Indian Mythology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

@Ibet,@Binu^ Un! Lupun

@be @olbeddeg of jUnlis, @ibet,@binu^ un! luPun by Lawrcnce Durdin-hobertron Cesata Publications, Eire Copyrighted Material. All Rights Reserved. The cover design. by Anna Durdin-Robertson. is a mandala oi a Chinese rlraqon goddess. Lawrence Durdln Rot,erlson. li_6 r2.00 Copyrighted Material. All Rights Reserved. The Goddesses of India, Tibet, China and Japan Copyrighted Material. All Rights Reserved. The Goddesses of India, Tibet, China and Japan by Lawrence Durdin-Robertron, M.A. (Dublin) with illustrations by Arna Durdin-Robertson Cesara Publications Huntington Castle, Clonegal, Enniscorthy. Eire. Printed by The Nationalist, Carlow. Eire. Anno Deae Cesara. Hiberniae Dominae. MMMMCCCXXIV Copyrighted Material. All Rights Reserved. Thir serle. of books is written in bonour of The lrish Great Mother, Cessrs aod The Four Guardian Goddesses of lreland, Dsna, Banba' Fodhla and Eire. It is dedicated to my wife, Pantela. Copyrighted Material. All Rights Reserved. CONTENTS I. The Goddesses of India'...'...'........"..'..........'....'..... I II. The Goddesses of Tlbet ............. ................."..,',,., 222 lll. Thc Goddesses of China ...............'..'..'........'...'..' 270 lV. The Goddesscs of Japan .........'.............'....'....'.. " 36 I List of abbreviations ....'........'...."..'...467 Bibfiogr.phy and Acknowledgments....'........'....'...,,,,.,'.,, 469 Index ................ .,...,.........,........,,. 473 Copyrighted Material. All Rights Reserved. Copyrighted Material. All Rights Reserved. Copyrighted Material. All Rights Reserved. SECTION ONE The Goddesses of India and Tibet NAMES: THE AMMAS, THE MOTHERS. ETYMoLoGY: [The etymology of the Sanskrit names is based mainly on Macdonell's Sanskrit Dictionary. The accents denot- ing the letters a, i and 0 are used in the Egrmology sections; elsewhere they are used only when they are necessary for identification.] Indian, amma, mother: cf. Skr. amba, mother: Phrygian Amma, N. -

Mahabharata Tatparnirnaya

Mahabharatha Tatparya Nirnaya Chapter XIX The episodes of Lakshagriha, Bhimasena's marriage with Hidimba, Killing Bakasura, Draupadi svayamwara, Pandavas settling down in Indraprastha are described in this chapter. The details of these episodes are well-known. Therefore the special points of religious and moral conduct highlights in Tatparya Nirnaya and its commentaries will be briefly stated here. Kanika's wrong advice to Duryodhana This chapter starts with instructions of Kanika an expert in the evil policies of politics to Duryodhana. This Kanika was also known as Kalinga. Probably he hailed from Kalinga region. He was a person if Bharadvaja gotra and an adviser to Shatrujna the king of Sauvira. He told Duryodhana that when the close relatives like brothers, parents, teachers, and friends are our enemies, we should talk sweet outwardly and plan for destroying them. Heretics, robbers, theives and poor persons should be employed to kill them by poison. Outwardly we should pretend to be religiously.Rituals, sacrifices etc should be performed. Taking people into confidence by these means we should hit our enemy when the time is ripe. In this way Kanika secretly advised Duryodhana to plan against Pandavas. Duryodhana approached his father Dhritarashtra and appealed to him to send out Pandavas to some other place. Initially Dhritarashtra said Pandavas are also my sons, they are well behaved, brave, they will add to the wealth and the reputation of our kingdom, and therefore, it is not proper to send them out. However, Duryodhana insisted that they should be sent out. He said he has mastered one hundred and thirty powerful hymns that will protect him from the enemies. -

Srimad-Bhagavatam – Canto Five” by His Divine Grace A.C

“Srimad-Bhagavatam – Canto Five” by His Divine Grace A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada. Summary: Srimad-Bhagavatam is compared to the ripened fruit of Vedic knowledge. Also known as the Bhagavata Purana, this multi-volume work elaborates on the pastimes of Lord Krishna and His devotees, and includes detailed descriptions of, among other phenomena, the process of creation and annihilation of the universe. His Divine Grace A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada considered the translation of the Bhagavatam his life’s work. COPYRIGHT NOTICE: This is an evaluation copy of the printed version of this book, and is NOT FOR RESALE. This evaluation copy is intended for personal non-commercial use only, under the “fair use” guidelines established by international copyright laws. You may use this electronic file to evaluate the printed version of this book, for your own private use, or for short excerpts used in academic works, research, student papers, presentations, and the like. You can distribute this evaluation copy to others over the Internet, so long as you keep this copyright information intact. You may not reproduce more than ten percent (10%) of this book in any media without the express written permission from the copyright holders. Reference any excerpts in the following way: “Excerpted from “Srimad-Bhagavatam” by A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada, courtesy of the Bhaktivedanta Book Trust International, www.Krishna.com.” This book and electronic file is Copyright 1975-2003 Bhaktivedanta Book Trust International, 3764 Watseka Avenue, Los Angeles, CA 90034, USA. All rights reserved. For any questions, comments, correspondence, or to evaluate dozens of other books in this collection, visit the website of the publishers, www.Krishna.com. -

Module 1A: Uttar Pradesh History

Module 1a: Uttar Pradesh History Uttar Pradesh State Information India.. The Gangetic Plain occupies three quarters of the state. The entire Capital : Lucknow state, except for the northern region, has a tropical monsoon climate. In the Districts :70 plains, January temperatures range from 12.5°C-17.5°C and May records Languages: Hindi, Urdu, English 27.5°-32.5°C, with a maximum of 45°C. Rainfall varies from 1,000-2,000 mm in Introduction to Uttar Pradesh the east to 600-1,000 mm in the west. Uttar Pradesh has multicultural, multiracial, fabulous wealth of nature- Brief History of Uttar Pradesh hills, valleys, rivers, forests, and vast plains. Viewed as the largest tourist The epics of Hinduism, the Ramayana destination in India, Uttar Pradesh and the Mahabharata, were written in boasts of 35 million domestic tourists. Uttar Pradesh. Uttar Pradesh also had More than half of the foreign tourists, the glory of being home to Lord Buddha. who visit India every year, make it a It has now been established that point to visit this state of Taj and Ganga. Gautama Buddha spent most of his life Agra itself receives around one million in eastern Uttar Pradesh, wandering foreign tourists a year coupled with from place to place preaching his around twenty million domestic tourists. sermons. The empire of Chandra Gupta Uttar Pradesh is studded with places of Maurya extended nearly over the whole tourist attractions across a wide of Uttar Pradesh. Edicts of this period spectrum of interest to people of diverse have been found at Allahabad and interests. -

Uttarakandam

THE RAMAYANA. Translated into English Prose from the original Sanskrit of Valmiki. UTTARAKANDAM. M ra Oer ii > m EDITED AND PUBLISHED Vt MANMATHA NATH DUTT, MA. CALCUTTA. 1894. Digitized by VjOOQIC Sri Patmanabha Dasa Vynchi Bala Sir Rama Varma kulasekhara klritapatl manney sultan maha- RAJA Raja Ramraja Bahabur Shamshir Jung Knight Grand Commander of most Emi- nent order of the Star of India. 7gK afjaraja of ^xavancoxe. THIS WORK IS RESPECTFULLY INSCRIBED BY MANMATHA NATH DUTT. In testimony of his veneration for His Highness and in grateful acknowledgement of the distinction conferred upon him while in His Highness* capital, and the great pecuniary help rendered by his Highness in publishing this work. Digitized by VjOOQ IC T — ^ 3oVkAotC UTTARA KlAlND^M, SECTION I. \Jn the Rakshasas having been slain, all the ascetics, for the purpose of congratulating Raghava, came to Rama as he gained (back) his kingdom. Kau^ika, and Yavakrita, and Gargya, and Galava, and Kanva—son unto Madhatithi, . who dwelt in the east, (came thither) ; aikl the reverend Swastyastreya, and Namuchi,and Pramuchi, and Agastya, and the worshipful Atri, aud Sumukha, and Vimukha,—who dwelt in the south,—came in company with Agastya.* And Nrishadgu, and Kahashi, and Dhaumya, and that mighty sage —Kau^eya—who abode in the western "quarter, came there accompanied by their disciples. And Vasishtha and Ka^yapa and Atri and Vicwamitra with Gautama and Jamadagni and Bharadwaja and also the seven sages,t who . (or aye resided in the northern quarter, (came there). And on arriving at the residence of Raghava, those high-souled ones, resembling the fire in radiance, stopped at the gate, with the intention of communicating their arrival (to Rama) through the warder. -

Srimad-Bhagavatam – Canto Ten” by His Divine Grace A.C

“Srimad-Bhagavatam – Canto Ten” by His Divine Grace A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada. Summary: Srimad-Bhagavatam is compared to the ripened fruit of Vedic knowledge. Also known as the Bhagavata Purana, this multi-volume work elaborates on the pastimes of Lord Krishna and His devotees, and includes detailed descriptions of, among other phenomena, the process of creation and annihilation of the universe. His Divine Grace A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada considered the translation of the Bhagavatam his life’s work. COPYRIGHT NOTICE: This is an evaluation copy of the printed version of this book, and is NOT FOR RESALE. This evaluation copy is intended for personal non- commercial use only, under the “fair use” guidelines established by international copyright laws. You may use this electronic file to evaluate the printed version of this book, for your own private use, or for short excerpts used in academic works, research, student papers, presentations, and the like. You can distribute this evaluation copy to others over the Internet, so long as you keep this copyright information intact. You may not reproduce more than ten percent (10%) of this book in any media without the express written permission from the copyright holders. Reference any excerpts in the following way: “Excerpted from “Srimad-Bhagavatam” by A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada, courtesy of the Bhaktivedanta Book Trust International, www.Krishna.com.” This book and electronic file is Copyright 1977-2003 Bhaktivedanta Book Trust International, 3764 Watseka Avenue, Los Angeles, CA 90034, USA. All rights reserved. For any questions, comments, correspondence, or to evaluate dozens of other books in this collection, visit the website of the publishers, www.Krishna.com. -

Krmi Ii Krmi Ii. Krodha I. Krodha

KRMI II 418 KRPA II the ly sons Nrga, Nara, Krmi, Suvrata and Sibi. (Agni ran to Kubera to inform him of this theft. It is stated Purana, Chapter 227). in Mahabharata, Vana Parva, Chapter 285, Stanza 2 II. wife KRMI A of Usinara. (See under Krmi I). that these Krodhavasas were present in the army of KRMI III. A Ksatriya dynasty. (Udyoga Parva, Ravana. Chapter 74, Verse J3). KROSANA. A female attendant of Skanda. (M.B. Salya KRMI IV. river. A (Bhlsma Parva, Chapter 9, Verse 17). Parva, Chapter 46, Stanza 1 7) KRMIBHOJANA (M). One of the twentyeight hells. KROSTA. A son of Yadu. Sahasrada, Payoda, Krosta, (See Naraka under Kala I) . Nila and Ajika were the five sons of Yadu. (Harivamsa, KRMILA. A king born in the Puru dynasty. There was Chapter 38). a king in the dynasty called Bahyasva, who had five KRPA I. A King in ancient India. He never ate flesh. sons called Srnjaya, Brhadisu, Mukula, Krmila and (Anusasana Parva, Chapter 115, Verse 64). Yavmara. In later years became famous as Pan- they KRPA II. (KRPACARYA) . calas. (Agni Purana, : Chapter 278) 1). Genealogy. Descended from Visnu thus Brahma- KRMlSA. A hell known as also. Krmibhojana (See Atri Candra Budha Pururavas Ayus Nahusa under Kala I.) Yayati Puru Janamejaya Pracinvan Pravlra KRODHA I. A famous Asura born to his Kasyapa by Namasyu Vitabhaya Sundu Bahuvidha Sariiyati wife Kala. (M.B. Adi Parva, Chapter 65, Stanza 35). Rahovadi Raudrasva Matinara Santurodha KRODHA II. It is stated in thatKrodha was Bhagavata Dusyanta Bharata Suhota Gala Garda Suketu born from the of Brahma. -

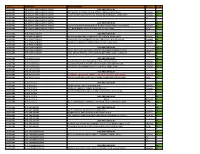

Location PLATETITLE SIXTYCHARNAME Source Count GHABHARA MULNAYAK SHRI MAHÄVIR SWÄMI 1993 PRATISHTHA by GHABHARA MULNAYAK SHRI MAHÄVIR SWÄMI DRS

Location PLATETITLE SIXTYCHARNAME Source Count GHABHARA MULNAYAK SHRI MAHÄVIR SWÄMI 1993 PRATISHTHA BY GHABHARA MULNAYAK SHRI MAHÄVIR SWÄMI DRS. DEEPAK & HIMANI DALIA & ANOKHI, NIRALI & ANERI DALIA Previous 57 GHABHARA MULNAYAK SHRI MAHÄVIR SWÄMI SATISH-KINNARY,AAKASH-PURVA-RIYAAN-NAIYOMI,BADAL-SONIA SHAH Previous 59 GHABHARA MULNAYAK SHRI MAHÄVIR SWÄMI NA 0 GHABHARA MULNAYAK SHRI MAHÄVIR SWÄMI 0 GHABHARA MULNAYAK SHRI MAHÄVIR SWÄMI 2009 PRATISHTHA BY 18 GHABHARA MULNAYAK SHRI MAHÄVIR SWÄMI VAIDYA RAMANBEN BHAKKAMBHAI TUSHAR DIMPLE HEMLATA PRABODH Gheeboli 57 GHABHARA MULNAYAK SHRI MAHÄVIR SWÄMI DR. CHANDRAKANT PRANLAL SHAH AND DEVYANI SHAH Raffle 46 0 GHABHARA SHRI PÄRSHVANÄTH 1993 PRATISHTHA BY 18 GHABHARA SHRI PÄRSHVANÄTH DR.RASHMI DIPCHAND, CHANDRIKA, RAJU, MONA, HITEN GARDI Previous 54 GHABHARA SHRI PÄRSHVANÄTH KERNEL,CHETNA,RAJA,MEENA,ASHISH,AMI,SHAILEE & SUJAL PARIKH Previous 58 GHABHARA SHRI PÄRSHVANÄTH NAGINDAS-VIJKORBEN, ARVIND-KIRAN, MANISH, ALKA SHAH Previous 51 GHABHARA SHRI PÄRSHVANÄTH 0 GHABHARA SHRI PÄRSHVANÄTH 2009 PRATISHTHA BY 18 GHABHARA SHRI PÄRSHVANÄTH ANISH, ANJALI, DULARI PARAG, MEMORY OF SHARDA MAFATLAL DOSHI Gheeboli 60 GHABHARA SHRI PÄRSHVANÄTH JYOTI PRADIP GRISHMA JUGNU SANYA PINKY MEHUL SAHIL & ARMAAN Raffle 60 0 GHABHARA SHRI SHÄNTINÄTH 1993 PRATISHTHA BY 18 GHABHARA SHRI SHÄNTINÄTH SURESH-PUSHPA, SNEHAL-RUPA & PARAG-TORAL BHANSALI Previous 49 GHABHARA SHRI SHÄNTINÄTH KUSUM & DALPATLAL PARIKH FAMILY BY REKHA AND BIPIN PARIKH Previous 57 GHABHARA SHRI SHÄNTINÄTH JAYANTILAL, NITIN-MEENA, MICHELLE, JESSICA, JAMIE SHAH Previous 54 GHABHARA SHRI SHÄNTINÄTH 0 GHABHARA SHRI SHÄNTINÄTH 2009 PRATISHTHA BY 18 GHABHARA SHRI SHÄNTINÄTH IN PARENTS MEMORY BY PARESH,LOPA,JATIN AND AMIT SHAH FAMILY Gheeboli 59 GHABHARA SHRI SHÄNTINÄTH SUSHILA-NAVIN SHAH AND FAMILY JAINIE JINESH PREM KOMAL KAJOL Raffle 60 0 GHABHARA SHRI AJITNÄTH 1993 PRATISHTHA BY 18 GHABHARA SHRI AJITNÄTH DR.ANIL-BHARTI, RITESH & REEPAL SHAH Previous 36 GHABHARA SHRI AJITNÄTH ASHOK-DR. -

Bhagavata Purana

Bhagavata Purana abridged translation by Parama Karuna Devi new edition 2021 Copyright © 2016 Parama Karuna Devi All rights reserved. ISBN: 9798530643811 published by Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center E-mail: [email protected] Blog: www.jagannathavallabhavedicresearch.wordpress.com Website: www.jagannathavallabha.com Correspondence address: Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center At Piteipur, P/O Alasana, PS Chandanpur, 752012 Dist. Puri Orissa, India Table of Contents Preface 5 The questions of the sages 7 The teachings of Sukadeva on yoga 18 Conversation between Maitreya and Vidura 27 The story of Varaha 34 The teachings of Kapila 39 The sacrifice of Daksha 56 The story of Dhruva 65 The story of king Prithu 71 The parable of Puranjana 82 The story of Rishabha 90 The story of Jada Bharata 97 The structure of the universe 106 The story of Ajamila 124 The descendants of Daksha 128 Indra and Vritrasura 134 Diti decides to kill Indra 143 The story of Prahlada 148 The varnashrama dharma system 155 The story of Gajendra 163 The nectar of immortality 168 The story of Vamana 179 The descendants of Sraddhadeva Manu 186 The story of Ambarisha 194 The descendants of Ikshvaku 199 The story of Rama 206 The dynastyof the Moon 213 Parama Karuna Devi The advent of Krishna 233 Krishna in the house of Nanda 245 The gopis fall in love with Krishna 263 Krishna dances with the gopis 276 Krishna kills more Asuras 281 Krishna goes to Mathura 286 Krishna builds the city of Dvaraka 299 Krishna marries Rukmini 305 The other wives of Krishna 311 The -

Lalitha Sahasranamam

THE LALITHA SAHASRANAMA FOR THE FIRST TIME READER BY N.KRISHNASWAMY & RAMA VENKATARAMAN THE UNIVERSAL MOTHER A Vidya Vrikshah Publication ` AUM IS THE SYMBOL OF THAT ETERNAL CONSCIOUSNESS FROM WHICH SPRINGS THY CONSCIOUSNESS OF THIS MANIFESTED EXISTENCE THIS IS THE CENTRAL TEACHING OF THE UPANISHADS EXPRESSED IN THE MAHAVAKYA OR GREAT APHORISM tt! Tv< Ais THIS SAYING TAT TVAM ASI TRANSLATES AS THAT THOU ART Dedication by N.Krishnaswamy To the Universal Mother of a Thousand Names ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Dedication by Rama Venkataraman To my revered father, Sri.S.Somaskandan who blessed me with a life of love and purpose ACKNOWLEDGEMENT Our gratitude to Alamelu and C.L.Ramakrishanan for checking the contents to ensure that they we were free from errors of any kin d. The errors that remain are, of course, entirely ours. THE LALITHA SAHASRANAMA LIST OF CONTENTS TOPICS Preface Introduction The Lalitha Devi story The Sri Chakra SLOKA TEXT : Slokas 1 -10 Names 1 - 26 Slokas 11 -20 Names 27 - 48 Slokas 21 -30 Names 49 - 77 Slokas 31 -40 Names 78 - 111 Slokas 41 -50 Names 112 - 192 Slokas 51 -60 Names 193 - 248 Slokas 61 -70 Names 249 - 304 Slokas 71 -80 Names 305 - 361 Slokas 81 -90 Names 362 - 423 Slokas 91 -100 Names 424 - 490 Slokas 101 -110 Names 491 - 541 Slokas 111 -120 Names 542 - 600 Slokas 121 -130 Names 601 - 661 Slokas 141 -140 Names 662 - 727 Slokas 141 -150 Names 728 - 790 Slokas 151 -160 Names 791 - 861 Slokas 161 -170 Names 862 - 922 Slokas 171 -183 Names 923 - 1000 Annexure : Notes of special interest ------------------------------------------------------------ Notes : 1. -

FT Pathshala Curriculum 2018-19.Xlsx

Stuti/Chaitya One time Grade Sutra Story Philosophy Activities Vandan/Stavan/Thoy Activity/Project Respect Teachers and Parents; Bhagwan and Chand Bow down to parents & elders; Pre-KG 1.Navkar Stuti- Prabhu Darshan Eight Kinds of Puja; 5 Khamasamna on kaushik, Past bhav of Bed time prayers (Shiyal Mara 3-4 3.Khamasamno 1st stanza 24 Tirthankar Names Gyan Pnchami Chand kaushik Santhare- Navkar tu maro bhai); Basic living non-living games How to hold Navkarvali; Goval Puts nails in Introduction to Jain Vocabulary Bhagvan's Ears; Due to like Jai Jinendra, Pranam, Pre-KG 2.Panchindiya Stuti- Prabhu Darshan Bhagvan's Karma During Bhagvan NavAngi 5 Khamasamna on Tirthankar, Puja, Aarti, Derasar, 4-5 4.Icchakar stanza 1 to 3 Tripristha Vasudev Bhav Puja Gyan Pnchami Upashray, Maharaj Saheb, (Putting Lead in Door Sadhviji etc.; Coloring and keeper's Ear) naming Lanchhans & Swapnas Stuti- Prabhu Darshan stanza 1 to 4; Shrimate Virnathay; Siddharath 5.Abhuthio Mahavir Swami Nirvan, Sut Vandie Tirthankar Names and KG 6.Iriya vahiyam Gautam Swami Keval To Dehrasar Activity Book (Chaityavandan), Din Lanchhans 7.Tassa uttari gyan, Bhaibij Dukhiyano Tu chhe beli (Stavan), Mahavir Jinanda (Thoy) Stuti- Prabhu Darshan stanza 1 to 6; Kamathe Dharnendra, Jai 8.Anathha Parshwanath Bhagvan and Activity Book and Alphabets A to 1 Chintamani Parshwanath Guruvandan Vidhi To Dehrasar 9.Loggas Kamath M (Chaitya vandan), Tu Prabhu Maro (Stavan), Pas Jinanda (Thoy) Stuti/Chaitya One time Grade Sutra Story Philosophy Activities Vandan/Stavan/Thoy Activity/Project -

The Complete Mahabharata in a Nutshell

Contents Introduction Dedication Chapter 1 The Book of the Beginning 1.1 Vyasa (the Composer) and Ganesha (the Scribe) 1.2 Vyasa and his mother Sathyavathi 1.3 Janamejaya’s Snake Sacrifice (Sarpasastra) 1.4 The Prajapathis 1.5 Kadru, Vinatha and Garuda 1.6 The Churning of the Ocean of Milk 1.7 The Lunar and Solar races 1.8 Yayathi and his wives Devayani and Sharmishta 1.9 Dushyanta and Shakuntala 1.10 Parashurama and the Kshatriya Genocide BOOKS 1.11 Shanthanu, Ganga and their son Devavratha 1.12 Bhishma, Sathyavathi and Her Two Sons 1.13 Vyasa’s Sons: Dhritharashtra,DC Pandu and Vidura 1.14 Kunthi and her Son Karna 1.15 Birth of the Kauravas and the Pandavas 1.16 The Strife Starts 1.17 The Preceptors Kripa and Drona 1.18 The Autodidact Ekalavya and his Sacrifice 1.19 Royal Tournament where Karna became a King 1.20 Drona’s Revenge on Drupada and its Counterblow 1.21 Lord Krishna’s Envoy to Hasthinapura 1.22 The Story of Kamsa 1.23 The Wax Palace Inferno 1.24 Hidimba, Hidimbi and Ghatotkacha 1.25 The Ogre that was Baka 1.26 Dhaumya, the Priest of the Pandavas 1.27 The Feud between Vasishta and Vishwamithra 1.28 More on the Quality of Mercy 1.29 Draupadi, her Five Husbands and Five Sons 1.30 The Story of Sunda and Upasunda 1.31 Draupadi’s Previous Life 1.32 The Pandavas as the Incarnation of the Five Indras 1.33 Khandavaprastha and its capital Indraprastha 1.34 Arjuna’s Liaisons while on Pilgrimage 1.35 Arjuna and Subhadra 1.36 The Khandava Conflagaration 1.37 The Strange Story of the Sarngaka Birds Chapter 2 The Book of the Assembly Hall