Archival Search for Felt Reports for the Alaska Earthquake of August 27, 1904

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

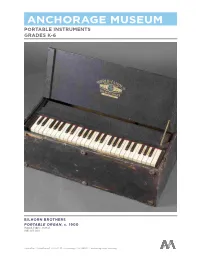

Anchorage Museum Portable Instruments Grades K-6

ANCHORAGE MUSEUM PORTABLE INSTRUMENTS GRADES K-6 BILHORN BROTHERS PORTABLE ORGAN, c. 1900 Wood, fabric, metal 1981.012.001 Education Department • 625 C St. Anchorage, AK 99501 • anchoragemuseum.org ACTIVITY AT A GLANCE Learn about portable instruments. Look closely at a portable reed organ from the late 1800s/early 1900s. Learn more about the organ and its owner. Listen to a video of a similar organ being played and learn more about how the instrument works. Brainstorm and sketch a portable instrument. Investigate other portable instruments in the Anchorage Museum collection. Create an instrument from recycled materials. PORTABLE ORGAN Begin by looking closely at the portable organ made by the Bilhorn Brothers company. If investigating the portable organ with another person, use the questions below to guide your discussions. If working alone, consider recording thoughts on paper: CLOSE-LOOKING Look closely, quietly at the organ for a few minutes. OBSERVE Share your observations about the organ or record your initial thoughts ASK • What do I notice about the organ? • What colors and materials does the artist use? • What sounds might the organ create? • What does it remind you of? • What more do you see? • What more can you find? DISCUSS USE 20 Questions Deck for more group discussion questions about the organ. LEARN MORE ABOUT THE MANUFACTURER Peter Philip Bilhorn was a well-known evangelist singer and composer who invented a portable reed organ to support his musical endeavors. With the support of his brother, George Bilhorn, he founded Bilhorn Brothers Organ Company of Chicago in 1885. Bilhorn Brothers manufactured portable reed organs, including the World-Famous Folding Organ in the Anchorage Museum collection. -

Iditarod National Historic Trail I Historic Overview — Robert King

Iditarod National Historic Trail i Historic Overview — Robert King Introduction: Today’s Iditarod Trail, a symbol of frontier travel and once an important artery of Alaska’s winter commerce, served a string of mining camps, trading posts, and other settlements founded between 1880 and 1920, during Alaska’s Gold Rush Era. Alaska’s gold rushes were an extension of the American mining frontier that dates from colonial America and moved west to California with the gold discovery there in 1848. In each new territory, gold strikes had caused a surge in population, the establishment of a territorial government, and the development of a transportation system linking the goldfields with the rest of the nation. Alaska, too, followed through these same general stages. With the increase in gold production particularly in the later 1890s and early 1900s, the non-Native population boomed from 430 people in 1880 to some 36,400 in 1910. In 1912, President Taft signed the act creating the Territory of Alaska. At that time, the region’s 1 Iditarod National Historic Trail: Historic Overview transportation systems included a mixture of steamship and steamboat lines, railroads, wagon roads, and various cross-country trail including ones designed principally for winter time dogsled travel. Of the latter, the longest ran from Seward to Nome, and came to be called the Iditarod Trail. The Iditarod Trail today: The Iditarod trail, first commonly referred to as the Seward to Nome trail, was developed starting in 1908 in response to gold rush era needs. While marked off by an official government survey, in many places it followed preexisting Native trails of the Tanaina and Ingalik Indians in the Interior of Alaska. -

Highlights for Fiscal Year 2013: Denali National Park

Highlights for FY 2013 Denali National Park and Preserve (* indicates action items for A Call to Action or the park’s strategic plan) This year was one of changes and challenges, including from the weather. The changes started at the top, with the arrival of new Superintendent Don Striker in January 2013. He drove across the country to Alaska from New River Gorge National River in West Virginia, where he had been the superintendent for five years. He also served as superintendent of Mount Rushmore National Memorial (South Dakota) and Fort Clatsop National Memorial (Oregon) and as special assistant to the Comptroller of the National Park Service. Some of the challenges that will be on his plate – implementing the Vehicle Management Plan, re-bidding the main concession contract, and continuing to work on a variety of wildlife issues with the State of Alaska. Don meets Skeeter, one of the park’s sled dogs The park and its partners celebrated a significant milestone, the centennial of the first summit of Mt. McKinley, with several activities and events. On June 7, 1913, four men stood on the top of Mt. McKinley, or Denali as it was called by the native Koyukon Athabaskans, for the first time. By achieving the summit of the highest peak in North America, Walter Harper, Harry Karstens, Hudson Stuck, and Robert Tatum made history. Karstens would continue to have an association with the mountain and the land around it by becoming the first Superintendent of the fledgling Mt. McKinley National Park in 1921. *A speaker series featuring presentations by five Alaskan mountaineers and historians on significant Denali mountaineering expeditions, premiered on June 7thwith an illustrated talk on the 1913 Ascent of Mt. -

Systematic Review of Prevalence of Young Child Overweight And

SYSTEMATIC REVIEW Systematic Review of Prevalence of Young Child Overweight and Obesity in the United States–Affiliated Pacific Region Compared With the 48 Contiguous States: The Children’s Healthy Living Program We estimated overweight Rachel Novotny, PhD, Marie Kainoa Fialkowski, PhD, Fenfang Li, PhD, Yvette Paulino, PhD, Donald Vargo, PhD, and obesity (OWOB) prev- Rally Jim, MO, Patricia Coleman, BS, Andrea Bersamin, PhD, Claudio R. Nigg, PhD, Rachael T. Leon Guerrero, alence of children in US- PhD, Jonathan Deenik, PhD, Jang Ho Kim, PhD, and Lynne R. Wilkens, DrPH Affiliated Pacific jurisdic- tions (USAP) of the Children’s THERE ARE FEW DATA ON Hawaii was 33% (13% over- Study Selection Healthy Living Program com- overweight and obesity (OWOB) weight and 20% obese) and the Peer-reviewed literature. For our pared with the contiguous fi United States. of children in the US-Af liated risk for OWOB varied by eth- primary data sources, we searched fi We searched peer-reviewed Paci c Islands, Hawaii, and nicity,from2-foldinAsiansto electronic databases (PubMed, literature and government Alaska, collectively referred to as 17-fold in Samoans, compared US National Library of Medicine; 8,9 reports (January 2001–April the US-Affiliated Pacific region with Whites. Data from the EBSCO Publishing; and Web of 2014) for OWOB prevalence (USAP) in this article (Figure A, Commonwealth of the Northern Science) for articles published be- of children aged 2 to 8 years available as a supplement to the Mariana Islands (CNMI) showed tween January 2001 and April in the USAP and found 24 online version of this article at similar OWOB prevalence.10 2014 with the following search sources. -

Annual Mountaineering Summary: 2013

Annual Mountaineering Summary: 2013 Celebrating a Century of Mountaineering on Denali Greetings from the recently re-named Walter Harper Talkeetna Ranger Station. With the September 2013 passage of the "Denali National Park Improvement Act", S. 157, a multi-faceted piece of legislation sponsored by Alaska Senator Lisa Murkowski, Denali's mountaineering contact station is now designated the Walter Harper Talkeetna Ranger Station, honoring the achievements of Athabaskan native who was the first to set foot on the summit of Denali on June 7, 1913. Harper, a 20-year-old guide, dog musher, trapper/hunter raised in the Koyukuk region of Alaska, was an instrumen-tal member of the first ascent team which also included Hudson Stuck, Harry Karstens, and Robert Tatum. Tragically, Harper died in 1918 along with his bride during a honeymoon voyage to Seattle; their steamer SS Princess Sophia struck a reef and sank off the coast of Juneau in dangerous seas, killing all 343 passengers and crew. A century after his history-making achievement, Harper is immortalized in Denali National Park by the Harper Glacier that bears his name, and now at the park building that all mountaineers must visit before embarking on their Denali expeditions. The ranger station's new sign was installed in December 2013, and a small celebration is planned for spring 2014 to recognize the new designation. Stay tuned ... - South District Ranger John Leonard 2013 Quick Facts Denali recorded its most individual summits (783) in any one season. The summit success rate of 68% is the highest percentage since 1977. • US residents accounted for 60% of climbers (693). -

2018 Net Proceeds by Permittee Report

Department of Revenue Tax Division/Charitable Gaming Net Proceeds for Period Ending 12/31/2018* Permit # Permittee Name Filing Period Net Proceeds 101116 A&A SCOTTISH RITE OF FREE MASONR, S. J. VALLEY OF 31-Dec-2018 24,733.88 1186 A.J. DIMOND HIGH SCHOOL ALUMNI FOUNDATION 31-Dec-2018 222,613.78 437 ABUSED WOMENS AID IN CRISIS INC 31-Dec-2018 70,256.86 2269 ACADEMY ADVISORY BOARD 31-Dec-2018 20,471.00 1539 ADVOCATES FOR VICTIMS OF VIOLENCE INC 31-Dec-2018 13,783.00 1394 AGDAAGUX TRIBAL COUNCIL 31-Dec-2018 67,355.02 3031 AIR FORCE SERGEANTS ASSOCIATION 31-Dec-2018 - 3009 AK ASSN FOR INFANT AND EARLY CHILDHOOD MENTAL HEAL 31-Dec-2018 - 105039 AK KRUSH INC 31-Dec-2018 - 84 AKEELA, INC 31-Dec-2018 39,768.00 968 AKIACHAK NATIVE COMMUNITY 31-Dec-2018 106,271.35 102098 AKIAK NATIVE COMMUNITY 31-Dec-2018 417,119.78 431 AL ASKA SHRINE TEMPLE 31-Dec-2018 37,025.03 626 ALANO CLUB OF FAIRBANKS 31-Dec-2018 95,197.56 1525 ALASKA 700 BOWLING CLUBS OF AMERICA 31-Dec-2018 47,519.93 654 ALASKA ADDICTION REHABILITATION SERVICES INC 31-Dec-2018 607.00 1343 ALASKA AIRMENS ASSOCIATION INC 31-Dec-2018 341,843.60 458 ALASKA ALL STAR HOCKEY ASSOCIATION 31-Dec-2018 20,167.00 2700 ALASKA AMATEUR SOFTBALL ASSOCIATION 31-Dec-2018 36,762.38 2184 ALASKA ARCTIC ICE JUNIOR HOCKEY TEAM 31-Dec-2018 69,899.12 974 ALASKA ASSOCIATION OF MUNICIPAL CLERKS 31-Dec-2018 6,970.00 2587 ALASKA ATTACHMENT AND BONDING ASSOCIATES 31-Dec-2018 37,058.62 1622 ALASKA AVIATION HERITAGE MUSEUM 31-Dec-2018 670.00 2631 ALASKA BASEBALL ACADEMY INC 31-Dec-2018 37,732.06 122001 ALASKA BASEBALL -

Services for Veterans in Alaska: Field Hearings in Anchorage and Fairbanks

S. HRG. 111–658 SERVICES FOR VETERANS IN ALASKA: FIELD HEARINGS IN ANCHORAGE AND FAIRBANKS HEARING BEFORE THE COMMITTEE ON VETERANS’ AFFAIRS UNITED STATES SENATE ONE HUNDRED ELEVENTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION FEBRUARY 16 AND 17, 2010 Printed for the use of the Committee on Veterans’ Affairs ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.access.gpo.gov/congress/senate U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 61–710 PDF WASHINGTON : 2010 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office, http://bookstore.gpo.gov. For more information, contact the GPO Customer Contact Center, U.S. Government Printing Office. Phone 202–512–1800, or 866–512–1800 (toll-free). E-mail, [email protected]. VerDate Nov 24 2008 20:49 Dec 09, 2010 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 H:\ACTIVE\021610AK.TXT SVETS PsN: PAULIN COMMITTEE ON VETERANS’ AFFAIRS DANIEL K. AKAKA, Hawaii, Chairman JOHN D. ROCKEFELLER IV, West Virginia RICHARD BURR, North Carolina, Ranking PATTY MURRAY, Washington Member BERNARD SANDERS, (I) Vermont LINDSEY O. GRAHAM, South Carolina SHERROD BROWN, Ohio JOHNNY ISAKSON, Georgia JIM WEBB, Virginia ROGER F. WICKER, Mississippi JON TESTER, Montana MIKE JOHANNS, Nebraska MARK BEGICH, Alaska SCOTT P. BROWN, Massachusetts1 ROLAND W. BURRIS, Illinois ARLEN SPECTER, Pennsylvania WILLIAM E. BREW, Staff Director LUPE WISSEL, Republican Staff Director 1 Hon. Scott P. Brown was recognized as a minority Member on March 24, 2010. (II) VerDate Nov 24 2008 20:49 Dec 09, 2010 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00002 Fmt 5904 Sfmt 5904 H:\ACTIVE\021610AK.TXT SVETS PsN: PAULIN CONTENTS FEBRUARY 16, 2010—ANCHORAGE SENATORS Page Begich, Hon. -

View Complete Timeline (PDF)

This illustrated timeline highlights events that have been important in the history of the Dena’ina. 12000 BP - AD 1000 Before the Underwater People 1778 - 1790S European Exploration 1779 - 1867 Russian America 1867 Sale of Alaska 1867 - 1884 Department of Alaska 1884 - 1912 District of Alaska 1912 - 1959 Territory of Alaska 1959 Statehood 1959 - PRESENT State of Alaska 1971 - PRESENT Land Claims 1975 - PRESENT Cultural Renewal DENA’INA TIME TRAVEL BEFORE WE MET THE “UNDERWATER PEOPLE” 12000 BP AD 500-1000 YOU ARE HERE 12000 BP. ICE AGE ENDS – PEOPLE ENTER COOK INLET BASIN As glaciers begin to recede from the upper Cook Inlet Basin, it becomes possible for human beings to live in the area for the first time. Little is known of the first inhabitants except that they used core and blade technology to hunt large land mammals. Matanuska Glacier. Photo copyright Mark Clime/Dreamstime.com 3 DENA’INA TIME TRAVEL BEFORE WE MET THE “UNDERWATER PEOPLE” 12000 BP AD 500 - 1000 YOU ARE HERE AD 500 – 1000. DENA’INA MOVE INTO SOUTHCENTRAL ALASKA The Dena’ina reach Cook Inlet in two area around Tyonek as well as Knik. Later, migrations. They first come through either the Dena’ina migrate south to Iliamna Rainy Pass or Ptarmigan Pass into the Susitna Lake, eventually crossing over to the River country, where they occupy the coastal Kenai Peninsula. Tuxedeni Bay pictographs. Courtesy of the Lake Clark National Park and Preserve. Photo by James W. Henderson 4 DENA’INA TIME TRAVEL BEFORE WE MET THE “UNDERWATER PEOPLE” 12000 BP AD 1000 YOU ARE HERE AD 1000. -

The National Congress of American Indians Resolution #SAC-12-062

N A T I O N A L C O N G R E S S O F A M E R I C A N I N D I A N S The National Congress of American Indians Resolution #SAC-12-062 TITLE: Commemorate the Centennial of the First Successful Climb of Denali in 1913, with Alaska Native Walter Harper First to Reach the Summit WHEREAS, we, the members of the National Congress of American Indians E XECUTIVE C OMMITTEE of the United States, invoking the divine blessing of the Creator upon our efforts and PRESIDENT purposes, in order to preserve for ourselves and our descendants the inherent sovereign Jefferson Keel Chickasaw Nation rights of our Indian nations, rights secured under Indian treaties and agreements with FIRST VICE-PRESIDENT the United States, and all other rights and benefits to which we are entitled under the Juana Majel Dixon Pauma Band of Mission Indians laws and Constitution of the United States, to enlighten the public toward a better RECORDING SECRETARY understanding of the Indian people, to preserve Indian cultural values, and otherwise Edward Thomas Central Council of Tlingit & Haida promote the health, safety and welfare of the Indian people, do hereby establish and Indian Tribes of Alaska submit the following resolution; and TREASURER W. Ron Allen Jamestown S’Klallam Tribe WHEREAS, the National Congress of American Indians (NCAI) was R EGIONAL V ICE- P RESIDENTS established in 1944 and is the oldest and largest national organization of American ALASKA Indian and Alaska Native tribal governments; and Bill Martin Central Council of Tlingit & Haida Indian Tribes of Alaska th WHEREAS, in the spring of 2013, on the 100 Anniversary of the first EASTERN OKLAHOMA S. -

Download Date 03/10/2021 22:40:53

When Uŋalaqłiq danced: stories of strength, suppression & hope Item Type Other Authors Qassataq, Ayyu Download date 03/10/2021 22:40:53 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/11122/11181 WHEN U^ALAQtlQ DANCED: STORIES OF STRENGTH, SUPPRESSION & HOPE By Ayyu Qassataq A Project Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Rural Development University of Alaska Fairbanks on the Traditional Lands of the Dena People of the Lower Tanana River May 2020 APPROVED: Dr. Khaih Zhuu Charlene B. Stern, Committee Chair Dr. Ch'andeelir Jessica C. Black, Committee Member Department of Alaska Native Studies and Rural Development, UAF Dr. Panigkaq Agatha John-Shields, Committee Member School of Education, UAA Patricia S. Sekaquaptewa, JD, Co-Chair Department of Alaska Native Studies & Rural Development (DANSRD) Abstract In the late 1800’s, the Evangelical Covenant Church established a mission in Ugalaqliq (Unalakleet), a predominantly Inupiaq community along the Norton Sound in Western Alaska. Missionaries were integral in establishing a localized education system under the direction of the General Agent of Education, Sheldon Jackson, in the early 1900’s. By 1915, the community was no longer engaging in ancestral practices such as deliberating, teaching and hosting ceremonies within the qargi. Nor were they uplifting shared history and relationships between villages or expressing gratitude for the bounty of the lands through traditional songs, dances, or celebrations such as theKivgiq Messenger Feast. In my research, I focus on events that occurred in Ugalaqliq around the turn of the 20th century and analyze how those events influenced the formation of the education system and its ongoing impacts on Native peoples and communities today. -

Yukon and Kuskokwim Whitefish Strategic Plan

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Whitefish Biology, Distribution, and Fisheries in the Yukon and Kuskokwim River Drainages in Alaska: a Synthesis of Available Information Alaska Fisheries Data Series Number 2012-4 Fairbanks Fish and Wildlife Field Office Fairbanks, Alaska May 2012 The Alaska Region Fisheries Program of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service conducts fisheries monitoring and population assessment studies throughout many areas of Alaska. Dedicated professional staff located in Anchorage, Fairbanks, and Kenai Fish and Wildlife Offices and the Anchorage Conservation Genetics Laboratory serve as the core of the Program’s fisheries management study efforts. Administrative and technical support is provided by staff in the Anchorage Regional Office. Our program works closely with the Alaska Department of Fish and Game and other partners to conserve and restore Alaska’s fish populations and aquatic habitats. Our fisheries studies occur throughout the 16 National Wildlife Refuges in Alaska as well as off- Refuges to address issues of interjurisdictional fisheries and aquatic habitat conservation. Additional information about the Fisheries Program and work conducted by our field offices can be obtained at: http://alaska.fws.gov/fisheries/index.htm The Alaska Region Fisheries Program reports its study findings through the Alaska Fisheries Data Series (AFDS) or in recognized peer-reviewed journals. The AFDS was established to provide timely dissemination of data to fishery managers and other technically oriented professionals, for inclusion in agency databases, and to archive detailed study designs and results for the benefit of future investigations. Publication in the AFDS does not preclude further reporting of study results through recognized peer-reviewed journals. -

Northwest Ordinance 1797- Above the Ohio River: OH, IN, IL, MI, WI

F304 Building America: The Pursuit of Land from 1607-1893 Class Notes 3 for: F304 Building America Northwest Territory- Northwest Ordinance 1797- Above the Ohio River: OH, IN, IL, MI, WI. Slavery was prohibited. It was considered to be one of the most important legislative acts of the Confederation Congress, it established the precedent by which the Federal government would be sovereign and expand westward with the admission of new states, rather than with the expansion of existing states and their established sovereignty under the Articles of Confederation. It was also precedent setting legislation with regard to American public domain lands. The U.S. Supreme Court recognized the authority of the Northwest Ordinance of 1789 within the applicable Northwest Territory as constitutional in Strader v. Graham, 51 U.S. 82, 96, 97 (1851), but did not extend the Ordinance to cover the respective states once they were admitted to the Union. The 1784 ordinance was criticized by George Washington in 1785 and James Monroe in 1786. Monroe convinced Congress to reconsider the proposed state boundaries; a review committee recommended repealing that part of the ordinance. Other politicians questioned the 1784 ordinance's plan for organizing governments in new states, and worried that the new states' relatively small sizes would undermine the original states' power in Congress. Other events such as the reluctance of states south of the Ohio River to cede their western claims resulted in a narrowed geographic focus. Territory: Kentucky- ceded from Virginia. Kentucky 1774-1810: Before 1775, the territory of Kentucky (and OH, IL, IN, MI, and WI) were all part of the colony of Virginia.