Exploring Lesbian and Gay Musical Preferences and 'LGB Music' in Flanders

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Krt Madonna Knight Ridder/Tribune

FOLIO LINE FOLIO LINE FOLIO LINE “Music” “Ray of Light” “Something to Remember” “Bedtime Stories” “Erotica” “The Immaculate “I’m Breathless” “Like a Prayer” “You Can Dance” (2000; Maverick) (1998; Maverick) (1995; Maverick) (1994; Maverick) (1992; Maverick) Collection”(1990; Sire) (1990; Sire) (1989; Sire) (1987; Sire) BY CHUCK MYERS Knight Ridder/Tribune Information Services hether a virgin, vamp or techno wrangler, Madon- na has mastered the public- image makeover. With a keen sense of what will sell, she reinvents herself Who’s That Girl? and transforms her music in Madonna Louise Veronica Ciccone was ways that mystify critics and generate fan interest. born on Aug. 16, 1958, in Bay City, Mich. Madonna staked her claim to the public eye by challenging social norms. Her public persona has Oh Father evolved over the years, from campy vixen to full- Madonna’s father, Sylvio, was a design en- figured screen siren to platinum bombshell to gineer for Chrysler/General Dynamics. Her leather-clad femme fatale. Crucifixes, outerwear mother, Madonna, died of breast cancer in undies and erotic fetishes punctuated her act and 1963. Her father later married Joan Gustafson, riled critics. a woman who had worked as the Ciccone Part of Madonna’s secret to success has been family housekeeper. her ability to ride the music video train to stardom. The onetime self-professed “Boy Toy” burst onto I’ve Learned My Lesson Well the pop music scene with a string of successful Madonna was an honor roll student at music video hits on MTV during the 1980s. With Adams High School in Rochester, Mich. -

The Uk's Top 200 Most Requested Songs in 1980'S

The Uk’s top 200 most requested songs in 1980’s 1. Billie Jean - Michael Jackson 2. Into the Groove - Madonna 3. Super Freak Part I - Rick James 4. Beat It - Michael Jackson 5. Funkytown - Lipps Inc. 6. Sweet Dreams (Are Made of This) - Eurythmics 7. Don't You Want Me? - Human League 8. Tainted Love - Soft Cell 9. Like a Virgin - Madonna 10. Blue Monday - New Order 11. When Doves Cry - Prince 12. What I Like About You - The Romantics 13. Push It - Salt N Pepa 14. Celebration - Kool and The Gang 15. Flashdance...What a Feeling - Irene Cara 16. It's Raining Men - The Weather Girls 17. Holiday - Madonna 18. Thriller - Michael Jackson 19. Bad - Michael Jackson 20. 1999 - Prince 21. The Way You Make Me Feel - Michael Jackson 22. I'm So Excited - The Pointer Sisters 23. Electric Slide - Marcia Griffiths 24. Mony Mony - Billy Idol 25. I'm Coming Out - Diana Ross 26. Girls Just Wanna Have Fun - Cyndi Lauper 27. Take Your Time (Do It Right) - The S.O.S. Band 28. Let the Music Play - Shannon 29. Pump Up the Jam - Technotronic feat. Felly 30. Planet Rock - Afrika Bambaataa and The Soul Sonic Force 31. Jump (For My Love) - The Pointer Sisters 32. Fame (I Want To Live Forever) - Irene Cara 33. Let's Groove - Earth, Wind, and Fire 34. It Takes Two (To Make a Thing Go Right) - Rob Base and DJ EZ Rock 35. Pump Up the Volume - M/A/R/R/S 36. I Wanna Dance With Somebody (Who Loves Me) - Whitney Houston 37. -

GREG KURSTIN Her

ISSUE #26 MMUSICMAG.COM ISSUE #26 MMUSICMAG.COM PRODUCER How was it producing Kelly Clarkson? they’d be flawless. Other than layering and She can really sing, that’s for sure. She’s adding in harmonies, I don’t think there cool, professional and easy to work with. was any vocal editing. She’ll do a few takes to get warmed up and after that, you’re getting awesome take after How did you produce Tegan and Sara? awesome take. We did some vocal comping, They’ve been making records for a while but nothing extensive. and wanted to expand their sound and try something different. They had heard a lot of What’s the story behind the megahit music that I had worked on and reached out “Stronger (What Doesn’t Kill You)”? to me. A lot of their demos felt very synth- I was both the producer and a songwriter, based, and being a synth nerd, I got excited. but there was a somewhat finished version We ended up doing eight songs together. I of that song that existed before I came into played everything except for drums on the the picture. It was slower, and the chords record. I love their songwriting and I’m proud and feel of the track were different from the of what we did. version that was released. The label wasn’t convinced it would work for her. I had Kelly Clarkson What about producing the Flaming Lips? previously worked with Kelly on “Honestly” I had played with the Lips, and sometime and it went really well, so her A&R played as possible. -

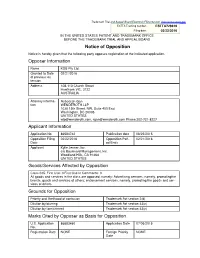

Objection To, Or Fault Found with Applicant’S Services Marketed Under

Trademark Trial and Appeal Board Electronic Filing System. http://estta.uspto.gov ESTTA Tracking number: ESTTA728619 Filing date: 02/22/2016 IN THE UNITED STATES PATENT AND TRADEMARK OFFICE BEFORE THE TRADEMARK TRIAL AND APPEAL BOARD Notice of Opposition Notice is hereby given that the following party opposes registration of the indicated application. Opposer Information Name KDB Pty Ltd. Granted to Date 02/21/2016 of previous ex- tension Address 108-110 Church Street Hawthorn VIC, 3122 AUSTRALIA Attorney informa- Rebeccah Gan tion WENDEROTH LLP 1030 15th Street, NW, Suite 400 East Washington, DC 20005 UNITED STATES [email protected], [email protected] Phone:202-721-8227 Applicant Information Application No 86584742 Publication date 08/25/2015 Opposition Filing 02/22/2016 Opposition Peri- 02/21/2016 Date od Ends Applicant Kylie Jenner, Inc. c/o Boulevard Management, Inc. Woodland Hills, CA 91364 UNITED STATES Goods/Services Affected by Opposition Class 035. First Use: 0 First Use In Commerce: 0 All goods and services in the class are opposed, namely: Advertising services, namely, promotingthe brands, goods and services of others; endorsement services, namely, promoting the goods and ser- vices of others Grounds for Opposition Priority and likelihood of confusion Trademark Act section 2(d) Dilution by blurring Trademark Act section 43(c) Dilution by tarnishment Trademark Act section 43(c) Marks Cited by Opposer as Basis for Opposition U.S. Application 86683460 Application Date 07/06/2015 No. Registration Date NONE Foreign Priority NONE Date Word Mark KYLIE MINOGUE DARLING Design Mark Description of NONE Mark Goods/Services Class 003. -

D'eurockéennes

25 ans d’EUROCKÉENNES LE CRÉDIT AGRICOLE FRANCHE-COMTÉ NE VOUS LE DIT PAS SOUVENT : IL EST LE PARTENAIRE INCONTOURNABLE DES ÉVÉNEMENTS FRANCs-COMTOIS. IL SOUTIENT Retrouvez le Crédit Agricole Franche-Comté, une banque différente, sur : www.ca-franchecomte.fr Caisse Régionale de Crédit Agricole Mutuel de Franche-Comté - Siège social : 11, avenue Elisée Cusenier 25084 Besançon Cedex 9 -Tél. 03 81 84 81 84 - Fax 03 81 84 82 82 - www.ca-franchecomte.fr - Société coopérative à capital et personnel variables agréée en tant qu’établissement de crédit - 384 899 399 RCS Besançon - Société de courtage d’assurance immatriculée au Registre des Intermédiaires en Assurances sous le n° ORIAS 07 024 000. ÉDITO SOMMAIRE La fête • 1989 – 1992 > Naissance d’un festival > L’excellence et la tolérance, François Zimmer .......................................................p.4 > Une grosse aventure, Laurent Arnold ...................................................................p.5 continue > « Caomme un pèlerinage », Laurent Arnold ........................................................p.6 Les Eurockéennes ont 25 ans. Qui l’eut > Un air de Woodstock au pied du Ballon d’Alsace, Thierry Boillot .......................p.7 cru ? Et si aujourd’hui en 2013, un doux • 1993 – 1997 > Les Eurocks, place incontournable rêveur déposait sur la table le dossier d’un grand et beau festival de musiques > Les Eurocks, précurseurs du partenariat, Lisa Lagrange ..................................... p.8 actuelles (selon la formule consacrée), > Internet : le partenariat de -

A7fgleefaklatit" "

HOT DANCE/ELECTRONIC SONGSTM DANCE/ELECTRONIC ALBUMST" LIST TITLECERTIFICATION Artist LAST I THIS ARTISTCERTIFICATION MEEK PRODUCER (SONGWRITER) IMPRINT/PROMOTION IABEL WEEK WEER IMPRINT/DISTRIBUTING LABEL (HART NEW LA ROUX Trouble In Paradise j LATCHA Disclosure Featuring Sam Smith I 4S IE4OGISINCHLIqTIPILMIENDA M POSTOOR/CHERWIREE/INTERSCOPEAGA 0 DKUOSUKOILLITISCEGLARTENCESSINININNIEN 2 2 LINDSEY STIRLING Shatter Me 13 In SUMMERS Calvin Harris , 20 LINDSEYSTOmP 0 (MARRS KAMM TUN. DECONSTRUCTION/ELY MANTRA/ROC NAROMOLUMBIA DISCLOSURE Settle 60 TURN DOWN FOR WHAT DJ Snake &cLoiLlulop lO ME IHOO/PMR/04RRYIRE 17iNTF RSCOPF /oGA 3 3 3 A 33 DI SRAM .I.SMII H (1.14.94114.W.GRKAHOSE.M. BIUSSO) A1 LADY GAGA ARTPOP 37 RATHER BE STREAMLINE/IA.5(0PC/. Clean Bandit Featuring Jess Glynne 4 25 O 0 0 01111JRATIERSONA.CHATTO (LNANERAPMTERSON.N.MARSHALL) BIG BEAT/RRP DAFT PUNKARandom Access Memories 63 5 DAFT LIFE/COLUMBIA BREAK FREE AsLA,.......arih,Aoirtiaza Grande Featuring 4 4 O La Roux ZEDOMAx MARTIN (A2 0 0 C DEADMAUS while(1<2) 6 A SKY FULL OF STARS Coldplay TAAUSTRAP/ASTRALWERXSKAINTOL 6 4 0 0 WOURNIAPIPPNRUNTILIANIONNEARAPINNUIWIEWILILDAWIDUAIWRWIN,IN me.otoPt N.LL, Finds AVICII True 45 WASTED Tiesto Featuring Matthew Koma 0 PRMONSLAND 6 7 7 5 14 ILIEWIMILUIESTOMOR1STACINDIRWIVIUNESULAWKIKG4S1 NAM INIDNIVIINAAWERICASIPN, `Paradise' SYLVAN ESSO Sylvan Esso 11 8 PARTISAN HIDEAWAY Kiesza O R.SAFUNI IK.R.ELLESTAD.R.SAFUNI) LORAL LEGENDNITH . BROADWAWISUND/REPUBUC 8 14 La Roux follows its 0 0 12 KIESZA Hideaway (EP) 3 0 LONA LEGENDATHR BROADWAY/614ND Grammy -winning self -titled 8 9 DARE (LA LA LA) Shakira 5 18 Di LK.SoauSAR.CR4IGHIARAISNOUKIRLUANOLPRIPTEALLINAITIXXIIMNARINEGIRWICIDL Al NA debut with its first No.1 10 SKRILLEX Recess 19 BEAT/OWSLA/ATLANTKAG onDance/Electronic WAVES Mr. -

Bad Habit Song List

BAD HABIT SONG LIST Artist Song 4 Non Blondes Whats Up Alanis Morissette You Oughta Know Alanis Morissette Crazy Alanis Morissette You Learn Alanis Morissette Uninvited Alanis Morissette Thank You Alanis Morissette Ironic Alanis Morissette Hand In My Pocket Alice Merton No Roots Billie Eilish Bad Guy Bobby Brown My Prerogative Britney Spears Baby One More Time Bruno Mars Uptown Funk Bruno Mars 24K Magic Bruno Mars Treasure Bruno Mars Locked Out of Heaven Chris Stapleton Tennessee Whiskey Christina Aguilera Fighter Corey Hart Sunglasses at Night Cyndi Lauper Time After Time David Guetta Titanium Deee-Lite Groove Is In The Heart Dishwalla Counting Blue Cars DNCE Cake By the Ocean Dua Lipa One Kiss Dua Lipa New Rules Dua Lipa Break My Heart Ed Sheeran Blow BAD HABIT SONG LIST Artist Song Elle King Ex’s & Oh’s En Vogue Free Your Mind Eurythmics Sweet Dreams Fall Out Boy Beat It George Michael Faith Guns N’ Roses Sweet Child O’ Mine Hailee Steinfeld Starving Halsey Graveyard Imagine Dragons Whatever It Takes Janet Jackson Rhythm Nation Jessie J Price Tag Jet Are You Gonna Be My Girl Jewel Who Will Save Your Soul Jo Dee Messina Heads Carolina, Tails California Jonas Brothers Sucker Journey Separate Ways Justin Timberlake Can’t Stop The Feeling Justin Timberlake Say Something Katy Perry Teenage Dream Katy Perry Dark Horse Katy Perry I Kissed a Girl Kings Of Leon Sex On Fire Lady Gaga Born This Way Lady Gaga Bad Romance Lady Gaga Just Dance Lady Gaga Poker Face Lady Gaga Yoü and I Lady Gaga Telephone BAD HABIT SONG LIST Artist Song Lady Gaga Shallow Letters to Cleo Here and Now Lizzo Truth Hurts Lorde Royals Madonna Vogue Madonna Into The Groove Madonna Holiday Madonna Border Line Madonna Lucky Star Madonna Ray of Light Meghan Trainor All About That Bass Michael Jackson Dirty Diana Michael Jackson Billie Jean Michael Jackson Human Nature Michael Jackson Black Or White Michael Jackson Bad Michael Jackson Wanna Be Startin’ Something Michael Jackson P.Y.T. -

The Medic Droid Into the Groove

Into The Groove The Medic Droid And you can dance for inspiration Set me up a line, I'm waiting Get into the groove Boy you've got to prove your love to me, yeah Get up on your feet, yeah step to the beat Boy what will it be? Music can be such a revelation Dancing around, you feel the sweet sensation We might be lovers if the rhythm's right I hope this feeling never ends tonight Only when I'm dancing can I feel this free At night I lock the doors, where no one else can see I'm tired of dancing here all by myself Tonight I wanna dance with someone else Get into the groove Boy you've got to prove your love to me, yeah Get up on your feet, yeah step to the beat Boy what will it be? Gonna get to know you in a special way This doesn't happen to me every day Don't try to hide it, love wears no disguise I see the fire burning in your eyes Only when I'm dancing can I feel this free At night I lock the doors, where no one else can see I'm tired of dancing here all by myself Tonight I wanna dance with someone else Get into the groove Boy you've got to prove your love to me, yeah Get up on your feet, yeah step to the beat Boy what will it be? Live out your fantasies here with me Just let the music set you free Touch my body now and move in time Now I know you're mine, you've got to Live, live, live, live, live, live, live Live out your fantasies here with me Just let the music set you free Touch my body now and move in time Now I know you're mine Get into the groove Boy you've got to prove your love to me, yeah Get up on your feet, yeah step to the beat Boy what will it be? Get into the groove Boy you've got to prove your love to me, yeah Get up on your feet, yeah step to the beat Boy what will it be? Get into the groove Boy you've got to prove your love to me, yeah Get up on your feet, yeah step to the beat Boy what will it be? Tištěno z pisnicky-akordy.cz Sponzor: www.srovnavac.cz - vyberte si pojištění online! Powered by TCPDF (www.tcpdf.org). -

Venustheatre

VENUSTHEATRE Dear Member of the Press: Thank you so much for coverage of The Speed Twins by Maureen Chadwick. I wanted to cast two women who were over 60 to play Ollie and Queenie. And, I'm so glad I was able to do that. This year, it's been really important for me to embrace comedy as much as possible. I feel like we all probably need to laugh in this crazy political climate. Because I thought we were losing this space I thought that this show may be the last for me and for Venus. It turns out the new landlord has invited us to stay and so, the future for Venus is looking bright. There are stacks of plays waiting to be read and I look forward to spending the summer planning the rest of the year here at Venus. This play is a homage, in some ways, to The Killing of Sister George. I found that script in the mid-nineties when it was already over 30 years old and I remember exploring it and being transformed by the archetypes of female characters. To now be producing Maureen's play is quite an honor. She was there! She was at the Gateway. She is such an impressive writer and this whole experience has been very dierent for Venus, and incredibly rewarding. I hope you enjoy the show. All Best, Deborah Randall Venus Theatre *********************************************** ABOUT THE PLAYWRIGHT PERFORMANCES: receives about 200 play submissions and chooses four to produce in the calendar year ahead. Each VENUSTHEATRE Maureen Chadwick is the creator and writer of a wide range of award-winning, critically acclaimed and May 3 - 27, 2018 production gets 20 performances. -

In the Transition from Stage to Arena, Live Music Is Remade

Intimate live girls Halligan, B Title Intimate live girls Authors Halligan, B Type Book Section URL This version is available at: http://usir.salford.ac.uk/id/eprint/33518/ Published Date 2015 USIR is a digital collection of the research output of the University of Salford. Where copyright permits, full text material held in the repository is made freely available online and can be read, downloaded and copied for non-commercial private study or research purposes. Please check the manuscript for any further copyright restrictions. For more information, including our policy and submission procedure, please contact the Repository Team at: [email protected]. Intimate Live Girls Benjamin Halligan Keywords: aura, intimacy, kissing, authenticity, liveness, social media, spectacle, Miley Cyrus, Katy Perry, Terry Richardson, Peter Gabriel Abstract: The arena concert requires a particular type of liveness of performance in order to transcend impersonal mass entertainment. Liveness here looks to authenticity and happenstance, privileges personal communications and seeks to live in the moment, and in this way the live performance then meets and matches or even surpasses the virtual life of the artist or group. The concert must be both mass spectacle and an individual and singular experience for those witnessing and participating in it. Without these latter essential attributes, which can be read as the auratic and authentic replacing the virtual, the arena concert falls short of ontological expectations of live music. In recent years the mise-en-scène of the arena concert has become calibrated to female artists with, seemingly, a concomitant feminisation of the event. In this, the space is often given over to intimacy, empathy, and presented as an insight into the life, and even philosophy, of the performer. -

Places to Go, People To

Hanson mistakenINSIDE EXCLUSIVE:for witches, burned. VerThe Vanderbilt Hustler’s Arts su & Entertainment Magazine s OCTOBER 28—NOVEMBER 3, 2009 VOL. 47, NO. 23 VANDY FALL FASHION We found 10 students who put their own spin on this season’s trends. Check it out when you fl ip to page 9. Cinematic Spark Notes for your reading pleasure on page 4. “I’m a mouse. Duh!” Halloween costume ideas beyond animal ears and hotpants. Turn to page 8 and put down the bunny ears. PLACES TO GO, PEOPLE TO SEE THURSDAY, OCTOBER 29 FRIDAY, OCTOBER 30 SATURDAY, OCTOBER 31 The Regulars The Black Lips – The Mercy Lounge Jimmy Hall and The Prisoners of Love Reunion Show The Avett Brothers – Ryman Auditorium THE RUTLEDGE The Mercy Lounge will play host to self described psychedelic/ There really isn’t enough good to be said about an Avett Brothers concert. – 3rd and Lindsley 410 Fourth Ave. South 37201 comedy band the Black Lips. With heavy punk rock infl uence and Singing dirty blues and southern rock with an earthy, roots The energy, the passion, the excitement, the emotion, the talent … all are 782-6858 mildly witty lyrics, these Lips are not Flaming but will certainly music sound, Jimmy Hall and his crew stick to the basics with completely unrivaled when it comes to the band’s explosive live shows. provide another sort of entertainment. The show will lean towards a songs like “Still Want To Be Your Man.” The no nonsense Whether it’s a heart wrenchingly beautiful ballad or a hard-driving rock punk or skaa atmosphere, though less angry. -

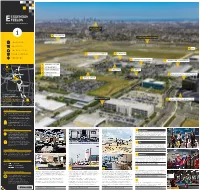

Essendon Fields Precinct – Hyatt Place Melbourne

insert cover positional here MELBOURNE CBD about this 15 minutes box size 10% Transparency of your 16 DFO ESSENDON cover artwork Tullamarine Freeway & CityLink TRA N S P O R T A BOUT U S 15 iFLY THINGS TO D O F OOD & DRINK 6 ESSENDON FIELDS AIRPORT 7 GYMNASIUM S ERVICE S 9 ESSENDON FIELDS CENTRAL 12 LAMANNA CAFÉ & SUPERMARKET ue ven 1 THE HUNGRY FOX CAFÉ ve A Hargra Bristol Street 2 CAR DEALERSHIPS MELBOURNE AIRPORT 3 FLIGHT EXPERIENCES 8 CHILDCARE 11 DENTIST 7km* 4 AIRWAYS MUSEUM 13 HYATT PLACE HOTEL & EVENTS CENTRE CYCLING TRAIL 5 BOUNCE INC. TRAM STOP 56 10 MEDICAL CENTRE English Street ESSENDON STATION oad Nomad R levard kin Bou Lar ESSENDON FIELDS IS WELL CONNECTED TO BOTH THE BUSINESS DISTRICT MELBOURNE CBD AND 14 MR MCCRACKEN RESTAURANT & BAR MELBOURNE AIRPORT MELBOURNE CBD 10km* Public Transport The free EF Station Shuttle operates from Essendon Fields to Essendon Train Station. Every weekday departing on the half hour between 7.15 – 9.30am & 4.15 – 6.30pm. Tram service 59 is a short walk from EF. Stop 56 (Airport West), located on Matthews Ave/ Earl Street departs every 8 minutes. Myki available from EF Newsagency. Airport Transit 16 DFO Essendon The free airport shuttle bus operates on- DFO Essendon comprises over 110 outlet retailers including demand daily between Essendon Fields Polo Ralph Lauren, Hugo Boss, Ted Baker and Coach. The Airport and Melbourne Airport between adjacent Homemaker Hub comprises over 20 stores. 6.00am and 10.00pm. Visit ef.com.au/ 100 Bulla Road, Essendon airportshuttle for booking details.