Bottom-Up Development in Haiti

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

USAID/OFDA Haiti Earthquake Program Maps 6/4/2010

EARTHQUAKE-AFFECTED AREAS AND POPULATION MOVEMENT IN HAITI CUBAEARTHQUAKE INTENSITY 73° W 72° W The Modified Mercalli (MMI) Intensity Scale* NORTHWESTNORTHWEST Palmiste N N 20° NORTHWEST 20° ESTIMATED MMI INTENSITY Port-de-Paix 45,862 Saint Louis Du Nord LIGHT SEVERE 4 8 Anse-a-foleur NORTH Jean Rabel 13,531 Monte Cristi 5 MODERATE 9 VIOLENT Le Borgne NORTHWESTNORTHWEST Cap-Haitien NORTHEAST 6 STRONG 10^ EXTREME Bassin-bleu Port-margot Quartier 8,500 Limbe Marin Caracol 7 VERY STRONG Baie-de-Henne Pilate Acul Plaine Phaeton Anse Rouge Gros Morne Limonade Fort-Liberte *MMI is a measure of ground shaking and is different Du Nord Du Nord from overall earthquake magnitude as measured Plaisance Trou-du-nord NORTHNORTH Milot Ferrier by the Richter Scale. Terre-neuve Sainte Suzanne ^Area shown on map may fall within MMI 9 Dondon Grande Riviera Quanaminthe classification, but constitute the areas of heaviest Dajabon ARTIBONITE Du Nord Perches shaking based on USGS data. Marmelade 162,509 Gonaives Bahon Source: USGS/PAGER Alert Version: 8 Ennery Saint-raphael NORTHEASTNORTHEAST HAITI EARTHQUAKE Vallieres Ranguitte Saint Michel Mont Organise 230,000 killed ARTIBONITEARTIBONITE De L'attalaye Pignon 196,595 injured La Victoire POPULATION MOVEMENT * 1,200,000 to 1,290,000 displaced CENTER Source: OCHA 02.22.10 Dessalines Cerca 3,000,000 affected Grande-Saline 90,997Carvajal * Population movements indicated include only Maissade Cerca-la-source individuals utilizing GoH-provided transportation *All figures are approximate. Commune Petite-riviere- Hinche and do not include people leaving Port-au-Prince population figures are as of 2003. de-l'artibonite utilizing private means of transport. -

Assessment of Haitian Coffee Value Chain

Assessment of Haitian Coffee Value Chain Fernando Rodríguez, Nora Patricia Castañeda, Mark Lundy A participatory assessment of coffee chain actors in southern Haiti assessment Copyright © 2011 Catholic Relief Services Catholic Relief Services 228 West Lexington Street Baltimore, MD 21201-3413 USA Cover photo: Coffee plants in Haiti. CRS staff. Download this and other CRS publications at www.crsprogramquality.org Assessment of HAitiAn Coffee VAlue Chain A participatory assessment of coffee chain actors in southern Haiti July 12–August 30, 2010 Table of Contents Abbreviations and Acronyms . iii 1 Executive Summary. IV 2 Introduction. 1 3 Relevance of Coffee in Haiti. 1 4 Markets . 4 5 Coffee Chain Analysis. 5 6 Constraints Analyses. 17 7 Recommendations . 19 Glossary . 22 References . 24 Annexes . 25 Annex 1: Problem Tree. 25 Annex 2: Production Solution Tree. 26 Annex 3: Postharvest Solution Tree . 27 Annex 4: Marketing Solution Tree. 28 Annex 5: Conclusions Obtained with Workshops Participants. 29 Figures Figure 1: Agricultural sector participation in total GDP. 1 Figure 2: Coffee production. 3 Figure 3: Haitian coffee exports. 4 Figure 4: Coffee chain in southern Haiti. 6 Figure 5: Potential high-quality coffee municipalities in Haiti. 9 Tables Table 1: Summary of chain constraints and strategic objectives to address them. IV Table 2: Principal coffee growing areas and their potential to produce quality coffee. 2 Table 3: Grassroots organizations and exporting regional networks. 3 Table 4: Land distribution by plot size . 10 Table 5: Coffee crop area per department in 1995 . 10 Table 6: Organizations in potential high-quality coffee municipalities. 12 Table 7: Current and potential washed coffee production in the region . -

")Un ")Un ")Un ")Un ")Un ")Un ")Un ")Un ")Un ")Un

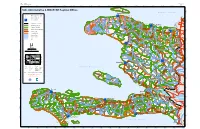

HAITI: 1:900,000 Map No: ADM 012 Stock No: M9K0ADMV0712HAT22R Edition: 2 30' 74°20'0"W 74°10'0"W 74°0'0"W 73°50'0"W 73°40'0"W 73°30'0"W 73°20'0"W 73°10'0"W 73°0'0"W 72°50'0"W 72°40'0"W 72°30'0"W 72°20'0"W 72°10'0"W 72°0'0"W 71°50'0"W 71°40'0"W N o r d O u e s t N " 0 Haiti: Administrative & MINUSTAH Regional Offices ' 0 La Tortue ! ° 0 N 2 " (! 0 ' A t l a n t i c O c e a n 0 ° 0 2 Port de Paix \ Saint Louis du Nord !( BED & Department Capital UN ! )"(!\ (! Paroli !(! Commune Capital (!! ! ! Chansolme (! ! Anse-a-Foleur N ( " Regional Offices 0 UN Le Borgne ' 0 " ! 5 ) ! ° N Jean Rabel " ! (! ( 9 1 0 ' 0 5 ° Mole St Nicolas Bas Limbe 9 International Boundary 1 (!! N o r d O u e s t (!! (!! Department Boundary Bassin Bleu UN Cap Haitian Port Margot!! )"!\ Commune Boundary ( ( Quartier Morin ! N Commune Section Boundary Limbe(! ! ! Fort Liberte " (! Caracol 0 (! ' ! Plaine 0 Bombardopolis ! ! 4 Pilate ° N (! ! ! " ! ( UN ( ! ! Acul du Nord du Nord (! 9 1 0 Primary Road Terrier Rouge ' (! (! \ Baie de Henne Gros Morne Limonade 0 )"(! ! 4 ! ° (! (! 9 Palo Blanco 1 Secondary Road Anse Rouge N o r d ! ! ! Grande ! (! (! (! ! Riviere (! Ferrier ! Milot (! Trou du Nord Perennial River ! (! ! du Nord (! La Branle (!Plaisance ! !! Terre Neuve (! ( Intermittent River Sainte Suzanne (!! Los Arroyos Perches Ouanaminte (!! N Lake ! Dondon ! " 0 (! (! ' ! 0 (! 3 ° N " Marmelade 9 1 0 ! ' 0 Ernnery (!Santiag o \ 3 ! (! ° (! ! Bahon N o r d E s t de la Cruz 9 (! 1 ! LOMA DE UN Gonaives Capotille(! )" ! Vallieres!! CABRERA (!\ (! Saint Raphael ( \ ! Mont -

Earthquake-Affected Areas and Population Movement in Haiti

USG HUMANITARIAN ASSISTANCE TO HAITI FOR THE EARTHQUAKE CUBA KEY 73° W 72° W NORTHWEST Palmiste N N 20°USAID/OFDA USAID/FFP USAID/OTI 20° Port-de-Paix USAID/DR USAID/HAITI DoD Saint Louis Du Nord ECONOMIC RECOVERY AND Anse-a-foleur C MARKET SYSTEMS Jean Rabel Le Borgne Monte Cristi K EMERGENCY RESPONSE ACTIVITIES NORTHWEST Port-margot Cap-Haitien HEALTH Bassin-bleu ç Quartier Limbe HUMANITARIAN AIR SERVICE Marin Caracol b Baie-de-Henne Pilate Acul HUMANITARIAN COORDINATION Gros Morne Plaine Phaeton Anse Rouge Du Nord Du Nord Limonade Fort-Liberte B AND INFORMATION MANAGEMENT Plaisance Trou-du-nord NORNORTHTH Milot Ferrier INFRASTRUCTURE REHABILITATION Terre-neuve Sainte Suzanne o Dondon Grande Riviera Quanaminthe Dajabon LOGISTICS AND RELIEF COMMODITIES Du Nord Perches a Marmelade Gonaives Bahon NUTRITION Ennery Saint-raphael NORTHEAST F Vallieres G PROTECTION Ranguitte Affected Areas Saint Michel Mont Organise I SHELTER AND SETTLEMENTS ARARTIBONITETIBONITE De L'attalaye Pignon DoD USAID/DR La Victoire TITLE II EMERGENCY FOOD a a FH I ç USAR ; J Ga Dessalines Cerca ∑ TRANSITION INITIATIVE F HHS WFP ro Grande-Saline Carvajal ç b a m Maissade Cerca-la-source ; URBAN SEARCH AND RESCUE M Implementing Partners K WHO ia Petite-riviere- Hinche ç m de-l'artibonite WATER, SANITATION, AND HYGIENE i, Saint-Marc J F 02. .10 InterAction B WFP and NGOs L 10 to IOM Chemonics Thomassique REPUBLIC DOMINICAN a Po Verrettes ∑ r N t- CENTER N 19° OCHA B DAI au 19° ∑ -P r Peace Corps Internews in B ∑ ce BaptisteEliasWEST Pina RI Jç USAID/DR ç Belladere Mirebalais -

Cholera Treatment Facility Distribution for Haiti

municipalities listed above. listed municipalities H C A D / / O D F I **Box excludes facilities in the in facilities excludes **Box D A du Sud du A S Ile a Vache a Ile Ile a Vache a Ile Anse a pitres a Anse Saint Jean Saint U DOMINICAN REPUBLIC municipalities. Port-au-Prince Port-Salut Operational CTFs : 11 : CTFs Operational Delmas, Gressier, Gressier, Delmas, Pétion- Ville, and and Ville, G Operational CTFs : 13 : CTFs Operational E T I O *Box includes facilities in Carrefour, in facilities includes *Box N G SOUTHEAST U R SOUTH Arniquet A N P Torbeck O H I I T C A I Cote de Fer de Cote N M Bainet R F O Banane Roche A Bateau A Roche Grand Gosier Grand Les Cayes Les Coteaux l *# ! Jacmel *# Chantal T S A E H T U O SOUTHEAST S SOUTHEAST l Port à Piment à Port ! # Sud du Louis Saint Marigot * Jacmel *# Bodarie Belle Anse Belle Fond des Blancs des Fond # Chardonnières # * Aquin H T U O S SOUTH * SOUTH *# Cayes *# *# Anglais Les *# Jacmel de Vallée La Perrin *# Cahouane La Cavaillon Mapou *# Tiburon Marbial Camp Vieux Bourg D'Aquin Bourg Vieux Seguin *# Fond des Negres des Fond du Sud du Maniche Saint Michel Saint Trouin L’Asile Les Irois Les Vialet NIPPES S E P P I NIPPES N Fond Verrettes Fond WEST T S E WEST W St Barthélemy St *# *#*# Kenscoff # *##**# l Grand Goave #Grand #* * *#* ! Petit Goave Petit Beaumont # Miragoane * Baradères Sources Chaudes Sources Malpasse d'Hainault GRAND-ANSE E S N A - D N A R GRAND-ANSE G Petite Riviere de Nippes de Riviere Petite Ile Picoulet Ile Petion-Ville Ile Corny Ile Anse Ganthier Anse-a-Veau Pestel -

Community Radios April17

Haiti: Communication with communities - Mapping of community radio stations (Avr. 2017) La Tortue Bwa Kayiman 95.9 Port De Paix Zèb Tènite Saint Louis Kòn Lanbi 95.5 du Nord Anse A Foleur Jean Rabel Chamsolme Vwa kominotè Janrabèl Borgne Quartier Morin Bas Limbe Cap Haitien Vwa Liberasyon Mole Saint Nicolas Nord Ouest Bassin Bleu Pèp la 99.9 Port Margot Gros Morne Fransik 97.9 Pilate Plaine Baie de Henne Vwa Gwo Mòn 95.5 Eko 94.1 du Nord Caracol Bombardopolis Limbe Vestar FM Anse Rouge Milot Limonade Acul du Nord Terrier Rouge Ferrier Solidarité Terre Neuve Plaisance Natif natal Nord Trou du Nord Fort Liberte Zèb Ginen 97.7 Radyo Kominotè Sainte Suzanne Nòdès 92.3 Marmelade Gonaives Ouanaminthe Trans Ennery Dondon Nord Est Massacre Unité Bahon Valliere Capotille St. Raphael Tropicale 89.9 Capotille FM Ranquitte L'Estere La Victoire Mont Organise Saint-Michel de l'Attal Mombin Legend Desdunes Inite Sen Michel Pignon Crochu Carice Artibonite Tèt Ansanm 99.1 Grande Saline Communes ayant au moins Cerca Carvajal Dessalines/Marchandes une radio communautaire Maissade Radyo kominotè Mayisad Cerca La Source Communes sans Hinche radio communautaire Saint-Marc Vwa Peyizan 93.9 Imperial Petite Riviere de l'Artibonite Thomassique Cosmos Centre Xplosion Verrettes Thomonde Chandèl FM 106.1 Makandal 101.5 Xaragua 89.5 Grand’Anse 95.9 Boucan Carre Power Mix 97.5 Pointe A Raquette La Chapelle Kalfou 96.5 Arcahaie Lascahobas Tropette Evangelique 94.3 Belladere Orbite 100.7 Saut d'Eau Tet Ansanm 105.9 Anse A Galet Mirebalais CND 103.5 Cabaret Tera 89.9 -

WATER RESOURCES ASSESSMENT of HAITI August 1999

WATER RESOURCES ASSESSMENT OF HAITI August 1999 Haiti Dominican Republic US Army Corps of Engineers Mobile District and Topographic Engineering Center Water Resources Assessment of Haiti Executive Summary Haiti is one of the most densely populated countries in the world and one of the poorest in the Western Hemisphere. The population has already outstripped domestic food production, and it is estimated that the population will be 8 million by the year 2000. One-third of the population lives in the Département de l’Ouest where Port-au-Prince is located. Heavy migration from rural areas to towns and cities occurring over the past decade has adversely affected the distribution of the water supply. Access to water and sanitation facilities is inadequate, contributing to poor living conditions, disease, and a high mortality rate. In 1990 only 39 percent of the 5.9 million residents had adequate access to water and only 24 percent to sanitation. The lack of potable water for basic human needs is one of the most critical problems in the country. Given the rainfall and abundant water resources, there is adequate water to meet the water demands, but proper management to develop and maintain the water supply requirements is lacking. However, the water supply sector is undergoing complete transformation. Although currently there is no comprehensive water policy, progress is being made towards establishing a national water resources management policy. Numerous agencies and non-government organizations (NGO’s) are working to provide water, many of which conduct their missions with little or no coordination with other agencies, which creates duplication of work and inefficient use of resources. -

HAITI: the Orphan Chronicles

Occasional Paper N° 23 Bryant C. Freeman, Ph.D. Series Editor Michelle Etnire HAITI: The Orphan Chronicles Institute of Haitian Studies University of Kansas 2000 University of Kansas Institute of Haitian Studies Occasional Papers Bryant C. Freeman, Ph.D. - Series Editor N° 1 - Konstitisyon Repiblik Ayiti, 29 mas 1987. 1994. Pp. vi-106. Haitian-language version (official orthography) of the present Constitution, as translated by Paul Dejean with the collaboration of Yves Dejean. Introduction in English. $12.00 N° 2 - Toussaint's Constitution (1801), with Introduction. 1994. Pp. ix-20. In French. Introduction (in English) by Series editor places Constitution in its historic context and analyzes salient features. $5.00 N° 3 - Bryant C. Freeman, Selected Critical Bibliography of English-Language Books on Haiti. 1999 (Updated). Pp. 24. Contains 177 entries, with brief description of each; special list of "Top Ten." Introduction and text in English. Updated periodically. $5.00 N° 4 - Strategy of Aristide Government for Social and Economic Reconstruction (August 1994). 1994. Pp. iv-9. Official document setting forth recovery plan for Haiti. Introduction and text in English. $4.00 N° 5 - Robert Earl Maguire, Bottom-Up Development in Haiti. 1995. Pp. iv-63. Keynote: develop people rather than things, with case study as carried out in Le Borgne. Introduction and text in English. $8.00 N° 6 - Robert Earl Maguire, Devlopman Ki Soti nan Baz nan Peyi Dayiti. 1995. Pp. v-71. Haitian- language version of N° 5,.in Pressoir-Faublas orthography. Introduction in English. $8.00 N° 7 - Samuel G. Perkins, "On the Margin of Vesuvius": Sketches of St Domingo, 1785-1793. -

American Eel (Anguilla Rostrata) Stock Status in Haiti

American Eel (Anguilla rostrata) Stock status in Haiti © Eladio F. Anderson JEAN Agroforestery and Environmental sciences Major fishing regions of American Eel in Haiti • North: Cap-Haitien, Bas-Limbé, Port Margot, Borgne, Limonade, Camp Louise, Labadee. • North-East: Caracol • Artibonite: Saint-Marc • South-East: Jacmel • Grade-Anse: Jérémie, commune des Roseaux. • Nippes: Kawouk, Petite-Riviere de Nippes. Timing and average length reported for glass-stage American eel 1. Memorandum August 12th, 2019: Ministry of Agriculture, Naturals Ressources and rural Developpement (MARNDR) 1.1 Timing: September 2nd, to April 15th . 1.2 Quota is set : 6,400 kilograms per exporter. NB: Haiti export glass-stage American eel at an average length 48mm. Wang and Tzeng 2000 National eel stock status État du stock national d'anguilles However, according to MARNDR officials: • Haiti has an export capacity of 800 metric tonnes per year. Existing monitoring programs and methods Programmes et méthodes de surveillance existants • There’s no monitoring programs and methods data collection presently to determine the status of American eel in Haiti Overview of fisheries and associated management 1.1 Source of income: $1 to 5us/Gram One person could collect 1000G./3days 1.2 Currently no biological conservation plan undertake Bibliography • https://ayibopost.com/la-peche-aux-anguilles-rapporte-de-largent-mais-tue-des-jeunes-a-jeremie/ • https://lenouvelliste.com/article/205845/de-nouvelles-mesures-pour-regulariser-lexploitation-et-lexportation-des-anguilles • https://lenouvelliste.com/article/220991/la-peche-au-zangui-anguilles-une-manne-maritime-pour-les-habitants-de-kawouk • https://koukouyayiti.wordpress.com/2018/12/17/la-filiere-de-languille-la-nouvelle-poule-aux-oeufs-dor/ • Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission, May 2012, American Eel Benchmark Stock Assessment. -

An Update to Haiti's Administrative Organization

HAITI ---AN UPDATE TO ITS ADMINISTRATIVE/POSTAL ORGANIZATION By Wally Deltoro In 2007, I came across an interesting website devoted to information concerning the administrative divisions of the countries of the world. My curiosity led me to the section pertaining to HAITI. The country section contained much information that directly or indirectly is pertinent to the knowledge we as collectors of Haiti philately should be familiar with. Specifically several pieces of information were of philatelic interest: 1- Haiti is no longer divided into 9 departments but rather 10 departments 2- The new department, NIPPES, was created in 2003 3- A listing of all of Haiti’s Arrondissements was provided that included the first 2 digits of the postal code. Overall, the information provided I found it to be interesting and useful. It certainly would be for those of us interested in town cancellations. Thus, in my desire to share it with our membership, I requested and obtained approval to publish information from the Haiti pages from the producer of the web site, Mr. Gwillim Law from Chapel Hill, NC, USA. His web site, Administrative Divisions of Countries ("Statoids") (http://www.statoids.com), provides similar information on all countries of the world. *** The Postal Codes of Haiti Haiti uses four-digit postal codes, always prefixed with "HT". The first digit represents the department; the first two, the arrondissement; the first three, the commune. The Departments of Haiti The eastern half of the Grand' Anse department was evidently split off to form Nippes department. The capital is Miragoâne. The electoral decree of 2005-02-03 states that the department of Nippes was created by a law of 2003-09-04. -

USAID/OFDA Haiti Earthquake Program Maps 6/4/2010

EARTHQUAKE-AFFECTED AREAS AND POPULATION MOVEMENT IN HAITI CUBAEARTHQUAKE INTENSITY 73° W 72° W The Modified Mercalli (MMI) Intensity Scale* NORTHWESTNORTHWEST Palmiste N N 20° NORTHWEST 20° ESTIMATED MMI INTENSITY Port-de-Paix 45,862 Saint Louis Du Nord LIGHT SEVERE 4 8 Anse-a-foleur NORTH Jean Rabel 13,531 Monte Cristi 5 MODERATE 9 VIOLENT Le Borgne NORTHWESTNORTHWEST Cap-Haitien NORTHEAST 6 STRONG 10^ EXTREME Bassin-bleu Port-margot Quartier 8,500 Limbe Marin Caracol 7 VERY STRONG Baie-de-Henne Pilate Acul Plaine Phaeton Anse Rouge Gros Morne Limonade Fort-Liberte *MMI is a measure of ground shaking and is different Du Nord Du Nord from overall earthquake magnitude as measured Plaisance Trou-du-nord NORTHNORTH Milot Ferrier by the Richter Scale. Terre-neuve Sainte Suzanne ^Area shown on map may fall within MMI 9 Dondon Grande Riviera Quanaminthe classification, but constitute the areas of heaviest Dajabon ARTIBONITE Du Nord Perches shaking based on USGS data. Marmelade 162,509 Gonaives Bahon Source: USGS/PAGER Alert Version: 8 Ennery Saint-raphael NORTHEASTNORTHEAST HAITI EARTHQUAKE Vallieres Ranguitte Saint Michel Mont Organise 230,000 killed ARTIBONITEARTIBONITE De L'attalaye Pignon 196,595 injured La Victoire POPULATION MOVEMENT * 1,200,000 to 1,290,000 displaced CENTER Source: OCHA 02.22.10 Dessalines Cerca 3,000,000 affected Grande-Saline 90,997Carvajal * Population movements indicated include only Maissade Cerca-la-source individuals utilizing GoH-provided transportation *All figures are approximate. Commune Petite-riviere- Hinche and do not include people leaving Port-au-Prince population figures are as of 2003. de-l'artibonite utilizing private means of transport. -

Livelihood Profiles in Haiti September 2005 USAID FEWS

Livelihood Profiles in Haiti September 2005 CUBA Voute I Eglise ! 0 2550 6 Aux Plains ! Kilometers Saint Louis du Nord ! Jean Rabel ! NORD-OUEST Beau Champ Mole-Saint-Nicolas ! ! 5 Cap-Haitien (!! 1 Limbe Bombardopolis ! ! Baie-de-Henne Cros Morne !( 2 ! !(! Terrier Rouge ! ! La Plateforme Grande-Riviere !( Plaisance ! 2 du-Nord ! Quanaminthe !(! 7 3 NORD 1 ! Gonaives !( NORD-EST ! Saint-Michel Mont Organise de-lAtalaye ! Pignon 7 ! 2 USAID Dessalines ! ! Cerca Carvajal ARTIBONITE Hinche Petite-Riviere ! Saint-Marc ! !( ! de-LArtibonite Thomassique (! ! ! CENTRE FEWS NET Verrettes Bouli ! La Cayenne Grande Place 4 ! ! ! La Chapelle Etroits 6 1 ! Mirebalais Lascahobas ! ! Nan-Mangot Arcahaie 5 ! ! 3 Seringue Jeremie ! 6 ! (! Roseaux ! Grande Cayemite OUEST Cap Dame-Marie ! Corail ! In collaboration with: ! Port-Au-Prince Pestel ! 2 DOMINICAN ! Anse-a-Veau ^ Anse-DHainault (! ! GRANDE-ANSE ! (! ! ! 6 ! Miragoane 6Henry Petion-Ville Baraderes ! Sources Chaudes Petit-Goave 2 8 NIPPES ! (!! 6 REPUBLIC 5 3 Carrefour Moussignac Lasile ! Trouin Marceline ! ! 3 ! ! Les Anglais Cavaillon Platon Besace Coordination Nationale de la Tiburon ! ! Aquin ! 5 SUD ! Boucan Belier SUD-EST ! Belle-Anse ! 6 ! ! Port-a-Piment 6 1 (!! Jacmel ! ! Thiote Coteaux (!! ! 6 ! 5 Marigot Sécurité Alimentaire du Les Cayes Laborieux 6 2 Bainet Saint-Jean Ile a Vache ! ! ! Port Salut Gouvernement d’Haïti (CNSA) United States Agency for Livelihood Zone International Development/Haiti 1 Dry Agro-pastoral Zone (USAID/Haiti) 2 Plains under Monoculture Zone CARE 3 Humid