 23, 1959. Seven years later, his parents bought him an accordion for his birthday. -

An Animated Comedy for 8-12 Year Olds 26 X 12Min SERIES

An animated comedy for 8-12 year olds 26 x 12min SERIES © 2014 MWP-RDB Thongs Pty Ltd, Media World Holdings Pty Ltd, Red Dog Bites Pty Ltd, Screen Australia, Film Victoria and the Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Whale Bay isis homehome toto thethe disaster-pronedisaster-prone ThongThong familyfamily andand toto Australia’sAustralia’s leastleast visitedvisited touristtourist attraction,attraction, thethe GiantGiant Thong.Thong. ButBut thatthat maymay bebe about to change, for all the wrong reasons... Series Synopsis ........................................................................3 Holden Character Guide....................................................4 Narelle Character Guide .................................................5 Trevor Character Guide....................................................6 Brenda Character Guide ..................................................7 Rerp/Kevin/Weedy Guide.................................................8 Voice Cast.................................................................................9 ...because it’s also home to Holden Thong, a 12-year-old with a wild imagination Creators ...................................................................................12 and ability to construct amazing gadgets from recycled scrap. Holden’s father Director’s‘ Statement..........................................................13 Trevor is determined to put Whale Bay on the map, any map. Trevor’s hare-brained tourist-attracting schemes, combined with Holden’s ill-conceived contraptions, -

Limitation Where Author Is First Owner of Copyright: Reversionary Interest in the Copyright Some Comments on Section 14 Of

1 LIMITATION WHERE AUTHOR IS FIRST OWNER OF COPYRIGHT: REVERSIONARY INTEREST IN THE COPYRIGHT SOME COMMENTS ON SECTION 14 OF THE CANADIAN COPYRIGHT ACT * LAURENT CARRIÈRE ROBIC, LLP LAWYERS , PATENT & TRADEMARK AGENTS Text of Section 1.0 Related Sections 2.0 Related Regulations 3.0 Prior Legislation 3.1 Corresponding Section in Prior Legislation 3.2 Legislative History 3.2.1 S.C. 1921, c. 24, s. 11(2) part and 11(3). 3.2.2 R.S.C. 1927, c. 32, s. 12(3) and (4). 3.2.3 3.2.3 R.S.C. 1952, c. 55, s. 12(5) & (6). 3.2.4 R.S.C. 1970, c. C-30, s. 12(5) & (6). 3.2.5 R.S.C. 1985, c. C-42, s. 14(1) & (2). 3.3 Transitional 3.3.1 S.C. 1999, c. 24, s. 55(3) 4.0 Purpose 5.0 Commentary 5.1 History 5.2 General 5.3 Applicability 5.3.1 Author first owner 5.3.2 “After June 4, 1921” 5.3.3 “Otherwise than by will” 5.4 Public Order 5.4.1 Agreement to the contrary 5.4.2 Contrary agreement void 5.4.3 Asset of the author’s estate 5.4.4 Permanent Damage to Reversionary Interest 5.5 Exception 5.5.1 Collective work 5.5.2 Licence © CIPS, 2003. * Lawyer and trade-mark agent, Laurent Carrière is a partner with ROBIC, LLP , a multidisciplinary firm of lawyers, patent and trademark agents. Published as part of a Robic’s Canadian Copyright Act Annotated (Carswell). -

Parody and Pastiche

Evaluating the Impact of Parody on the Exploitation of Copyright Works: An Empirical Study of Music Video Content on YouTube Parody and Pastiche. Study I. January 2013 Kris Erickson This is an independent report commissioned by the Intellectual Property Office (IPO) Intellectual Property Office is an operating name of the Patent Office © Crown copyright 2013 2013/22 Dr. Kris Erickson is Senior Lecturer in Media Regulation at the Centre ISBN: 978-1-908908-63-6 for Excellence in Media Practice, Bournemouth University Evaluating the impact of parody on the exploitation of copyright works: An empirical study of music (www.cemp.ac.uk). E-mail: [email protected] video content on YouTube Published by The Intellectual Property Office This is the first in a sequence of three reports on Parody & Pastiche, 8th January 2013 commissioned to evaluate policy options in the implementation of the Hargreaves Review of Intellectual Property & Growth (2011). This study 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 presents new empirical data about music video parodies on the online © Crown Copyright 2013 platform YouTube; Study II offers a comparative legal review of the law of parody in seven jurisdictions; Study III provides a summary of the You may re-use this information (excluding logos) free of charge in any format or medium, under the findings of Studies I & II, and analyses their relevance for copyright terms of the Open Government Licence. To view policy. this licence, visit http://www.nationalarchives.gov. uk/doc/open-government-licence/ or email: [email protected] The author is grateful for input from Dr. -

Contentious Comedy

1 Contentious Comedy: Negotiating Issues of Form, Content, and Representation in American Sitcoms of the Post-Network Era Thesis by Lisa E. Williamson Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Glasgow Department of Theatre, Film and Television Studies 2008 (Submitted May 2008) © Lisa E. Williamson 2008 2 Abstract Contentious Comedy: Negotiating Issues of Form, Content, and Representation in American Sitcoms of the Post-Network Era This thesis explores the way in which the institutional changes that have occurred within the post-network era of American television have impacted on the situation comedy in terms of form, content, and representation. This thesis argues that as one of television’s most durable genres, the sitcom must be understood as a dynamic form that develops over time in response to changing social, cultural, and institutional circumstances. By providing detailed case studies of the sitcom output of competing broadcast, pay-cable, and niche networks, this research provides an examination of the form that takes into account both the historical context in which it is situated as well as the processes and practices that are unique to television. In addition to drawing on existing academic theory, the primary sources utilised within this thesis include journalistic articles, interviews, and critical reviews, as well as supplementary materials such as DVD commentaries and programme websites. This is presented in conjunction with a comprehensive analysis of the textual features of a number of individual programmes. By providing an examination of the various production and scheduling strategies that have been implemented within the post-network era, this research considers how differentiation has become key within the multichannel marketplace. -

Monthly Review of the World Intellectual Property Organization

Published monthly Annual subscription : 145 Swiss francs Each monthly issue: 15 Swiss francs Copyright - ' year - No. 6 Monthly Review of the June 1988 World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) Contents NOTIFICATIONS CONCERNING TREATIES WIPO Convention. Accessions: Swaziland, Trinidad and Tobago 261 Madrid Convention. Accession: Peru 261 WIPO MEETINGS Photographic Works. Preparatory Document for and Report of the WIPO/Uncsco Committee of Governmental Experts ( Paris. April 18 to 22. 1988) 262 Third International Congress on the Protection of Intellectual Property (of Authors. Artists and Producers) (Lima. April 21 to 23. 1988) 282 STUDIES The Copyright Aspects of Parodies and Similar Works, by Andre Françon 283 CORRESPONDENCE Letter from Norway, by Fiirger Stuevold Lassen 288 ACTIVITIES OF OTHER ORGANIZATIONS International Copyright Society (INTERGU). Xlth Congress (Locamo. March 21 to 25. 1988) ' 300 BOOKS AND ARTICLES 301 CALENDAR OF MEETINGS 302 COPYRIGHT AND NEIGHBORING RIGHTS LAWS AND TREATIES (INSERT) Editor's Note SPAIN Law on Intellectual Property (No. 22. of November 11. 1987) {Articles 101 to 148 and Additional. Transitional and Repealed Provisions) Text 1-01 © WIPO 1988 Any reproduction of official notes or reports, articles and translations of laws or agreements, published ISSN 0010-8626 in this review, is authorized only with the prior consent of WIPO. NOTIFICATIONS CONCERNING TREATIES 261 Notifications Concerning Treaties WIPO Convention Accessions SWAZILAND The Government of Swaziland deposited, on of establishing its contribution towards the budget May 18, 1988, its instrument of accession to the of the WIPO Conference. Convention Establishing the World Intellectual The said Convention, as amended on October 2, Property Organization (WIPO), signed at Stock- 1979, will enter into force, with respect to Swazi- holm on July 14, 1967. -

Copyright Infringement of Musical Compositions: a Systematic Appproach E

The University of Akron IdeaExchange@UAkron Akron Law Review Akron Law Journals July 2015 Copyright Infringement of Musical Compositions: A Systematic Appproach E. Scott rF uehwald Please take a moment to share how this work helps you through this survey. Your feedback will be important as we plan further development of our repository. Follow this and additional works at: http://ideaexchange.uakron.edu/akronlawreview Part of the Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons, and the Intellectual Property Law Commons Recommended Citation Fruehwald, E. Scott (1993) C" opyright Infringement of Musical Compositions: A Systematic Appproach," Akron Law Review: Vol. 26 : Iss. 1 , Article 2. Available at: http://ideaexchange.uakron.edu/akronlawreview/vol26/iss1/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Akron Law Journals at IdeaExchange@UAkron, the institutional repository of The nivU ersity of Akron in Akron, Ohio, USA. It has been accepted for inclusion in Akron Law Review by an authorized administrator of IdeaExchange@UAkron. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Fruehwald: Copyright Infringement of Musical Compositions COPYRIGHT INFRINGEMENT OF MUSICAL COMPOSITIONS: A SYSTEMATIC APPROACH by E. SCoTr FRUEHWALD INTRODUCTION This article addresses the problems that courts face when dealing with copyright infringement of musical compositions. Infringement of music presents special problems for judges and juries because music is an intuitive art that is nonverbal and nonvisual. Consequently, traditional methods of establishing infringement are often unreliable when applied to music. This paper will concentrate on the question of whether a composition that is similar to, but not the same as, another work infringes on the other work. -

Copyright Policy Classification: Academic

Copyright Policy Classification: Academic Responsible Authority: Director, Academic Services & Learning Resources Executive Sponsor: Vice President Student Success Approval Authority: Board of Governors Date First Approved: January 8, 2014 Date Last Reviewed: January 8, 2014 Mandatory Review Date: May 1, 2020 PURPOSE This policy will: • Define acceptable use of material protected by copyright, • Outline the responsibilities of all users of copyright materials, • Help College employees and students comply with the legal requirements of the Copyright Act, and • Establish a framework for responsible practice. SCOPE This policy applies to all faculty, staff, and students of George Brown College. Excluded from the scope of this policy is: • The College’s ownership of copyright, patents (see the College Policy on Intellectual Property) • The ownership of copyright materials created by College academic employees (see the Academic Employees Collective Agreement) • The status of the College as an Internet Service Provider (ISP) This document is available in accessible format DEFINITIONS Any definitions listed below apply to this document only with no implied or intended institution-wide use. Word/Term Definition Academic Employees Used interchangeably with “faculty” to refer to full-time, partial-load, part-time, and sessional professors, instructors, counselors, and librarians. Accessible Media Consultant The Librarian within the Library Learning Commons of the Academic Services & Learning Resources Department who is responsible for the administration of the College’s Policy on Captioned Media and E- Text and for supporting faculty and staff with compliance. Authorization Used interchangeably with “permission” to refer to the consent of the copyright owner to allow someone to do something with a work (e.g. -

Dsti/Stp(2014)37

For Official Use DSTI/STP(2014)37 Organisation de Coopération et de Développement Économiques Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development 05-Nov-2014 ___________________________________________________________________________________________ _____________ English - Or. English DIRECTORATE FOR SCIENCE, TECHNOLOGY AND INNOVATION COMMITTEE FOR SCIENTIFIC AND TECHNOLOGICAL POLICY For Official Use Official For DSTI/STP(2014)37 LEGAL ASPECTS OF OPEN ACCESS TO PUBLICLY FUNDED RESEARCH CSTP Delegates are invited to provide comments on this document by 14 November 2014. In the absence of comments, or after the document has been revised in the light of comments, the document will be submitted for approval by written procedure and subsequently integrated into a report entitled "Inquiries into Intellectual Property's Economic Impact", which is part of the multidisciplinary OECD project entitled "New Sources of Growth: Knowledge-based Capital, Phase 2". Please submit comments and questions to Giulia Ajmone ([email protected]) by 14 November 2014. Contacts: Giulia Ajmone Marsan (STI/CSO); E-mail: [email protected]; Jeremy West (STI/DEP); E-mail: [email protected]; MarioCervantes (STI/CSO); E-mail: [email protected]; English JT03365628 Complete document available on OLIS in its original format - This document and any map included herein are without prejudice to the status of or sovereignty over any territory, to the delimitation of Or. English international frontiers and boundaries and to the name of any territory,