Women in Popular Music and the Construction of Authenticity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dickins' Sony Deal Opens New Chapter by Ajax Scott Rob Dickins Bas Teame Former Rival Sony Music Three Months After Leaving Warn

Dickins' Sony deal opens new chapter by Ajax Scott later building a team of up to 20. Rob Dickins bas teame Instant Karma will sign around five rA, ^ threeformer months rival Sony after Music leaving warner ri likelyartists to a be year, from most the UKof orwhom Ireland. are hisMusic music to launchindustry the career. next stage of Dickins says he will not specifically S Dickins' new record label Instant goclose chasing to expiring. after those Tm notacts. going If they to with the hasfirst got single off torelease a fiying under start the handling partnership Interscope - My releasesName Is inby the US UK they'reare interested going to in call," being he part says. of that therapper single, Eminem released - enjoying next Monday a huge initial(March shipout. 29), have Around been 220.000 ordered unitsby of months of negotiations between runningDickins, Warner's who spent UK ninepublishing years theretaiiefsVwhile Top 40 of the the Airplay track waschart. yesterday "Ifs appealing (Sunday) right on acrosscourse theto move board," into says Dickins, his lawyer Tony Russell arm before moving to head its Polydor head of radio promotionl" TU.Ruth ..U.._ Parrish. A V.UK promo visit will inelude wasand afinaliy list of whittled would-be down backers to Sony that New partners: Dickins (second isrecord in no company hurry toin 1983,issue addsrecords. he im_ rrShady LPes - thiswhich week debuted on The at Bignumber Breakfast twoThe in and the CD:UK.States earlierThe this (l-r)left) Sony in New Music York Worldwide last week with "Ifs really not important when the onth - follows on April 12. -

Lecture Outlines

CHAPTER FOURTEEN: “SMELLS LIKE TEEN SPIRIT”: HIP-HOP, “ALTERNATIVE” MUSIC, AND THE ENTERTAINMENT BUSINESS Lecture Outlines Lecture 1: Hip-Hop and Techno I. Hip-Hop Breaks Out (1980s–1990s) A. In the mid-1980s, rap moved into the popular mainstream. B. 1986 saw the release of the first two multiplatinum rap albums: 1. Raising Hell by Run-D.M.C. a) Number Three on Billboard’s pop albums chart b) Over three million copies sold 2. Licensed to Ill by the Beastie Boys a) Number One for seven weeks b) Over seven million copies sold 3. Expansion of the audience for hip-hop music was the key to the commercial success of these albums. a) Included millions of young white fans, attracted by the rebelliousness of the genre C. Both Raising Hell and Licensed to Ill were released on a new independent label called Def Jam. CHAPTER FOURTEEN: “SMELLS LIKE TEEN SPIRIT”: HIP-HOP, “ALTERNATIVE” MUSIC, AND THE ENTERTAINMENT BUSINESS 1. Co-founded in 1984 by the hip-hop promoter Russell Simmons and the musician-producer Rick Rubin 2. Cross-promoting a new generation of artists 3. Expanding and diversifying the national audience for hip-hop 4. In 1986, Def Jam became the first rap-oriented independent label to sign a distribution deal with one of the “Big Five” record companies, Columbia Records. D. Run-D.M.C. 1. Trio: a) MCs Run (Joseph Simmons, b. 1964) and D.M.C. (Darryl McDaniels, b. 1964) b) DJ Jam Master Jay (Jason Mizell, b. 1965) 2. Adidas Corporation and Run-D.M.C. -

Exploring Lesbian and Gay Musical Preferences and 'LGB Music' in Flanders

Observatorio (OBS*) Journal, vol.9 - nº2 (2015), 207-223 1646-5954/ERC123483/2015 207 Into the Groove - Exploring lesbian and gay musical preferences and 'LGB music' in Flanders Alexander Dhoest*, Robbe Herreman**, Marion Wasserbauer*** * PhD, Associate professor, 'Media, Policy & Culture', University of Antwerp, Sint-Jacobsstraat 2, 2000 Antwerp ([email protected]) ** PhD student, 'Media, Policy & Culture', University of Antwerp, Sint-Jacobsstraat 2, 2000 Antwerp ([email protected]) *** PhD student, 'Media, Policy & Culture', University of Antwerp, Sint-Jacobsstraat 2, 2000 Antwerp ([email protected]) Abstract The importance of music and music tastes in lesbian and gay cultures is widely documented, but empirical research on individual lesbian and gay musical preferences is rare and even fully absent in Flanders (Belgium). To explore this field, we used an online quantitative survey (N= 761) followed up by 60 in-depth interviews, asking questions about musical preferences. Both the survey and the interviews disclose strongly gender-specific patterns of musical preference, the women preferring rock and alternative genres while the men tend to prefer pop and more commercial genres. While the sexual orientation of the musician is not very relevant to most participants, they do identify certain kinds of music that are strongly associated with lesbian and/or gay culture, often based on the play with codes of masculinity and femininity. Our findings confirm the popularity of certain types of music among Flemish lesbians and gay men, for whom it constitutes a shared source of identification, as it does across many Western countries. The qualitative data, in particular, allow us to better understand how such music plays a role in constituting and supporting lesbian and gay cultures and communities. -

1. Summer Rain by Carl Thomas 2. Kiss Kiss by Chris Brown Feat T Pain 3

1. Summer Rain By Carl Thomas 2. Kiss Kiss By Chris Brown feat T Pain 3. You Know What's Up By Donell Jones 4. I Believe By Fantasia By Rhythm and Blues 5. Pyramids (Explicit) By Frank Ocean 6. Under The Sea By The Little Mermaid 7. Do What It Do By Jamie Foxx 8. Slow Jamz By Twista feat. Kanye West And Jamie Foxx 9. Calling All Hearts By DJ Cassidy Feat. Robin Thicke & Jessie J 10. I'd Really Love To See You Tonight By England Dan & John Ford Coley 11. I Wanna Be Loved By Eric Benet 12. Where Does The Love Go By Eric Benet with Yvonne Catterfeld 13. Freek'n You By Jodeci By Rhythm and Blues 14. If You Think You're Lonely Now By K-Ci Hailey Of Jodeci 15. All The Things (Your Man Don't Do) By Joe 16. All Or Nothing By JOE By Rhythm and Blues 17. Do It Like A Dude By Jessie J 18. Make You Sweat By Keith Sweat 19. Forever, For Always, For Love By Luther Vandros 20. The Glow Of Love By Luther Vandross 21. Nobody But You By Mary J. Blige 22. I'm Going Down By Mary J Blige 23. I Like By Montell Jordan Feat. Slick Rick 24. If You Don't Know Me By Now By Patti LaBelle 25. There's A Winner In You By Patti LaBelle 26. When A Woman's Fed Up By R. Kelly 27. I Like By Shanice 28. Hot Sugar - Tamar Braxton - Rhythm and Blues3005 (clean) by Childish Gambino 29. -

Helena Mace Song List 2010S Adam Lambert – Mad World Adele – Don't You Remember Adele – Hiding My Heart Away Adele

Helena Mace Song List 2010s Adam Lambert – Mad World Adele – Don’t You Remember Adele – Hiding My Heart Away Adele – One And Only Adele – Set Fire To The Rain Adele- Skyfall Adele – Someone Like You Birdy – Skinny Love Bradley Cooper and Lady Gaga - Shallow Bruno Mars – Marry You Bruno Mars – Just The Way You Are Caro Emerald – That Man Charlene Soraia – Wherever You Will Go Christina Perri – Jar Of Hearts David Guetta – Titanium - acoustic version The Chicks – Travelling Soldier Emeli Sande – Next To Me Emeli Sande – Read All About It Part 3 Ella Henderson – Ghost Ella Henderson - Yours Gabrielle Aplin – The Power Of Love Idina Menzel - Let It Go Imelda May – Big Bad Handsome Man Imelda May – Tainted Love James Blunt – Goodbye My Lover John Legend – All Of Me Katy Perry – Firework Lady Gaga – Born This Way – acoustic version Lady Gaga – Edge of Glory – acoustic version Lily Allen – Somewhere Only We Know Paloma Faith – Never Tear Us Apart Paloma Faith – Upside Down Pink - Try Rihanna – Only Girl In The World Sam Smith – Stay With Me Sia – California Dreamin’ (Mamas and Papas) 2000s Alicia Keys – Empire State Of Mind Alexandra Burke - Hallelujah Adele – Make You Feel My Love Amy Winehouse – Love Is A Losing Game Amy Winehouse – Valerie Amy Winehouse – Will You Love Me Tomorrow Amy Winehouse – Back To Black Amy Winehouse – You Know I’m No Good Coldplay – Fix You Coldplay - Yellow Daughtry/Gaga – Poker Face Diana Krall – Just The Way You Are Diana Krall – Fly Me To The Moon Diana Krall – Cry Me A River DJ Sammy – Heaven – slow version Duffy -

Congressional Record United States Th of America PROCEEDINGS and DEBATES of the 110 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 110 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION Vol. 153 WASHINGTON, MONDAY, JUNE 18, 2007 No. 98 House of Representatives The House met at 12:30 p.m. and was mismanagement, corruption, and a per- In this program, people receive an called to order by the Speaker pro tem- petual dependence upon foreign aid and overnight transfer from an American pore (Ms. HIRONO). remittances. Mexico must make tough bank account to a Mexican one. The f decisions and get its economy in shape. two central banks act as middlemen, Until then, Madam Speaker, we will taking a cut of about 67 cents no mat- DESIGNATION OF SPEAKER PRO continue to face massive immigration ter what the size of the transaction. TEMPORE from the south. According to Elizabeth McQuerry of The SPEAKER pro tempore laid be- While we are painfully aware of the the Federal Reserve, banks then typi- fore the House the following commu- problems illegal immigration is caus- cally charge $2.50 to $5 to transfer ing our society, consider what it is nication from the Speaker: about $350. In total, this new program doing to Mexico in the long run. The WASHINGTON, DC, cuts the costs of remittances by at June 18, 2007. massive immigration is draining many least half. In America, 200 banks are I hereby appoint the Honorable MAZIE K. villages across Mexico of their impor- now signed up for this service com- HIRONO to act as Speaker pro tempore on tant labor pool. -

American Express and Jagged Little Pill Present Special Livestream Event You Live, You Learn: a Night with Alanis Morissette and ‘Jagged Little Pill’

NEWS RELEASE American Express and Jagged Little Pill present special livestream event You Live, You Learn: A Night with Alanis Morissette and ‘Jagged Little Pill’ 5/19/2020 Today, American Express and Jagged Little Pill are pleased to present a special Facebook and YouTube livestream benet event, You Live, You Learn: A Night with Alanis Morissette and ‘Jagged Little Pill’ on Tuesday, May 19 at 8:00PM ET in support of the COVID-19 emergency relief eorts of The Actors Fund. The event will bring Cardmembers closer to the theatre experience they love and marks the rst of many virtual entertainment experiences Cardmembers can enjoy in the coming months. "Our Cardmembers’ lives have changed so much over the last few weeks and so have their plans when it comes to entertainment. American Express Experiences continues to be one of the most valuable and unique benets on our Cards and we remain committed to oering our Cardmembers exclusive access to theatre, concert and dining experiences even while at home,” said Megan McKee, Vice President & General Manager, Consumer Card Services, American Express Canada. “We know our Cardmembers are always on the lookout for special entertainment experiences and this livestream event marks a new way that we’ll bring those to life in a completely dierent environment.” The one-hour event features six exclusive performances from the Broadway cast of Jagged Little Pill and seven-time Grammy Award-winning songwriter and recording artist Alanis Morissette, who co-hosts the livestream with SafePlace International founder Justin Hilton. The event also includes conversations with cast members and special appearances by the show’s Oscar-winning writer Diablo Cody (Juno, Tully), Tony-winning director Diane Paulus (Waitress, Pippin), Olivier Award-winning choreographer Sidi Larbi Cherkaoui (Beyoncé at The Grammys; The Carters’ “Apesh*t”), and Pulitzer Prize winning orchestrator/arranger Tom Kitt (Next to Normal, American Idiot). -

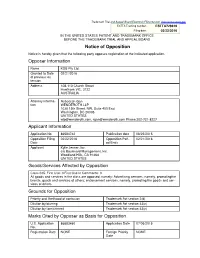

Objection To, Or Fault Found with Applicant’S Services Marketed Under

Trademark Trial and Appeal Board Electronic Filing System. http://estta.uspto.gov ESTTA Tracking number: ESTTA728619 Filing date: 02/22/2016 IN THE UNITED STATES PATENT AND TRADEMARK OFFICE BEFORE THE TRADEMARK TRIAL AND APPEAL BOARD Notice of Opposition Notice is hereby given that the following party opposes registration of the indicated application. Opposer Information Name KDB Pty Ltd. Granted to Date 02/21/2016 of previous ex- tension Address 108-110 Church Street Hawthorn VIC, 3122 AUSTRALIA Attorney informa- Rebeccah Gan tion WENDEROTH LLP 1030 15th Street, NW, Suite 400 East Washington, DC 20005 UNITED STATES [email protected], [email protected] Phone:202-721-8227 Applicant Information Application No 86584742 Publication date 08/25/2015 Opposition Filing 02/22/2016 Opposition Peri- 02/21/2016 Date od Ends Applicant Kylie Jenner, Inc. c/o Boulevard Management, Inc. Woodland Hills, CA 91364 UNITED STATES Goods/Services Affected by Opposition Class 035. First Use: 0 First Use In Commerce: 0 All goods and services in the class are opposed, namely: Advertising services, namely, promotingthe brands, goods and services of others; endorsement services, namely, promoting the goods and ser- vices of others Grounds for Opposition Priority and likelihood of confusion Trademark Act section 2(d) Dilution by blurring Trademark Act section 43(c) Dilution by tarnishment Trademark Act section 43(c) Marks Cited by Opposer as Basis for Opposition U.S. Application 86683460 Application Date 07/06/2015 No. Registration Date NONE Foreign Priority NONE Date Word Mark KYLIE MINOGUE DARLING Design Mark Description of NONE Mark Goods/Services Class 003. -

Vide O Clipe: Forças E Sensações No Caos

UNIVERSIDADE ESTADUAL DE CAMPINAS FACULDADE DE EDUCAÇÃO DISSERTAÇÃO DE MESTRADO Vide o clipe: forças e sensações no caos Autor: Pamela Zacharias Sanches Oda Orientador: Prof. Dr. Antonio Carlos Rodrigues de Amorim Este exemplar corresponde à redação final da Dissertação defendida por Pamela Zacharias Sanches Oda e aprovada pela Comissão Julgadora. Data: 15 / 02 / 2011 2011 ii iii Ao Lucas, Meu amor, amigo e companheiro, que possibilitou através de seu incentivo, de seu olhar crítico e de sua imensa paciência a concretização deste trabalho. iv AGRADECIMENTOS Agradecer é estar em estado de graça. Assim me sinto ao traçar as últimas linhas dessa dissertação. Nesse momento, rememoro todo o trajeto do mestrado e percebo que o que me trouxe aqui se iniciou bem antes da escrita do projeto, bem antes de fazer minha inscrição para o processo seletivo. O início de tudo está em um tempo não situável e deve-se a tantos corpos que não haveria espaço para agradecê-los nestas páginas. Por isso o estado de graça, a gratidão ampla e imensurável por estar onde estou e poder deixar um registro de um pedacinho de minha vida no mundo, mesmo que perdido entre as estantes de uma biblioteca acadêmica. Isso porque este texto é apenas a materialidade simbólica de tudo o que este trabalho me trouxe e vai além, muito além do que ele apresenta. Agradeço, portanto, ao prof. dr. Antônio Carlos de Amorim, por ter se interessado em me orientar e ter me possibilitado tantos encontros teóricos e principalmente humanos; ao grupo de pesquisa OLHO e, em especial ,ao Humor -

ENTERTAINMENT WEEKLY Interview for Not Making It Clear That He Wasn't the Father of the Baby She Miscarried Last May

Love's Story The combative singer-actress embarks on a legal skirmish with her record label that may change what it means to be a rock star. Oh, and she also has some choice words about her late husband's bandmates, her newfound ancestry, Russell Crowe, Angelina Jolie... By Holly Millea | Mar 25, 2002 Image credit: Courtney Love Photographs by Jean Baptiste Mondino COURTNEY LOVE IS IN A LIMOUSINE TAKING HER FROM Los Angeles to Desert Hot Springs on a detox mission. "I've been on a bit of a bender after 9/11," she admits. "I've got a lot of s--- in me. I weigh 147 pounds." Which is why she's checking into the We Care colonic spa for five days of fasting. Slumped low in the seat, the 37-year-old actress and lead singer of Hole is wearing baggy faded jeans, a brown pilled sweater, and Birkenstock sandals, her pink toenails twinkling with rhinestones. On her head is a wool knit hat - 1 - that looks like something she found on the street. Last night she sat for three hours while her auburn hair extensions were unglued and cut out. "See?" Love says, pulling the cap off. "I look like a Dr. Seuss character on chemo." She does. Her hair is short and tufty and sticking out in all directions. It's a disaster. Love smiles a sad, self-conscious smile and covers up again. Lighting a cigarette, she asks, "Why are we doing this story? I don't have a record or a movie to promote. -

Sly & Robbie – Primary Wave Music

SLY & ROBBIE facebook.com/slyandrobbieofficial Imageyoutube.com/channel/UC81I2_8IDUqgCfvizIVLsUA not found or type unknown en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sly_and_Robbie open.spotify.com/artist/6jJG408jz8VayohX86nuTt Sly Dunbar (Lowell Charles Dunbar, 10 May 1952, Kingston, Jamaica, West Indies; drums) and Robbie Shakespeare (b. 27 September 1953, Kingston, Jamaica, West Indies; bass) have probably played on more reggae records than the rest of Jamaica’s many session musicians put together. The pair began working together as a team in 1975 and they quickly became Jamaica’s leading, and most distinctive, rhythm section. They have played on numerous releases, including recordings by U- Roy, Peter Tosh, Bunny Wailer, Culture and Black Uhuru, while Dunbar also made several solo albums, all of which featured Shakespeare. They have constantly sought to push back the boundaries surrounding the music with their consistently inventive work. Dunbar, nicknamed ‘Sly’ in honour of his fondness for Sly And The Family Stone, was an established figure in Skin Flesh And Bones when he met Shakespeare. Dunbar drummed his first session for Lee Perry as one of the Upsetters; the resulting ‘Night Doctor’ was a big hit both in Jamaica and the UK. He next moved to Skin Flesh And Bones, whose variations on the reggae-meets-disco/soul sound brought them a great deal of session work and a residency at Kingston’s Tit For Tat club. Sly was still searching for more, however, and he moved on to another session group in the mid-70s, the Revolutionaries. This move changed the course of reggae music through the group’s work at Joseph ‘Joe Joe’ Hookim’s Channel One Studio and their pioneering rockers sound. -

Art. Music. Games. Life. 16 09

ART. MUSIC. GAMES. LIFE. 16 09 03 Editor’s Letter 27 04 Disposed Media Gaming 06 Wishlist 07 BigLime 08 Freeware 09 Sonic Retrospective 10 Alexander Brandon 12 Deus Ex: Invisible War 20 14 Game Reviews Music 16 Kylie Showgirl Tour 18 Kylie Retrospective 20 Varsity Drag 22 Good/Bad: Radio 1 23 Doormat 25 Music Reviews Film & TV 32 27 Dexter 29 Film Reviews Comics 31 Death Of Captain Marvel 32 Blankets 34 Comic Reviews Gallery 36 Andrew Campbell 37 Matthew Plater 38 Laura Copeland 39 Next Issue… Publisher/Production Editor Tim Cheesman Editor Dan Thornton Deputy Editor Ian Moreno-Melgar Art Editor Andrew Campbell Sub Editor/Designer Rachel Wild Contributors Keith Andrew/Dan Gassis/Adam Parker/James Hamilton/Paul Blakeley/Andrew Revell Illustrators James Downing/Laura Copeland Cover Art Matthew Plater [© Disposable Media 2007. // All images and characters are retained by original company holding.] dm6/editor’s letter as some bloke once mumbled. “The times, they are You may have spotted a new name at the bottom of this a-changing” column, as I’ve stepped into the hefty shoes and legacy of former Editor Andrew Revell. But luckily, fans of ‘Rev’ will be happy to know he’s still contributing his prosaic genius, and now he actually gets time to sleep in between issues. If my undeserved promotion wasn’t enough, we’re also happy to announce a new bi-monthly schedule for DM. Natural disasters and Acts of God not withstanding. And if that isn’t enough to rock you to the very foundations of your soul, we’re also putting the finishing touches to a newDisposable Media website.