In the Army's Hands in the Army's Hands

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Election Impasse in Haiti

At a glance April 2016 The election impasse in Haiti The run-off in the 2015 presidential elections in Haiti has been suspended repeatedly, after the opposition contested the first round in October 2015. Just before the end of President Martelly´s mandate on 7 February 2016, an agreement was reached to appoint an interim President and a new Provisional Electoral Council, fixing new elections for 24 April 2016. Although most of the agreement has been respected , the second round was in the end not held on the scheduled date. Background After nearly two centuries of mainly authoritarian rule which culminated in the Duvalier family dictatorship (1957-1986), Haiti is still struggling to consolidate its own democratic institutions. A new Constitution was approved in 1987, amended in 2012, creating the conditions for a democratic government. The first truly free and fair elections were held in 1990, and won by Jean-Bertrand Aristide (Fanmi Lavalas). He was temporarily overthrown by the military in 1991, but thanks to international pressure, completed his term in office three years later. Aristide replaced the army with a civilian police force, and in 1996, when succeeded by René Préval (Inite/Unity Party), power was transferred democratically between two elected Haitian Presidents for the first time. Aristide was re-elected in 2001, but his government collapsed in 2004 and was replaced by an interim government. When new elections took place in 2006, Préval was elected President for a second term, Parliament was re-established, and a short period of democratic progress followed. A food crisis in 2008 generated violent protest, leading to the removal of the Prime Minister, and the situation worsened with the 2010 earthquake. -

USAID/OFDA Haiti Earthquake Program Maps 6/4/2010

EARTHQUAKE-AFFECTED AREAS AND POPULATION MOVEMENT IN HAITI CUBAEARTHQUAKE INTENSITY 73° W 72° W The Modified Mercalli (MMI) Intensity Scale* NORTHWESTNORTHWEST Palmiste N N 20° NORTHWEST 20° ESTIMATED MMI INTENSITY Port-de-Paix 45,862 Saint Louis Du Nord LIGHT SEVERE 4 8 Anse-a-foleur NORTH Jean Rabel 13,531 Monte Cristi 5 MODERATE 9 VIOLENT Le Borgne NORTHWESTNORTHWEST Cap-Haitien NORTHEAST 6 STRONG 10^ EXTREME Bassin-bleu Port-margot Quartier 8,500 Limbe Marin Caracol 7 VERY STRONG Baie-de-Henne Pilate Acul Plaine Phaeton Anse Rouge Gros Morne Limonade Fort-Liberte *MMI is a measure of ground shaking and is different Du Nord Du Nord from overall earthquake magnitude as measured Plaisance Trou-du-nord NORTHNORTH Milot Ferrier by the Richter Scale. Terre-neuve Sainte Suzanne ^Area shown on map may fall within MMI 9 Dondon Grande Riviera Quanaminthe classification, but constitute the areas of heaviest Dajabon ARTIBONITE Du Nord Perches shaking based on USGS data. Marmelade 162,509 Gonaives Bahon Source: USGS/PAGER Alert Version: 8 Ennery Saint-raphael NORTHEASTNORTHEAST HAITI EARTHQUAKE Vallieres Ranguitte Saint Michel Mont Organise 230,000 killed ARTIBONITEARTIBONITE De L'attalaye Pignon 196,595 injured La Victoire POPULATION MOVEMENT * 1,200,000 to 1,290,000 displaced CENTER Source: OCHA 02.22.10 Dessalines Cerca 3,000,000 affected Grande-Saline 90,997Carvajal * Population movements indicated include only Maissade Cerca-la-source individuals utilizing GoH-provided transportation *All figures are approximate. Commune Petite-riviere- Hinche and do not include people leaving Port-au-Prince population figures are as of 2003. de-l'artibonite utilizing private means of transport. -

United Nations Development Programme Country: Haiti PROJECT DOCUMENT

United Nations Development Programme Country: Haiti PROJECT DOCUMENT Project Title: Increasing resilience of ecosystems and vulnerable communities to CC and anthropic threats through a ridge to reef approach to BD conservation and watershed management ISF Outcome: 2.2: environmental vulnerability reduced and ecological potential developed for the sustainable management of natural and energy resources based on a decentralised territorial approach UNDP Strategic Plan Environment and Sustainable Development Primary Outcome: 3: mechanisms for climate change adaptation are in place Expected CP Outcomes: See ISF outcome Expected CPAP Output (s) 1. Priority watersheds have increased forest cover 2. National policies and plans for environmental and natural resource management integrating a budgeted action plan are validated 3. Climate change adaptation mechanisms are put in place. Executing Entity/Implementing Partner: Ministry of Environment Implementing Entity/Responsible Partners: United Nations Development Programme Brief Description This project will deliver help to reduce the vulnerability of poor people in Haiti to the effects of climate change, while at the same time conserving threatened coastal and marine biodiversity. Investments in climate- proofed and socially-sustainable BD conservation strategies, within the context of the National Protected Areas System (NPAS), will enable coastal and marine ecosystems to continue to generate Ecosystem-Based Adaptation (EBA) services; while additional investment of adaptation funds in the watersheds -

Bottom-Up Development in Haiti

Occasional Paper N° 5 Robert Earl Maguire Bottom-Up Development in Haiti Institute of Haitian Studies University of Kansas Occasional Paper N° 5 Bryant C. Freeman, Ph.D. General Editor Robert Earl Maguire Bottom-Up Development in Haiti Institute of Haitian Studies University of Kansas 1995 University of Kansas Institute of Haitian Studies Occasional Papers Bryant C. Freeman, Ph.D. - General Editor No 1 - Konstitisyon Repiblik Ayiti, 29 mas 1987. September 1994. Pp. vi-106. Haitian-language version (official orthography) of the present Constitution, as translated by Paul Déjean with the collaboration of Yves Déjean. Introduction in English. No 2 - Toussaint's Constitution (1801), with Introduction. October 1994. Pp. ix-20. In French. Introduction (in English) places Constitution in its historic context and analyzes salient features. No 3 - Bryant C. Freeman, Selected Critical Bibliography of English-Language Books on Haiti. February 1995 (Updated). Pp. 21. More than 150 entries, with brief description of each; special list of "Top Ten." Introduction and text in English. Updated periodically. No 4 - Strategy of Aristide Government for Social and Economic Reconstruction (August 1994). December 1994. Pp. iv-9. Official document setting forth recovery plan for Haiti. Introduction and text in English. No 5 - Robert Earl Maguire, Bottom-Up Development in Haiti. January 1995. Pp. iv-63. Keynote: develop people rather than things, with case study as carried out in Le Borgne. Introduction and text in English. N° 6 - Robert Earl Maguire, Devlopman Ki Soti nan Baz nan Peyi Dayiti. February 1995. Pp. v-71. Haitian-language version of N° 5, in Pressoir-Faublas orthography. -

Focus on Haiti

FOCUS ON HAITI CUBA 74o 73o 72o ÎLE DE LA TORTUE Palmiste ATLANTIC OCEAN 20o Canal de la Tortue 20o HAITI Pointe Jean-Rabel Port-de-Paix St. Louis de Nord International boundary Jean-Rabel Anse-à-Foleur Le Borgne Departmental boundary Monte Cap Saint-Nicolas Môle St.-Nicolas National capital Bassin-Bleu Baie de Criste NORD - OUEST Port-Margot Cap-Haïtien Mancenille Departmental seat Plaine Quartier Limbé du Nord Caracol Fort- Town, village Cap-à-Foux Bombardopolis Morin Liberté Baie de Henne Gros-Morne Pilate Acul Phaëton Main road Anse-Rouge du Nord Limonade Baie Plaisance Milot Trou-du-Nord Secondary road de Grande Terre-Neuve NORD Ferrier Dajabón Henne Pointe Grande Rivière du Nord Sainte Airport Suzanne Ouanaminthe Marmelade Dondon Perches Ennery Bahon NORD - EST Gonaïves Vallières 0 10 20 30 40 km Baie de Ranquitte la Tortue ARTIBONITE Saint- Raphaël Mont-Organisé 0 5 10 15 20 25 mi Pointe de la Grande-Pierre Saint Michel Baie de de l'Attalaye Pignon La Victoire Golfe de la Gonâve Grand-Pierre Cerca Carvajal Grande-Saline Dessalines Cerca-la-Source Petite-Rivière- Maïssade de-l'Artibonite Hinche Saint-Marc Thomassique Verrettes HAITI CENTRE Thomonde 19o Canal de 19o Saint-Marc DOMINICAN REPUBLIC Pointe Pointe de La Chapelle Ouest Montrouis Belladère Magasin Lac de ÎLE DE Mirebalais Péligre LA GONÂVE Lascahobas Pointe-à-Raquette Arcahaie Saut-d'Eau Baptiste Duvalierville Savenette Abricots Pointe Cornillon Jérémie ÎLES CAYÉMITES Fantasque Trou PRESQU'ÎLE Thomazeau PORT- É Bonbon DES BARADÈRES Canal de ta AU- Croix des ng Moron S Dame-Marie la Gonâve a Roseaux PRINCE Bouquets u Corail Gressier m Chambellan Petit Trou de Nippes â Pestel tr Carrefour Ganthier e Source Chaude Baradères Anse-à-Veau Pétion-Ville Anse d'Hainault Léogâne Fond Parisien Jimani GRANDE - ANSE NIPPES Petite Rivières Kenscoff de Nippes Miragoâne Petit-Goâve Les Irois Grand-Goâve OUEST Fonds-Verrettes L'Asile Trouin La Cahouane Maniche Camp-Perrin St. -

La Situation Politique Et Institutionnelle HAITI

HAITI 4 août 2016 La situation politique et institutionnelle Avertissement Ce document a été élaboré par la Division de l’Information, de la Documentation et des Recherches de l’Ofpra en vue de fournir des informations utiles à l’examen des demandes de protection internationale. Il ne prétend pas faire le traitement exhaustif de la problématique, ni apporter de preuves concluantes quant au fondement d’une demande de protection internationale particulière. Il ne doit pas être considéré comme une position officielle de l’Ofpra ou des autorités françaises. Ce document, rédigé conformément aux lignes directrices communes à l’Union européenne pour le traitement de l’information sur le pays d’origine (avril 2008) [cf. https://www.ofpra.gouv.fr/sites/default/files/atoms/files/lignes_directrices_europeennes.pdf ], se veut impartial et se fonde principalement sur des renseignements puisés dans des sources qui sont à la disposition du public. Toutes les sources utilisées sont référencées. Elles ont été sélectionnées avec un souci constant de recouper les informations. Le fait qu’un événement, une personne ou une organisation déterminée ne soit pas mentionné(e) dans la présente production ne préjuge pas de son inexistence. La reproduction ou diffusion du document n’est pas autorisée, à l’exception d’un usage personnel, sauf accord de l’Ofpra en vertu de l’article L. 335-3 du code de la propriété intellectuelle. Haïti : Situation politique et institutionnelle Table des matières 1. Panorama institutionnel, administratif et politique ................................................. 3 1.1. Les institutions .......................................................................................... 3 1.2. L’organisation administrative et territoriale ................................................... 3 1.3. Les principaux partis politiques .................................................................. -

Haiti Thirst for Justice

September 1996 Vol. 8, No. 7 (B) HAITI THIRST FOR JUSTICE A Decade of Impunity in Haiti I. SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS...........................................................................................................................2 II. IMPUNITY SINCE THE FALL OF THE DUVALIER FAMILY DICTATORSHIP ...........................................................7 The Twenty-Nine Year Duvalier Dictatorship Ends with Jean-Claude Duvalier's Flight, February 7, 1986.................7 The National Governing Council, under Gen. Henri Namphy, Assumes Control, February 1986 ................................8 Gen. Henri Namphy's Assumes Full Control, June 19, 1988.........................................................................................9 Gen. Prosper Avril Assumes Power, October 1988.....................................................................................................10 President Ertha Pascal Trouillot Takes Office, March 13, 1990 .................................................................................11 Jean-Bertrand Aristide Assumes Office as Haiti's First Democratically Elected President, February 7, 1991............12 Gen. Raul Cédras, Lt. Col. Michel François, and Gen. Phillippe Biamby Lead a Coup d'Etat Forcing President Aristide into Exile, Sept. 30, 1991 ...................................................................................13 III. IMPUNITY FOLLOWING PRESIDENT JEAN-BERTRAND ARISTIDE'S RETURN ON OCTOBER 15, 1994, AND PRESIDENT RENÉ PRÉVAL'S INAUGURATION ON FEBRUARY 7, 1996..............................................16 -

Assessment of Haitian Coffee Value Chain

Assessment of Haitian Coffee Value Chain Fernando Rodríguez, Nora Patricia Castañeda, Mark Lundy A participatory assessment of coffee chain actors in southern Haiti assessment Copyright © 2011 Catholic Relief Services Catholic Relief Services 228 West Lexington Street Baltimore, MD 21201-3413 USA Cover photo: Coffee plants in Haiti. CRS staff. Download this and other CRS publications at www.crsprogramquality.org Assessment of HAitiAn Coffee VAlue Chain A participatory assessment of coffee chain actors in southern Haiti July 12–August 30, 2010 Table of Contents Abbreviations and Acronyms . iii 1 Executive Summary. IV 2 Introduction. 1 3 Relevance of Coffee in Haiti. 1 4 Markets . 4 5 Coffee Chain Analysis. 5 6 Constraints Analyses. 17 7 Recommendations . 19 Glossary . 22 References . 24 Annexes . 25 Annex 1: Problem Tree. 25 Annex 2: Production Solution Tree. 26 Annex 3: Postharvest Solution Tree . 27 Annex 4: Marketing Solution Tree. 28 Annex 5: Conclusions Obtained with Workshops Participants. 29 Figures Figure 1: Agricultural sector participation in total GDP. 1 Figure 2: Coffee production. 3 Figure 3: Haitian coffee exports. 4 Figure 4: Coffee chain in southern Haiti. 6 Figure 5: Potential high-quality coffee municipalities in Haiti. 9 Tables Table 1: Summary of chain constraints and strategic objectives to address them. IV Table 2: Principal coffee growing areas and their potential to produce quality coffee. 2 Table 3: Grassroots organizations and exporting regional networks. 3 Table 4: Land distribution by plot size . 10 Table 5: Coffee crop area per department in 1995 . 10 Table 6: Organizations in potential high-quality coffee municipalities. 12 Table 7: Current and potential washed coffee production in the region . -

DG Haiti Info Brief 11 Feb 2010

IOMIOM EmergencyEmergency OperationsOperations inin HaitiHaiti InformationInformation BriefingBriefing forfor MemberMember StatesStates Thursday,Thursday, 1111 FebruaryFebruary 20102010 INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATION FOR MIGRATION 1 ObjectivesObjectives InIn thethe spiritspirit ofof “Member“Member StateState Ownership”:Ownership”: •• ToTo reportreport toto youyou onon howhow youryour moneymoney isis beingbeing spent.spent. •• ToTo demonstratedemonstrate IOM’sIOM’s activityactivity inin thethe UNUN ClusterCluster System.System. •• ToTo shareshare somesome impressionsimpressions fromfrom mymy recentrecent visitvisit toto HaitiHaiti (4-8(4-8 Feb)Feb) •• ToTo appealappeal forfor sustainedsustained supportsupport ofof Haiti.Haiti. INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATION FOR MIGRATION 2 OutlineOutline 1.1. SituationSituation inin HaitiHaiti 2.2. IOMIOM HaitiHaiti StaffingStaffing andand CapacityCapacity 3.3. EmergencyEmergency OperationsOperations andand PartnershipsPartnerships 4.4. DevelopmentDevelopment PlanningPlanning 5.5. ResourceResource MobilizationMobilization 6.6. ChallengesChallenges andand OpportunitiesOpportunities INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATION FOR MIGRATION 3 I.I. SituationSituation UpdateUpdate GreatestGreatest HumanitarianHumanitarian TragedyTragedy inin thethe WesternWestern HemisphereHemisphere 212,000212,000 dead;dead; 300,000300,000 injured;injured; 1.91.9 millionmillion displaceddisplaced (incl.(incl. 450,000450,000 children);children); 1.21.2 millionmillion livingliving inin spontaneousspontaneous settlementssettlements incl.incl. 700,000700,000 -

Hti Irma Snapshot 20170911 En.Pdf (English)

HAITI: Hurricane Irma – Humanitarian snapshot (as of 11 September 2017) Hurricane Irma, a category 5 hurricane hit Haiti on Thursday, September 7, 2017. On HAITI the night of the hurricane, 12,539 persons Injured people Bridge collapsed were evacuated to 81 shelters. To date, Capital: Port-au-Prince Severe flooding 6,494 persons remain in the 21 centers still Population: 10.9 M Damaged crops active. One life was lost and a person was recorded missing in the Centre Department Partially Flooded Communes while 17 people were injured in the Artibonite Damaged houses Injured people 6,494 Lachapelle departments of Nord, Nord-Ouest and Ouest. Damaged crops Grande Saline persons in River runoff or flooding of rivers caused Dessalines Injured people Saint-Marc 1 dead partial flooding in 22 communes in the temporary shelters Centre 1 missing person departments of Artibonite, Centre, Nord, Hinche Port de Paix out of 12,539 evacuated Cerca Cavajal Damaged crops Nord-Est, Nord-Ouest and Ouest. 4,903 Mole-St-Nicolas houses were flooded, 2,646 houses were Nord Limonade NORD-OUEST Cap-Haitien badly damaged, while 466 houses were Grande Rivière du Nord severely destroyed. Significant losses were Pilate Gros-Morne also recorded in the agricultural sector in the Nord-Est Bombardopolis Ouanaminthe Ouanaminthe (severe) NORD departments of Centre, Nord-Est and Fort-Liberté Gonaive Nord-Ouest. Caracol NORD-EST Ferrier Terrier-Rouge 21 The Haitian Government, with the support of Trou-du-Nord ARTIBONITE humanitarian partners, is already responding Nord-Ouest active Hinche in the relevant departments to help the Anse-à-Foleur Port-de-Paix affected population. -

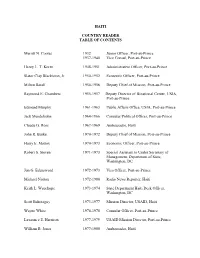

HAITI COUNTRY READER TABLE of CONTENTS Merritt N. Cootes 1932

HAITI COUNTRY READER TABLE OF CONTENTS Merritt N. Cootes 1932 Junior Officer, Port-au-Prince 1937-1940 Vice Consul, Port-au-Prince Henry L. T. Koren 1948-1951 Administrative Officer, Port-au-Prince Slator Clay Blackiston, Jr. 1950-1952 Economic Officer, Port-au-Prince Milton Barall 1954-1956 Deputy Chief of Mission, Port-au-Prince Raymond E. Chambers 1955-1957 Deputy Director of Binational Center, USIA, Port-au-Prince Edmund Murphy 1961-1963 Public Affairs Office, USIA, Port-au-Prince Jack Mendelsohn 1964-1966 Consular/Political Officer, Port-au-Prince Claude G. Ross 1967-1969 Ambassador, Haiti John R. Burke 1970-1972 Deputy Chief of Mission, Port-au-Prince Harry E. Mattox 1970-1973 Economic Officer, Port-au-Prince Robert S. Steven 1971-1973 Special Assistant to Under Secretary of Management, Department of State, Washington, DC Jon G. Edensword 1972-1973 Visa Officer, Port-au-Prince Michael Norton 1972-1980 Radio News Reporter, Haiti Keith L. Wauchope 1973-1974 State Department Haiti Desk Officer, Washington, DC Scott Behoteguy 1973-1977 Mission Director, USAID, Haiti Wayne White 1976-1978 Consular Officer, Port-au-Prince Lawrence E. Harrison 1977-1979 USAID Mission Director, Port-au-Prince William B. Jones 1977-1980 Ambassador, Haiti Anne O. Cary 1978-1980 Economic/Commercial Officer, Port-au- Prince Ints M. Silins 1978-1980 Political Officer, Port-au-Prince Scott E. Smith 1979-1981 Head of Project Development Office, USAID, Port-au-Prince Henry L. Kimelman 1980-1981 Ambassador, Haiti David R. Adams 1981-1984 Mission Director, USAID, Haiti Clayton E. McManaway, Jr. 1983-1986 Ambassador, Haiti Jon G. -

![HAITI - Boundaries - Département Sud [07] 8 March 2010](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9210/haiti-boundaries-d%C3%A9partement-sud-07-8-march-2010-489210.webp)

HAITI - Boundaries - Département Sud [07] 8 March 2010

HAITI - Boundaries - Département Sud [07] 8 March 2010 0 50 100 km [9] [3] [4] 152-01 [5] 152-05 Pointe a Raquette [6] 152-02 152-03 OUEST [1] 151-04 [1] [8] [10] 151-02 151-03 [2] 152-04 Anse-a-Galet 151-01 151-05 811-09 812-01 813-01 812-04 811-08 Abricots Bonbon 834-06 822-04 811-07 811-04 812-03 812-02 Jeremie 811-01 832-04 822-05 814-01 811-05 831-03 1032-01 Roseaux Grand Boucan Dame-Marie 1032-02 815-01 832-01 832-03 822-03 831-01 Corail 834-01 822-01 Chambellan GRANDE ANSE [8] 831-02 834-02 833-02 1031-05 822-02 811-02 1021-01 1022-02 1022-01 815-02 811-06 821-01 832-02 Baraderes Pestel 1031-01 Petit Trou de Nippes 1021-02 1021-03 Anse-d'Hainault 834-03 1012-04 833-03 1031-04 1024-01 1012-01 1012-03 821-03 834-04 1031-03 Anse-a-Veau Petite Riviere de Nippes 122-03 814-02 1025-02 821-02 811-03 Beaumont 1012-02 821-04 1025-01 Moron 833-01 834-05 1031-02 Plaisance du Sud Arnaud NIPPES [10] 122-02 823-01 814-03 1022-03 1024-03 1024-02 1011-01 122-01 733-05 1014-01 Paillant 1025-03 1023-03 Les Irois 1013-04 1014-02 733-04 1023-04 1013-01 122-11 823-02 715-03 715-02 1013-02 Petit-Goave 823-03 752-03 752-02 L'Asile Fond Des Negres 1013-03 1011-04 122-05 122-07 714-02 Maniche Miragoane 122-04 753-02 Les Anglais 751-01 1023-02 1023-01 731-08 Cavaillon 733-03 1011-02 Camp Perrin 731-10 122-06 122-10 753-03 715-01 Chardonnieres 712-04 714-03 733-02 731-02 Tiburon 732-08 732-07 753-04 752-01 742-02 731-05 122-08 753-01 711-03 711-05 731-06 713-03 714-01 732-05 732-01 731-03 1011-03 122-09 Port-a-Piment 731-09 751-03 St.