Documentos De Trabajo DT-SEHA N

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

… Distr. GENERAL UNEP/CBD/RW/EBSA/WCAR/1/2

CBD Distr. GENERAL UNEP/CBD/RW/EBSA/WCAR/1/2 23 February 2012 ORIGINAL: ENGLISH WIDER CARIBBEAN AND WESTERN MID-ATLANTIC REGIONAL WORKSHOP TO FACILITATE THE DESCRIPTION OF ECOLOGICALLY OR BIOLOGICALLY SIGNIFICANT MARINE AREAS Recife, Brazil, 28 February –2 March 2012 COMPILATION OF SUBMISSIONS OF SCIENTIFIC INFORMATION TO DESCRIBE EBSAS IN THE WIDER CARIBBEAN AND WESTERN MID-ATLANTIC REGION Note by the Executive Secretary 1. The Executive Secretary is circulating herewith a compilation of submissions of scientific information to describe ecologically or biologically significant marine areas (EBSAs) in the Wider Caribbean and Western Mid-Atlantic region, submitted by Parties and organizations in response to notification 2012-001, dated 3 January 2012, for the information of participants in the Wider Caribbean and Western Mid-Atlantic Regional Workshop to Facilitate the Description of Ecologically or Biologically Significant Marine Areas, being convened by the Convention on Biological Diversity and hosted by the Government of Brazil in Recife, Brazil, from 28 February to 2 March 2012, in collaboration with the Caribbean Environment Programme (CEP), with financial support from the European Union. 2. This compilation consists of the following: (a) A list of submissions made by Parties and organizations. The original submissions are available athttp://www.cbd.int/doc/?meeting=RWEBSA-WCAR-01. The list is divided into two parts: the first table contains submissions of potential areas that meet EBSA criteria, most utilizing the template provided for that purpose in the above notification; the second consists of supporting documentation; and (b) A background document entitled "Data to inform the Wider Caribbean and Western Mid- Atlantic Regional Workshop to Facilitate the Description of Ecologically or Biologically Significant Marine Areas”, which was prepared by the Marine Geospatial Ecology Lab, Duke University, with financial support from the European Union, in support of the CBD Secretariat in its technical preparation for the above-mentioned regional workshop. -

Policy Lessons from History and Natural Resource Projects in Rural Haiti

POLICY LESSONS FROM HISTORY AND NATURAL RESOURCE PROJECTS IN RURAL HAITI By T. Anderson White Working Paper No. 17, 58 Pages, November 1994 PN-ABU-097 For more information, contact T. Anderson White Department of Forest Resources 115 Green Hall University of Minnesota 1530 North Cleveland Avenue St. Paul, MN USA 55108 Tel: (612) 624-1224 Fax: (612) 625-5212 For copies of this publication, contact Ellen A. Maurer Communications Director EPAT/MUCIA Research & Training University of Wisconsin-Madison 1003 WARF Office Building 610 Walnut Street Madison, WI USA 53705-2397 Tel: (608) 263-4781 Fax: (608) 265-2993 Email: [email protected] Edited by Ellen Maurer Layout by Sharon Graham and Lesa Langan * Some figures and/or tables included in the printed version of this publication could not be included in this electronic version. If you need copies of these figures or tables, please contact the author. PROJECT INFORMATION A USAID-funded global program, the Environmental and Natural Resources Policy and Training Project (EPAT), is implemented, in part, by 15 universities and development organizations through the Midwest Universities Consortium for International Activities, Inc. (MUCIA). EPAT/MUCIA has research, training, and communication components that offer the latest information about: * Energy, Industry & the Urban Environment * Forestry & Watershed Management * Macroeconomic Policy * Population & the Environment * Institutions & Policy Implementation * Environmental Policy Training * Environmental Policy Communications EPAT/MUCIA publications include: * Policy Briefs - short overviews of environmental policy concerns * Case Studies - outlining specific in-country policy challenges * Manuals - how-to-do-it environmental policy handbooks for easy reference * Working Papers - of environmental policy research in progress * Monographs - detailing the state of knowledge in particular subject matter areas. -

Selection of Melter Systems for the DOE/Lndustrial Center for Waste Vitrification Research (U)

WSRC-TR-93-762 Selection of Melter Systems for the DOE/lndustrial Center for Waste Vitrification Research (U) by D. F. Bickford Westinghouse Savannah River Company Savannah River Site Aiken, South Carolina 29808 DOE Contract No. DE-AC09-89SR18035 This paper was prepared in connection with work done under the above contract number with the U. S. Department of Energy. By acceptance of this paper, the publisher and/or recipient acknowledges the U. S. Government's right to retain a nonexclusive, royalty-free license in and to any copyright covering this paper, along with the right to reproduce and to authorize others to reproduce all or part of the copyrighted paper. tXSTRIBUTTON OFTHiS-OOOUMENJ.IS UNLIMITED WSRC-TR-93-762 SELECTION OF MELTER SYSTEMS FOR THE DOE/INDUSTRIAL CENTER FOR WASTE VITRIFICATION RESEARCH (U) Dennis F. Bickford, Advisory Scientist Westinghouse Savannah River Co., Savannah River Technology Center, Aiken, SC 29802. Author's signature DISCLAIMER Portions of this document may be illegible in electronic image products. Images are produced from the best available original document. DISCLAIMER This report was prepared as an account of work sponsored by an agency of the United States Government. Neither the United States Government nor any agency thereof, nor any of their employees, makes any warranty, express or implied, or assumes any legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of any information, apparatus, product, or process disclosed, or represents that its use would not infringe privately owned rights. Reference herein to any specific commercial product, process, or service by trade name, trademark, manufacturer, or otherwise does not necessarily constitute or imply its endorsement, recommendation, or favoring by the United States Government or any agency thereof. -

Department of Geography and Geology

DEPARTMENT OF GEOGRAPHY AND GEOLOGY ProfessorDavidBarker,BSc Wales, PhD Bristol, DipUrb&RegStudies Birmingham –HeadofDepartment WORKOFTHEDEPARTMENT The Department of Geography and Geology continued to mount a full programme of undergraduate teaching and postgraduate supervision in spite of the challenges imposed by budget and physical resources (space and equipment) and uncertainties created by academic staff resignations, vacancies that remained unfilled, and imminent staff retirements in Geology. Professor Trevor Jackson retired at the end of the academic year. Dr David Dodman resigned and departed Jamaica at the beginning of the second semester, and Dr Susan Mains was on maternity leave during that semester. Mr Kevon Rhiney was appointed as Temporary Assistant Lecturer in Geography from January to the end of the academic year to help us throughthisdifficultperiod. Student numbers in Geology continued to increase dramatically. Student enrolment in first year was 40 per cent higher than in 2006/07, while enrolment in second year was 30 per cent larger. These increased numbers created serious difficulties for staff in practical classes, and an acute shortage of microscopes needed to be urgently addressed. First year and final year numbers in Geography were comparable to those of the previous year, but second year numbers were slightly down as the impact of the abnormally small entry from the Faculty of Humanities andEducationin2006/07workeditswaythroughthesystem. The Department participated in the University’s 60th anniversary celebrations by organizing and hosting a highly successful international conference between July 7 and 11 on the theme “Foundations and Directions: Celebrating Geography at the University of the West 268 Indies.” The organizing committee was chaired by Dr David Miller, and 39 papers were presented at the meeting, 24 of which were presented by current or past members of the Department, including postgraduate students. -

STUDIES in the COMUNERO REVOLUTION L52()"'15Zl

STUDIES IN THE COMUNERO REVOLUTION l52()"'15zl HISTORY HONORS BY JIM AMELANG April 18, 1974 No teniamos Rey sino un bobo, e que el diablo av{a traydo a la Emperatriz a Castilla, ~ue era una bivora como su abuela la qual aV2a traydo esta mala ventura de Inquisicidn a Castilla e que ella la sustentava. Que plu guiese a Dios que viniese de Francia guerras o que duraran las Comunidades para que des truiran la Inquisicitn que los tenia echado a perder a todos ••• PEDRO CAZALLA , l A ~JECESSARY INrRODUCTION My attention was drawn to the problem of the revolution of the Comunidades by a chance rereading of the Bible of Hispanic history, Sr. Jaime Vicens Vives' Approaches to the History of Spain (cf. Bibliography). Sr. Vicens notes in his discussion of sixteenth-century r,astil1e that onB of the Itnoble elements" that was IIpruned!l by the rising orthodoxy Vias "the bourgeois ideal in the War of the Comunidades" (p. 97). My suspicions were immediately aroused by this remark, as I have always deferred to J.H. Elliott's characterization of the Comuneros as traditionalist, quasi-feudal reactionaries. A hasty perusal of Elliott (cf. Bibliography) failed to resolve the contradiction: an~ having smelled a rat, I began to do pre1iminarJ research on the Comuneros. I soon found that serious scholarly investigation of the subject had been carried out by only a handful of historians. This is not to say that Spanish historians and other Hispanists had overlooked the Comunidades-- far from the contrary. However, it was quite apparent that the revolt/revolution of the Comuneros was one of those lamen- table historical events which are often commented upon but very rarely under- stood. -

2020–21 Commencement Program

Commencement UNIVERSITY OF COLORADO BOULDER MAY 6, 2021 One Hundred Forty-Fifth Year of the University NORLIN CHARGE TO THE GRADUATES The first commencement at the University of Colorado was held for six graduates on June 8, 1882, in the chapel of Old Main. It was not until 40 years later, on September 4, 1922, that the first summer commencement was held. Since the first commencement in 1882, the University of Colorado Boulder has awarded more than 350,000 degrees. The traditional Norlin Charge to the graduates was first read by President George Norlin to the June 1935 graduating class. You are now certified to the world at large as alumni of the university. She is your kindly mother and you her cherished sons and daughters. This exercise denotes not your severance from her, but your union with her. Commencement does not mean, as many wrongly think, the breaking of ties and the beginning of life apart. Rather it marks your initiation in the fullest sense into the fellowship of the university, as bearers of her torch, as centers of her influence, as promoters of her spirit. The university is not the campus, not the buildings on campus, not the faculties, not the students of any one time—not one of these or all of them. The university consists of all who come into and go forth from her halls, who are touched by her influence, and who carry on her spirit. Wherever you go, the university goes with you. Wherever you are at work, there is the university at work. -

2008 XTERRA Maui Press Guide:2007 XTERRA Maui Press Guide.Qxd.Qxd

2008 PRESS GUIDE XTERRA WORLD CHAMPIONSHIP SPONSORS The XTERRA World Championship is presented by Paul Mitchell, XTERRA Gear.com, Hawaiian Airlines, the Maui Visitors Bureau and Maui Prince Hotel. Sponsors include GU, Gatorade, Zorrel, Breeder’s Choice, Kona Brewing Company, Rodale, and the Hawaii Tourism Authority. THE 13TH ANNUAL XTERRA WORLD CHAMPIONSHIP . The XTERRA World Championship is the final stop on the XTERRA Global Tour - a national and international series of 100+ qualifying events held in Australia, Austria, Brazil, Czech Republic, France, Italy, Japan, New Zealand, Saipan, South Africa, United Kingdom, and United States. The course, considered XTERRA’s toughest, consists of a 1.5-kilometer rough water swim, a grueling 32km mountain bike on the lower slopes of Haleakala, and a 12km trail run. The field is limited to 550 competitors, including 80 pros, who represent the best off-road multisport athletes on the planet. They come from more than 20 countries & compete for one of the richest purses in multisport at $130,000. The award-winning TEAM TV crew will be on location to tele- vise all the action for a one-hour sports special that will air across the U.S. via national syndication starting in January of 2009. You can watch last year’s race show now at www.XTERRA.tv and get live coverage from Maui on raceday, Oct. 26th at 9am. TABLE OF CONTENTS Media Information . .4 Schedule of Events . .5 How to Watch Guide for Spectators . .6 World Championship Quick Facts . .7 XTERRA Makena Beach Trail Run . .8 XTERRA University, Paul Mitchell Cut-a-thon, GU Eco Team . -

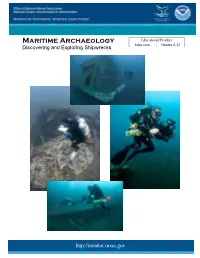

Maritime Archaeology—Discovering and Exploring Shipwrecks

Monitor National Marine Sanctuary: Maritime Archaeology—Discovering and Exploring Shipwrecks Educational Product Maritime Archaeology Educators Grades 6-12 Discovering and Exploring Shipwrecks http://monitor.noaa.gov Monitor National Marine Sanctuary: Maritime Archaeology—Discovering and Exploring Shipwrecks Acknowledgement This educator guide was developed by NOAA’s Monitor National Marine Sanctuary. This guide is in the public domain and cannot be used for commercial purposes. Permission is hereby granted for the reproduction, without alteration, of this guide on the condition its source is acknowledged. When reproducing this guide or any portion of it, please cite NOAA’s Monitor National Marine Sanctuary as the source, and provide the following URL for more information: http://monitor.noaa.gov/education. If you have any questions or need additional information, email [email protected]. Cover Photo: All photos were taken off North Carolina’s coast as maritime archaeologists surveyed World War II shipwrecks during NOAA’s Battle of the Atlantic Expeditions. Clockwise: E.M. Clark, Photo: Joseph Hoyt, NOAA; Dixie Arrow, Photo: Greg McFall, NOAA; Manuela, Photo: Joseph Hoyt, NOAA; Keshena, Photo: NOAA Inside Cover Photo: USS Monitor drawing, Courtesy Joe Hines http://monitor.noaa.gov Monitor National Marine Sanctuary: Maritime Archaeology—Discovering and Exploring Shipwrecks Monitor National Marine Sanctuary Maritime Archaeology—Discovering and exploring Shipwrecks _____________________________________________________________________ An Educator -

The Absence of America on the Early Modern Stage by Gavin R. Hollis A

The Absence of America on the Early Modern Stage by Gavin R. Hollis A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (English Language and Literature) in The University of Michigan 2008 Doctoral Committee: Professor Valerie J. Traub, Chair Professor Michael C. Schoenfeldt Associate Professor Susan M. Juster Associate Professor Susan Scott Parrish © Gavin Hollis 2008 To my parents ii Acknowledgements In an episode of The Simpsons, Marge urges Bart not to make fun of graduate students because “they’ve just made a terrible life choice.” This may be true, but one of the many advantages of this “life choice” is that I have met, been inspired by, and become firm friends with an array of people on both sides of the pond. The first debt I owe is to my advisors at the University of Michigan, who have seen this project through its many stages of confusion and incoherence. Mike Schoenfeldt, Scotti Parrish, and Sue Juster have been supportive, critical, rigorous, inventive, and excellent company. My biggest debt of gratitude is owed however to Valerie Traub, the chair of my dissertation committee, whose influence on this project and has been, and I hope will continue to be, immense. I’m also indebted to faculty at Trinity Hall, Cambridge and at The Shakespeare Institute who have shaped me as a scholar before I made it these shores. I am especially grateful to Peter Holland, who, it is no exaggeration to say, taught me how to read Shakespeare. Thank you also to John Jowett, Drew Milne, and John Lennard. -

Haitians: a People on the Move. Haitian Cultural Heritage Resource Guide

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 416 263 UD 032 123 AUTHOR Bernard, Marie Jose; Damas, Christine; Dejoie, Menes; Duval, Joubert; Duval, Micheline; Fouche, Marie; Marcellus, Marie Jose; Paul, Cauvin TITLE Haitians: A People on the Move. Haitian Cultural Heritage Resource Guide. INSTITUTION New York City Board of Education, Brooklyn, NY. Office of Bilingual Education. ISBN ISBN-1-55839-416-8 PUB DATE 1996-00-00 NOTE 176p. AVAILABLE FROM Office of Instructional Publications, 131 Livingston Street, Brooklyn, NY 11201. PUB TYPE Books (010) Guides Classroom Teacher (052) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC08 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Cultural Awareness; Cultural Background; Diversity (Student); Ethnic Groups; Foreign Countries; Haitian Creole; *Haitians; History; *Immigrants; Inservice Teacher Education; *Multicultural Education; Resource Materials; Teaching Guides; Teaching Methods; Urban Schools; *Urban Youth IDENTIFIERS Haiti; New York City Board of Education ABSTRACT This cultural heritage resource guide has been prepared as a tool for teachers to help them understand the cultural heritage of their Haitian students, their families, and their communities in order to serve them better. Although Haiti became an independent country in 1804, the struggle of its people for justice and freedom has never ended. Many Haitians have left Haiti for political, social, and economic reasons, and many have come to the larger cities of the United States, particularly New York City. This guide contains the following sections: (1) "Introduction"; (2) "Haiti at a Glance"; (3) "In Search of a Better Life";(4) "Haitian History"; (5) "Haitian Culture"; (6) "Images of Haiti"; and (7)"Bibliography," a 23-item list of works for further reading. (SLD) ******************************************************************************** * Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made * * from the original document. -

RF: Poster 01: Suture Tape Augmentation for Scapholunate Ligament Repair: a Biomechanical Study Category: Skin and Soft Tissue

RF: Poster 01: Suture Tape Augmentation for Scapholunate Ligament Repair: A Biomechanical Study Category: Skin and Soft Tissue Surgical Technique Level of Evidence: N/A Robert G. Thompson Joel Dustin D. Keith Roper Steven M. Kane Gary M. Lourie HYPOTHESIS The maximum load to failure of the scapholunate ligament repairs augmented with suture tape will be higher than the schapholunate ligament tears repaired solely with suture anchors.. METHODS Twelve fresh frozen cadavers (6 matched pairs) underwent a dorsal approach to the wrist and the scapholunate ligament was sharply dissected off of its scaphoid attachment. Six of the cadavers underwent direct repair of the SL ligament utilizing 2 suture anchors (2.2x4mm Micro Corkscrew FT Anchors). The other six cadavers underwent repair of the SL ligament with 2-0 FiberWire augmented with Fiber Tape (InternalBrace) utilizing 3.5 mm DX SwiveLock SL anchors. All specimens then underwent load to failure testing using tensile distraction forces applied by an Instron universal testing system (Instron, Canton, MA). The maximum load to failure and mode of failure were recorded. RESULTS The mean maximum load to failure for the suture anchor repair only group was 68 N with a standard deviation of 14.69. The mean maximum load to failure for the internal brace augmented group was 135 N with a standard deviation of 44.94. A p-value of 0.019 was calculated denoting a significantly higher max load to failure for the Internal Brace augmentation group compared to the repair only group (p< 0.05). Additionally, the mode at which each specimen failed at its maximum load point was recorded. -

2021 Primetime Emmy® Awards Ballot

2021 Primetime Emmy® Awards Ballot Outstanding Lead Actor In A Comedy Series Tim Allen as Mike Baxter Last Man Standing Brian Jordan Alvarez as Marco Social Distance Anthony Anderson as Andre "Dre" Johnson black-ish Joseph Lee Anderson as Rocky Johnson Young Rock Fred Armisen as Skip Moonbase 8 Iain Armitage as Sheldon Young Sheldon Dylan Baker as Neil Currier Social Distance Asante Blackk as Corey Social Distance Cedric The Entertainer as Calvin Butler The Neighborhood Michael Che as Che That Damn Michael Che Eddie Cibrian as Beau Country Comfort Michael Cimino as Victor Salazar Love, Victor Mike Colter as Ike Social Distance Ted Danson as Mayor Neil Bremer Mr. Mayor Michael Douglas as Sandy Kominsky The Kominsky Method Mike Epps as Bennie Upshaw The Upshaws Ben Feldman as Jonah Superstore Jamie Foxx as Brian Dixon Dad Stop Embarrassing Me! Martin Freeman as Paul Breeders Billy Gardell as Bob Wheeler Bob Hearts Abishola Jeff Garlin as Murray Goldberg The Goldbergs Brian Gleeson as Frank Frank Of Ireland Walton Goggins as Wade The Unicorn John Goodman as Dan Conner The Conners Topher Grace as Tom Hayworth Home Economics Max Greenfield as Dave Johnson The Neighborhood Kadeem Hardison as Bowser Jenkins Teenage Bounty Hunters Kevin Heffernan as Chief Terry McConky Tacoma FD Tim Heidecker as Rook Moonbase 8 Ed Helms as Nathan Rutherford Rutherford Falls Glenn Howerton as Jack Griffin A.P. Bio Gabriel "Fluffy" Iglesias as Gabe Iglesias Mr. Iglesias Cheyenne Jackson as Max Call Me Kat Trevor Jackson as Aaron Jackson grown-ish Kevin James as Kevin Gibson The Crew Adhir Kalyan as Al United States Of Al Steve Lemme as Captain Eddie Penisi Tacoma FD Ron Livingston as Sam Loudermilk Loudermilk Ralph Macchio as Daniel LaRusso Cobra Kai William H.