THE ANCIENTS and the POSTMODERNS on the Historicity of Forms

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Istitutiones Iuris” of Albanian Consuetudinary Law

E-ISSN 2281-4612 Academic Journal of Interdisciplinary Studies Vol 4 No 2 ISSN 2281-3993 MCSER Publishing, Rome-Italy July 2015 “Istitutiones Iuris” of Albanian Consuetudinary Law Dr. Eugen Pepa Head of Departement of Justice, Faculty of Political Juridical Sciences, University “AleksanderMoisiu”, Durrës, Albania Email: [email protected] Doi:10.5901/ajis.2015.v4n2p337 Abstract The custom is among the sources of law, definitely, the most distant in time. Our legal tradition has been transmitted orally from generation to generation through the centuries and it bares these language elements that are considered fundamental for our people’s identity. Our society was shaped over the centuries under secular foreign occupation, and in full lack of a state authority to be represented with. Despite this, the juridical oral tradition and this kind of peculiar language managed to cross the millennia through its customs, creating and cultivating social and juridical institutions which have served to shape a collective conscience that made it possible for the modern state to be founded. Our analysis will concentrate principally in the representative values of the social belongings, creating the legal basis of the Albanian ethos and ethnos, which are always served as an autochthonous legal source. This might dispatch social justice values and human dignity. This analysis deepens its focus mainly in the strongholds of the common law; highlighting those social and legal institutions, that on our point of view have had the greatest influence in the creation of our national consciousness. Keywords: common law, legal tradition, society, institution etc. Il diritto consuetudinario è fonte giuridica universalmente presente fin dai primordi della storia umana. -

103 the Music Library of the Warsaw Theatre in The

A. ŻÓRAWSKA-WITKOWSKA, MUSIC LIBRARY OF THE WARSAW..., ARMUD6 47/1-2 (2016) 103-116 103 THE MUSIC LIBRARY OF THE WARSAW THEATRE IN THE YEARS 1788 AND 1797: AN EXPRESSION OF THE MIGRATION OF EUROPEAN REPERTOIRE ALINA ŻÓRAWSKA-WITKOWSKA UDK / UDC: 78.089.62”17”WARSAW University of Warsaw, Institute of Musicology, Izvorni znanstveni rad / Research Paper ul. Krakowskie Przedmieście 32, Primljeno / Received: 31. 8. 2016. 00-325 WARSAW, Poland Prihvaćeno / Accepted: 29. 9. 2016. Abstract In the Polish–Lithuanian Common- number of works is impressive: it included 245 wealth’s fi rst public theatre, operating in War- staged Italian, French, German, and Polish saw during the reign of Stanislaus Augustus operas and a further 61 operas listed in the cata- Poniatowski, numerous stage works were logues, as well as 106 documented ballets and perform ed in the years 1765-1767 and 1774-1794: another 47 catalogued ones. Amongst operas, Italian, French, German, and Polish operas as Italian ones were most popular with 102 docu- well ballets, while public concerts, organised at mented and 20 archived titles (totalling 122 the Warsaw theatre from the mid-1770s, featured works), followed by Polish (including transla- dozens of instrumental works including sym- tions of foreign works) with 58 and 1 titles phonies, overtures, concertos, variations as well respectively; French with 44 and 34 (totalling 78 as vocal-instrumental works - oratorios, opera compositions), and German operas with 41 and arias and ensembles, cantatas, and so forth. The 6 works, respectively. author analyses the manuscript catalogues of those scores (sheet music did not survive) held Keywords: music library, Warsaw, 18th at the Archiwum Główne Akt Dawnych in War- century, Stanislaus Augustus Poniatowski, saw (Pl-Wagad), in the Archive of Prince Joseph musical repertoire, musical theatre, music mi- Poniatowski and Maria Teresa Tyszkiewicz- gration Poniatowska. -

A Guide to Post-Classical Works of Art, Literature, and Music Based on Myths of the Greeks and Romans

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 112 438 CS 202 298 AUTHOR Smith, Ron TITLE A Guide to Post-Classical Works of Art, Literature, and Music Based on Myths of the Greeks and Romans. PUB DATE 75 NOTE 40p.; Prepared at Utah State University; Not available in hard copy due to marginal legibility of original document !DRS PRICE MF-$0.76 Plus Postage. HC Not Available from EDRS. DESCRIPTORS *Art; *Bibliographies; Greek Literature; Higher Education; Latin Literature; *Literature; Literature Guides; *Music; *Mythology ABSTRACT The approximately 650 works listed in this guide have as their focus the myths cf the Greeks and Romans. Titles were chosen as being (1)interesting treatments of the subject matter, (2) representative of a variety of types, styles, and time periods, and (3) available in some way. Entries are listed in one of four categories - -art, literature, music, and bibliography of secondary sources--and an introduction to the guide provides information on the use and organization of the guide.(JM) *********************************************************************** Documents acquired by ERIC include many informal unpublished * materials not available from other sources. ERIC makes every effort * * to obtain the best copy available. Nevertheless, items of marginal * * reproducibility are often encountered and this affects the quality * * of the microfiche and hardcopy reproductions ERIC makes available * * via the ERIC Document Reproduction Service (EDRS). EDRS is not * responsible for the quality of the original document. Reproductions * * supplied -

A Culture of Recording: Christopher Raeburn and the Decca Record Company

A Culture of Recording: Christopher Raeburn and the Decca Record Company Sally Elizabeth Drew A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Sheffield Faculty of Arts and Humanities Department of Music This work was supported by the Arts & Humanities Research Council September 2018 1 2 Abstract This thesis examines the working culture of the Decca Record Company, and how group interaction and individual agency have made an impact on the production of music recordings. Founded in London in 1929, Decca built a global reputation as a pioneer of sound recording with access to the world’s leading musicians. With its roots in manufacturing and experimental wartime engineering, the company developed a peerless classical music catalogue that showcased technological innovation alongside artistic accomplishment. This investigation focuses specifically on the contribution of the recording producer at Decca in creating this legacy, as can be illustrated by the career of Christopher Raeburn, the company’s most prolific producer and specialist in opera and vocal repertoire. It is the first study to examine Raeburn’s archive, and is supported with unpublished memoirs, private papers and recorded interviews with colleagues, collaborators and artists. Using these sources, the thesis considers the history and functions of the staff producer within Decca’s wider operational structure in parallel with the personal aspirations of the individual in exerting control, choice and authority on the process and product of recording. Having been recruited to Decca by John Culshaw in 1957, Raeburn’s fifty-year career spanned seminal moments of the company’s artistic and commercial lifecycle: from assisting in exploiting the dramatic potential of stereo technology in Culshaw’s Ring during the 1960s to his serving as audio producer for the 1990 The Three Tenors Concert international phenomenon. -

Who Was Protagoras? • Born in Abdêra, an Ionian Pólis in Thrace

Recovering the wisdom of Protagoras from a reinterpretation of the Prometheia trilogy Prometheus (c.1933) by Paul Manship (1885-1966) By: Marty Sulek, Ph.D. Indiana University Lilly Family School of Philanthropy For: Workshop In Multidisciplinary Philanthropic Studies February 10, 2015 Composed for inclusion in a Festschrift in honour of Dr. Laurence Lampert, a Canadian philosopher and leading scholar in the field of Nietzsche studies, and a professor emeritus of Philosophy at IUPUI. Adult Content Warning • Nudity • Sex • Violence • And other inappropriate Prometheus Chained by Vulcan (1623) themes… by Dirck van Baburen (1595-1624) Nietzsche on Protagoras & the Sophists “The Greek culture of the Sophists had developed out of all the Greek instincts; it belongs to the culture of the Periclean age as necessarily as Plato does not: it has its predecessors in Heraclitus, in Democritus, in the scientific types of the old philosophy; it finds expression in, e.g., the high culture of Thucydides. And – it has ultimately shown itself to be right: every advance in epistemological and moral knowledge has reinstated the Sophists – Our contemporary way of thinking is to a great extent Heraclitean, Democritean, and Protagorean: it suffices to say it is Protagorean, because Protagoras represented a synthesis of Heraclitus and Democritus.” Nietzsche, The Will to Power, 2.428 Reappraisals of the authorship & dating of the Prometheia trilogy • Traditionally thought to have been composed by Aeschylus (c.525-c.456 BCE). • More recent scholarship has demonstrated the play to have been written by a later, lesser author sometime in the 430s. • This new dating raises many questions as to what contemporary events the trilogy may be referring. -

Stanisław Moniuszko String Quartets 1 & 2 Juliusz Zarębski: Piano Quintet Op

Stanisław Moniuszko String Quartets 1 & 2 Juliusz Zarębski: Piano Quintet op. 34 Plawner Quintet Stanisław Moniuszko (1819–1872) String Quartet No. 1 in D minor 16'12 1 Allegro agitato 4'59 2 Andantino 3'57 3 Scherzo. Vivo 4'04 4 Finale. Un ballo campestre e sue consequenze. Allegro assai 3'12 String Quartet No. 2 in F major 15'12 5 Allegro moderato 5'50 6 Andante 4'43 7 Scherzo. Baccanale monacale. Allegretto – Trio 2'06 8 Finale. Allegro 2'33 Juliusz Zarębski (1854–1885) Piano Quintet op. 34 34'55 9 Allegro 9'46 10 Adagio 10'28 11 Scherzo. Presto 5'57 12 Finale. Presto 8'44 T.T.: 66'27 Plawner Quintet Piotr Plawner, violin Sibylla Leuenberger, violin Elżbieta Mrożek-Loska, viola Isabella Klim, violoncello Stanisław Moniuszko Piotr Sałajczyk, piano [9] All rights of the producer and of the owner of the work reserved. Unauthorized copying, hiring, renting, public performance and broadcasting of this record prohibited. cpo 555 124–2 Co-Production: cpo/Deutschlandfunk Kultur Recording: Andreaskirche Berlin/Wannsee, September 22–24, 2018 Recording Producer, Editing & Mastering: Michael Havenstein Executive Producers: Burkhard Schmilgun/Bettina C. Schmidt Cover Painting: Wladyslaw Podkowinski, »Un campo de Lupin«, 1891. Galería de Arte Polaco del siglo XIX (Lonja de los Paños, Sukiennice). Museo Nacional de Cracovia. Polonia. Ⓒ Photo: akg-images, 2019; Design: Lothar Bruweleit cpo, Lübecker Str. 9, D–49124 Georgsmarienhütte Juliusz Zarębski Ⓟ 2019 – Deutschlandradio – Made in Germany Anziehend in ihren Gegensätzen: sich der genius populi mitsamt seinem Temperament, jahrelang an der Schwindsucht dahin, Stanisław Moniu- Stanisław Moniuszko und Juliusz Zarębski seinem Melos und Rhythmus, seiner Geschichte und sei- szko wird ohne Vorwarnung aus seiner Tätigkeit heraus- nen Hoffnungen spontan wiedererkannte. -

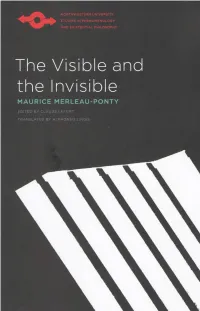

Maurice Merleau-Ponty,The Visible and the Invisible

Northwestern University s t u d i e s i n Phenomenology $ Existential Philosophy GENERAL EDITOR John Wild. ASSOCIATE EDITOR James M. Edie CONSULTING EDITORS Herbert Spiegelberg William Earle George A. Schrader Maurice Natanson Paul Ricoeur Aron Gurwitsch Calvin O. Schrag The Visible and the Invisible Maurice Merleau-Ponty Edited by Claude Lefort Translated by Alphonso Lingis The Visible and the Invisible FOLLOWED BY WORKING NOTES N orthwestern U n i v e r s i t y P r e s s 1968 EVANSTON Northwestern University Press www.nupress.northwestern.edu Originally published in French under the title Le Visible et l'invisible. Copyright © 1964 by Editions Gallimard, Paris. English translation copyright © 1968 by Northwestern University Press. First printing 1968. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America 15 14 13 12 11 ISBN-13: 978-0-8101-0457-0 isbn-io: 0-8101-0457-1 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication data are available from the Library of Congress Permission has been granted to quote from Jean-Paul Sartre, Being and Nothingness, trans. Hazel E. Barnes (New York: The Philosophical Library, 1956). @ The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences— Permanence o f Paper for Printed Library Materials, ansi Z39.48-1992. Contents Editor’s Foreword / xi Editorial Note / xxxiv T ranslatofs Preface / xl T h e Visib l e a n d t h e In v is ib l e : Philosophical Interrogation i Reflection and Interrogation / 3 a Interrogation and Dialectic / 50 3 Interrogation and Intuition / 105 4 The Intertwining—The Chiasm / 130 5 [a ppen d ix ] Preobjective Being: The Solipsist World / 156 W orking N otes / 165 Index / 377 Chronological Index to Working Notes / 279 Editor's Foreword How eve r e x p e c t e d it may sometimes be, the death of a relative or a friend opens an abyss before us. -

MODELING HEROINES from GIACAMO PUCCINI's OPERAS by Shinobu Yoshida a Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requ

MODELING HEROINES FROM GIACAMO PUCCINI’S OPERAS by Shinobu Yoshida A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Music: Musicology) in The University of Michigan 2011 Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Naomi A. André, Co-Chair Associate Professor Jason Duane Geary, Co-Chair Associate Professor Mark Allan Clague Assistant Professor Victor Román Mendoza © Shinobu Yoshida All rights reserved 2011 TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES ...........................................................................................................iii LIST OF APPENDECES................................................................................................... iv I. CHAPTER ONE........................................................................................................... 1 INTRODUCTION: PUCCINI, MUSICOLOGY, AND FEMINIST THEORY II. CHAPTER TWO....................................................................................................... 34 MIMÌ AS THE SENTIMENTAL HEROINE III. CHAPTER THREE ................................................................................................. 70 TURANDOT AS FEMME FATALE IV. CHAPTER FOUR ................................................................................................. 112 MINNIE AS NEW WOMAN V. CHAPTER FIVE..................................................................................................... 157 CONCLUSION APPENDICES………………………………………………………………………….162 BIBLIOGRAPHY.......................................................................................................... -

Cinema Ritrovato Di Gian Luca Farinelli, Vittorio Martinelli, Nicola Mazzanti, Mark-Paul Meyer, Ruud Visschedijk

Cinema Ritrovato di Gian Luca Farinelli, Vittorio Martinelli, Nicola Mazzanti, Mark-Paul Meyer, Ruud Visschedijk Iniziamo dalla foto che abbiamo scelto per il manifesto, perché è un’immagine rivelatrice dell’identità di questo festival. Ad un primo sguardo non suscita un interesse particolare. È la foto di scena di un film qualsiasi prodotto in un periodo in cui di cinema se ne faceva tanto, un’immagine come tante. Però se la guardiamo meglio vediamo che al centro della foto c’è uno dei grandi attori del cinema italiano, Aldo Fabrizi, il Don Pietro di Roma città aperta, alle prese con la giustizia. Ci accorgiamo anche che il set è il lato sud di Piazza Maggiore; si scorgono il Palazzo del Podestà, San Petronio, il Nettuno, Palazzo de’ Banchi. L’immagine inizia a intrigarci. Siccome il cinema italiano è da sempre fortemente romano, pochissimi sono stati i film girati a Bologna, almeno sino agli anni ’60. Ecco perché Hanno rubato un tram, il film da cui abbiamo sottratto quest’immagine, è una vera scoperta che ci giunge dal passato. Nonostante si tratti di una piccola produzione, di un film modesto, di cui all’epoca nessuno si accorse, poterlo vedere oggi è un’esperienza straordinaria perché ci porta nella Bologna di quarantasei anni fa e ci fa sentire tutta la distanza del tempo, le dimensioni della trasformazione, l’ampiezza dei cambiamenti, esperienza tanto più forte perché si tratta di immagini inaspettate di un film dimenticabile, che nessuno vedeva più da decenni. Il film è anche un curioso incontro tra generazioni diverse del cinema italiano. -

Katalogu FUND.Cdr

E U R O P E A N C H A M B E R C H O R A L F E S T I VA L O F A L B A N I A 2 0 1 0 4 rd EDITION, 17-19 OCTOBER 2010 In the occasion of 100th - Anniversary of “Mother Teresa''' Under the auspices of her Excellency Mrs. JOZEFINA TOPALLI Head of Albanian Parliament P R O G R A M 1 7 - 1 9 O C T O B E R 2 3 D E C E M B E R MTKRS EU COMMISSION SUPPORTED BY MINISTRY OF TOURISM, CULTURE, YOUTH & SPORTS DELEGATION OF THE EUROPEAN COMMISION IN ALBANIA 4 rd EDITION, 17-19 OCTOBER 2010 E U R O P E A N C H A M B E R C H O R A L F E S T I VA L O F A L B A N I A 2 0 1 0 MANAGING STAFF Suzana Turku Kashara President of Festival Besim Petrela Executive Director 069 20 59 466 Pjeter Guralumi Public Relations Coordinator 069 40 37 866 Milto Kutali Stage Director 068 40 18 191 Shaqir Rexhvelaj General Secretary of the Festival 067 20 75 960 Fatlinda Subashi International Relations 069 20 59 469 Admir Rexha Secretary 068 40 31 520 Fahri Karameti Assistant Besnik Shamku Transport 069 20 74 417 Suzana Turku Kashara artistic bodies about 14 choirs Zv/Ministre e Turizmit, participating in the fourth Kultures, Rinise dhe Sporteve edition of the European festival: Albania, Greece, Italy, The fourth edition of the Netherlands, Montenegro, Festival EUROPEAN Macedonia Bulgaria, France, Chamber Choirs 2010 Israel, Bosnia, Czech culminates with a very special Republic etc. -

Apocalypticism in Wagner's Ring by Woodrow Steinken BA, New York

Title Page Everything That Is, Ends: Apocalypticism in Wagner’s Ring by Woodrow Steinken BA, New York University, 2015 MA, University of Pittsburgh, 2018 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Dietrich School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2021 Committee Page UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH DIETRICH SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by Woodrow Steinken It was defended on March 23, 2021 and approved by James Cassaro, Professor, Music Adriana Helbig, Associate Professor, Music David Levin, Professor, Germanic Studies Dan Wang, Assistant Professor, Music Dissertation Director: Olivia Bloechl Professor, Music ii Copyright © by Woodrow Steinken 2021 iii Abstract Everything That Is, Ends: Apocalypticism in Wagner’s Ring Woodrow Steinken, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2021 This dissertation traces the history of apocalypticism, broadly conceived, and its realization on the operatic stage by Richard Wagner and those who have adapted his works since the late nineteenth century. I argue that Wagner’s cycle of four operas, Der Ring des Nibelungen (1876), presents colloquial conceptions of time, space, and nature via supernatural, divine characters who often frame the world in terms of non-rational metaphysics. Primary among these minor roles is Erda, the personification of the primordial earth. Erda’s character prophesies the end of the world in Das Rheingold, a prophecy undone later in Siegfried by Erda’s primary interlocutor and chief of the gods, Wotan. I argue that Erda’s role changes in various stage productions of the Ring, and these changes bespeak a shifting attachment between humanity, the earth, and its imagined apocalyptic demise. -

Maurice Merleau-Ponty: Phenomenology of Perception

Phenomenology of Perception ‘In this text, the body-organism is linked to the world through a network of primal significations, which arise from the perception of things.’ Michel Foucault ‘We live in an age of tele-presence and virtual reality. The sciences of the mind are finally paying heed to the centrality of body and world. Everything around us drives home the intimacy of perception, action and thought. In this emerging nexus, the work of Merleau- Ponty has never been more timely, or had more to teach us ... The Phenomenology of Perception covers all the bases, from simple perception-action routines to the full Monty of conciousness, reason and the elusive self. Essential reading for anyone who cares about the embodied mind.’ Andy Clark, Professor of Philosophy and Director of the Cognitive Science Program, Indiana University Maurice Merleau-Ponty Phenomenology of Perception Translated by Colin Smith London and New York Phénomènologie de la perception published 1945 by Gallimard, Paris English edition first published 1962 by Routledge & Kegan Paul First published in Routledge Classics 2002 by Routledge 11 New Fetter Lane, London EC4P 4EE 29 West 35th Street, New York, NY 10001 Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group This edition published in the Taylor and Francis e-Library, 2005. “To purchase your own copy of this or any of Taylor & Francis or Routledge’s collection of thousands of eBooks please go to www.eBookstore.tandf.co.uk.” © 1945 Editions Gallimard Translation © 1958 Routledge & Kegan Paul All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.