In the Transition from Stage to Arena, Live Music Is Remade

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Read PDF « Miles to Go / UUBWYW5DAQTI

HWVMXUPMCMNM > Doc ~ Miles to Go Miles to Go Filesize: 7.4 MB Reviews The ideal publication i ever read through. It is writter in simple words and never hard to understand. Your daily life span is going to be convert once you full looking over this ebook. (Tanner Willms PhD) DISCLAIMER | DMCA FURCKLOSABOL / Doc < Miles to Go MILES TO GO To get Miles to Go eBook, remember to follow the web link under and download the ebook or gain access to additional information that are relevant to MILES TO GO ebook. Disney Hyperion, 2009. Book Condition: New. Brand New, Unread Copy in Perfect Condition. A+ Customer Service! Summary: "There are multiple sides to all of us. Who we are and who we might be if we follow our dreams." -Miley Cyrus Three years ago, Miley Cyrus was a virtual unknown. Her life in rural Tennessee was filled with family, friends, school, cheerleading, and the daily tasks of living on a farm. And then came a little show called Hannah Montana . Almost overnight, Miley would rocket to superstardom, becoming a television and singing phenomenon. Quiet days were replaced with sold-out concerts, television appearances, and magazine shoots. But through it all, Miley has remained close to her family and friends and has stayed connected to the Southern roots that made her so strong. In Miles to Go, Miley oers an honest, humorous, and oen touching story of one girl's coming-of-age--from private moments with her pappy to o-roading with her dad, Billy Ray, to her run-ins with mean girls. -

Négociations Fondation Maeght : Entre Célébrations Monaco - Union Européenne Et Polémique R 28240 - F : 2,50 € Michel Roger S’Explique

FOOT : SANS FALCAO ET JAMES, QUELLES AMBITIONS POUR L’ASM ? 2,50 € Numéro 135 - Septembre 2014 - www.lobservateurdemonaco.mc SOCIÉTÉ USINE D’INCINÉRATION : LES SCÉNARIOS POSSIBLES ECOLOGIE CHANGEMENT CLIMATIQUE : POURQUOI IL FAUT RÉAGIR CULTURE NÉGOCIATIONS FONDATION MAEGHT : ENTRE CÉLÉBRATIONS MONACO - UNION EUROPÉENNE ET POLÉMIQUE R 28240 - F : 2,50 € MICHEL ROGER S’EXPLIQUE 3 782824 002503 01350 pour lui Solavie pag Observateur 09/2014.indd 2 08/09/14 15:51 LA PHOTO DU MOIS CRAINTES epuis des mois, dans certains milieux, on ne parle que de ça. En principauté, le lancement des négociations avec l’Union européenne (UE) inquiète pas mal de monde. Notamment les professions libérales qui craignent Dde voir tomber le presque total monopole qu’ont les Monégasques sur ces professions très encadrées réglementairement. « Ceci entraînerait à très court terme la disparition de notre profession telle qu’elle existe depuis des siècles. Ce qui est très préoccupant. D’autant plus que ce sera la même chose pour les médecins, les architectes, les experts-comptables monégasques… », a expliqué à L’Obs’ le bâtonnier de l’ordre des avocats de Monaco, Me Richard Mullot. Une crainte qui a poussé les avocats, les dentistes, les médecins et les architectes à se réunir pour réfléchir à la création d’un collectif. Objectif : défendre auprès du gou- vernement leurs positions et leurs spécificités qui restent propres à chaque profession. En face, le gouvernement cherche à rassurer. Dans l’interview qu’il a accordée à L’Obs’, le ministre d’Etat, Michel Roger, le répète. Il est hors de ques - tion de brader ce qui a fait le succès de la princi- pauté : « Il n’y aura pas d’accord si Monaco devait perdre sa souveraineté ou si ses spécificités devaient être menacées. -

Exploring Lesbian and Gay Musical Preferences and 'LGB Music' in Flanders

Observatorio (OBS*) Journal, vol.9 - nº2 (2015), 207-223 1646-5954/ERC123483/2015 207 Into the Groove - Exploring lesbian and gay musical preferences and 'LGB music' in Flanders Alexander Dhoest*, Robbe Herreman**, Marion Wasserbauer*** * PhD, Associate professor, 'Media, Policy & Culture', University of Antwerp, Sint-Jacobsstraat 2, 2000 Antwerp ([email protected]) ** PhD student, 'Media, Policy & Culture', University of Antwerp, Sint-Jacobsstraat 2, 2000 Antwerp ([email protected]) *** PhD student, 'Media, Policy & Culture', University of Antwerp, Sint-Jacobsstraat 2, 2000 Antwerp ([email protected]) Abstract The importance of music and music tastes in lesbian and gay cultures is widely documented, but empirical research on individual lesbian and gay musical preferences is rare and even fully absent in Flanders (Belgium). To explore this field, we used an online quantitative survey (N= 761) followed up by 60 in-depth interviews, asking questions about musical preferences. Both the survey and the interviews disclose strongly gender-specific patterns of musical preference, the women preferring rock and alternative genres while the men tend to prefer pop and more commercial genres. While the sexual orientation of the musician is not very relevant to most participants, they do identify certain kinds of music that are strongly associated with lesbian and/or gay culture, often based on the play with codes of masculinity and femininity. Our findings confirm the popularity of certain types of music among Flemish lesbians and gay men, for whom it constitutes a shared source of identification, as it does across many Western countries. The qualitative data, in particular, allow us to better understand how such music plays a role in constituting and supporting lesbian and gay cultures and communities. -

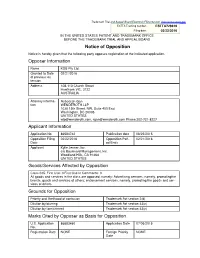

Objection To, Or Fault Found with Applicant’S Services Marketed Under

Trademark Trial and Appeal Board Electronic Filing System. http://estta.uspto.gov ESTTA Tracking number: ESTTA728619 Filing date: 02/22/2016 IN THE UNITED STATES PATENT AND TRADEMARK OFFICE BEFORE THE TRADEMARK TRIAL AND APPEAL BOARD Notice of Opposition Notice is hereby given that the following party opposes registration of the indicated application. Opposer Information Name KDB Pty Ltd. Granted to Date 02/21/2016 of previous ex- tension Address 108-110 Church Street Hawthorn VIC, 3122 AUSTRALIA Attorney informa- Rebeccah Gan tion WENDEROTH LLP 1030 15th Street, NW, Suite 400 East Washington, DC 20005 UNITED STATES [email protected], [email protected] Phone:202-721-8227 Applicant Information Application No 86584742 Publication date 08/25/2015 Opposition Filing 02/22/2016 Opposition Peri- 02/21/2016 Date od Ends Applicant Kylie Jenner, Inc. c/o Boulevard Management, Inc. Woodland Hills, CA 91364 UNITED STATES Goods/Services Affected by Opposition Class 035. First Use: 0 First Use In Commerce: 0 All goods and services in the class are opposed, namely: Advertising services, namely, promotingthe brands, goods and services of others; endorsement services, namely, promoting the goods and ser- vices of others Grounds for Opposition Priority and likelihood of confusion Trademark Act section 2(d) Dilution by blurring Trademark Act section 43(c) Dilution by tarnishment Trademark Act section 43(c) Marks Cited by Opposer as Basis for Opposition U.S. Application 86683460 Application Date 07/06/2015 No. Registration Date NONE Foreign Priority NONE Date Word Mark KYLIE MINOGUE DARLING Design Mark Description of NONE Mark Goods/Services Class 003. -

A Student's Guide to Study Abroad in Brussels

A STUDENT’S GUIDE TO STUDY ABROAD IN BRUSSELS Prepared by the Center for Global Education CONTENTS Section 1: Nuts and Bolts 1.1 Contact Information & Emergency Contact Information 1.2 Program Participant List 1.3 Term Calendar 1.4 Passport & Visas 1.5 Power of Attorney/Medical Release 1.6 International Student Identity Card 1.7 Register to Vote 1.8 Travel Dates/Group Arrival 1.9 Orientation 1.10 What to Bring Section 2: Studying & Living Abroad 2.1 Academics Abroad 2.2 Money and Banking 2.3 Housing and Meals Abroad 2.4 Service Abroad 2.5 Email Access 2.6 Travel Tips Section 3: All About Culture 3.1 Experiential Learning: What it’s all about 3.2 Adjusting to a New Culture 3.3 Culture Learning: Customs and Values Section 4: Health and Safety 4.1 Safety Abroad: A Framework 4.2 Health Care and Insurance 4.3 Women’s Issues Abroad 4.4 HIV 4.5 Drugs 4.6 Traffic 4.7 Politics 4.8 Voting by Absentee Ballot Section 5: Coming Back 5.1 Registration & Housing 5.2 Reentry and Readjustment SECTION 1: Nuts and Bolts 1.1 CONTACT INFORMATION PROGRAM DIRECTOR IN BRUSSELS Dr. Virginie Goffaux Study Abroad Director Vesalius College Mailing address: Pleinlaan 2 1050 Brussels, Belgium Visiting Address: Triomflaan 32 1160 Brussels, Belgium Email: [email protected] Tel: +32 2 629 28 26 Cell: + 32 496 10 97 51 Fax: +32 2 880 12 51 24/7 Emergency cell phone: +32 473 881 221 CONTACT FOR HOUSING ISSUES Note: when dialing from the U.S. -

Shaking the Trees Free

FREE SHAKING THE TREES PDF Azra Tabassum | 74 pages | 25 Jun 2014 | Words Dance Publishing | 9780692232408 | English | United States Shaking the Viral Tree It was remastered with most of Gabriel's catalogue in The tracks are creatively re-ordered, ignoring chronology. Some of the tracks were different from the album versions. New parts were recorded for several tracks in Gabriel's Real World Studios. Most songs are edited for time, either Shaking the Trees radio, single, or video edit versions. The remix is similar to the remix, which appeared as the B-side of the "Walk Through the Fire" single, but is edited down to 3m 45s long, as here. This version is a piano and voice arrangement, that Shaking the Trees far simpler than the highly produced version on Peter Gabriel Its sparseness is closer to the version that Gabriel recorded with Robert Fripp on Fripp's Exposure In interviews, Gabriel has said that he preferred the version, and it was that version with Fripp that he chose to overdub in German as the flipside of the single "Biko" released before Ein deutsches Album Although this album highlights songs from Peter Gabriel's earlier albums, tracks from Peter Gabriel II, or Scratch and the soundtrack to the film Birdy are not included. Say Anything Although Shaking the Trees made "In Your Eyes" perhaps the most well known Peter Gabriel song aside from " Sledgehammer ", it failed to crack the Shaking the Trees 20 and was thus omitted from the album in Shaking the Trees of five of the other eight tracks from So —four other hits and album track "Mercy Street". -

Avid Congratulates Its Many Customers Nominated for the 57Th Annual GRAMMY(R) Awards

December 10, 2014 Avid Congratulates Its Many Customers Nominated for the 57th Annual GRAMMY(R) Awards Award Nominees Created With the Company's Industry-Leading Music Solutions Include Beyonce's Beyonce, Ed Sheeran's X, and Pharrell Williams' Girl BURLINGTON, Mass., Dec. 10, 2014 (GLOBE NEWSWIRE) -- Avid® (Nasdaq:AVID) today congratulated its many customers recognized as award nominees for the 57th Annual GRAMMY® Awards for their outstanding achievements in the recording arts. The world's most prestigious ceremony for music excellence will honor numerous artists, producers and engineers who have embraced Avid EverywhereTM, using the Avid MediaCentral Platform and Avid Artist Suite creative tools for music production. The ceremony will take place on February 8, 2015 at the Staples Center in Los Angeles, California. Avid audio professionals created Record of the Year and Song of the Year nominees Stay With Me (Darkchild Version) by Sam Smith, Shake It Off by Taylor Swift, and All About That Bass by Meghan Trainor; and Album of the Year nominees Morning Phase by Beck, Beyoncé by Beyoncé, X by Ed Sheeran, In The Lonely Hour by Sam Smith, and Girl by Pharrell Williams. Producer Noah "40" Shebib scored three nominations: Album of the Year and Best Urban Contemporary Album for Beyoncé by Beyoncé, and Best Rap Song for 0 To 100 / The Catch Up by Drake. "This is my first nod for Album Of The Year, and I'm really proud to be among such elite company," he said. "I collaborated with Beyoncé at Jungle City Studios where we created her track Mine using their S5 Fusion. -

Sports Eye Protection for Men, Women & Youth

2017 ® Our vision is protecting yours. Sports Eye Protection for Men, Women & Youth ® BANGERZ® SPORTZ, A DIVISION OF HALO Sports®, IS A RECOGNIZED LEADER IN THE natIONAL MOVEMENT to EDUCate AND PROMOTE THE AWARENESS OF EYE SAFETY FOR SCHOLASTIC, RECreatIONAL, AND EXTREME sports. BANGERZ® SPORTZ ENGINEERS PRODUCTS to HELP PROTECT THE EYE FROM THE IMpaCT OF A BALL OR OTHER sport GEAR, AS WELL AS AN OPPONENT’S HANDS OR ELBOWS that POSE A threat to AN athLETE’S VISUAL SAFETY. WE OFFER A COMPLETE SELECTION OF sport SPECIFIC EYEGUARDS AND HIGH IMpaCT EYEWEAR WITH shatter RESIstant NON-PRESCRIPTION LENSES FOR ACTIVE PEOPLE OF ALL AGES. FOR OVER 30 YEARS HALO Sports® HAS EARNED ITS LEGENDARY REPUtatION FOR CRAFTING CertIFIED PROTECTIVE EYEWEAR. OUR RECS SPECS® BRAND IS THE NUMBER ONE SELLING COLLECTION OF ASTM APPROVED PRESCRIP- TION sport GOGGLES IN THE WORLD BANGERZ® SPORTZ... OUR VISION IS PROTECTING YOURS WHY WEAR BANGERZ SPORTZ EYE PROTECTION? HERE ARE THE FACTS • AN ESTIMateD 2.4 MILLION EYE INJURIES OCCUR IN THE US EACH YEAR • MORE THAN 600,000 ARE DOCUMENTED EYE INJURIES RELateD to sports AND RECreatION • 42,000 OF THESE INJURIES ARE OF A SEVERITY that REQUIRES EMERGENCY ROOM attentION • IT IS ESTIMATED that EACH YEAR 13,500 LEGALLY BLINDING sports EYE INJURIES OCCUR • NEARLY 1 MILLION AMERICANS HAVE LOST SOME DEGREE OF SIGHT DUE to EYE INJURY • EYE INJURY IS THE LEADING CAUSE OF MONOCULAR BLINDNESS • Sports PartICIpants USING EYEWEAR OR SUNWEAR that DOES NOT CONFORM to ASTM PROTECTION stanDARDS ARE at A FAR MORE SEVERE RISK OF EYE INJURY THAN partICIpants USING NO EYE PROTECTION at ALL. -

Khalid Teenage Dream Album Download DOWNLOAD ALBUM: Passenger – Songs for the Drunk and Broken Hearted (Deluxe) ZIP

khalid teenage dream album download DOWNLOAD ALBUM: Passenger – Songs for the Drunk and Broken Hearted (Deluxe) ZIP. DOWNLOAD Passenger Songs for the Drunk and Broken Hearted (Deluxe) ZIP & MP3 File. Ever Trending Star drops this amazing song titled “Passenger – Songs for the Drunk and Broken Hearted (Deluxe) Album“, its available for your listening pleasure and free download to your mobile devices or computer. You can Easily Stream & listen to this new “ FULL ALBUM: Passenger – Songs for the Drunk and Broken Hearted (Deluxe) Zip File” free mp3 download” 320kbps, cdq, itunes, datafilehost, zip, torrent, flac, rar zippyshare fakaza Song below. DOWNLOAD ZIP/MP3. Full Album Tracklist. 1. Sword from the Stone (03:21) 2. Tip of My Tongue (03:01) 3. What You’re Waiting For (02:37) 4. The Way That I Love You (02:39) 5. Remember to Forget (03:38) 6. Sandstorm (05:01) 7. A Song for the Drunk and Broken Hearted (03:59) 8. Suzanne (04:15) 9. Nothing Aches Like a Broken Heart (04:16) 10. London in the Spring (03:01) 11. London in the Spring (Acoustic) (02:56) 12. Nothing Aches Like a Broken Heart (Acoustic) (03:17) 13. Suzanne (Acoustic) (04:05) 14. A Song for the Drunk and Broken Hearted (Acoustic) (03:56) 15. Sandstorm (Acoustic) (04:10) 16. Remember to Forget (Acoustic) (03:36) 17. The Way That I Love You (Acoustic) (02:37) 18. What You’re Waiting For (Acoustic) (02:36) 19. Tip of My Tongue (Acoustic) (03:00) 20. Sword from the Stone (Acoustic) (03:33) Songs for the Drunk and Broken Hearted (Deluxe) Album by Passenger. -

AXS TV Canada Schedule for Mon. December 21, 2015 to Sun

AXS TV Canada Schedule for Mon. December 21, 2015 to Sun. December 27, 2015 Monday December 21, 2015 7:00 PM ET / 4:00 PM PT 8:00 AM ET / 5:00 AM PT Rock Legends New York City Drone Film Festival Eric Clapton - Rock Legends Eric Clapton tells the story of one of Britain’s enduring rock stars, The New York City Drone Film Festival is the first and only festival exclusively dedicated to drone featuring insights from music critics and showcasing classic music videos. cinema. In order to qualify for the festival the films must be shot 50% or more with a drone and be less than 5 minutes in length. In the new and exploding world of drone cinematography, 7:30 PM ET / 4:30 PM PT these are the best drone films in the world. Rock Legends Rod Stewart - Rod Stewart took to the blues circuit early in his career and became the first solo 9:00 AM ET / 6:00 AM PT artist to achieve the number 1 position in both the US and the UK after releasing his 3rd album, Rudy Maxa’s World Every Picture Tells A Story. Rock Legends Rod Stewart tells the story of one of Britain’s enduring Edinburgh & the Scottish Highlands - A special episode featuring the Edinburgh International rock stars. Festival. 8:00 PM ET / 5:00 PM PT 9:30 AM ET / 6:30 AM PT Big Head Todd and the Monsters: Sister Sweetly 20th Anniversary Celebration The Big Interview Big Head Todd and the Monsters celebrate the 20th anniversary of their album Sister Sweetly David Simon - One of Hollywood’s hottest screenwriters is a former newspaper reporter. -

Viol D'une Fillette À Genlis

PAGE 7 PORTES OUVERTES ENQUÊTE Samedis 24 et 31 mars Viol d’une fillette à Genlis : € -500 € Tous les 5000 la gendarmerie dessaisie d’achat* MTM • Fenêtres PVC • Volets roulants • Vérandas CHENÔVE & 03.80.52.14.15 855224600 Édition Région dijonnaise 21C Vendredi 23 mars 2018 - 1,10 € CHARREY-SUR-SAÔNE SOCIAL Le centre d’action sociale a été dissous Une première PAGE 18 COLLONGES-LÈS-PREMIÈRES charge D’importants travaux bientôt terminés ■ Photo Philippe PINGET PAGE 15 SELONGEY Le Département partenaire de la commune ■ La manifestation a réuni, hier à Dijon, près de 3 000 personnes. Photo Stéphane RAK PAGES 2, 3, 26 ET 27 PAGE 20 3e EDITION Marché couvert rue Thurot Mah Jong. Design Hans Hopfer. 24 25 MARS Habillé de tissus dessinés par Kenzo Takada. 5, rue du Platane - DIJON/QUETIGNY 873220400 880652900 02 VENDREDI 23 MARS 2018 LE BIEN PUBLIC CÔTE-D’OR SOCIAL Près de 3 000 personnes pour défendre la fonction publique Hier après-midi, dans les rues de Dijon, entre 2 800 et 3 400 personnes ont manifesté pour défendre les services publics, l’emploi et le pouvoir d’achat. algré la pluie, ce sont entre M2 800 personnes (selon la poli- ce) et 3 400 (selon la CGT) qui ont manifesté, hier, à partir de 14 h 30, place de la Libération à Dijon, pour la défense de la fonction publique. Ceci à l’appel de l’intersyndicale CFTC-CGC-CGT-FAFP-FO-FSU- Solidaires. Ce mouvement faisait suite à la mobilisation du 10 octo- bre, qui avait réuni entre 2 000 et 2 100 personnes à Dijon. -

Strut, Sing, Slay: Diva Camp Praxis and Queer Audiences in the Arena Tour Spectacle

Strut, Sing, Slay: Diva Camp Praxis and Queer Audiences in the Arena Tour Spectacle by Konstantinos Chatzipapatheodoridis A dissertation submitted to the Department of American Literature and Culture, School of English in fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Faculty of Philosophy Aristotle University of Thessaloniki Konstantinos Chatzipapatheodoridis Strut, Sing, Slay: Diva Camp Praxis and Queer Audiences in the Arena Tour Spectacle Supervising Committee Zoe Detsi, supervisor _____________ Christina Dokou, co-adviser _____________ Konstantinos Blatanis, co-adviser _____________ This doctoral dissertation has been conducted on a SSF (IKY) scholarship via the “Postgraduate Studies Funding Program” Act which draws from the EP “Human Resources Development, Education and Lifelong Learning” 2014-2020, co-financed by European Social Fund (ESF) and the Greek State. Aristotle University of Thessaloniki I dress to kill, but tastefully. —Freddie Mercury Table of Contents Acknowledgements...................................................................................i Introduction..............................................................................................1 The Camp of Diva: Theory and Praxis.............................................6 Queer Audiences: Global Gay Culture, the Arena Tour Spectacle, and Fandom....................................................................................24 Methodology and Chapters............................................................38 Chapter 1 Times