Tobias Garstecki

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Intial Estimation of the Numbers and Identification of Extant Non

Answers Research Journal 8 (2015):171–186. www.answersingenesis.org/arj/v8/lizard-kinds-order-squamata.pdf $Q,QLWLDO(VWLPDWLRQRIWKH1XPEHUVDQG,GHQWLÀFDWLRQRI Extant Non-Snake/Non-Amphisbaenian Lizard Kinds: Order Squamata Tom Hennigan, Truett-McConnell College, Cleveland, Georgia. $EVWUDFW %LRV\VWHPDWLFVLVLQJUHDWÁX[WRGD\EHFDXVHRIWKHSOHWKRUDRIJHQHWLFUHVHDUFKZKLFKFRQWLQXDOO\ UHGHÀQHVKRZZHSHUFHLYHUHODWLRQVKLSVEHWZHHQRUJDQLVPV'HVSLWHWKHODUJHDPRXQWRIGDWDEHLQJ SXEOLVKHGWKHFKDOOHQJHLVKDYLQJHQRXJKNQRZOHGJHDERXWJHQHWLFVWRGUDZFRQFOXVLRQVUHJDUGLQJ WKHELRORJLFDOKLVWRU\RIRUJDQLVPVDQGWKHLUWD[RQRP\&RQVHTXHQWO\WKHELRV\VWHPDWLFVIRUPRVWWD[D LVLQJUHDWIOX[DQGQRWZLWKRXWFRQWURYHUV\E\SUDFWLWLRQHUVLQWKHILHOG7KHUHIRUHWKLVSUHOLPLQDU\SDSHU LVmeant to produce a current summary of lizard systematics, as it is understood today. It is meant to lay a JURXQGZRUNIRUFUHDWLRQV\VWHPDWLFVZLWKWKHJRDORIHVWLPDWLQJWKHQXPEHURIEDUDPLQVEURXJKWRQ WKH $UN %DVHG RQ WKH DQDO\VHV RI FXUUHQW PROHFXODU GDWD WD[RQRP\ K\EULGL]DWLRQ FDSDELOLW\ DQG VWDWLVWLFDO EDUDPLQRORJ\ RI H[WDQW RUJDQLVPV D WHQWDWLYH HVWLPDWH RI H[WDQW QRQVQDNH QRQ DPSKLVEDHQLDQOL]DUGNLQGVZHUHWDNHQRQERDUGWKH$UN,WLVKRSHGWKDWWKLVSDSHUZLOOHQFRXUDJH IXWXUHUHVHDUFKLQWRFUHDWLRQLVWELRV\VWHPDWLFV Keywords: $UN(QFRXQWHUELRV\VWHPDWLFVWD[RQRP\UHSWLOHVVTXDPDWDNLQGEDUDPLQRORJ\OL]DUG ,QWURGXFWLRQ today may change tomorrow, depending on the data Creation research is guided by God’s Word, which and assumptions about that data. For example, LVIRXQGDWLRQDOWRWKHVFLHQWLÀFPRGHOVWKDWDUHEXLOW naturalists assume randomness and universal 7KHELEOLFDODQGVFLHQWLÀFFKDOOHQJHLVWRLQYHVWLJDWH -

Implementation of Article 16, Council Regulation (EC) No. 338/97, in the EU

Implementation of Article 16, Council Regulation (EC) No. 338/97, in the 25 Member States of the European Union Tobias Garstecki Report commissioned by the European Commission Contract 07.0402/2005/399949/MAR/E2 Report prepared by TRAFFIC Europe for the European Commission in completion of Contract 07.0402/2005/399949/MAR/E2 All material appearing in this publication is copyrighted and may be reproduced with permission. Any reproduction in full or in part of this publication must credit the European Commission as the copyright owner. The views of the authors expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect those of the European Commission or the TRAFFIC network, WWF or IUCN. The designation of geographical entities in this publication, and the presentation of the material, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the European Commission, TRAFFIC or its supporting organizations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The TRAFFIC symbol copyright and Registered Trademark ownership is held by WWF. TRAFFIC is a joint programme of WWF and IUCN. Suggested citation: Garstecki, T (2006): Implementation of Article 16, Council Regulation (EC) No. 338/97, in the 25 Member States of the European Union. A TRAFFIC Europe Report for the European Commission, Brussels, Belgium. Implementation of Article 16, EC Regulation 338/97, in the 25 Member States of the European Union CONTENTS Acknowledgements 1 Executive Summary 2 Background and project description 3 Objectives 4 Comparison of penalties for wildlife trade regulation offences in EU Member States 4 Table 1: Comparison of minimum and maximum penalties and seizure/confiscation powers in relation to Article 16 of EC Regulation 338/97 in EU Member States 9 Procedures for determining penalties and monetary compensation 16 Overview 16 1. -

Captive Wildlife Regulations, 2021, W-13.12 Reg 5

1 CAPTIVE WILDLIFE, 2021 W-13.12 REG 5 The Captive Wildlife Regulations, 2021 being Chapter W-13.12 Reg 5 (effective June 1, 2021). NOTE: This consolidation is not official. Amendments have been incorporated for convenience of reference and the original statutes and regulations should be consulted for all purposes of interpretation and application of the law. In order to preserve the integrity of the original statutes and regulations, errors that may have appeared are reproduced in this consolidation. 2 W-13.12 REG 5 CAPTIVE WILDLIFE, 2021 Table of Contents PART 1 PART 5 Preliminary Matters Zoo Licences and Travelling Zoo Licences 1 Title 38 Definition for Part 2 Definitions and interpretation 39 CAZA standards 3 Application 40 Requirements – zoo licence or travelling zoo licence PART 2 41 Breeding and release Designations, Prohibitions and Licences PART 6 4 Captive wildlife – designations Wildlife Rehabilitation Licences 5 Prohibition – holding unlisted species in captivity 42 Definitions for Part 6 Prohibition – holding restricted species in captivity 43 Standards for wildlife rehabilitation 7 Captive wildlife licences 44 No property acquired in wildlife held for 8 Licence not required rehabilitation 9 Application for captive wildlife licence 45 Requirements – wildlife rehabilitation licence 10 Renewal 46 Restrictions – wildlife not to be rehabilitated 11 Issuance or renewal of licence on terms and conditions 47 Wildlife rehabilitation practices 12 Licence or renewal term PART 7 Scientific Research Licences 13 Amendment, suspension, -

Captive Wildlife Allowed List

Saskatchewan Captive Wildlife Allowed Species List (as of June 1, 2021) AMPHIBIANS (CLASS AMPHIBIA) Class (Common Name) Scientific Name Family Ambystomatidae Axolotl Ambystoma mexicanum Marble Salamander Ambystoma opacum Family Bombinatoridae Oriental Fire-Bellied Toad Bombina orientalis Family Bufonidae Green Toad Anaxyrus debilis Black Indonesian Toad Bufo asper Indonesian Toad Duttaphrynus melanostictus Family Ceratophryidae Surinam Horned Frog Ceratophrys cornuta Chacoan Horned Frog Ceratophrys cranwelli Argentine Horned Frog Ceratophrys ornata Budgett’s Frog Lepidobatrachus laevis Family Dendrobatidae Dart Poison Frog Dendrobates auratus Yellow-banded Poison Dart Frog Dendrobates leucomelas Dyeing Dart Frog Dendrobates tinctorius Yellow-striped Poison Frog Dendrobates truncatus Family Hylidae Clown Tree Frog Dendropsophus leucophyllatus Bird Poop Tree Frog Dendropsophus marmoratus Barking Tree Frog Dryophytes gratiosus Squirrel Tree Frog Dryophytes squirellus Green Tree Frog Dryophytes cinereus Cuban Tree Frog Osteopilus septentrionalis Haitian Giant Tree Frog Osteopilus vastus White’s Tree Frog Ranoidea caerulea Brazilian Black and White Milky Frog Trachycephalus resinifictrix Hyperoliidae African Reed Frog Hyperolius concolor Family Mantellidae Baron’s Mantella Mantella baroni Brown Mantella Mantella betsileo Family Megophryidae Long-nosed Horned Frog Megophrys nasuta Family Microhylidae Tomato Frog Dyscophus guineti Chubby Frog Kaloula pulchra Banded Rubber Frog Phrynomantis bifasciatus Emerald Hopper Frog Scaphiophryne madagascariensis -

ZOO REPORT PROFI the Content

No. 1 / march 2013 special supplement ZOO REPORT PROFI The Content The Speech Vladimir V. Spitsin Zooreport the magazine for friends of the Brno Zoo march 2013; No. 1/13, volume XV PAGE 3 The Largest Chameleon Michal Balcar Editor: Zoologická zahrada města Brna U Zoo 46, 635 00 Brno, Czech Republic tel.: +420 546 432 311 fax: +420 546 210 000 PAGE 4 e-mail: [email protected] Slavkovský Forest Protected Landscape Park RNDr. Pavel Řepa Publisher: Peleos, spol. s r.o. e-mail: [email protected] PAGE 5 Editor’s office address: Brno’s New Komodo Dragon Zoologická zahrada města Brna Michal Balcar Redakce Zooreport U Zoo 46, 635 00 Brno, Czech Republic tel.: +420 546 432 370 fax: +420 546 210 000 e-mail: [email protected] PAGES 6, 7 The City of Brno Has Assigned Hlídka to Zoo Editor manager: Eduard Stuchlík Bc. Eduard Stuchlík Specialist readers: PAGE 8 RNDr. Bohumil Král, CSc. Hot News Mgr. Lubomír Selinger (red) Emendation: Rosalind Miranda PAGE 9 Distribution: Kamchatka Brown Bears Love Honey and Snow 500 pcs in the English version Eduard Stuchlík 1,500 pcs in the Czech version Photos by: PAGE 10 Eduard Stuchlík Polar Bear Cora First page: is Taking Care of her Second Set of Twin Polar bears Eduard Stuchlík UNSALEABLE PAGE 11 2 The Speech EARAZA Organises Nine International Animal Protection Programmes The 19th annual conference of the Eurasian Regional Association of Zoos and Aquariums (EARAZA) will take place at the end of May 2013 at Brno Zoo. I would there- fore like to familiarize ZooReport readers with the association of which I have been the head since its foundation in 1994. -

JNCC Report No. 378 Checklist of Herpetofauna Listed in the CITES Appendices and in EC Regulation No

JNCC Report No. 378 Checklist of herpetofauna listed in the CITES appendices and in EC Regulation No. 338/97 10th Edition 2005 compiled by UNEP-WCMC © JNCC 2005 The JNCC is the forum through which the three country conservation agencies - the Countryside Council for Wales, English Nature and Scottish Natural Heritage - deliver their statutory responsibilities for Great Britain as a whole, and internationally. These responsibilities contribute to sustaining and enriching biological diversity, enhancing geological features and sustaining natural systems. As well as a source of advice and knowledge for the public, JNCC is the Government's wildlife adviser, providing guidance on the development of policies for, or affecting, nature conservation in Great Britain or internationally. Published by: Joint Nature Conservation Committee Copyright: 2005 Joint Nature Conservation Committee ISBN: 1st edition published 1979 ISBN 0-86139-075-X 2nd edition published 1981 ISBN 0-86139-095-4 3rd edition published 1983 ISBN 0-86139-224-8 4th edition published 1988 ISBN 0-86139-465-8 5th edition published 1993 ISBN 1-873701-46-2 6th edition published 1995 ISSN 0963-8091 7th edition published 1999 ISSN 0963-8091 8th edition published 2001 ISSN 0963-8091 9th edition published 2003 ISSN 0963-8091 10th edition published 2005 ISSN 0963-8091 Citation: UNEP-WCMC (2005). Checklist of herpetofauna listed in the CITES appendices and in EC Regulation 338/97. 10th edition. JNCC Report No. 378. Further copies of this report are available from: CITES Unit Joint Nature Conservation Committee Monkstone House City Road Peterborough PE1 1JY United Kingdom Tel: +44 1733 562626 Fax: +44 1733 555948 This document can also be downloaded from: http://www.ukcites.gov.uk and www.jncc.gov.uk Prepared under contract from the Joint Nature Conservation Committee by UNEP- WCMC. -

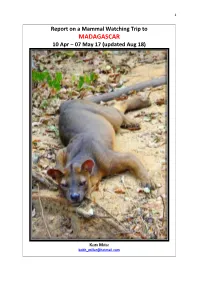

MADAGASCAR 10 Apr – 07 May 17 (Updated Aug 18)

1 Report on a Mammal Watching Trip to MADAGASCAR 10 Apr – 07 May 17 (updated Aug 18) Keith Millar [email protected] 2 Contents Itinerary and References (p3-p5) Conservation Issues (p6) Site by Site Guide: Berenty Private Reserve (p7-p10) Ranomafana National Park (p11-p15) Ankazomivady Forest (p15) Masoala National Park (p16-p18) Nosy Mangabe Special Reserve (pg 18) Kirindy Forest (pg19-p22) Ifaty-Mangily (pg23-p24) Andasibe/ Mantadia National Park (p25-p26) Palmarium Private Reserve (Ankanin’ny Nofy) (p27-p28) Montagne d’Ambre NP (p29-p30) Ankarana NP (P31-P32) Loboke Integrated Reserve (pg33-34) Checklists (pg35-p40) Grandidier’s Baobabs (Adansonia grandidieri) 3 In April 2017 I travelled with a friend, Stephen Swan, to Madagascar and spent 29 days focused on trying to locate as many mammal species as possible, together with the endemic birds and reptiles. At over 1,000 miles long and 350 miles wide, the world’s fourth largest island can be a challenge to get around, and transport by road is not always the practical option. So we also took several internal flights with Madagascar Airlines. In our experience, a reliable carrier, but when ‘technical difficulties’ did maroon us for some 24 hours, a pre-planned ‘extra’ day in the programme at least meant that we were able to stay ‘on target’ in terms of the sites and animals we wished to see. We flew Kenya Airlines to Antananarivo (Tana) via Nairobi (flights booked through Trailfinders https://www.trailfinders.com/ ) I chose Cactus Tours https://www.cactus-madagascar.com/ as our ground agent. -

Madagascar, Mauritius & Reunion 2016

Field Guides Tour Report Madagascar, Mauritius & Reunion 2016 Nov 5, 2016 to Dec 1, 2016 Phil Gregory & local guide For our tour description, itinerary, past triplists, dates, fees, and more, please VISIT OUR TOUR PAGE. This juvenile Ring-tailed Lemur was absolutely adorable and possibly the inspiration for Yoda. Photo by participant Sheila Vince. This was my seventh Field Guides Madagascar tour, and ninth overall. This time round, with mercifully few Madagascar Air flights, we enjoyed close to an ideal itinerary. Very dry conditions certainly depressed some small bird activity, and both chameleons and snakes were remarkably scarce. It was a vintage trip for lemurs however, with a very good range of species and great views of some very special ones, like sifakas, Indri, mouse-lemurs, bamboo-lemurs, and woolly lemurs. We began by driving up to Ankarafantsika, meeting up with our excellent local guide and his wife, and staying at the park. A Torotoroka Scops-Owl roosting under a hut roof right by the park entrance was a bonus, and both White-headed and Sickle-billed vangas showed, as did the first of many wonderful lemurs, in this case Coquerel's Sifaka. A short night walk got us Golden-brown Mouse-Lemur and Oustalet's Chameleon, and a brief view of Western Tuft-tailed Rat. The following day, we had a mission to see all of the special species. We began very well with a newly discovered nest of Schlegel's Asity, soon followed by White-breasted Mesite and eventually (after breakfast) a splendid Van Dam's Vanga -- a rare species that is easily missed. -

Wrasses 24 Dipl.- Biol

No!"#$ !"#$The magazine for aquarists and terrarists%% ! A jewel from the Congo AQUARISTIC TERRARISTIC A live- bearing waterlily Leopard Tortoise "##$!%& 02_C.indd 1 10.02.2012 12:09:21 2 NEWS 102 Content Impressum Little giants from Zambia 4 Preview: A jewel from the Congo 8 Herausgeber: Wolfgang Glaser News No 103 Chefredakteur: Dipl. -Biol. Frank Schäfer Tyttocharax cochui 12 will appear in autumn 2012 Redaktionsbeirat: Thorsten Holtmann Don´t miss it! Volker Ennenbach A Goldfish... 16 Dr. med. vet. Markus Biffar A livebearing waterlily 20 Thorsten Reuter Manuela Sauer Very different sexes – wrasses 24 Dipl.- Biol. Klaus Diehl Chinese Highfin Banded Shark 28 Layout: Bärbel Waldeyer Übersetzungen: Mary Bailey Rarities from the Congo 32 Gestaltung: Aqualog Animalbook GmbH The Malagasy Giant Chameleon 36 Frederik Templin Titelgestaltung: Petra Appel, Steffen Kabisch Live food in bags 40 Druck: Bechtle Druck&Service, Esslingen Colorful creepers for the terrarium44 Gedruckt am: 15.2.2012 Anzeigendisposition: Aqualog Animalbook GmbH und Verlag Liebigstraße 1, D-63110 Rodgau Tel: 49 (0) 61 06 - 697977 Wollen Sie keine Ausgabe der News versäumen ? Fax: 49 (0) 61 06 - 697983 Werden Sie Abonnent(in) und füllen Sie einfach den Abonnenten-Abschnitt aus e-mail: [email protected] und schicken ihn an: Aqualog Animalbook GmbH, Liebigstr.1, D- 63110 Rodgau http://www.aqualog.de Hiermit abonniere ich die Ausgaben 102-105 (2012) zum Preis von g12 ,- für 4 Ausgaben, All rights reserved.The publishers do not accept liability for (außerhalb Deutschlands g 19,90) inkl. Porto und Verpackung. unsolicited manuscripts or photographs. Articles written by named authors do not necessarily represent the editors’ opinion. -

Female Heterogamety in Madagascar Chameleons

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Female heterogamety in Madagascar chameleons (Squamata: Chamaeleonidae: Received: 04 March 2015 Accepted: 14 July 2015 Furcifer): differentiation of sex and Published: 19 August 2015 neo-sex chromosomes Michail Rovatsos1, Martina Johnson Pokorná1,2, Marie Altmanová1 & Lukáš Kratochvíl1 Amniotes possess variability in sex determining mechanisms, however, this diversity is still only partially known throughout the clade and sex determining systems still remain unknown even in such a popular and distinctive lineage as chameleons (Squamata: Acrodonta: Chamaeleonidae). Here, we present evidence for female heterogamety in this group. The Malagasy giant chameleon (Furcifer oustaleti) (chromosome number 2n = 22) possesses heteromorphic Z and W sex chromosomes with heterochromatic W. The panther chameleon (Furcifer pardalis) (2n = 22 in males, 21 in females), the second most popular chameleon species in the world pet trade, exhibits a rather rare Z1Z1Z2Z2/Z1Z2W system of multiple sex chromosomes, which most likely evolved from W-autosome fusion. Notably, its neo-W chromosome is partially heterochromatic and its female-specific genetic content has expanded into the previously autosomal region. Showing clear evidence for genotypic sex determination in the panther chameleon, we resolve the long-standing question of whether or not environmental sex determination exists in this species. Together with recent findings in other reptile lineages, our work demonstrates that female heterogamety is widespread among amniotes, adding another important piece to the mosaic of knowledge on sex determination in amniotes needed to understand the evolution of this important trait. Chameleons (family Chamaeleonidae) are well-known, highly distinctive lizards characterised by their unique morphological and physiological traits, such as independently movable stereoscopic eyes, pro- jectable, ballistic tongue, prehensile feet, and the notable ability in many species to change the colour of their skin. -

A Phylogeographic Assessment of the Malagasy Giant Chameleons (Furcifer Verrucosus and Furcifer Oustaleti)

RESEARCH ARTICLE A Phylogeographic Assessment of the Malagasy Giant Chameleons (Furcifer verrucosus and Furcifer oustaleti) Antonia M. Florio*, Christopher J. Raxworthy Department of Herpetology, American Museum of Natural History, New York, NY, United States of America * [email protected] a11111 Abstract The Malagasy giant chameleons (Furcifer oustaleti and Furcifer verrucosus) are sister spe- cies that are both broadly distributed in Madagascar, and also endemic to the island. These species are also morphologically similar and, because of this, have been frequently mis- identified in the field. Previous studies have suggested that cryptic species are nested within OPEN ACCESS this chameleon group, and two subspecies have been described in F. verrucosus.Inthis Citation: Florio AM, Raxworthy CJ (2016) A study, we utilized a phylogeographic approach to assess genetic diversification within these Phylogeographic Assessment of the Malagasy Giant chameleons. This was accomplished by (1) identifying clades within each species sup- Chameleons (Furcifer verrucosus and Furcifer oustaleti). PLoS ONE 11(6): e0154144. doi:10.1371/ ported by both mitochondrial and nuclear DNA, (2) assessing divergence times between journal.pone.0154144 clades, and (3) testing for niche divergence or conservatism. We found that both F. oustaleti Editor: Aristeidis Parmakelis, National & Kapodistrian and F. verrucosus could be readily identified based on genetic data, and within each spe- University of Athens, Faculty of Biology, GREECE cies, there are two well-supported clades. However, divergence times are not contemporary Received: June 16, 2015 and spatial patterns are not congruent. Diversification within F. verrucosus occurred during the Plio-Pleistocene, and there is evidence for niche divergence between a southwestern Accepted: April 8, 2016 and southeastern clade, in a region of Madagascar that shows no obvious landscape barri- Published: June 3, 2016 ers to dispersal. -

Gazette Part II, June 4, 2021

THE SASKATCHEWAN GAZETTE, 4 juin 2021 361 The Saskatchewan Gazette PUBLISHED WEEKLY BY AUTHORITY OF THE QUEEN’S PRINTER/PUBLIÉE CHAQUE SEMAINE SOUS L’AUTORITÉ DE L’IMPRIMEUR DE LA REINE PART II/PARTIE II Volume 117 REGINA, FRIDAY, JUNE 4, 2021/REGINA, vendredi 04 juin 2021 No. 22/nº 22 PART II/PARTIE II REVISED REGULATIONS OF SASKATCHEWAN/ RÈGLEMENTS RÉVISÉS DE LA SASKATCHEWAN TABLE OF CONTENTS/TABLE DES MATIÈRES W‑13.12 Reg 5 The Captive Wildlife Regulations, 2021 ...................................... 363 SR 68/2021 The 2018 Farm and Ranch Water Infrastructure Program Amendment Regulations, 2021 ................................. 418 SR 69/2021 The Special‑care Homes Rates Amendment Regulations, 2021 ...................................................................... 419 SR 70/2021 The Wildlife Amendment Regulations, 2021 ............................... 420 SR 71/2021 The Active Families Benefit Regulations, 2021 ........................... 423 Revised Regulations of Saskatchewan 2021/ 362 RèglementsTHE SASKATCHEWAN Révisés de GAZETTE, la Saskatchewan JUNE 4, 2021 2021 April 9, 2021 The Employment Program Regulations, 2021 .................................................................................................................. E‑13.1 Reg 15 The Municipal Employees’ Pension (Contribution Rates) Amendment Regulations, 2021 ............................................ SR 34/2021 The Sask911 Fees Amendment Regulations, 2021 ..........................................................................................................