HAITI: the Orphan Chronicles

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

USAID/OFDA Haiti Earthquake Program Maps 6/4/2010

EARTHQUAKE-AFFECTED AREAS AND POPULATION MOVEMENT IN HAITI CUBAEARTHQUAKE INTENSITY 73° W 72° W The Modified Mercalli (MMI) Intensity Scale* NORTHWESTNORTHWEST Palmiste N N 20° NORTHWEST 20° ESTIMATED MMI INTENSITY Port-de-Paix 45,862 Saint Louis Du Nord LIGHT SEVERE 4 8 Anse-a-foleur NORTH Jean Rabel 13,531 Monte Cristi 5 MODERATE 9 VIOLENT Le Borgne NORTHWESTNORTHWEST Cap-Haitien NORTHEAST 6 STRONG 10^ EXTREME Bassin-bleu Port-margot Quartier 8,500 Limbe Marin Caracol 7 VERY STRONG Baie-de-Henne Pilate Acul Plaine Phaeton Anse Rouge Gros Morne Limonade Fort-Liberte *MMI is a measure of ground shaking and is different Du Nord Du Nord from overall earthquake magnitude as measured Plaisance Trou-du-nord NORTHNORTH Milot Ferrier by the Richter Scale. Terre-neuve Sainte Suzanne ^Area shown on map may fall within MMI 9 Dondon Grande Riviera Quanaminthe classification, but constitute the areas of heaviest Dajabon ARTIBONITE Du Nord Perches shaking based on USGS data. Marmelade 162,509 Gonaives Bahon Source: USGS/PAGER Alert Version: 8 Ennery Saint-raphael NORTHEASTNORTHEAST HAITI EARTHQUAKE Vallieres Ranguitte Saint Michel Mont Organise 230,000 killed ARTIBONITEARTIBONITE De L'attalaye Pignon 196,595 injured La Victoire POPULATION MOVEMENT * 1,200,000 to 1,290,000 displaced CENTER Source: OCHA 02.22.10 Dessalines Cerca 3,000,000 affected Grande-Saline 90,997Carvajal * Population movements indicated include only Maissade Cerca-la-source individuals utilizing GoH-provided transportation *All figures are approximate. Commune Petite-riviere- Hinche and do not include people leaving Port-au-Prince population figures are as of 2003. de-l'artibonite utilizing private means of transport. -

Bottom-Up Development in Haiti

Occasional Paper N° 5 Robert Earl Maguire Bottom-Up Development in Haiti Institute of Haitian Studies University of Kansas Occasional Paper N° 5 Bryant C. Freeman, Ph.D. General Editor Robert Earl Maguire Bottom-Up Development in Haiti Institute of Haitian Studies University of Kansas 1995 University of Kansas Institute of Haitian Studies Occasional Papers Bryant C. Freeman, Ph.D. - General Editor No 1 - Konstitisyon Repiblik Ayiti, 29 mas 1987. September 1994. Pp. vi-106. Haitian-language version (official orthography) of the present Constitution, as translated by Paul Déjean with the collaboration of Yves Déjean. Introduction in English. No 2 - Toussaint's Constitution (1801), with Introduction. October 1994. Pp. ix-20. In French. Introduction (in English) places Constitution in its historic context and analyzes salient features. No 3 - Bryant C. Freeman, Selected Critical Bibliography of English-Language Books on Haiti. February 1995 (Updated). Pp. 21. More than 150 entries, with brief description of each; special list of "Top Ten." Introduction and text in English. Updated periodically. No 4 - Strategy of Aristide Government for Social and Economic Reconstruction (August 1994). December 1994. Pp. iv-9. Official document setting forth recovery plan for Haiti. Introduction and text in English. No 5 - Robert Earl Maguire, Bottom-Up Development in Haiti. January 1995. Pp. iv-63. Keynote: develop people rather than things, with case study as carried out in Le Borgne. Introduction and text in English. N° 6 - Robert Earl Maguire, Devlopman Ki Soti nan Baz nan Peyi Dayiti. February 1995. Pp. v-71. Haitian-language version of N° 5, in Pressoir-Faublas orthography. -

Focus on Haiti

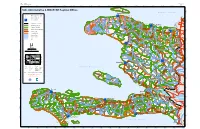

FOCUS ON HAITI CUBA 74o 73o 72o ÎLE DE LA TORTUE Palmiste ATLANTIC OCEAN 20o Canal de la Tortue 20o HAITI Pointe Jean-Rabel Port-de-Paix St. Louis de Nord International boundary Jean-Rabel Anse-à-Foleur Le Borgne Departmental boundary Monte Cap Saint-Nicolas Môle St.-Nicolas National capital Bassin-Bleu Baie de Criste NORD - OUEST Port-Margot Cap-Haïtien Mancenille Departmental seat Plaine Quartier Limbé du Nord Caracol Fort- Town, village Cap-à-Foux Bombardopolis Morin Liberté Baie de Henne Gros-Morne Pilate Acul Phaëton Main road Anse-Rouge du Nord Limonade Baie Plaisance Milot Trou-du-Nord Secondary road de Grande Terre-Neuve NORD Ferrier Dajabón Henne Pointe Grande Rivière du Nord Sainte Airport Suzanne Ouanaminthe Marmelade Dondon Perches Ennery Bahon NORD - EST Gonaïves Vallières 0 10 20 30 40 km Baie de Ranquitte la Tortue ARTIBONITE Saint- Raphaël Mont-Organisé 0 5 10 15 20 25 mi Pointe de la Grande-Pierre Saint Michel Baie de de l'Attalaye Pignon La Victoire Golfe de la Gonâve Grand-Pierre Cerca Carvajal Grande-Saline Dessalines Cerca-la-Source Petite-Rivière- Maïssade de-l'Artibonite Hinche Saint-Marc Thomassique Verrettes HAITI CENTRE Thomonde 19o Canal de 19o Saint-Marc DOMINICAN REPUBLIC Pointe Pointe de La Chapelle Ouest Montrouis Belladère Magasin Lac de ÎLE DE Mirebalais Péligre LA GONÂVE Lascahobas Pointe-à-Raquette Arcahaie Saut-d'Eau Baptiste Duvalierville Savenette Abricots Pointe Cornillon Jérémie ÎLES CAYÉMITES Fantasque Trou PRESQU'ÎLE Thomazeau PORT- É Bonbon DES BARADÈRES Canal de ta AU- Croix des ng Moron S Dame-Marie la Gonâve a Roseaux PRINCE Bouquets u Corail Gressier m Chambellan Petit Trou de Nippes â Pestel tr Carrefour Ganthier e Source Chaude Baradères Anse-à-Veau Pétion-Ville Anse d'Hainault Léogâne Fond Parisien Jimani GRANDE - ANSE NIPPES Petite Rivières Kenscoff de Nippes Miragoâne Petit-Goâve Les Irois Grand-Goâve OUEST Fonds-Verrettes L'Asile Trouin La Cahouane Maniche Camp-Perrin St. -

Assessment of Haitian Coffee Value Chain

Assessment of Haitian Coffee Value Chain Fernando Rodríguez, Nora Patricia Castañeda, Mark Lundy A participatory assessment of coffee chain actors in southern Haiti assessment Copyright © 2011 Catholic Relief Services Catholic Relief Services 228 West Lexington Street Baltimore, MD 21201-3413 USA Cover photo: Coffee plants in Haiti. CRS staff. Download this and other CRS publications at www.crsprogramquality.org Assessment of HAitiAn Coffee VAlue Chain A participatory assessment of coffee chain actors in southern Haiti July 12–August 30, 2010 Table of Contents Abbreviations and Acronyms . iii 1 Executive Summary. IV 2 Introduction. 1 3 Relevance of Coffee in Haiti. 1 4 Markets . 4 5 Coffee Chain Analysis. 5 6 Constraints Analyses. 17 7 Recommendations . 19 Glossary . 22 References . 24 Annexes . 25 Annex 1: Problem Tree. 25 Annex 2: Production Solution Tree. 26 Annex 3: Postharvest Solution Tree . 27 Annex 4: Marketing Solution Tree. 28 Annex 5: Conclusions Obtained with Workshops Participants. 29 Figures Figure 1: Agricultural sector participation in total GDP. 1 Figure 2: Coffee production. 3 Figure 3: Haitian coffee exports. 4 Figure 4: Coffee chain in southern Haiti. 6 Figure 5: Potential high-quality coffee municipalities in Haiti. 9 Tables Table 1: Summary of chain constraints and strategic objectives to address them. IV Table 2: Principal coffee growing areas and their potential to produce quality coffee. 2 Table 3: Grassroots organizations and exporting regional networks. 3 Table 4: Land distribution by plot size . 10 Table 5: Coffee crop area per department in 1995 . 10 Table 6: Organizations in potential high-quality coffee municipalities. 12 Table 7: Current and potential washed coffee production in the region . -

")Un ")Un ")Un ")Un ")Un ")Un ")Un ")Un ")Un ")Un

HAITI: 1:900,000 Map No: ADM 012 Stock No: M9K0ADMV0712HAT22R Edition: 2 30' 74°20'0"W 74°10'0"W 74°0'0"W 73°50'0"W 73°40'0"W 73°30'0"W 73°20'0"W 73°10'0"W 73°0'0"W 72°50'0"W 72°40'0"W 72°30'0"W 72°20'0"W 72°10'0"W 72°0'0"W 71°50'0"W 71°40'0"W N o r d O u e s t N " 0 Haiti: Administrative & MINUSTAH Regional Offices ' 0 La Tortue ! ° 0 N 2 " (! 0 ' A t l a n t i c O c e a n 0 ° 0 2 Port de Paix \ Saint Louis du Nord !( BED & Department Capital UN ! )"(!\ (! Paroli !(! Commune Capital (!! ! ! Chansolme (! ! Anse-a-Foleur N ( " Regional Offices 0 UN Le Borgne ' 0 " ! 5 ) ! ° N Jean Rabel " ! (! ( 9 1 0 ' 0 5 ° Mole St Nicolas Bas Limbe 9 International Boundary 1 (!! N o r d O u e s t (!! (!! Department Boundary Bassin Bleu UN Cap Haitian Port Margot!! )"!\ Commune Boundary ( ( Quartier Morin ! N Commune Section Boundary Limbe(! ! ! Fort Liberte " (! Caracol 0 (! ' ! Plaine 0 Bombardopolis ! ! 4 Pilate ° N (! ! ! " ! ( UN ( ! ! Acul du Nord du Nord (! 9 1 0 Primary Road Terrier Rouge ' (! (! \ Baie de Henne Gros Morne Limonade 0 )"(! ! 4 ! ° (! (! 9 Palo Blanco 1 Secondary Road Anse Rouge N o r d ! ! ! Grande ! (! (! (! ! Riviere (! Ferrier ! Milot (! Trou du Nord Perennial River ! (! ! du Nord (! La Branle (!Plaisance ! !! Terre Neuve (! ( Intermittent River Sainte Suzanne (!! Los Arroyos Perches Ouanaminte (!! N Lake ! Dondon ! " 0 (! (! ' ! 0 (! 3 ° N " Marmelade 9 1 0 ! ' 0 Ernnery (!Santiag o \ 3 ! (! ° (! ! Bahon N o r d E s t de la Cruz 9 (! 1 ! LOMA DE UN Gonaives Capotille(! )" ! Vallieres!! CABRERA (!\ (! Saint Raphael ( \ ! Mont -

Masterlist Abri Provisoire

MASTERLIST ABRI PROVISOIRE SOMMAIRE # DEPARTEMENT # ABRIS PAGES 1 Artibonite 76 1 2 Centre 60 8 3 Grande-Anse 180 13 4 NiPPes 117 29 5 Nord 248 40 6 Nord-Est 38 63 7 Nord-Ouest 177 66 8 Ouest 212 82 9 Sud 182 101 10 Sud-Est 187 118 TOTAL 1477 COORDONEE GPS Capacité # Departement Commune Section Site Adresse Maximale Remarques Dernière mise à jour Latitude Longitude théorique Besoin de éParation au nivau du corPs 1 Artibonite Anse Rouge Centre Ville Ecole Nationale de Anse Rouge 13, RUE RAVINE 19.6352 -73.0539 0 mai 2017/ Par OIM du batiment et de la toiture 2 Artibonite Anse Rouge Ecole Eben-Ezer n/a n/a n/a 0 Besoin en eau et assainissement n/a 3 Artibonite Anse Rouge Centre Sociale de Anse Rouge n/a n/a n/a 0 Besoin en eau et assainissement n/a besoin d'aménagement de sanitaires suPlémentaire, travaux de finition 4 Artibonite Anse Rouge Centre Ville Ecole Nationale nan tiyo n/a 19.638460 -72.060023 80 mai 2017/ Par OIM (Portes, fenetres, Parquet) Renforcement de la toiture 5 Artibonite Gonaives Centre Ville Eglise et Ecole Catherine Flon n/a 19.47354 -72.66978 254 Besoin en eau et assainissement mai 2017/ Par OIM 6 Artibonite Gonaives Centre Ville Lycée Bicentenaire n/a 19.46324 -72.67587 1024 Besoin en eau et assainissement mai 2017/ Par OIM 7 Artibonite Gonaives Morne Blanc Abri de Morne Blanc n/a 19.51262 -72.66917 259 Besoin en eau et assainissement mai 2017/ Par OIM 8 Artibonite Gonaives Praville Eglise APostolique n/a n/a n/a 90 Besoin en eau et assainissement n/a Comité Thématique Evacuation et Gestion Abri Provisoire (CTGAP) -

Earthquake-Affected Areas and Population Movement in Haiti

USG HUMANITARIAN ASSISTANCE TO HAITI FOR THE EARTHQUAKE CUBA KEY 73° W 72° W NORTHWEST Palmiste N N 20°USAID/OFDA USAID/FFP USAID/OTI 20° Port-de-Paix USAID/DR USAID/HAITI DoD Saint Louis Du Nord ECONOMIC RECOVERY AND Anse-a-foleur C MARKET SYSTEMS Jean Rabel Le Borgne Monte Cristi K EMERGENCY RESPONSE ACTIVITIES NORTHWEST Port-margot Cap-Haitien HEALTH Bassin-bleu ç Quartier Limbe HUMANITARIAN AIR SERVICE Marin Caracol b Baie-de-Henne Pilate Acul HUMANITARIAN COORDINATION Gros Morne Plaine Phaeton Anse Rouge Du Nord Du Nord Limonade Fort-Liberte B AND INFORMATION MANAGEMENT Plaisance Trou-du-nord NORNORTHTH Milot Ferrier INFRASTRUCTURE REHABILITATION Terre-neuve Sainte Suzanne o Dondon Grande Riviera Quanaminthe Dajabon LOGISTICS AND RELIEF COMMODITIES Du Nord Perches a Marmelade Gonaives Bahon NUTRITION Ennery Saint-raphael NORTHEAST F Vallieres G PROTECTION Ranguitte Affected Areas Saint Michel Mont Organise I SHELTER AND SETTLEMENTS ARARTIBONITETIBONITE De L'attalaye Pignon DoD USAID/DR La Victoire TITLE II EMERGENCY FOOD a a FH I ç USAR ; J Ga Dessalines Cerca ∑ TRANSITION INITIATIVE F HHS WFP ro Grande-Saline Carvajal ç b a m Maissade Cerca-la-source ; URBAN SEARCH AND RESCUE M Implementing Partners K WHO ia Petite-riviere- Hinche ç m de-l'artibonite WATER, SANITATION, AND HYGIENE i, Saint-Marc J F 02. .10 InterAction B WFP and NGOs L 10 to IOM Chemonics Thomassique REPUBLIC DOMINICAN a Po Verrettes ∑ r N t- CENTER N 19° OCHA B DAI au 19° ∑ -P r Peace Corps Internews in B ∑ ce BaptisteEliasWEST Pina RI Jç USAID/DR ç Belladere Mirebalais -

Cholera Treatment Facility Distribution for Haiti

municipalities listed above. listed municipalities H C A D / / O D F I **Box excludes facilities in the in facilities excludes **Box D A du Sud du A S Ile a Vache a Ile Ile a Vache a Ile Anse a pitres a Anse Saint Jean Saint U DOMINICAN REPUBLIC municipalities. Port-au-Prince Port-Salut Operational CTFs : 11 : CTFs Operational Delmas, Gressier, Gressier, Delmas, Pétion- Ville, and and Ville, G Operational CTFs : 13 : CTFs Operational E T I O *Box includes facilities in Carrefour, in facilities includes *Box N G SOUTHEAST U R SOUTH Arniquet A N P Torbeck O H I I T C A I Cote de Fer de Cote N M Bainet R F O Banane Roche A Bateau A Roche Grand Gosier Grand Les Cayes Les Coteaux l *# ! Jacmel *# Chantal T S A E H T U O SOUTHEAST S SOUTHEAST l Port à Piment à Port ! # Sud du Louis Saint Marigot * Jacmel *# Bodarie Belle Anse Belle Fond des Blancs des Fond # Chardonnières # * Aquin H T U O S SOUTH * SOUTH *# Cayes *# *# Anglais Les *# Jacmel de Vallée La Perrin *# Cahouane La Cavaillon Mapou *# Tiburon Marbial Camp Vieux Bourg D'Aquin Bourg Vieux Seguin *# Fond des Negres des Fond du Sud du Maniche Saint Michel Saint Trouin L’Asile Les Irois Les Vialet NIPPES S E P P I NIPPES N Fond Verrettes Fond WEST T S E WEST W St Barthélemy St *# *#*# Kenscoff # *##**# l Grand Goave #Grand #* * *#* ! Petit Goave Petit Beaumont # Miragoane * Baradères Sources Chaudes Sources Malpasse d'Hainault GRAND-ANSE E S N A - D N A R GRAND-ANSE G Petite Riviere de Nippes de Riviere Petite Ile Picoulet Ile Petion-Ville Ile Corny Ile Anse Ganthier Anse-a-Veau Pestel -

Community Radios April17

Haiti: Communication with communities - Mapping of community radio stations (Avr. 2017) La Tortue Bwa Kayiman 95.9 Port De Paix Zèb Tènite Saint Louis Kòn Lanbi 95.5 du Nord Anse A Foleur Jean Rabel Chamsolme Vwa kominotè Janrabèl Borgne Quartier Morin Bas Limbe Cap Haitien Vwa Liberasyon Mole Saint Nicolas Nord Ouest Bassin Bleu Pèp la 99.9 Port Margot Gros Morne Fransik 97.9 Pilate Plaine Baie de Henne Vwa Gwo Mòn 95.5 Eko 94.1 du Nord Caracol Bombardopolis Limbe Vestar FM Anse Rouge Milot Limonade Acul du Nord Terrier Rouge Ferrier Solidarité Terre Neuve Plaisance Natif natal Nord Trou du Nord Fort Liberte Zèb Ginen 97.7 Radyo Kominotè Sainte Suzanne Nòdès 92.3 Marmelade Gonaives Ouanaminthe Trans Ennery Dondon Nord Est Massacre Unité Bahon Valliere Capotille St. Raphael Tropicale 89.9 Capotille FM Ranquitte L'Estere La Victoire Mont Organise Saint-Michel de l'Attal Mombin Legend Desdunes Inite Sen Michel Pignon Crochu Carice Artibonite Tèt Ansanm 99.1 Grande Saline Communes ayant au moins Cerca Carvajal Dessalines/Marchandes une radio communautaire Maissade Radyo kominotè Mayisad Cerca La Source Communes sans Hinche radio communautaire Saint-Marc Vwa Peyizan 93.9 Imperial Petite Riviere de l'Artibonite Thomassique Cosmos Centre Xplosion Verrettes Thomonde Chandèl FM 106.1 Makandal 101.5 Xaragua 89.5 Grand’Anse 95.9 Boucan Carre Power Mix 97.5 Pointe A Raquette La Chapelle Kalfou 96.5 Arcahaie Lascahobas Tropette Evangelique 94.3 Belladere Orbite 100.7 Saut d'Eau Tet Ansanm 105.9 Anse A Galet Mirebalais CND 103.5 Cabaret Tera 89.9 -

Comite Departemental Nord De Gestion Des Risques Et Des Desastres Plan

1 COMITE DEPARTEMENTAL NORD DE GESTION DES RISQUES ET DES DESASTRES PLAN DE CONTINGENCE DEPARTEMENTAL 2013 2 DRAFT DU PLAN DE CONTINGENCE 2013 Table des Matières 1. RESUME EXECUTIF 2. DESCRIPTION DU CONTEXTE 2.1. Contexte politique 2.2. Contexte physique et environnemental 2.3. Contexte économique et social 2.4. Contexte sanitaire 2.5. Energie et infrastructures 3. RISQUE RETENUS POUR LE PLA N DE CONTINGENCE 3.1 Risques identifies 3.2 Analyse du risque par commune 3.3 Capacité locale d’adaptation et de réponse 4. CADRE GENERALE DE LA REPONSE EN HAITI 4.1 Le Système National de Gestion des Risques et des Désastres 4.2Mission 4.3. Organisation 4.4 . Analyse de la capacité de réponse 4.4.1. Couverture actuelle 4.5. Les outils de référence 3 4.6 Partenariat avec la Communauté Internationale 5. PORTEE ET LIMITES DU PLAN DE CONTINGENCE 2013 6. DEFINITION DU SCENARIO RETENU DANS LE PLAN DE CONTINGENCE 6.1 Guide operationnel d’urgence 6.2 Evaluation Rapide des dégats 6.3 Operations 6.4. Analyse et risques retenus 6.5. Classification des zones a risques 6.6. Définition du scenario et hypothèses de planification 7. ACTIVATION DU PLAN DE CONTINGENCE 8. ENJEUX ACTUELS, OBJECTIFS ET CADRE DE COORDINATION 8.1Enjeux 8.2 Objectifs 8.3 Cadre de coordination structurelle et opérationnelle 8.4 Le système de commandement 8.5 La chaine de communication 8.6 Points focaux pour le plan de contingence 8.7 Suppositions critiques 9. CADRE OPERATIONNEL 9.1 Procédures de réaction immédiate – 12 premières heures 9.2 Matrice de réaction rapide 9.3 Evaluation rapide -

Haiti: Ouragan Matthew 3W - Santé (8 Nov 2016)

Haiti: Ouragan Matthew 3W - Santé (8 nov 2016) La Tortue Port De Paix Saint Louis du Nord Jean Rabel Chamsolme Anse A Foleur Borgne Mole Saint Nicolas Bassin Bleu Port Margot Bas Limbe Cap Haitien Gros Morne Pilate Bombardopolis Baie de Henne Plaine du Nord Limonade Caracol Anse Rouge Limbe Milot Terrier Rouge Ferrier Terre Neuve Acul du Nord Plaisance Quartier Morin Trou du Nord Fort Liberte Marmelade Sainte Suzanne Ennery Dondon Ouanaminthe Gonaives Perches Grande Riviere Du Nord Bahon Valliere Capotille Nombre d’organisations St. Raphael Ranquitte Mont Organise La Victoire Carice L'Estere Saint-Michel de l'Attal par commune Pignon Mombin Crochu Desdunes Grande Saline Cerca Carvajal 1 Dessalines/Marchandes Maissade Cerca La Source 2 Hinche Saint-Marc Petite Riviere de l'Art Thomassique Verrettes Thomonde Boucan Carre La Chapelle Arcahaie Pointe A Raquette Lascahobas Belladere Saut d'Eau Cabaret Mirebalais Anse A Galet Savanette Cornillon/Grd Bois Bonbon Thomazeau Abricots Cite Soleil Delmas Tabarre Dame-Marie Roseaux Grand Boucan Corail Port-au-Prince Croix-Des-Bouquets Chambellan Jeremie Gressier Petion-Ville Ganthier Moron Baraderes Anse A Veau Anse d'Hainault Pestel Petite Riviere de Nippes Carrefour Beaumont Petit Trou De Nippes Arnaud Leogane Les Irois Paillant Kenscoff Maniche L'Asile Petit Goave Les Anglais Miragoane Grand-Goave Tiburon Camp Perrin Cavaillon Fonds Des Negres Fonds Verrettes Chardonnieres Chantal Jacmel Port-a-Piment St. Louis du Sud Aquin La Vallee Marigot Belle Anse Torbeck Les Cayes Cayes-Jacmel Grand Gosier Coteaux Cotes de Fer Bainet Thiotte Roche-A-Bateau Arniquet Anse A Pitre Port-Salut Ile A Vache St. -

WATER RESOURCES ASSESSMENT of HAITI August 1999

WATER RESOURCES ASSESSMENT OF HAITI August 1999 Haiti Dominican Republic US Army Corps of Engineers Mobile District and Topographic Engineering Center Water Resources Assessment of Haiti Executive Summary Haiti is one of the most densely populated countries in the world and one of the poorest in the Western Hemisphere. The population has already outstripped domestic food production, and it is estimated that the population will be 8 million by the year 2000. One-third of the population lives in the Département de l’Ouest where Port-au-Prince is located. Heavy migration from rural areas to towns and cities occurring over the past decade has adversely affected the distribution of the water supply. Access to water and sanitation facilities is inadequate, contributing to poor living conditions, disease, and a high mortality rate. In 1990 only 39 percent of the 5.9 million residents had adequate access to water and only 24 percent to sanitation. The lack of potable water for basic human needs is one of the most critical problems in the country. Given the rainfall and abundant water resources, there is adequate water to meet the water demands, but proper management to develop and maintain the water supply requirements is lacking. However, the water supply sector is undergoing complete transformation. Although currently there is no comprehensive water policy, progress is being made towards establishing a national water resources management policy. Numerous agencies and non-government organizations (NGO’s) are working to provide water, many of which conduct their missions with little or no coordination with other agencies, which creates duplication of work and inefficient use of resources.