Alignment and Axiality in Anglo-Saxon Architecture: 6Th-11Th Centuries

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

First Evidence of Farming Appears; Stone Axes, Antler Combs, Pottery in Common Use

BC c.5000 - Neolithic (new stone age) Period begins; first evidence of farming appears; stone axes, antler combs, pottery in common use. c.4000 - Construction of the "Sweet Track" (named for its discoverer, Ray Sweet) begun; many similar raised, wooden walkways were constructed at this time providing a way to traverse the low, boggy, swampy areas in the Somerset Levels, near Glastonbury; earliest-known camps or communities appear (ie. Hembury, Devon). c.3500-3000 - First appearance of long barrows and chambered tombs; at Hambledon Hill (Dorset), the primitive burial rite known as "corpse exposure" was practiced, wherein bodies were left in the open air to decompose or be consumed by animals and birds. c.3000-2500 - Castlerigg Stone Circle (Cumbria), one of Britain's earliest and most beautiful, begun; Pentre Ifan (Dyfed), a classic example of a chambered tomb, constructed; Bryn Celli Ddu (Anglesey), known as the "mound in the dark grove," begun, one of the finest examples of a "passage grave." c.2500 - Bronze Age begins; multi-chambered tombs in use (ie. West Kennet Long Barrow) first appearance of henge "monuments;" construction begun on Silbury Hill, Europe's largest prehistoric, man-made hill (132 ft); "Beaker Folk," identified by the pottery beakers (along with other objects) found in their single burial sites. c.2500-1500 - Most stone circles in British Isles erected during this period; pupose of the circles is uncertain, although most experts speculate that they had either astronomical or ritual uses. c.2300 - Construction begun on Britain's largest stone circle at Avebury. c.2000 - Metal objects are widely manufactured in England about this time, first from copper, then with arsenic and tin added; woven cloth appears in Britain, evidenced by findings of pins and cloth fasteners in graves; construction begun on Stonehenge's inner ring of bluestones. -

The Frome 8, Piddle Catchmentmanagement Plan 88 Consultation Report

N 6 L A “ S o u t h THE FROME 8, PIDDLE CATCHMENTMANAGEMENT PLAN 88 CONSULTATION REPORT rsfe ENVIRONMENT AGENCY NATIONAL LIBRARY & INFORMATION SERVICE ANGLIAN REGION Kingfisher House. Goldhay Way. Orton Goldhay, Peterborough PE2 5ZR NRA National Rivers Authority South Western Region M arch 1995 NRA Copyright Waiver This report is intended to be used widely and may be quoted, copied or reproduced in any way, provided that the extracts are not quoted out of context and that due acknowledgement is given to the National Rivers Authority. Published March 1995 ENVIRONMENT AGENCY Hill IIII llll 038007 FROME & PIDDLE CATCHMENT MANAGEMENT PLAN CONSULTATION REPORT YOUR VIEWS The Frome & Piddle is the second Catchment Management Plan (CMP) produced by the South Wessex Area of the National Rivers Authority (NRA). CMPs will be produced for all catchments in England and Wales by 1998. Public consultation is an important part of preparing the CMP, and allows people who live in or use the catchment to have a say in the development of NRA plans and work programmes. This Consultation Report is our initial view of the issues facing the catchment. We would welcome your ideas on the future management of this catchment: • Hdve we identified all the issues ? • Have we identified all the options for solutions ? • Have you any comments on the issues and options listed ? • Do you have any other information or ideas which you would like to bring to our attention? This document includes relevant information about the catchment and lists the issues we have identified and which need to be addressed. -

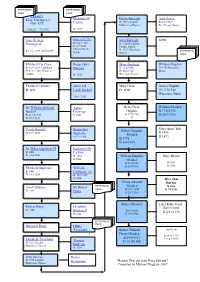

Meaden Descent from King Edward I Compiled by Michael Dugdale

EXTENDED EXTENDED TREE TREE Edward I Eleanore Of Henry Burleigh Amy Sexey King Plantagenet B: 1619 Langton B: 26/8/1627 1216 - 1272 Castile Maltravers, Dorset Bere Regis, Dorset. 17/6/1239 – 7/7/1307 D: 1290 Joan Of Acre Gilbert (Sir) The John Burleigh JANE Red De Clare Plantagenet B: 3/1654 Turners B: 2/9/1243. Puddle, Dorset Christ Church, B:1272. Acre ‘Holy Land’ D: 1727, Wareham Hants EXTENDED Dorset TREE Elizabeth De Clare Roger (Sir) Mary Burleigh William Dugdale B: 16/9/1295 Tewksbury Damory B: 11/4/1690 D: 1756 Wareham, D: 4?11/1360. Minories, D: 24/8/1766 Dorset Aldgate D: 1322 Wareham, Dorset Elizabeth Damory John (3rd Mary Dean Daniel Dugdale B: 1318 Lord) Bardolf D: 1800 D:17/3/1782 Wareham, Baker 1350 - 1363 Sir William 4th Lord Agnes Betty Dean William Meaden Bardolf Poynings Dugdale B 17/8/1756 B: 21/10/1349 D:1403 B 11/3/1766 D 30/9/1796 D: 29/1/1385 D Cecily Bardolf Brian (Sir) Mary Ann Clark Robert Dugdale D: 29/9/1432 B 1805 Stapleton Meaden 1377 - 1438 D 1892 B 1795 D 6/4/1845 Sir Miles Stapleton VI Katherine De B: 1408 La Pole D: 1/10/1466 B: 1416 William Dugdale Mary Brown D:1488 Meaden B 2/12/1828 B 1831 D 26/9/1903 D 1906 Elizabeth Stapleton William B: 1441 Calthorpe VII D: 18/2/1504 B: 30/1/1409 D:1494 Alice Jane Henry Edward Burton Ann Calthorpe Sir Robert EXTENDED Meaden B 1854 TREE B 22/1/ 1854 D 7/8/1923 D: 1494 Drury D 23/3/1918 Robert Meaden Ethel Ruby Good Robert Drury Elizabeth 2 B29/9/1890 D: 1589 Brudenell B 8/3/1884 D 8/11/1948 D:1542 D 29/9/1945 E XTENDED TREE Margaret Drury Henry Trenchard Robert William Ivy Wells Henry Meaden B 24/11/1913 Elizabeth Trenchard B 24/4/1912 D 14/3/1995 Thomas D 13 /4/1988 D: 1627 Lytchett Burleigh Maltravers, Dorset B: 1558 Henry Burleigh Hester B: 1590 Langton Heybourne Meaden Descent from King Edward I Maltravers, Dorset Compiled by Michael Dugdale. -

A303 Stonehenge E

1 A303 Stonehenge e m Amesbury to Berwick Down u l o V Report on Public Consultation September 2017 A303 Stonehenge, Amesbury to Berwick Down | HE551506 Table of contents Chapter Pages Executive summary 2 Background context 2 Scheme proposals presented for consultation 2 Consultation arrangements 3 Consultation response 3 Key considerations 5 Effectiveness and benefits of consultation 6 1 Introduction 7 2 A303 Stonehenge: Amesbury to Berwick Down Scheme proposals 9 2.1 Scheme proposals 9 3 How we undertook consultation 11 3.1 When we consulted 11 3.2 Who we consulted 11 3.3 How consultation was carried out 15 4 Overview of consultation feedback 20 4.1 General 20 4.2 Breakdown of total responses 20 4.3 Questionnaire responses: Questions 1-4 21 4.4 Themes arising from comments made against Questions 1-7 23 4.5 Feedback data from Questions 8-10 24 5 Matters raised and Highways England response 27 5.1 General 27 5.2 Matters raised by the public with Highways England’s response 27 5.3 Responses by statutory bodies 107 5.4 Responses by non-statutory organisations and other groups 115 5.5 Matters raised by statutory bodies and non-statutory organisations and groups with Highways England’s response 153 5.6 Matters raised by landholders with Highways England’s response 170 6 Summary of Feedback and Key Considerations 190 6.1 Summary of consultation feedback 190 6.2 Key considerations 197 7 Conclusions 199 7.1 Purpose of the consultation 199 7.2 Summary of what was done 199 7.3 Did the consultation achieve its purpose? 201 Abbreviations List 203 Glossary 204 Appendices 207 Page 1 of 207 A303 Stonehenge, Amesbury to Berwick Down | HE551506 Executive summary Background context The A303 Stonehenge scheme is part of a programme of improvements along the A303 route aimed at improving connectivity between London and the South East and the South West. -

Federation to Hold Super Sunday on August 29 by Reporter Staff Contact the Federation Campaign

August 13-26, 2021 Published by the Jewish Federation of Greater Binghamton Volume L, Number 17 BINGHAMTON, NEW YORK Federation to hold Super Sunday on August 29 By Reporter staff contact the Federation Campaign. When the The Jewish Federation of Greater Bing- at [email protected] community pledges hamton will hold Super Sunday on Sunday, or 724-2332. Marilyn early, the allocation August 29, at 10 am, at the Jewish Commu- Bell is the chairwom- process is much eas- nity Center, 500 Clubhouse Rd., Vestal. It an of Campaign 2022. ier. We also want the will feature a brunch, comedy by comedian “We are hoping snow birds to have Josh Wallenstein and a showing of the film to get community an opportunity to “Fiddler: A Miracle of Miracles” about the members to pledge gather before they Broadway musical “Fiddler on the Roof.” early again this year,” leave for sunnier Larry Kassan, who has directed productions said Shelley Hubal, climates this fall.” of the musical, will facilitate the film discus- executive director of Bell noted how im- sion. The cost of the brunch and film is $15 the Federation. “We started the 2021 Cam- portant the Campaign is to the community. and reservations are requested by Sunday, paign with almost 25 percent of the pledges “As I begin my fourth year as Campaign August 22. To make reservations, visit already made. That helped to cut back on chair, I know – and I know that you know the Federation website, www.jfgb.org/, or the manpower we needed to get through the – how essential our local organizations are to the Jewish community,” she said. -

Hinkley Point C: Building a Somerset Legacy 18 | FEATURE

The Official Magazine of Somerset Chamber of Commerce August / September 2017 Hinkley Point C: Building a Somerset Legacy 18 | FEATURE 6 | CHAMBER NEWS New manager appointed for Hinkley Supply Chain Team 10 | FOCUS ON: MARKETING & PR Chamber Members discuss elements of their sector 32 | BUSINESS NEWS Citizens rights following Brexit Creating opportunities Get in touch to to connect – stimulating find out how we business growth for Somerset can help your business grow Become a member today - membership packages starting from as little as £150 per year somerset-chamber.co.uk T: 01823 444924 E: [email protected] 3 CONTENTS First Word 4 Patron News 5 Chamber News 6-9 Focus On 10-11 Members Area 12-17 Feature 18-21 #WellConnected 22-23 The Big Interview 24-25 18 | FEATURE Members News 26-31 HINKLEY - A SOMERSET LEGACY Business News 32-33 Town Chamber News 34 5 | PATRON NEWS 10 | FOCUS ON Disclaimer The views expressed in this magazine are 34 | TOWN not necessarily those of the Chamber. This CHAMBER publication (or any part thereof) may not be NEWS reproduced, transmitted or stored in print or electronic format (including, but not limited to, any online service, any database or any part of the internet), or in any other format in any media whatsoever, without the 12 | MEMBERS AREA prior written permission of the publisher. Although every effort is made to ensure the accuracy of information contained in the magazine, Somerset Chamber do not accept any responsibility for any omissions or inaccuracies it contains. Somerset Chamber of Commerce We are social Equity House Blackbrook Park Avenue Blackbrook Business Park @chambersomerset Taunton, Somerset TA1 2PX Editorial and advertising: Watch us on YouTube E: [email protected] T: 01823 444924 Printers: Print Guy, Somerset Find us on LinkedIn Design by: Thoroughbred Design & Print, Somerset 4 Get in touch FIRST WORD Marketing Scarlett Scott-Collins Marketing Supervisor We all live in what appears to be an ever-increasing paced life, with technology at the heart of change. -

SGP Final Report V5 5 January 2014

Somerset Growth Plan 2014-2020 Operational Document January 2014 Contents Strategic Framework ............................................................................................................................... i 1. Introduction ................................................................................................................................... 7 2. Opportunities and Barriers to Growth ......................................................................................... 11 3. The Geography of Growth in Somerset ........................................................................................ 16 4. Our Approach to Growth in Somerset ......................................................................................... 20 5. Investment Packages and Projects ............................................................................................... 23 6. Governance and Next Steps ......................................................................................................... 32 Appendices A Principles of Growth B SWOT, Barriers and Economic Data C Methodology for Target Setting D Funders of Growth E Projects and Prioritisation F Project Details Version Number: 5.5 Date: January 2014 Somerset Growth Plan 2014 – 2020 January 2014 Strategic Framework This document sets out Somerset’s plans to promote growth. Between now and 2020 we will enable the delivery of growth, and also lay the foundations for long-term sustainable economic growth in the years after this. Purpose of the Growth Plan The -

W:N .~ I) LQ11 Ref: ENF- L

UNITED STATES ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION AGENCY REGION 8 1595 Wynkoop Street DENVER, CO 80202-1129 Phone 800-227-8917 http://.Nww.epa.gov/regioo08 W:N .~ I) LQ11 Ref: ENF- L L RGENT LEGAl. MAlTER PROMPT REPLY NECESSAR Y CERTIFIED MAIL! RETURN RECEIPT REQUEST ED UNSF Railway Company Attn: David M. Smith Manager. Environmental Remediation 825 Great Northern l3lvd .. Suitt.': J 05 I Idena., Montana 59601 John P. Ashworth Rnhl:rt B. l.owry K.. :II. :\IIC'flllan & Rllllstcin. L.L.P. _,,~O S. W. Yamhill. Suite 600 Ponland. OR 97204-1329 Rc: RiffS Special Notice Response: Settlement Proposal and Demand Letter for the ACM Smelter and Rcfin~ry Site. Cascade County. MT (SSID #08-19) Ikar M!.":ssrs. Smith. Ashworth and Lowry: I hi s Icuef address!"!:.; thc response ofI3NSF Railway Company (BNSF), formerly (3urlington Northern and 'laJlt:1 h ..' Company. to the General and Special Notice and Demand leuer issued by the United States I'm irunrl1l:nta[ Protection Agency (EPA) on May 19,20 11 (Special Notice). for certain areas within Operable Un it I (OU I) at Ihe ACM Smelter and Refinery Site, near Great Falls. Montana (Sile). Actions ilt the Site are bc:ing taken pursuant to the Comprchc:nsive Environmental Response. Compensation. and I.iability Act of 1980 (CERCLA). 42 U.S.C. § 9601. el .l'c'I. The Special Notice informed BNSF of the Rt:mediallnvcstigation and Feasibility Study (RUFS) work determined by the EPA to be necessary at au I at the Site. notified BNSF of its potential liability at the Site under Section 107(a) ofeCRCLA 42 U.S.C. -

Somerset Growth Plan

Somerset Growth Plan 2017 - 2030 Technical Document Contents Executive Summary .................................................................................................................................. i 1 Introduction .................................................................................................................................... 1 2 Somerset’s Economy and Context .................................................................................................. 5 3 Vision and Objectives .................................................................................................................... 14 4 Frameworks for Growth ................................................................................................................ 16 5 Governance ................................................................................................................................... 35 Version Number: FINAL 1.6 Date: June 2017 Executive Summary Background and context The Growth Plan for Somerset aims to: Create a shared ambition and vision for sustainable and productive growth Support the delivery of infrastructure and housing to enable growth to take place Increase the scale, quality and sustainability of economic opportunity in Somerset Ensure participation and access to these opportunities for local residents Growth is important to Somerset because: It will enable us to improve the quality of life for residents and their economic wellbeing It will enable us to increase our economically active workforce -

Preliminary Outline Assessment of the Impact of A303 Improvements On

Preliminary Outline Assessment of the impact of A303 improvements on the Outstanding Universal Value of the Stonehenge Avebury and Associated Sites World Heritage property Nicola Snashall BA MA PhD MIfA National Trust Christopher Young BA MA DPhil FSA Christopher Young Heritage Consultancy August 2014 ©English Heritage and The National Trust Preliminary Outline Impact Assessment of A303 improvements on the Outstanding Universal Value of the Stonehenge and Avebury World Heritage property August 2014 Executive Summary The Government have asked the Highways Agency to prepare feasibility studies for the improvement of six strategic highways in the UK. One of these is the A303 including the single carriageway passing Stonehenge. This study has been commissioned by English Heritage and the National Trust to make an outline preliminary assessment of the potential impact of such road improvements on the Outstanding Universal Value of the World Heritage property. A full impact assessment, compliant with the ICOMOS guidance and with EU and UK regulations for Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) would be a much larger task than this preliminary assessment. It would be prepared by the promoter of a road scheme and would require more supporting material and more detailed analysis of impacts. The present study is an outline preliminary assessment intended to inform the advice provided by the National Trust and English Heritage to the Highways Agency and the Department for Transport. It deals only with impact on Outstanding Universal Value and does not examine impacts on nationally or locally significant heritage. The objectives of the study can be summarised as: 1. Review changes in international and national policy and in our understanding of the Outstanding Universal Value of the World Heritage property to set the context for the assessment of impact of potential options for improvement of the A303; 2. -

7Th Sunday After Pentecost Commemoration of the Fathers Of

7th Sunday After Pentecost Heiromartyr Hermolaus and those with him 26 July / 8 August Resurrection Tropar, Tone 6: The angelic powers were at Thy tomb; / the guards became as dead men. / Mary stood by Thy grave, / seeking Thy most pure Body. / Thou didst capture hell, not being tempted by it. / Thou didst come to the Virgin, granting life. / O Lord who didst rise from the Dead, / Glory to Thee! Troparion of the Hierornartyrs tone 3: You faithfully served the Lord as true priests, O Saints,/ and joyfully followed the path of martyrdom./ O Hermolaus, Hermippus and Hermocrates,/ three-pillared foundation of the Church,/ pray unceasingly that we may be preserved from harm. Resurrection Kondak, Tone 6: When Christ God the Giver of Life, / raised all of the dead from the valleys of misery with His Mighty Hand, / He bestowed resurrection on the human race. / He is the Saviour of all, the Resurrection, the Life, and the God of All. Kontakion of St Hermolaus tone 4: As a godly priest thou didst receive the crown of martyrdom:/ for as a good shepherd of Christ's flock thou didst prevent the sacrifice of idols./ Thou wast a wise teacher of Panteleimon/ and we praise and venerate thee, crying:/ Deliver us from harm by thy prayers, O Father Hermolaus. Matins Gospel VII EPISTLE: ST. PAUL’S LETTER TO THE ROMANS 15: 1-7 We then who are strong ought to bear with the scruples of the weak, and not to please ourselves. Let each of us please his neighbour for his good, leading to edification. -

Stonehenge A303 Improvement: Outline Assessment of the Impacts

Stonehenge A303 improvement: outline assessment of the impacts on the Outstanding Universal Value of the World Heritage property of potential route options presented by Highways England for January 2017 Nicola Snashall BA MA PhD MCIfA National Trust Christopher Young BA MA DPhil FSA Christopher Young Heritage Consultancy January 2017 ©Historic England and the National Trust Stonehenge A303 improvements: outline assessment of the impacts on the Outstanding Universal Value of the World Heritage property of potential route options presented by Highways England for January 2017 Executive Summary Introduction In 2014, English Heritage (now Historic England) and the National Trust commissioned an assessment (Snashall, Young 2014) on the potential impact of new road options, including a tunnel, for the A303 within the Stonehenge component of the Stonehenge, Avebury and Associated Sites World Heritage property. Since at that time, there were no detailed proposals, that report considered four possible alternatives and concluded that, of these, an off-line route with a tunnel of 2.9kms length would be the most deliverable solution. The government remains committed to improving the A303 and to funding sufficient for a tunnel of at least 2.9kms length within the World Heritage property. Highways England are consulting in early 2017 on route options developed since 2014 for this road scheme through the World Heritage property and bypassing Winterbourne Stoke village to the west. This report is an outline assessment of these initial options on the Outstanding Universal Value (OUV) of the World Heritage property. It has been commissioned to assess the impact of the latest road options in the light of updated archaeological information.