Characterization of a Microsomal Retinol Dehydrogenase Gene from Amphioxus: Retinoid Metabolism Before Vertebrates

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Methionine Sulfoxide Reductase a Is a Stereospecific Methionine Oxidase

Methionine sulfoxide reductase A is a stereospecific methionine oxidase Jung Chae Lim, Zheng You, Geumsoo Kim, and Rodney L. Levine1 Laboratory of Biochemistry, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, Bethesda, MD 20892-8012 Edited by Irwin Fridovich, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, NC, and approved May 10, 2011 (received for review February 10, 2011) Methionine sulfoxide reductase A (MsrA) catalyzes the reduction Results of methionine sulfoxide to methionine and is specific for the S epi- Stoichiometry. Branlant and coworkers have studied in careful mer of methionine sulfoxide. The enzyme participates in defense detail the mechanism of the MsrA reaction in bacteria (17, 18). against oxidative stresses by reducing methionine sulfoxide resi- In the absence of reducing agents, each molecule of MsrA dues in proteins back to methionine. Because oxidation of methio- reduces two molecules of MetO. Reduction of the first MetO nine residues is reversible, this covalent modification could also generates a sulfenic acid at the active site cysteine, and it is function as a mechanism for cellular regulation, provided there reduced back to the thiol by a fast reaction, which generates a exists a stereospecific methionine oxidase. We show that MsrA disulfide bond in the resolving domain of the protein. The second itself is a stereospecific methionine oxidase, producing S-methio- MetO is then reduced and again generates a sulfenic acid at the nine sulfoxide as its product. MsrA catalyzes its own autooxidation active site. Because the resolving domain cysteines have already as well as oxidation of free methionine and methionine residues formed a disulfide, no further reaction forms. -

Enzyme DHRS7

Toward the identification of a function of the “orphan” enzyme DHRS7 Inauguraldissertation zur Erlangung der Würde eines Doktors der Philosophie vorgelegt der Philosophisch-Naturwissenschaftlichen Fakultät der Universität Basel von Selene Araya, aus Lugano, Tessin Basel, 2018 Originaldokument gespeichert auf dem Dokumentenserver der Universität Basel edoc.unibas.ch Genehmigt von der Philosophisch-Naturwissenschaftlichen Fakultät auf Antrag von Prof. Dr. Alex Odermatt (Fakultätsverantwortlicher) und Prof. Dr. Michael Arand (Korreferent) Basel, den 26.6.2018 ________________________ Dekan Prof. Dr. Martin Spiess I. List of Abbreviations 3α/βAdiol 3α/β-Androstanediol (5α-Androstane-3α/β,17β-diol) 3α/βHSD 3α/β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase 17β-HSD 17β-Hydroxysteroid Dehydrogenase 17αOHProg 17α-Hydroxyprogesterone 20α/βOHProg 20α/β-Hydroxyprogesterone 17α,20α/βdiOHProg 20α/βdihydroxyprogesterone ADT Androgen deprivation therapy ANOVA Analysis of variance AR Androgen Receptor AKR Aldo-Keto Reductase ATCC American Type Culture Collection CAM Cell Adhesion Molecule CYP Cytochrome P450 CBR1 Carbonyl reductase 1 CRPC Castration resistant prostate cancer Ct-value Cycle threshold-value DHRS7 (B/C) Dehydrogenase/Reductase Short Chain Dehydrogenase Family Member 7 (B/C) DHEA Dehydroepiandrosterone DHP Dehydroprogesterone DHT 5α-Dihydrotestosterone DMEM Dulbecco's Modified Eagle's Medium DMSO Dimethyl Sulfoxide DTT Dithiothreitol E1 Estrone E2 Estradiol ECM Extracellular Membrane EDTA Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid EMT Epithelial-mesenchymal transition ER Endoplasmic Reticulum ERα/β Estrogen Receptor α/β FBS Fetal Bovine Serum 3 FDR False discovery rate FGF Fibroblast growth factor HEPES 4-(2-Hydroxyethyl)-1-Piperazineethanesulfonic Acid HMDB Human Metabolome Database HPLC High Performance Liquid Chromatography HSD Hydroxysteroid Dehydrogenase IC50 Half-Maximal Inhibitory Concentration LNCaP Lymph node carcinoma of the prostate mRNA Messenger Ribonucleic Acid n.d. -

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Materials COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS OF THE TRANSCRIPTOME, PROTEOME AND miRNA PROFILE OF KUPFFER CELLS AND MONOCYTES Andrey Elchaninov1,3*, Anastasiya Lokhonina1,3, Maria Nikitina2, Polina Vishnyakova1,3, Andrey Makarov1, Irina Arutyunyan1, Anastasiya Poltavets1, Evgeniya Kananykhina2, Sergey Kovalchuk4, Evgeny Karpulevich5,6, Galina Bolshakova2, Gennady Sukhikh1, Timur Fatkhudinov2,3 1 Laboratory of Regenerative Medicine, National Medical Research Center for Obstetrics, Gynecology and Perinatology Named after Academician V.I. Kulakov of Ministry of Healthcare of Russian Federation, Moscow, Russia 2 Laboratory of Growth and Development, Scientific Research Institute of Human Morphology, Moscow, Russia 3 Histology Department, Medical Institute, Peoples' Friendship University of Russia, Moscow, Russia 4 Laboratory of Bioinformatic methods for Combinatorial Chemistry and Biology, Shemyakin-Ovchinnikov Institute of Bioorganic Chemistry of the Russian Academy of Sciences, Moscow, Russia 5 Information Systems Department, Ivannikov Institute for System Programming of the Russian Academy of Sciences, Moscow, Russia 6 Genome Engineering Laboratory, Moscow Institute of Physics and Technology, Dolgoprudny, Moscow Region, Russia Figure S1. Flow cytometry analysis of unsorted blood sample. Representative forward, side scattering and histogram are shown. The proportions of negative cells were determined in relation to the isotype controls. The percentages of positive cells are indicated. The blue curve corresponds to the isotype control. Figure S2. Flow cytometry analysis of unsorted liver stromal cells. Representative forward, side scattering and histogram are shown. The proportions of negative cells were determined in relation to the isotype controls. The percentages of positive cells are indicated. The blue curve corresponds to the isotype control. Figure S3. MiRNAs expression analysis in monocytes and Kupffer cells. Full-length of heatmaps are presented. -

A Brief Guide to Enzyme Classification and Nomenclature Rev AM

A Brief Guide to Enzyme Nomenclature and Classification Keith Tipton and Andrew McDonald 1) Introduction NC-IUBMB Enzyme List, or, to give it its full title, “Recommendations of the Nomenclature Committee of the International Union of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology on the Nomenclature and Classification of Enzymes by the Reactions they Catalyse,1 is a functional system, based solely on the substrates transformed and products formed by an enzyme. The basic layout of the classification for each enzyme is described below with some indication of the guidelines followed. More detailed rules for enzyme nomenclature and classification are available online.2 Further details of the principles governing the nomenclature of individual enzyme classes are given in the following sections. 2. Basic Concepts 2.1. EC numbers Enzymes are identified by EC (Enzyme Commission) numbers. These are also valuable for relating the information to other databases. They were divided into 6 major classes according to the type of reaction catalysed and a seventh, the translocases, was added in 2018.3 These are shown in Table 1. Table 1. Enzyme classes Name Reaction catalysed 1 Oxidoreductases *AH2 + B = A +BH2 2 Transferases AX + B = BX + A 3 Hydrolases A-B + H2O = AH + BOH 4 Lyases A=B + X-Y = A-B ç ç X Y 5 Isomerases A = B 6 LiGases †A + B + NTP = A-B + NDP + P (or NMP + PP) 7 Translocases AX + B çç = A + X + ççB (side 1) (side 2) *Where nicotinamide-adenine dinucleotides are the acceptors, NAD+ and NADH + H+ are used, by convention. †NTP = nucleoside triphosphate. The EC number is made up of four components separated by full stops. -

The Role of Alcohol Dehydrogenase Genes in the Development of Fetal

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Wits Institutional Repository on DSPACE The Role of Alcohol Dehydrogenase Genes in the Development of Fetal Alcohol Syndrome in Two South African Coloured Communities Dhamari Naidoo Division of Human Genetics National Health Laboratory Service and, School of Pathology, University of Witwatersrand Johannesburg South African A dissertation submitted in the Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Witwatersrand, in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Masters of Science in Medicine. i Declaration I, Dhamari Naidoo, hereby declare that this is my own unaided work, unless otherwise stated. The statistical analyses were either checked by a statistician or, in the case of the logistic regression analysis, haplotype inference and linkage disequilibrium calculations, performed by a statistician with detailed consultation. It is being submitted for the degree of Masters in Medical Science in Human Genetics at the University of Witwatersrand. It has not been submitted for any other degree at any other university. ……………………….. ………………………….. Dhamari Naidoo Date Bsc(Hons) ii Acknowledgements Prof. Michele Ramsay for all the help, guidance and most importantly your patience throughout my project Dr Lize van der Merwe for all the much appreciated help with the statistical analysis Lillian Ouko, Zane Lombard, Shelley Macauley, Phillip Haycock and Desmond Schnugh, thank you for your friendship and for making my time spent on this project an enjoyable one Thank you to all my -

Evolution of 17Beta-Hydroxysteroid Dehydrogenases and Their Role in Androgen, Estrogen and Retinoid Action

UC San Diego UC San Diego Previously Published Works Title Evolution of 17beta-Hydroxysteroid Dehydrogenases and Their Role in Androgen, Estrogen and Retinoid Action Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/1md640v5 Journal Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology, 171 Author Baker, Michael E Publication Date 2001 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Molec ular and Cellular Endocrinol ogy vol. 171, pp. 211 -215, 2001. Evolution of 17 -Hydroxysteroid Dehydrogenases and Their Role in Androgen, Estrogen and Retinoid Action Michael E. Baker Department of Medicine, 0823 University of California, San Diego 950 0 Gilman Drive La Jolla, CA 92093 -0823 phone: 858 -534 -8317 fax: 858 -822 -0873 e-mail: [email protected] Abstract. 17 -hydroxysteroid dehydrogenases (17 -HSDs) regulate androgen and estrogen concentrations in mammals. By 1995, four distinct enzymes with 17 -HSD activity had been identified: 17 -HSD -types 1 and 3, which in vivo are NADPH -dependent reductases; 17 -HSD - types 2 and 4, which in vivo are NAD +-dependent oxidases. Since then six additional enzymes with 17 -HSD activity have been isolated from mammal s. With the exception of 17 -HSD –type 5, which belongs to the aldoketo -reductase (AKR) family, these 17 -HSDs belong to the short chain dehydrogenases/reductases (SDR) family. Several 17 -HSDs appear to be examples of convergent evolution. That is, 17 -HSD activity arose several times from different ancestors. Some 17 -HSDs share a common ancestor with retinoid oxido -reductases and have retinol dehydrogenase activity. 17 -HSD -types 2, 6 and 9 appear to have diverged from ancestral retinoid dehydrogenas es early in the evolution of deuterostomes during the Cambrian, about 540 million years ago. -

SELENOF) with Retinol Dehydrogenase 11 (RDH11

Tian et al. Nutrition & Metabolism (2018) 15:7 DOI 10.1186/s12986-017-0235-x RESEARCH Open Access The interaction of selenoprotein F (SELENOF) with retinol dehydrogenase 11 (RDH11) implied a role of SELENOF in vitamin A metabolism Jing Tian1* , Jiapan Liu1, Jieqiong Li2, Jingxin Zheng3, Lifang Chen4, Yujuan Wang1, Qiong Liu1 and Jiazuan Ni1 Abstract Background: Selenoprotein F (SELENOF, was named as 15-kDa selenoprotein) has been reported to play important roles in oxidative stress, endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress and carcinogenesis. However, the biological function of SELENOF is still unclear. Methods: A yeast two-hybrid system was used to screen the interactive protein of SELENOF in a human fetal brain cDNA library. The interaction between SELENOF and interactive protein was validated by fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET), co-immunoprecipitation (co-IP) and pull-down assays. The production of retinol was detected by high performance liquid chromatograph (HPLC). Results: Retinol dehydrogenase 11 (RDH11) was found to interact with SELENOF. RDH11 is an enzyme for the reduction of all-trans-retinaldehyde to all-trans-retinol (vitamin A). The production of retinol was decreased by SELENOF overexpression, resulting in more retinaldehyde. Conclusions: SELENOF interacts with RDH11 and blocks its enzyme activity to reduce all-trans-retinaldehyde. Keywords: SELENOF (Seleonoprotein F) , Yeast two hybrid system, Protein-protein interaction, Retinol dehydrogenase 11 (RDH11), Fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET), Co-immunoprecipitation (co-IP), Pull- down, Retinol (vitamin a), Retinaldehyde Background SELENOF shows that the protein contains a Selenium (Se) is a necessary trace element for human thioredoxin-like motif. The redox potential of this motif health. -

Pyruvate Ferredoxin Oxidoreductase from the Hyperthermophilic

Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA Vol. 94, pp. 9608–9613, September 1997 Biochemistry Pyruvate ferredoxin oxidoreductase from the hyperthermophilic archaeon, Pyrococcus furiosus, functions as a CoA-dependent pyruvate decarboxylase (archaeayaldehydeydecarboxylationy2-keto acidythiamine pyrophosphate) KESEN MA*, ANDREA HUTCHINS*, SHI-JEAN S. SUNG†, AND MICHAEL W. W. ADAMS*‡ *Center for Metalloenzyme Studies, Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, University of Georgia, Athens, GA 30602; and †Institute of Tree Root Biology, U.S. Department of Agriculture–Forest Service, Athens, GA 30602 Communicated by Gregory A. Petsko, Brandeis University, Waltham, MA, June 17, 1997 (received for review June 1, 1996) ABSTRACT Pyruvate ferredoxin oxidoreductase (POR) hyperthermophilic archaea and these are involved in peptide has been previously purified from the hyperthermophilic fermentation. They use 2-ketoglutarate (KGOR) (11), in- archaeon, Pyrococcus furiosus, an organism that grows opti- dolepyruvate (IOR) (12), and 2-ketoisovalerate (VOR) (13) as mally at 100°C by fermenting carbohydrates and peptides. The substrates, and function to oxidatively decarboxylate the 2- enzyme contains thiamine pyrophosphate and catalyzes the keto acids generated by the transamination of glutamate, oxidative decarboxylation of pyruvate to acetyl-CoA and CO2 aromatic amino acids, and branched chain amino acids, re- and reduces P. furiosus ferredoxin. Here we show that this spectively, to the corresponding CoA derivative (13). enzyme also catalyzes the formation of acetaldehyde from The growth of hyperthermophilic archaea such as P. furiosus pyruvate in a CoA-dependent reaction. Desulfocoenzyme A is also unusual in that it is dependent upon tungsten (14), a substituted for CoA showing that the cofactor plays a struc- metal seldom used in biological systems (15). -

A Nitrogenase-Like Methylthio-Alkane Reductase Complex Catalyzes Anaerobic Methane, Ethylene, and Methionine Biosynthesis Justin A

A Nitrogenase-like Methylthio-alkane Reductase Complex Catalyzes Anaerobic Methane, Ethylene, and Methionine Biosynthesis Justin A. North,1 Srividya Murali1* ([email protected]), Adrienne B. Narrowe,3 Weili Xiong,4 Kathryn M. Byerly,1 Sarah J. Young,1 Yasuo Yoshikuni,5 Sean McSweeney,6 Dale Kreitler,6 William R. Cannon,2 Kelly C. Wrighton,3 Robert L. Hettich,4 and F. Robert Tabita1 (former PI, deceased) 1Department of Microbiology, The Ohio State University, Columbus, OH; 2Pacific Northwest National Laboratory, Richland, WA. 3Department of Soil and Crop Sciences, Colorado State University, Fort Collins, CO; 4Chemical Sciences Division, ORNL, Oak Ridge, TN; 5DOE Joint Genome Institute, Berkeley, CA; 6NSLS-II, Brookhaven National Laboratory, Upton, NY. Project Goals: The goal of this project is to identify and characterize the specific enzyme(s) that catalyze anaerobic ethylene synthesis. This is part of a larger project to develop an industrially compatible microbial process to synthesize ethylene in high yields. The specific goals are: 1. Identify the genes and gene products responsible for anaerobic ethylene synthesis. 2. Probe the substrate specificity and metagenomic functional diversity of methylthio-alkane reductases to identify optimal bioproduct generating systems. 3. Characterize the enzymes and the reactions that directly generate anaerobic ethylene. Abstract Text: Our previous work identified a novel anaerobic microbial pathway (DHAP- Ethylene Shunt) [1] that recycled 5’-methylthioadenosine (MTA) back to methionine with stoichiometric amounts of ethylene produced as a surprising side-product. MTA is a metabolic byproduct of methionine utilization in a multitude of cellular processes. The initial steps of the DHAP-ethylene sequentially converts MTA to dihydroxyacetone phosphate (DHAP) and ethylene precursor (2-methylthio)ethanol (Fig. -

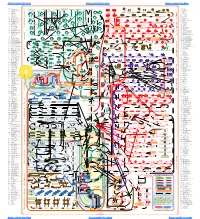

O O2 Enzymes Available from Sigma Enzymes Available from Sigma

COO 2.7.1.15 Ribokinase OXIDOREDUCTASES CONH2 COO 2.7.1.16 Ribulokinase 1.1.1.1 Alcohol dehydrogenase BLOOD GROUP + O O + O O 1.1.1.3 Homoserine dehydrogenase HYALURONIC ACID DERMATAN ALGINATES O-ANTIGENS STARCH GLYCOGEN CH COO N COO 2.7.1.17 Xylulokinase P GLYCOPROTEINS SUBSTANCES 2 OH N + COO 1.1.1.8 Glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase Ribose -O - P - O - P - O- Adenosine(P) Ribose - O - P - O - P - O -Adenosine NICOTINATE 2.7.1.19 Phosphoribulokinase GANGLIOSIDES PEPTIDO- CH OH CH OH N 1 + COO 1.1.1.9 D-Xylulose reductase 2 2 NH .2.1 2.7.1.24 Dephospho-CoA kinase O CHITIN CHONDROITIN PECTIN INULIN CELLULOSE O O NH O O O O Ribose- P 2.4 N N RP 1.1.1.10 l-Xylulose reductase MUCINS GLYCAN 6.3.5.1 2.7.7.18 2.7.1.25 Adenylylsulfate kinase CH2OH HO Indoleacetate Indoxyl + 1.1.1.14 l-Iditol dehydrogenase L O O O Desamino-NAD Nicotinate- Quinolinate- A 2.7.1.28 Triokinase O O 1.1.1.132 HO (Auxin) NAD(P) 6.3.1.5 2.4.2.19 1.1.1.19 Glucuronate reductase CHOH - 2.4.1.68 CH3 OH OH OH nucleotide 2.7.1.30 Glycerol kinase Y - COO nucleotide 2.7.1.31 Glycerate kinase 1.1.1.21 Aldehyde reductase AcNH CHOH COO 6.3.2.7-10 2.4.1.69 O 1.2.3.7 2.4.2.19 R OPPT OH OH + 1.1.1.22 UDPglucose dehydrogenase 2.4.99.7 HO O OPPU HO 2.7.1.32 Choline kinase S CH2OH 6.3.2.13 OH OPPU CH HO CH2CH(NH3)COO HO CH CH NH HO CH2CH2NHCOCH3 CH O CH CH NHCOCH COO 1.1.1.23 Histidinol dehydrogenase OPC 2.4.1.17 3 2.4.1.29 CH CHO 2 2 2 3 2 2 3 O 2.7.1.33 Pantothenate kinase CH3CH NHAC OH OH OH LACTOSE 2 COO 1.1.1.25 Shikimate dehydrogenase A HO HO OPPG CH OH 2.7.1.34 Pantetheine kinase UDP- TDP-Rhamnose 2 NH NH NH NH N M 2.7.1.36 Mevalonate kinase 1.1.1.27 Lactate dehydrogenase HO COO- GDP- 2.4.1.21 O NH NH 4.1.1.28 2.3.1.5 2.1.1.4 1.1.1.29 Glycerate dehydrogenase C UDP-N-Ac-Muramate Iduronate OH 2.4.1.1 2.4.1.11 HO 5-Hydroxy- 5-Hydroxytryptamine N-Acetyl-serotonin N-Acetyl-5-O-methyl-serotonin Quinolinate 2.7.1.39 Homoserine kinase Mannuronate CH3 etc. -

RDH5 Gene Retinol Dehydrogenase 5

RDH5 gene retinol dehydrogenase 5 Normal Function The RDH5 gene provides instructions for making an enzyme called 11-cis retinol dehydrogenase 5, which is necessary for normal vision, especially in low-light conditions (night vision). This enzyme is found in a thin layer of cells at the back of the eye called the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE). This cell layer supports and nourishes the retina, which is the light-sensitive tissue in the inner lining of the back of the eye (the fundus). 11-cis retinol dehydrogenase 5 is involved in a multi-step process called the visual cycle, by which light entering the eye is converted into electrical signals that are interpreted as vision. An integral operation of the visual cycle is the recycling of a molecule called 11- cis retinal, which is a form of vitamin A that is needed for the conversion of light to electrical signals. The retinol dehydrogenase 5 enzyme converts a molecule called 11- cis retinol to 11-cis retinal. In light-sensing cells in the retina known as photoreceptors, 11-cis retinal combines with a protein called an opsin to form a photosensitive pigment. When light hits this pigment, 11-cis retinal is altered, forming another molecule called all- trans retinal. This conversion triggers a series of chemical reactions that create electrical signals. 11-cis retinol dehydrogenase 5 then helps convert all-trans retinal back to 11-cis retinal so the visual cycle can begin again. The eyes contain two types of photoreceptors, rods and cones. Rods are needed for vision in low light, while cones are needed for vision in bright light, including color vision. -

Methylenetetrahydrofolate Reductase: a Common Human Polymorphism and Its Biochemical Implications

THE CHEMICAL RECORD Methylenetetrahydrofolate Reductase: THE CHEMICAL A Common Human Polymorphism and RECORD Its Biochemical Implications ROWENA G. MATTHEWS1,2 1Biophysics Research Division, The University of Michigan, 930 N. University Avenue, Ann Arbor, Michigan 48109-1055 2Department of Biological Chemistry, The University of Michigan, 930 N. University Avenue, Ann Arbor, Michigan 48109-1055 Received 6 June 2001; accepted 7 September 2001 ABSTRACT: Methlenetetrahydrofolate (CH2-H4folate) is required for the conversion of homocys- teine to methionine and of dUMP to dTMP in support of DNA synthesis, and also serves as a major source of one carbon unit for purine biosynthesis. This review presents biochemical studies of a human polymorphism in methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase, which catalyzes the reaction shown below. The mutation decreases the flux of CH2-H4folate into CH3-H4folate, and is associated with both beneficial and deleterious effects that can be traced to the molecular effect of the substitution of alanine 222 by valine. © 2002 The Japan Chemical Journal Forum and John Wiley & Sons, Inc. Chem Rec 2: 4–12, 2002 Key words: flavoprotein; homocysteine; methionine Introduction One of the more remarkable chemical syntheses carried out by transferase, as shown in Equation 1. Alternate sources of the biological organisms is the de novo biosynthesis of methyl methylene group include formate, which is converted to 10- groups. Du Vigneaud and Bennett are credited with the initial formyltetrahydrofolate, and thence to methenyl- and finally observations that rats could synthesize methionine from ho- methylenetetrahydrofolate by the action of formyltetra- mocysteine in the absence of a source of preformed methyl hydrofolate synthetase, methenyltetrahydrofolate cyclohydro- groups, and this synthesis was later shown to require the pres- lase, and methylenetetrahydrofolate dehydrogenase.2 ence of folate and cobalamin in the diet.