Holstun Antigone Becomes Jocasta.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LE MONDE/PAGES<UNE>

www.lemonde.fr 58 ANNÉE – Nº 17830 – 1,20 ¤ – FRANCE MÉTROPOLITAINE --- VENDREDI 24 MAI 2002 FONDATEUR : HUBERT BEUVE-MÉRY – DIRECTEUR : JEAN-MARIE COLOMBANI 0123 A Moscou, DES LIVRES L’école de Luc Ferry Bush et Poutine Roberto Calasso Grecs à Montpellier Illettrisme, enseignement professionnel, autorité : les trois priorités du ministre de l’éducation consacrent un Le cinéma et l’écrit LE NOUVEAU ministre de l’édu- f rapprochement cation nationale, Luc Ferry, expose Un entretien avec INCENDIE dans un entretien au Monde ses le nouveau ministre « historique » trois priorités : la lutte contre l’illet- de la jeunesse L’ambassade d’Israël trisme, la valorisation de l’enseigne- ment professionnel et la consolida- et de l’éducation LORS de sa première visite officiel- à Paris détruite dans la tion de l’autorité des professeurs, le en Russie, le président américain nuit. Selon la police, le qu’il lie à la sécurité. Pour l’illettris- George W. Bush signera avec Vladi- me, Luc Ferry reproche à ses prédé- f « Il faut revaloriser mir Poutine, vendredi 24 mai au feu était accidentel p. 11 cesseurs de n’avoir « rien fait Kremlin, un traité de désarmement depuis dix ans ». Il insiste sur le res- la pédagogie nucléaire qualifié d’« historique » et MAFIA pect des horaires de lecture et du travail » à l’école visant à « mettre fin à la guerre froi- d’écriture, ainsi que sur la prise en de ». Les deux pays s’engagent à Dix ans après la mort charge des jeunes en difficulté. réduire leurs arsenaux stratégiques à L’enseignement professionnel doit f Médecins : un niveau maximal de 2 200 ogives à du juge Falcone p. -

Download-To-Own and Online Rental) and Then to Subscription Television And, Finally, a Screening on Broadcast Television

Exporting Canadian Feature Films in Global Markets TRENDS, OPPORTUNITIES AND FUTURE DIRECTIONS MARIA DE ROSA | MARILYN BURGESS COMMUNICATIONS MDR (A DIVISION OF NORIBCO INC.) APRIL 2017 PRODUCED WITH THE ASSISTANCE OF 1 EXPORTING CANADIAN FEATURE FILMS IN GLOBAL MARKETS Acknowledgements This study was commissioned by the Canadian Media Producers Association (CMPA), in partnership with the Association québécoise de la production médiatique (AQPM), the Cana- da Media Fund (CMF), and Telefilm Canada. The following report solely reflects the views of the authors. Findings, conclusions or recom- mendations expressed in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the funders of this report, who are in no way bound by any recommendations con- tained herein. 2 EXPORTING CANADIAN FEATURE FILMS IN GLOBAL MARKETS Executive Summary Goals of the Study The goals of this study were three-fold: 1. To identify key trends in international sales of feature films generally and Canadian independent feature films specifically; 2. To provide intelligence on challenges and opportunities to increase foreign sales; 3. To identify policies, programs and initiatives to support foreign sales in other jurisdic- tions and make recommendations to ensure that Canadian initiatives are competitive. For the purpose of this study, Canadian film exports were defined as sales of rights. These included pre-sales, sold in advance of the completion of films and often used to finance pro- duction, and sales of rights to completed feature films. In other jurisdictions foreign sales are being measured in a number of ways, including the number of box office admissions, box of- fice revenues, and sales of rights. -

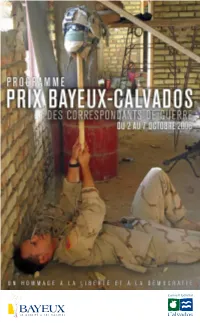

Programme-2006.Pdf

Programme PRIX BAYEUX-CALVADOS Édition 2006 DES CORRESPONDANTS DE GUERRE 2006 Lundi 2 octobre P Prix des lycéens J’ai le plaisir de vous Basse-Normandie présenter la 13e édition Mardi 3 octobre du Prix Bayeux-Calvados P Cinéma pour les collégiens des Correspondants de Guerre. Mercredi 4 octobre P Ouverture des expositions Fenêtre ouverte sur le monde, sur ses conflits, sur les difficultés du métier d’informer, Jeudi 5 octobre ce rendez-vous majeur des médias internationaux et du public rappelle, d’année en année, notre attachement à la démocratie et à son expression essentielle : P Soirée grands reporters : la liberté de la presse. Liban, nouveau carrefour Les débats, les projections et les expositions proposés tout au long de cette semaine de tous les dangers offrent au public et notamment aux jeunes l’éclairage de grands reporters et le décryptage d’une actualité internationale complexe et souvent dramatique. Vendredi 6 octobre Cette année plus que jamais, Bayeux témoignera de son engagement en inaugurant P Réunion du jury avec Reporters sans frontières, le « Mémorial des Reporters », site unique en Europe, international dédié aux journalistes du monde entier disparus dans l’exercice de leur profession pour nous délivrer une information libre, intègre et sincère. P Soirée hommage et projection en avant-première J’invite chacune et chacun d’entre vous à venir nous rejoindre du 2 au 7 octobre du film “ L’Étoile du Soldat ” à Bayeux, pour partager cette formidable semaine d’information, d’échange, d’hommage et d’émotion. de Christophe De Ponfilly PATRICK GOMONT Samedi 7 octobre Maire de Bayeux P Réunion du jury international et du jury public P Inauguration du Mémorial des reporters avec Reporters sans frontières P Salon du livre VOUS Le Prix du public, catégorie photo, aura lieu le samedi 7 octobre, de 10 h à 11 h, à la Halle aux Grains P SOUHAITEZ Table ronde sur la sécurité de Bayeux. -

Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research

University of Alberta The Performance of Identity in Wajdi Mouawad’s Incendies by Nicole Renault A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Drama ©Nicole Renault Fall 2009 Edmonton, Alberta Permission is hereby granted to the University of Alberta Libraries to reproduce single copies of this thesis and to lend or sell such copies for private, scholarly or scientific research purposes only. Where the thesis is converted to, or otherwise made available in digital form, the University of Alberta will advise potential users of the thesis of these terms. The author reserves all other publication and other rights in association with the copyright in the thesis and, except as herein before provided, neither the thesis nor any substantial portion thereof may be printed or otherwise reproduced in any material form whatsoever without the author's prior written permission. Library and Archives Bibliothèque et Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de l’édition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-54187-6 Our file Notre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-54187-6 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non- L’auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant à la Bibliothèque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par télécommunication ou par l’Internet, prêter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des thèses partout dans le loan, distribute and sell theses monde, à des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non- support microforme, papier, électronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. -

Press Kit Directed by Written and Uawad Wajdi Mou

Press Kit written and directed by Wajdi Mouawad 5 — 30 December 2018 Contact details Dorothée Duplan, Flore Guiraud, Camille Pierrepont assisted by Louise Dubreil 01 48 06 52 27 | [email protected] Downloadable Press kit and photos: www.colline.fr > professionnels > bureau de presse 2 Tous des oiseaux 5 – 30 December 2018 at La Colline – théâtre national Show in German, English, Arabic, and Hebrew surtitled in French duration: 4h interval included Cast and Creative Text and stage direction Wajdi Mouawad with Jalal Altawil Wazzan Jérémie Galiana or Daniel Séjourné Eitan Victor de Oliveira the waiter, the Rabbi, the doctor Leora Rivlin Leah Judith Rosmair or Helene Grass Norah Darya Sheizaf Eden, the nurse Rafael Tabor Etgar Raphael Weinstock David Souheila Yacoub or Nelly Lawson Wahida Assistant director Valérie Nègre Dramaturgy Charlotte Farcet Artistic collaboration François Ismert Historical advisor Natalie Zemon Davis Original music Eleni Karaindrou Set design Emmanuel Clolus Lighting design Éric Champoux Sound design Michel Maurer Costume design Emmanuelle Thomas assisted by Isabelle Flosi Make-up and hair design Cécile Kretschmar Hebrew translation Eli Bijaoui English translation Linda Gaboriau English translation Uli Menke Arabic translation Jalal Altawil 2018 Production La Colline – théâtre national The show was created on Novembre 17th in the Main venue at La Colline and has received the Great Prize 2018 of the Professional Review Association. The text has been published by Léméac/Actes Sud-Papiers in January 2018. 3 On tour -

The Doolittle Family in America, 1856

TheDoolittlefamilyinAmerica WilliamFrederickDoolittle,LouiseS.Brown,MalissaR.Doolittle THE DOOLITTLE F AMILY IN A MERICA (PART I V.) YCOMPILED B WILLIAM F REDERICK DOOLITTLE, M. D. Sacred d ust of our forefathers, slumber in peace! Your g raves be the shrine to which patriots wend, And swear tireless vigilance never to cease Till f reedom's long struggle with tyranny end. :" ' :,. - -' ; ., :; .—Anon. 1804 Thb S avebs ft Wa1ts Pr1nt1ng Co., Cleveland Look w here we may, the wide earth o'er, Those l ighted faces smile no more. We t read the paths their feet have worn, We s it beneath their orchard trees, We h ear, like them, the hum of bees And rustle of the bladed corn ; We turn the pages that they read, Their w ritten words we linger o'er, But in the sun they cast no shade, No voice is heard, no sign is made, No s tep is on the conscious floor! Yet Love will dream and Faith will trust (Since He who knows our need is just,) That somehow, somewhere, meet we must. Alas for him who never sees The stars shine through his cypress-trees ! Who, hopeless, lays his dead away, \Tor looks to see the breaking day \cross the mournful marbles play ! >Vho hath not learned in hours of faith, The t ruth to flesh and sense unknown, That Life is ever lord of Death, ; #..;£jtfl Love" ca:1 -nt ver lose its own! V°vOl' THE D OOLITTLE FAMILY V.PART I SIXTH G ENERATION. The l ife given us by Nature is short, but the memory of a well-spent life is eternal. -

Young Adult Realistic Fiction Book List

Young Adult Realistic Fiction Book List Denotes new titles recently added to the list while the severity of her older sister's injuries Abuse and the urging of her younger sister, their uncle, and a friend tempt her to testify against Anderson, Laurie Halse him, her mother and other well-meaning Speak adults persuade her to claim responsibility. A traumatic event in the (Mature) (2007) summer has a devastating effect on Melinda's freshman Flinn, Alexandra year of high school. (2002) Breathing Underwater Sent to counseling for hitting his Avasthi, Swati girlfriend, Caitlin, and ordered to Split keep a journal, A teenaged boy thrown out of his 16-year-old Nick examines his controlling house by his abusive father goes behavior and anger and describes living with to live with his older brother, his abusive father. (2001) who ran away from home years earlier under similar circumstances. (Summary McCormick, Patricia from Follett Destiny, November 2010). Sold Thirteen-year-old Lakshmi Draper, Sharon leaves her poor mountain Forged by Fire home in Nepal thinking that Teenaged Gerald, who has she is to work in the city as a spent years protecting his maid only to find that she has fragile half-sister from their been sold into the sex slave trade in India and abusive father, faces the that there is no hope of escape. (2006) prospect of one final confrontation before the problem can be solved. McMurchy-Barber, Gina Free as a Bird Erskine, Kathryn Eight-year-old Ruby Jean Sharp, Quaking born with Down syndrome, is In a Pennsylvania town where anti- placed in Woodlands School in war sentiments are treated with New Westminster, British contempt and violence, Matt, a Columbia, after the death of her grandmother fourteen-year-old girl living with a Quaker who took care of her, and she learns to family, deals with the demons of her past as survive every kind of abuse before she is she battles bullies of the present, eventually placed in a program designed to help her live learning to trust in others as well as her. -

1997 Sundance Film Festival Awards Jurors

1997 SUNDANCE FILM FESTIVAL The 1997 Sundance Film Festival continued to attract crowds, international attention and an appreciative group of alumni fi lmmakers. Many of the Premiere fi lmmakers were returning directors (Errol Morris, Tom DiCillo, Victor Nunez, Gregg Araki, Kevin Smith), whose earlier, sometimes unknown, work had received a warm reception at Sundance. The Piper-Heidsieck tribute to independent vision went to actor/director Tim Robbins, and a major retrospective of the works of German New-Wave giant Rainer Werner Fassbinder was staged, with many of his original actors fl own in for forums. It was a fi tting tribute to both Fassbinder and the Festival and the ways that American independent cinema was indeed becoming international. AWARDS GRAND JURY PRIZE JURY PRIZE IN LATIN AMERICAN CINEMA Documentary—GIRLS LIKE US, directed by Jane C. Wagner and LANDSCAPES OF MEMORY (O SERTÃO DAS MEMÓRIAS), directed by José Araújo Tina DiFeliciantonio SPECIAL JURY AWARD IN LATIN AMERICAN CINEMA Dramatic—SUNDAY, directed by Jonathan Nossiter DEEP CRIMSON, directed by Arturo Ripstein AUDIENCE AWARD JURY PRIZE IN SHORT FILMMAKING Documentary—Paul Monette: THE BRINK OF SUMMER’S END, directed by MAN ABOUT TOWN, directed by Kris Isacsson Monte Bramer Dramatic—HURRICANE, directed by Morgan J. Freeman; and LOVE JONES, HONORABLE MENTIONS IN SHORT FILMMAKING directed by Theodore Witcher (shared) BIRDHOUSE, directed by Richard C. Zimmerman; and SYPHON-GUN, directed by KC Amos FILMMAKERS TROPHY Documentary—LICENSED TO KILL, directed by Arthur Dong Dramatic—IN THE COMPANY OF MEN, directed by Neil LaBute DIRECTING AWARD Documentary—ARTHUR DONG, director of Licensed To Kill Dramatic—MORGAN J. -

The Future of Lebanon Hearing Committee On

S. HRG. 106–770 THE FUTURE OF LEBANON HEARING BEFORE THE SUBCOMMITTEE ON NEAR EASTERN AND SOUTH ASIAN AFFAIRS OF THE COMMITTEE ON FOREIGN RELATIONS UNITED STATES SENATE ONE HUNDRED SIXTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION JUNE 14, 2000 Printed for the use of the Committee on Foreign Relations ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.access.gpo.gov/congress/senate U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 67–981 CC WASHINGTON : 2000 VerDate 11-MAY-2000 15:20 Dec 05, 2000 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 67981 SFRELA1 PsN: SFRELA1 COMMITTEE ON FOREIGN RELATIONS JESSE HELMS, North Carolina, Chairman RICHARD G. LUGAR, Indiana JOSEPH R. BIDEN, JR., Delaware CHUCK HAGEL, Nebraska PAUL S. SARBANES, Maryland GORDON H. SMITH, Oregon CHRISTOPHER J. DODD, Connecticut ROD GRAMS, Minnesota JOHN F. KERRY, Massachusetts SAM BROWNBACK, Kansas RUSSELL D. FEINGOLD, Wisconsin CRAIG THOMAS, Wyoming PAUL D. WELLSTONE, Minnesota JOHN ASHCROFT, Missouri BARBARA BOXER, California BILL FRIST, Tennessee ROBERT G. TORRICELLI, New Jersey LINCOLN D. CHAFEE, Rhode Island STEPHEN E. BIEGUN, Staff Director EDWIN K. HALL, Minority Staff Director SUBCOMMITTEE ON NEAR EASTERN AND SOUTH ASIAN AFFAIRS SAM BROWNBACK, Kansas, Chairman JOHN ASHCROFT, Missouri PAUL D. WELLSTONE, Minnesota GORDON H. SMITH, Oregon ROBERT G. TORRICELLI, New Jersey ROD GRAMS, Minnesota PAUL S. SARBANES, Maryland CRAIG THOMAS, Wyoming CHRISTOPHER J. DODD, Connecticut (II) VerDate 11-MAY-2000 15:20 Dec 05, 2000 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00002 Fmt 5904 Sfmt 5904 67981 SFRELA1 PsN: SFRELA1 CONTENTS Page Barakat, Colonel Charbel, South Lebanon Army; coordinator of the Civilian Committees, South Lebanon Refugees in Israel ............................................... -

The Israeli Experience in Lebanon, 1982-1985

THE ISRAELI EXPERIENCE IN LEBANON, 1982-1985 Major George C. Solley Marine Corps Command and Staff College Marine Corps Development and Education Command Quantico, Virginia 10 May 1987 ABSTRACT Author: Solley, George C., Major, USMC Title: Israel's Lebanon War, 1982-1985 Date: 16 February 1987 On 6 June 1982, the armed forces of Israel invaded Lebanon in a campaign which, although initially perceived as limited in purpose, scope, and duration, would become the longest and most controversial military action in Israel's history. Operation Peace for Galilee was launched to meet five national strategy goals: (1) eliminate the PLO threat to Israel's northern border; (2) destroy the PLO infrastructure in Lebanon; (3) remove Syrian military presence in the Bekaa Valley and reduce its influence in Lebanon; (4) create a stable Lebanese government; and (5) therefore strengthen Israel's position in the West Bank. This study examines Israel's experience in Lebanon from the growth of a significant PLO threat during the 1970's to the present, concentrating on the events from the initial Israeli invasion in June 1982 to the completion of the withdrawal in June 1985. In doing so, the study pays particular attention to three aspects of the war: military operations, strategic goals, and overall results. The examination of the Lebanon War lends itself to division into three parts. Part One recounts the background necessary for an understanding of the war's context -- the growth of PLO power in Lebanon, the internal power struggle in Lebanon during the long and continuing civil war, and Israeli involvement in Lebanon prior to 1982. -

YANA MEERZON This Essay Examines the Forms of History and Memory Representation in Incendies, the 2004 Play by Wajdi Mouawad, An

YANA MEERZON STAGING MEMORY IN WAJDI MOUAWAD ’S INCENDIES : ARCHAEOLOGICAL SITE OR POETIC VENUE ? This essay examines the forms of history and memory representation in Incendies , the 2004 play by Wajdi Mouawad, and its 2010 film version, directed by Denis Villeneuve. Incendies tells the story of a twin brother and sister on the quest to uncover the mystery of their mother’s past and the silence of her last years. A contemporary re-telling of the Oedipus myth, the play examines what kind of cultural, collective, and individual memo - ries inform the journeys of its characters, who are exilic children. The play serves Mouawad as a public platform to stage the testimony of his child - hood trauma: the trauma of war, the trauma of exilic adaptation, and the challenges of return. As this essay argues, when moved from one medium to another, Mouawad’s work forces the directors to seek its historical and geographical contextualization. If in its original staging, Incendies allows Mouawad to elevate the story of his personal suffering to the universals of abandoned childhood, to reach in its language the realms of poetic expres - sion, and to make memory a separate, almost tangible entity on stage, then the 2010 film version by Villeneuve turns this play into an archaeological site to excavate the recent history of a single war-torn Middle East country (supposedly Lebanon), an objective at odds with Mouawad’s own view of theatre as a venue where poetry meets politics. Naturally the transposition from a play to a film presupposes a significant mutation of the original and raises questions of textual fidelity. -

Wajdi Mouawad

Wajdi Mouawad Born in 1968, author, actor, and director Wajdi Mouawad spends his early childhood in Lebanon, his adolescence in France, and his young adult years in Quebec before settling in France, where he now lives. He studied in Montreal at École nationale de théâtre du Canada, and is awarded a diploma in performance in 1991. Upon graduation he begins codirecting his first company, Théâtre Ô Parleur, with actor Isabelle Leblanc. In 2005, he establishes two companies, Abé Carré Cé Carré, in Quebec, with Emmanuel Schwarts, and Au Carré de l’Hypoténuse in France. During this time, in 2000, he assumes the role of artistic director for the Théâtre de Quat’Sous in Montreal, a position he will hold for four seasons. He and his French company, Au Carré de l’Hypoténuse were associate artists at l'Espace Malraux, scène nationale de Chambéry et de la Savoie, from 2008 to 2010. In 2009 he is artist in residence of the 63rd edition of the Festival d’Avignon, where he stages the quartet Le Sang des Promesses. He serves as artistic director for the Théâtre français du Centre national des Arts d’Ottawa from 2007 to 2012. Since September 2011, he has been associated artist at the Grand T- Nantes. In April 2016, he is nominated to assume the role of director for the National Theater in Paris, La Colline. His career as stage director began with the Théâtre Ô Parleur, as he contributed his own works to be performed: Partie de cache-cache entre deux Tchécoslovaques au début du siècle (1991), Journée de noces chez les Cromagnons (1994) et Willy Protagoras enfermé dans les toilettes (1998), puis Ce n’est pas la manière qu’on se l’imagine que Claude et Jacqueline se sont rencontrés coécrit avec Estelle Clareton (2000).